Taylor at EABH Prague 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Musical Imaginary, Identity and Representation: the Case of Gentleman the German Reggae Luminary

Ali 1 Musical Imaginary, Identity and Representation: The Case of Gentleman the German Reggae Luminary A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with distinction in Comparative Studies in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University By Raghe Ali April 2013 The Ohio State University Project Advisors Professor Barry Shank, Department of Comparative Studies Professor Theresa Delgadillo, Department of Comparative Studies Ali 2 In 2003 a German reggae artist named Gentleman was scheduled to perform at the Jamworld Entertainment Center in the south eastern parish of St Catherine, Jamaica. The performance was held at the Sting Festival an annual reggae event that dates back some twenty years. Considered the world’s largest one day reggae festival, the event annually boasts an electric atmosphere full of star studded lineups and throngs of hardcore fans. The concert is also notorious for the aggressive DJ clashes1 and violent incidents that occur. The event was Gentleman’s debut performance before a Jamaican audience. Considered a relatively new artist, Gentleman was not the headlining act and was slotted to perform after a number of familiar artists who had already “hyped” the audience with popular dancehall2 reggae hits. When his turn came he performed a classical roots 3reggae song “Dem Gone” from his 2002 Journey to Jah album. Unhappy with his performance the crowd booed and jeered at him. He did not respond to the heckling and continued performing despite the audience vocal objections. Empty beer bottles and trash were thrown onstage. Finally, unable to withstand the wrath and hostility of the audience he left the stage. -

Nazi Germany and the Jews Ch 3.Pdf

AND THE o/ w VOLUME I The Years of Persecution, i933~i939 SAUL FRIEDLANDER HarperCollinsPííMí^ers 72 • THE YEARS OF PERSECUTION, 1933-1939 dependent upon a specific initial conception and a visible direction. Such a CHAPTER 3 conception can be right or wrong; it is the starting point for the attitude to be taken toward all manifestations and occurrences of life and thereby a compelling and obligatory rule for all action."'^'In other words a worldview as defined by Hitler was a quasi-religious framework encompassing imme Redemptive Anti-Semitism diate political goals. Nazism was no mere ideological discourse; it was a political religion commanding the total commitment owed to a religious faith."® The "visible direction" of a worldview implied the existence of "final goals" that, their general and hazy formulation notwithstanding, were sup posed to guide the elaboration and implementation of short-term plans. Before the fall of 1935 Hitler did not hint either in public or in private I what the final goal of his anti-Jewish policy might be. But much earlier, as On the afternoon of November 9,1918, Albert Ballin, the Jewish owner of a fledgling political agitator, he had defined the goal of a systematic anti- the Hamburg-Amerika shipping line, took his life. Germany had lost the Jewish policy in his notorious first pohtical text, the letter on the "Jewish war, and the Kaiser, who had befriended him and valued his advice, had question" addressed on September 16,1919, to one Adolf Gemlich. In the been compelled to abdicate and flee to Holland, while in Berlin a republic short term the Jews had to be deprived of their civil rights: "The final aim was proclaimed. -

Udr / Vertigo Berlin

UDR / VERTIGO BERLIN ::::: single “You Remember”, out April 5, 2013 album “New Day Dawn”, out April 19, 2013 GENTLEMAN - NEW DAY DAWN Let’s talk about personality. Let’s talk about splits. About love and responsibility. About doubt, gratitude and spirit. About change and new beginnings. Let’s talk about GENTLEMAN and his new album NEW DAY DAWN which will be out on April 19, 2013. It is the 38 year-old’s sixth studio album. Two decades ago, the Cologne-based artist first set foot on Jamaican soil and over the years he has been spreading reggae music all over the globe with his shows and is now an international reggae headliner. Over the past 20 years, the intensity of his vibes and his sincere and honest personality have earned him growing respect and the love of a global audience. He lives and shares with us his stories and his experiences. Undisguised and unpretentious. The album will come out as a standard and deluxe edition and with it GENTLEMAN invites us to join him for a “New Day Dawn”. It marks an impressive next step in the artist’s career and is the purest “Gentleman”-album that has ever been. For one, it is the first album that was created completely without collaborations or featured artists. And secondly, a lot of the ideas were developed and written by Gentleman himself. “I liked the idea of creating an album that would be purely Gentleman. There was no big plan behind it, it just sort of happened. I felt that “New Day Dawn” could work without featured artists. -

The Decision of Brexit and Its Impact on Germany and the European Union”

“The Decision of Brexit and its Impact on Germany and the European Union” Vice Minister, Dr. Günther Horzetzky Ladies and gentlemen, dear students, I am very pleased and honored to have the opportunity to speak to you in one of the oldest universities in Japan! Thank you very much for inviting me and for making this talk possible, dear Mr. Shinyo! You all should know: Originally I simply wanted to meet Mr. Shinyo, the former Japanese Ambassador to Germany, because • I always admire his tireless efforts to bring Germany and Japan together and • it always is rewarding – for Germans in particular - to ask for his views. But for today he had asked for my view on a phenomenon which is called BREXIT, i.e. the decision of the British electorate to opt out of the European Union. I am flattered. And I am nervous. But I will try my very best, Mr. Shinyo, to outline my assessment of this democratic decision of the British people and it’s possible repercussions on the EU, Germany and on North Rhine - Westphalia (NRW) in particular. In order to give you a clear, but also an emotional picture of what is at stake, I would like to start with my very personal experience with the European Union. In the 80s of the last century. It was a EU, far smaller than it is today. But still: A union of States. 1 And now European Policy becomes very personal for a minute. I was a young trade unionist, representing the farm workers union of West Germany. -

Freilandtheater Bad W Indsheim 2006

Nur heute Nacht, Eine Kriminaloper aus demer Franken der 20 Jahre von Christian MarleneLaubert Freilandtheater Bad Windsheim 2006 Visionen werden wahr Die konsequente Umsetzung von Visionen in Technik und De- sign hat MEKRA Lang zum Marktführer bei Rundumsichtsys- temen für Nutzfahrzeuge gemacht. Als Global Player sind wir weltweit zu Hause und übernehmen gleichzeitig Verantwor- tung am Standort Deutschland. Der stetige Ausbau des Fir- mensitzes in Ergersheim und des Verwaltungssitzes in Fürth sichert heute über 800 Arbeits- und Ausbildungsplätze vor Ort. Als erste Firma in der Region haben wir eine betriebseigene Kindertagesstätte aufgebaut, um die Vision einer echten Ver- einbarkeit von Beruf und Familie für unsere Mitarbeiter Wirk- lichkeit werden zu lassen. Auch das Theater im Freilandmuseum, hat mit einer Vision begonnen. Die Theatergruppe um das Pro- duktionsteam Falk, Laubert, Hägele bei der Verwirk- lichung dieser Idee zu unterstützen, ist uns auch in diesem Jahr wieder ein großes Anliegen. Theater wie es im Fränkischen Freilandmuseum dar- geboten wird, ist nicht allein Mittel der guten Unter- haltung, sondern Teil des kulturellen Gemeinschafts- lebens. Wir wünschen dem Theaterstück „Nur heute Nacht, Marlene“ eine erfolgreiche Saison und den Zuschauern unterhaltsame Stunden, in denen das Theater sie die Zeit vergessen lässt – unter frei- em Himmel und vor der wunderbaren Kulisse des Fränkischen Freilandmuseums. MEKRA Lang GmbH & Co. KG • Buchheimer Str. 4 • 91465 Ergersheim 3 Unsere Geschichte Zehn Jahre Demokratie Wir Franken! Wir sind ein Spiegel für gang Deutschland. Wir sind Bayern! Sind wir Bayern? Nun, ja und nein, möchte man da sagen: Nein! Denn unsere Herrschergeschlechter vor 1806 gehörten größtenteils zu den „Hohenzollern“, ein Name den man in Bayern Ende des ersten Weltkrieges besser nicht laut äußerte, war er doch gleichbedeutend mit Preußen, Bismarck und protestantisch wilhelminischem Zeitalter. -

View Complete Brochure

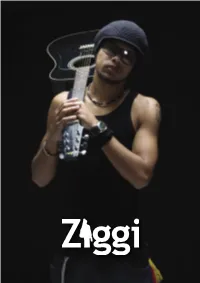

Contents Biography With his blazing performances on Summerjam Festival (Germany), Rototom Sun- splash (Italy), Two7Splash (Netherlands) and Zenith (France) just to mention a few, Holland’s #1 reggae artist Ziggi has put his permanent mark on the interna- tional reggae market. In September 2008 Ziggi will release his second album “In Transit”. On this album Ziggi proves that he’s an excellent singer, song writer. Artists such as Gentleman, Anthony B and Ce’Cile have collaborated with Ziggi on “In Transit”. From March 2008 Ziggi will start playing his new repertoire live throughout Europe and will start his album tour after the festival season. Ziggi’s Biography 3 Growing up on the Caribbean island of St. Eustatius the young Ricardo Blijden Press Picture 5 was given the nickname Ziggi by his grandparents who raised him. In 2001 Ziggi came to the Netherlands to study. It was in that time when he was introduced Fact Sheet 6 to Mr. Rude the owner of an independent studio and label called Rock’N Vibes Bookings and Contact information 7 Entertainment. Soon chilling out in the studio with friends became a professional musical career for Ziggi. Quote Mr Rude: “Ziggi had a vibe from the first time I heard him sing”. New album “In Transit” coming soon In February of 2006 Ziggi released his debut album So Much Reasons, with this album Ziggi managed to capture several awards in the Netherlands such as “Best Album”, “Best Artist” and “Best Live Act”. “So Much Reasons” produced several hits and had noticeable features on it with artists such as Elephant Man and Turbulence. -

Germans Settling North America : Going Dutch – Gone American

Gellinek Going Dutch – Gone American Christian Gellinek Going Dutch – Gone American Germans Settling North America Aschendorff Münster Printed with the kind support of Carl-Toepfer-Stiftung, Hamburg, Germany © 2003 Aschendorff Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Münster Das Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Die dadurch begründeten Rechte, insbesondere die der Überset- zung, des Nachdrucks, der Entnahme von Abbildungen, der Funksendung, der Wiedergabe auf foto- mechanischem oder ähnlichem Wege und der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlagen bleiben, auch bei nur auszugsweiser Verwertung, vorbehalten. Die Vergütungsansprüche des § 54, Abs. 2, UrhG, werden durch die Verwertungsgesellschaft Wort wahrgenommen. Druck: Druckhaus Aschendorff, Münster, 2003 Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier ∞ ISBN 3-402-05182-6 This Book is dedicated to my teacher of Comparative Anthropology at Yale Law School from 1961 to 1963 F. S. C. Northrop (1893–1992) Sterling Professor of Philosophy and Law, author of the benchmark for comparative philosophy, Philosophical Anthropology and Practical Politics This Book has two mottoes which bifurcate as the topic =s divining rod The first motto is by GERTRUDE STEIN [1874–1946], a Pennsylvania-born woman of letters, raised in California, and expatriate resident of Europe after 1903: AIn the United States there is more space where nobody is than where anybody is. That is what makes America what it is.@1 The second motto has to do with the German immigration. It is borrowed from a book by THEODOR FONTANE [1819–1898], a Brandenburg-born writer, and a critic of Prussia. An old German woman, whose grandchildren have emigrated to Anmerica is speaking in her dialect of Low German: [ADröwen in Amirika. -

An Introduction to the History of the Principal Kingdoms and States of Europe Natural Law and Enlightenment Classics

an introduction to the history of the principal kingdoms and states of europe natural law and enlightenment classics Knud Haakonssen General Editor Samuel Pufendorf natural law and enlightenment classics An Introduction to the History of the Principal Kingdoms and States of Europe Samuel Pufendorf Translated by Jodocus Crull (1695) Edited and with an Introduction by Michael J. Seidler The Works of Samuel Pufendorf liberty fund Indianapolis This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest- known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 b.c. in the Sumerian city- state of Lagash. Introduction, annotations, charts, appendixes, bibliography, index © 2013 by Liberty Fund, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Frontispiece: The portrait of Samuel Pufendorf is to be found at the Law Faculty of the University of Lund, Sweden, and is based on a photoreproduction by Leopoldo Iorizzo. Reprinted by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Pufendorf, Samuel, Freiherr von, 1632–1694 [Einleitung zu der Historie der vornehmsten Reiche und Staaten so itziger Zeit in Europa sich befi nden. English] An introduction to the history of the principal kingdoms and states of Europe Samuel Pufendorf; translated by Jodocus Crull (1695); edited and with an introduction by Michael J. -

O John Adams in the Netherlands G

L ESSON ONE Y John Adams in the NetherlandsZ 1781–1783 Sources: Adams Family Correspondence. Volume 5. Edited by Richard Alan Ryerson, et al. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1993. Adams, John. “Correspondence of the Late President Adams.” Boston Patriot 20 April 1811: 1. Adams, John. “Correspondence of the Late President Adams.” Boston Patriot 24 April 1811: 1. Adams, John. “Letterbook, 28 April 1782–12 December 1785.” Microfilm Reel 106, Adams Family Papers. Massachusetts Historical Society. Papers of John Adams. Volume 11. Edited by Gregg L. Lint, Richard Alan Ryerson, et al. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003. Papers of John Adams. Volume 12. Edited by Gregg L. Lint, Richard Alan Ryerson, et al. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004. Papers of John Adams. Volume 13. Edited by Gregg L. Lint, C. James Taylor, et al. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006. Papers of John Adams. Volume 14. Edited by Gregg L. Lint, C. James Taylor, et al. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, publication forthcoming. 2 Y The Dutch TreatyZ After serving in the Continental Congress from 1774–1777, John Adams was elected by his fellow Patriots to serve his country in a new capacity. He was named a joint commissioner, and sailed for France accompanied by his son, John Quincy. Adams returned to Boston in 1779, and served in the Massachusetts Convention, single- handedly drafting the Commonwealth’s constitution of 1780. This constitution is the world’s oldest written constitution still in effect. -

Aus Den Akten Der Prozesse Gegen Die Erzberger-Mörder

Dokumentation AUS DEN AKTEN DER PROZESSE GEGEN DIE ERZBERGER-MÖRDER Vorbemerkung In den Sommern 1921 und 1922 schuf eine Kette politischer Morde und Mord versuche an republikanischen Politikern eine höchst gespannte, bürgerkriegsähnliche Situation in Deutschland. Am 9. Juni 1921 war der Führer der Münchener USPD, Gareis, Mördern zum Opfer gefallen; wenig später erlag Matthias Erzberger den Pistolenschüssen nationalistischer Fanatiker. Anfang Juni 1922 verübte man - aller dings erfolglos - ein Attentat auf Philipp Scheidemann, und am 24. Juni 1922 wurde Walther Rathenau auf der Fahrt ins Auswärtige Amt ermordet. Während die Urheber des Gareis-Mordes bis heute unbekannt geblieben sind, gelang es der badischen Polizei recht bald, Heinrich Tillessen und Heinrich Schulz als Erzberger- Mörder zu identifizieren. Es handelte sich bei ihnen um ehemalige Freikorpskämp fer und Angehörige der Marine-Brigade Ehrhardt, der inzwischen aufgelösten Truppe, die den Kapp-Putsch getragen hatte. Ihrer Verhaftung entzogen sie sich damals durch Flucht ins Ausland. Erst nach 1945 faßte man sie und machte ihnen den Prozeß. Im Zuge der Fahndung nach den Rathenau-Mördern fielen 1922 auch die beiden Scheidemann-Attentäter Hustert und Oehlschläger der Polizei in die Hände. Auch sie hatten früher der Marine-Brigade Ehrhardt angehört. Der beiden Mör der Rathenaus konnte die Polizei nur tot habhaft werden. Auch sie kamen aus der Brigade Ehrhardt, was ebenfalls von zahlreichen Helfern und Mitwissern galt, unter denen sich bezeichnenderweise ein Bruder des Erzberger-Mörders Heinrich Tillessen befand. Von Anfang an war in der Öffentlichkeit, besonders auf der Linken, der Ver dacht geäußert worden, hier sei eine weitverzweigte rechtsradikale „Mörder-Organi sation" am Werke, die mit ihren Aktionen das Signal zur reaktionären Gegenrevo lution geben wolle. -

GENTLEMAN Diversity

GENTLEMAN Diversity Gentleman : Liens www.gentleman-music.com www.myspace.com/gentleman SORTIE LE 12 AVRIL 2010 REGGAE / DANCEHALL A 35 ans à peine, Gentleman s’est imposé comme un TRACKLISTING infatigable ambassadeur du reggae. Fort d’albums magistraux 1. The Reason tels que “Journey To Jah“ et “Confidence”, il a en effet donné à 2. Ina Time Like Now ce genre un nouveau profil caractéristique et une pertinence 3. Lonely Days que le reggae avait perdu depuis l’époque de Bob Marley. 4. Regardless Parallèlement, Gentleman s’est depuis longtemps forgé une 5. It No Pretty réputation internationale et est considéré comme 6. I Got To Go incontournable dans plusieurs pays européens ainsi qu’en 7. The Finish Line Amérique du Sud, en Afrique et même aux Etats-Unis. 8. Changes 9. To The Top Feat. Christopher Gentleman envisage son cinquième album studio, intitulé Martin “Diversity“, comme un défi musical pour lui-même, mais aussi 10. No Time To Play 11. Fast Forward pour ses fans et les attentes qu’ils peuvent avoir. Rares en effet 12. Hold On Strong sont les musiciens allemands aussi imprégnés de roots reggae, 13. Moment of Truth pour autant Gentleman peut parfaitement faire un 14. Tempolution feat. Red Roze tabac du jour au lendemain sur un riddim dancehall et n’hésite 15. Another Melody feat. Tanya d’ailleurs pas dans cet album à aborder une grande variété de Stephens styles et de textures et à se lancer dans des collaborations. 16. Help feat. Million Stylez 17. Along The Way feat. Patrice L’entourage de Gentleman a un peu changé : son nouveau 18.