Ezra Pound / Henri Michaux): Two Poetics of the Ideogram1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC 1 Dear Candidate, in Preparation for the Graphic Design & Illu

Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC Dear Candidate, In preparation for the Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC certification exam, we’ve put together a set of practice materials and example exam items for you to review. What you’ll find in this packet are: • Topic areas and objectives for the exam. • Links to practice tutorials and files. • Practice exam items. We’ve assembled excerpted material from the Adobe Illustrator CC Learn and Support page, and the Visual Design curriculum to highlight a few of the more challenging techniques covered on the exam. You can work through these technical guides and with the provided image files (provided separately). Additionally, we’ve included the certification objectives so that you are aware of the elements that are covered on the exam. Finally, we’ve included practice exam items to give you a feel for some of the items. These materials are meant to help you familiarize yourself with the areas of the exam so are not comprehensive across all the objectives. Thank you, Adobe Education Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Photoshop and Creative Cloud are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems 1 Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. © 2017 Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC Adobe Certified Associate in Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC (2015) Exam Structure The following lists the topic areas for the exam: • Setting project requirements • Understanding Digital Graphics and Illustrations • Understanding Adobe Illustrator • Creating Digital Graphics and Illustrations Using Adobe Illustrator • Archive, Export, and Publish Graphics Using Adobe Illustrator Number of Questions and Time • 40 questions • 50 minutes Exam Objectives Domain 1.0 Setting Project Requirements 1.1 Identify the purpose, audience, and audience needs for preparing graphics and illustrations. -

617.727.5944 2.7 Labeling a Picture Or a Diagram

BPS Curriculum Framework > Informational/Explanatory Text > Grade 2 > Drafting and Revising > Labeling a picture or diagram 2.7 Labeling a picture or a Connection : We have been noticing the beautiful pictures and helpful diagram diagrams in our mentor text for “all-about” books. We have even added pictures and diagrams to our own writing to really give our readers a better idea of what our subject looks like, but there is still one more thing we need to think about. We need to be sure our readers understand what they are looking at. Learning Objective: Students will label pictures and Teaching : Labeling our pictures gives our readers a better diagrams from the outdoor understanding of what they are looking at. Our labels help the reader classroom know exactly what they are seeing. It may tell the time of the year, the location, the size, or the specific parts of the subject they are looking at. Let’s look at The “Saddle Up!” Section in the “Kids book of Horses” and see how the author has used labels to teach us the parts of a Mentor Texts: “Volcanoes”; saddle. “Bears, Bears, Bears”; “Try It Think about something in the classroom and tell your partner “Apples”; “The Pumpkin what you might have to label if you were going to illustrate this object. Book”; “ The Kids Horse Book ”, Share out with class. Sylvia Funston Instructions to students for Independent Outdoor Writing : 1. Today, when we go out to the outdoor classroom we are going to choose an object to illustrate. It can be from our classroom list or anything else you see outside (at boat in the harbor, a truck or car going by, a small animal scampering away, or items on the playground: a slide or climbing frame. -

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

The Thought of What America": Ezra Pound’S Strange Optimism

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO English Faculty Publications Department of English and Foreign Languages 2010 "The Thought of What America": Ezra Pound’s Strange Optimism John Gery University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/engl_facpubs Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Gery, John “‘The Thought of What America’: Ezra Pound’s Strange Optimism,” Belgrade English Language and Literature Studies, Vol. II (2010): 187-206. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English and Foreign Languages at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UDC 821.111(73).09-1 Pand E. John R O Gery University of New Orleans, USA “THE THOUGHT OF What AMerica”: EZRA POUND’S STRANGE OPTIMISM Abstract Through a reconsideration of Ezra Pound’s early poem “Cantico del Sole” (1918), an apparently satiric look at American culture in the early twentieth century, this essay argues how the poem, in fact, expresses some of the tenets of Pound’s more radical hopes for American culture, both in his unorthodox critiques of the 1930s in ABC of Reading, Jefferson and/or Mussolini, and Guide to Kulchur and, more significantly, in his epic poem, The Cantos. The essay contends that, despite Pound’s controversial economic and political views in his prose (positions which contributed to his arrest for treason in 1945), he is characteristically optimistic about the potential for American culture. -

Guns, More Crime Author(S): Mark Duggan Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol

More Guns, More Crime Author(s): Mark Duggan Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 109, No. 5 (October 2001), pp. 1086-1114 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/322833 Accessed: 03-04-2018 19:37 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Political Economy This content downloaded from 153.90.149.52 on Tue, 03 Apr 2018 19:37:56 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms More Guns, More Crime Mark Duggan University of Chicago and National Bureau of Economic Research This paper examines the relationship between gun ownership and crime. Previous research has suffered from a lack of reliable data on gun ownership. I exploit a unique data set to reliably estimate annual rates of gun ownership at both the state and the county levels during the past two decades. My findings demonstrate that changes in gun ownership are significantly positively related to changes in the hom- icide rate, with this relationship driven almost entirely by an impact of gun ownership on murders in which a gun is used. -

Graphics Formats and Tools

Graphics formats and tools Images à recevoir Stand DRG The different types of graphics format Graphics formats can be classified broadly in 3 different groups -Vector - Raster (or bitmap) - Page description language (PDL) Graphics formats and tools 2 Vector formats In a vector format (revisable) a line is defined by 2 points, the text can be edited Graphics formats and tools 3 Raster (bitmap) format A raster (bitmap) format is like a photograph; the number of dots/cm defines the quality of the drawing Graphics formats and tools 4 Page description language (PDL) formats A page description language is a programming language that describes the appearance of a printed page at a higher level than an actual output bitmap Adobe’s PostScript (.ps), Encapsulated PostScript (.eps) and Portable Document Format (.pdf) are some of the best known page description languages Encapsulated PostScript (.eps) is commonly used for graphics It can contain both unstructured vector information as well as raster (bitmap) data Since it comprises a mixture of data, its quality and usability are variable Graphics formats and tools 5 Background Since the invention of computing, or more precisely since the creation of computer-assisted drawing (CAD), two main professions have evolved - Desktop publishing (DTP) developed principally on Macintosh - Computer-assisted drawing or design (CAD) developed principally on IBM (International Business Machines) Graphics formats and tools 6 Use of DTP applications Used greatly in the fields of marketing, journalism and industrial design, DTP applications fulfil the needs of various professions - from sketches and mock-ups to fashion design - interior design - coachwork (body work) design - web page design -etc. -

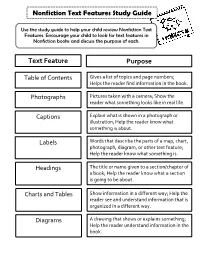

Nonfiction Text Features Study Guide Text Feature Purpose

Nonfiction Text Features Study Guide Use the study guide to help your child review Nonfiction Text Features. Encourage your child to look for text features in Nonfiction books and discuss the purpose of each. Text Feature Purpose Gives a list of topics and page numbers; Table of Contents Helps the reader find information in the book. Photographs Pictures taken with a camera; Show the reader what something looks like in real life. Captions Explain what is shown in a photograph or illustration; Help the reader know what something is about. Labels Words that describe the parts of a map, chart, photograph, diagram, or other text feature; Help the reader know what something is. Headings The title or name given to a section/chapter of a book; Help the reader know what a section is going to be about. Charts and Tables Show information in a different way; Help the reader see and understand information that is organized in a different way. Diagrams A drawing that shows or explains something; Help the reader understand information in the book. Text Feature Purpose Textboxes A box or some other shape that contains text; Show the reader that information is important or interesting. A picture of what something looks like on the Cutaways inside or from another point of view; Help the reader see all parts of something. Types of Print Print can be bold, different colors, fonts, and sizes; Show the reader that something is important or interesting. Close Ups Photographs that have been zoomed in or enlarged to help the reader see something better. -

Illustration Degree Offered: Bachelor of Fine Arts

Illustration Degree Offered: Bachelor of Fine Arts Minors Offered: • Art • Art History • Graphic Design • Illustration • Painting • Sculpture • Theatre Arts The BFA in Illustration focuses on developing drawing skills and their application in a professional en vironment, including editorial illustration, children's book illustration, web-site development, and character design for animation. Illustration at Daemen: • Demonstrate a high level of accomplishment with materials related to the graphic arts. • Visually present a narrative voice through individual compositions or series. • Work within a variety of media to explore editorial or sequential imagery. • Develop an editorial voice to support campaigns, storylines, or public initiatives. Illustration Emphasis: The BFA in Illustration at Daemen College combines the creative process of a fine artist with the problem solving techniques and communication skills of a commercial designer. Students are taught to brainstorm solutions, generate new ideas, and explore the materials and techniques best suited to present an idea. By graduation, the Illustration student will have ex perience in editorial, sequential, computer, packaging and storyboard illustration. Illustration studio courses are supported by substantive drawing instruction, as well as fundamental graphic design con cepts. The program's focus on exploration and process prepares students to develop a portfolio to successfully acquire freelance illustration work, or a full-time position in the publishing or digital communications industry. Faculty: The Illustration faculty work in a variety of professional situations by providing illustrations to magazines, poster cam paigns, and websites. Each maintains a freelance career while simultaneously working with students at Daemen in the development of projects and exhibits. 4103 Suggested Course Sequence for Illustration: 4897 10/16 For more information, contact Christian Brandjes in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at [email protected] or 716-839-8463. -

Ellie Rastian Product Designer 017675131412

[email protected] Ellie Rastian www.65ping.studio Product Designer 017675131412 Experience Certification dunnhumby Germany GmbH Nielsen Norman Group 2018 March - 2020 July (2019) Berlin, Germany UX Certified Web designer Starting as a visual designer, I worked on e- Scrum.org commerce projects related to European Market. (2020) Soon, I showed my skills as a UX/UI designer and Professional Scrum Master was assigned to design the internal website for the Creative Services Team. I worked with the UX team and CS team to develop the website. University of Minnesota coursera Saatchi & Saatchi (2018 - 2019) 2015 March - 2016 June User Interface Design Specialization Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Visual Designer Involved in ideation and execution for ATL & BTL Education advertising campaigns, proposals and pitches. Clients: MINI Malaysia, Bank Simpanan Nasional Malaysian Institute of Art (BSN). (2014 - 2016) Graphic Design Freelancer 2014 July - Present Shiraz University Visual Designer, UX Designer, Illustrator (2008 - 2010) I have spent over seven years crafting and delivering Bachelor of Business Administration unique digital experiences for global companies and BBA, Accounting and Finance startups such as MINI, Sam Media, Elixir Berlin Khalij Fars Online Language 2008 April - 2010 September Booshehr, Iran English Full professional proficiency Limited working proficiency, B1 Financial Accountant German Persian Full professional proficiency Malay Elementary proficiency Skills Design Tools Interaction Design, Visual Design, Information Sketch, InVision, -

Methodology for Producing a Hand-Drawn Thematic City Map

Master Thesis Methodology for Producing a Hand-Drawn Thematic City Map submitted by: Alika C. Jensen born on: 27.08.1992 in Dayton, Ohio, USA submitted for the academic degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) Date of Submission 16.10.2017 Supervisors Prof. Dipl.-Phys. Dr.-Ing. habil. Dirk Burghardt Technische Universität Dresden Univ.Prof. Mag.rer.nat. Dr.rer.nat. Georg Gartner Technische Universität Wien Statement of Authorship Herewith I declare that I am the sole author of the thesis named „Methodology for Producing a Hand-Drawn Thematic City Map“ which has been submitted to the study commission of geosciences today. I have fully referenced the ideas and work of others, whether published or unpublished. Literal or analogous citations are clearly marked as such. Dresden, 16.10.2017 Signature Alika C. Jensen 2 Contents Title............................................................................................................................................1 Statement of Authorship...........................................................................................................2 Contents....................................................................................................................................3 Figures.......................................................................................................................................5 Terminology..............................................................................................................................7 1 Introduction...........................................................................................................................8 -

Ezra Pound's Imagist Theory and T .S . Eliot's Objective Correlative

Ezra Pound’s Imagist theory and T .S . Eliot’s objective correlative JESSICA MASTERS Abstract Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot were friends and collaborators. The effect of this on their work shows similar ideas and methodological beliefs regarding theory and formal technique usage, though analyses of both theories in tandem are few and far between. This essay explores the parallels between Pound’s Imagist theory and ideogrammic methods and Eliot’s objective correlative as outlined in his 1921 essay, ‘Hamlet and His Problems’, and their similar intellectual debt to Walter Pater and his ‘cult of the moment’. Eliot’s epic poem, ‘The Waste Land’ (1922) does not at first appear to have any relationship with Pound’s Imagist theory, though Pound edited it extensively. Further investigation, however, finds the same kind of ideogrammic methods in ‘The Waste Land’ as used extensively in Pound’s Imagist poetry, showing that Eliot has intellectual Imagist heritage, which in turn encouraged his development of the objective correlative. The ultimate conclusion from this essay is that Pound and Eliot’s friendship and close proximity encouraged a similarity in their theories that has not been fully explored in the current literature. Introduction Eliot’s Waste Land is I think the justification of the ‘movement,’ of our modern experiment, since 1900 —Ezra Pound, 1971 Ezra Pound (1885–1972) and Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) were not only poetic contemporaries but also friends and collaborators. Pound was the instigator of modernism’s first literary movement, Imagism, which centred on the idea of the one-image poem. A benefit of Pound’s theoretically divisive Imagist movement was that it prepared literary society to welcome the work of later modernist poets such as Eliot, who regularly used Imagist techniques such as concise composition, parataxis and musical rhythms to make his poetry, specifically ‘The Waste Land’ (1922), decidedly ‘modern’. -

GDT239. Imaging and Illustration

Washtenaw Community College Comprehensive Report GDT 239 Imaging and Illustration Effective Term: Spring/Summer 2016 Course Cover Division: Business and Computer Technologies Department: Digital Media Arts Discipline: Graphic Design Technology Course Number: 239 Org Number: 14500 Full Course Title: Imaging and Illustration Transcript Title: Imaging and Illustration Is Consultation with other department(s) required: No Publish in the Following: College Catalog , Time Schedule , Web Page Reason for Submission: Course Change Change Information: Consultation with all departments affected by this course is required. Pre-requisite, co-requisite, or enrollment restrictions Outcomes/Assessment Rationale: Adding back in to the program after removal from restricted elective. Proposed Start Semester: Spring/Summer 2016 Course Description: In this course, the student develops skills with advanced digital tools, methodologies and concepts for communicating visual solutions with real world relevance. A variety of projects may include information graphics, rendering, editorial and interpretive illustration, spot illustration and promotional illustration. Course Credit Hours Variable hours: No Credits: 4 Lecture Hours: Instructor: 45 Student: 45 Lab: Instructor: 0 Student: 0 Clinical: Instructor: 0 Student: 0 Other: Instructor: 45 Student: 45 Total Contact Hours: Instructor: 90 Student: 90 Repeatable for Credit: NO Grading Methods: Letter Grades Audit Are lectures, labs, or clinicals offered as separate sections?: NO (same sections) College-Level Reading and Writing College-level Reading & Writing College-Level Math Requisites Prerequisite GDT 112 and Prerequisite GDT 104 minimum grade "C+" http://www.curricunet.com/washtenaw/reports/course_outline_HTML.cfm?courses_id=9364[2/9/2016 2:40:25 PM] General Education General Education Area 7 - Computer and Information Literacy Assoc in Arts - Comp Lit Assoc in Applied Sci - Comp Lit Assoc in Science - Comp Lit Request Course Transfer Proposed For: Student Learning Outcomes 1.