Key River Walleye Spawning Bed Rehabilitation Summary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C94) and Lower Moon River Conservation Reserve (C90

Moon River Conservation Reserve (C94) and Lower Moon River Conservation Reserve (C90) Statement of Conservation Interest March 2005 Moon River Conservation Reserve (C94) and Lower Moon River Conservation Reserve (C90) Statement of Conservation Interest Ministry of Natural Resources Parry Sound District Prepared with the assistance of: Meteek & Company Huntsville, Ontario March 2005 i Approval Statement We are pleased to approve this Statement of Conservation Interest for Moon River Conservation Reserve (C94) and Lower Moon River Conservation Reserve (C90). Together these two conservation reserves provide protection for approximately 15 kilometres of diverse habitats along the Moon River, from just west of Highway 400 (formerly Highway 69) to Arnolds Bay and The Massasauga Provincial Park on the Georgian Bay shoreline. Moon River Conservation Reserve (C94) is the upstream component of these two protected areas. It consists of 457 hectares of Crown land, located in southern Freeman Ward in the Area Municipality of Georgian Bay, in the District of Muskoka. The site is approximately seven kilometres southwest of the hamlet of Mactier. At its closest point on the east it is about ½ kilometre west of Highway 400, and it abuts Lower Moon River Conservation Reserve at its west boundary. This conservation reserve, located in Hills’ ecological Site District 5E-7, includes steep rocky slopes and low cliffs on the Moon River. The surrounding uplands support representative sugar maple and old hemlock forests growing on gently sloping hills with shallow sandy soils or bare bedrock. It provides habitat for the nationally threatened eastern Massasauga rattlesnake and the threatened eastern hog- nosed snake. Lower Moon River Conservation Reserve (C90) is a 2723 hectare area of Crown land, located about 10 kilometres due west of the hamlet of Mactier. -

Club Activities

Volume 41, Number 3 March – April 2007 Club Activities Indoor: Meetings begin at 7:30 pm on the second Tuesday of the month, October to June at St. Andrew’s United Church, 89 Mountainview Road South (at Sinclair) in Georgetown unless stated otherwise. Feb. 13: Central and South America, and the Bruce Peninsula. Bev Whatmough will be giving a presentation on some of the flora and fauna, and a look at the new Bruce Peninsula Park and Fathom Five Park interpretive centre. Mar. 13: Re-introduction of Elk into Ontario. Meagan Hazell will speak about her research on the release of large ruminants into Ontario Apr. 10: Halton Natural Areas Inventory. Andrea Dunn, Conservation Halton, will be talking on the results of the Sixteen Mile Creek Monitoring Study. Andrea was the coordinator of the project. Outdoor: Trips begin at the Niagara Escarpment Commission (NEC) parking lot at Guelph and Mountainview Road, Georgetown, unless stated otherwise. If you would like to meet the group at the trip site, please speak to the trip leader for the location and directions to the starting point. Jan. 21: Burlington Waterfowl. Meet 8:00 am. In case of inclement weather, check ahead with the trip leaders, Kelly Bowen and Andrew Kellman (905) 873-7338 Feb.18: Butterfly Conservatory, Niagara Falls, Ontario. Meet at the NEC parking lot at 8:00 am, or at the conservatory at about 9:30 am. Admission is $11 for adults. This should be a great opportunity to photograph butterflies and get a winter taste of the tropics! Depending on the weather and the group’s interests we may do some birding along the Niagara River or Lake Ontario in the afternoon. -

STATUS of WALLEYE in the GREAT LAKES: CASE STUDIES PREPARED for the 1989 WORKSHOP Edited by Peter J

STATUS OF WALLEYE IN THE GREAT LAKES: CASE STUDIES PREPARED FOR THE 1989 WORKSHOP edited by Peter J. Colby Ministry of Natural Resources Fisheries Research Section, Walleye Unit 435 S. James Street P.O. Pox 5000 Thunder Day, Ontario, Canada P7C 5G6 Cheryl A. Lewis Ministry of Natural Resources Glenora Fisheries Station R. R. #4 Picton, Ontario, Canada KOK 2T0 Randy L. Eshenroder Great Lakes Fishery Commission 1451 Green Road Ann Arbor, MI 48105-2898 Citation (general): Colby, P. J., C. A. Lewis, and R. L. Eshenroder, [ED.]. 1991. Status of walleye in the Great Lakes: case studies prepared for the 1989 workshop. Great Lakes Fish. Comm. Spec. Pub. 91-l. 222 p. Citation (example for individual paper): Schram, S. T., J. R. Atkinson, and D. L. Pereira. 1991. Lake Superior walleye stocks : status and management, p. l-22. In P. J. Colby, C. A. Lewis, and R. L. Eshenroder [ed.]. Status of walleye in the Great Lakes: case studies prepared for the 1989 workshop. Great Lakes Fish. Comm. Spec. Pub. 91-l. Special Publication No. 91-1 GREAT LAKES FISHERY COMMISSION 1451 Green Road Ann Arbor, MI 48105 January 1991 The case studies in this publication were produced as preparatory material for the Walleye Rehabilitation Workshop held June 5-9, 1990 at the Franz-Theodore Stone Laboratory at Put-in-Ray, Ohio. This workshop was sponsored by the Great Lakes Fishery Commission's Board of Technical Experts. For a number of years, Henry H. Regier had urged the Board to initiate such a study to document recent changes in walleye populations that were particularly evident inwestern Lake Erie. -

Henvey Inlet Wind Appendix

Henvey Inlet Wind LP Henvey Inlet Wind Transmission Line Appendix B9. Route A Cultural Heritage Assessment Report Henvey Inlet Wind LP Henvey Inlet Wind Cultural Heritage Assessment Report Transmission Line – Route A Unorganized Townships of Mowat, and Blair, District of Parry Sound, Ontario Prepared by: AECOM 410 – 250 York Street, Citi Plaza 519 673 0510 tel London, ON, Canada N6A 6K2 519 673 5975 fax www.aecom.com Project Number: 60341251 Date: August 2015 Henvey Inlet Wind LP Henvey Inlet Wind Cultural Heritage Assessment Report Transmission Line – Route A Statement of Qualifications and Limitations The attached Report (the “Report”) has been prepared by AECOM Canada Ltd. (“Consultant”) for the benefit of the client (“Client”) in accordance with the agreement between Consultant and Client, including the scope of work detailed therein (the “Agreement”). The information, data, recommendations and conclusions contained in the Report (collectively, the “Information”): is subject to the scope, schedule, and other constraints and limitations in the Agreement and the qualifications contained in the Report (the “Limitations”); represents Consultant’s professional judgement in light of the Limitations and industry standards for the preparation of similar reports; may be based on information provided to Consultant which has not been independently verified; has not been updated since the date of issuance of the Report and its accuracy is limited to the time period and circumstances in which it was collected, processed, made or issued; must be read as a whole and sections thereof should not be read out of such context; was prepared for the specific purposes described in the Report and the Agreement; and in the case of subsurface, environmental or geotechnical conditions, may be based on limited testing and on the assumption that such conditions are uniform and not variable either geographically or over time. -

2019 Lake Huron Lake Sturgeon Working Group Report

This document is intended to provide an update regarding lake sturgeon activities within the Lake Huron basin. Please contact the agency leads listed for more information about a specific project. 2019 Lake Huron Sturgeon Working Group Report Prepared by members: Justin Chiotti (Chair) U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Alpena FWCO Dave Borgeson Michigan Department of Natural Resources Lori Criger U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Marquette Biological Station Chris Davis Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Paul Ripple Bay Mills Indian Community Jason Smith Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians Brad Silet Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians J. Barry Weldon Little River Band of Ottawa Indians Erik Olsen Grand Traverse Bay Band of Chippewa Indians And non‐members: Russell Aikens Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians Ed Baker Michigan Department of Natural Resources Andrew Briggs Michigan Department of Natural Resources Stephen Chong Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Kris Dey Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians Rich Drouin Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Dave Fielder Michigan Department of Natural Resources Christopher Holbrook U.S. Geological Survey – Great Lakes Science Center Darryl Hondorp U.S. Geological Survey – Great Lakes Science Center Kevin Kapuscinski Lake Superior State University Jeffrey Jolley Michigan Department of Natural Resources Amber Johnston Michigan State University Doug Larson Department of Fisheries and Wildlife – Michigan State University Thomas P. Loch Michigan State University Lisa O’Connor Fisheries and Oceans Canada Ed Roseman U.S. Geological Survey – Great Lakes Science Center Kim Scribner Department of Fisheries and Wildlife – Michigan State University Esteban Soto University of California‐Davis Jeff Speers Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Lexi Sumner Anishinabek/Ontario Fisheries Resource Center Frank Zomer Bay Mills Indian Community Location: Southern Lake Huron and Upper St. -

Regulation Plan Map of Fisheries Management Zone 14

Statutory Order and Regulation / Decrets, Ministry of LEGEND NOTES: ordonnances et reglements statutaires No. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Natural 1. Map projection, grid, and coordinates are in UTM NAD 83 Zone 17, unless SCHEDULE No. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Wetland Area, Permanent Ontario Resources Digital Mapping Transportation FMZ Boundary otherwise noted. 2. Survey instructions from the Surveyor General must be obtained prior to Geographic Provincial Park & Crown establishing any of the boundaries on the ground. CERTIFICATE OF SURVEYOR GENERAL DATE COMPLETED _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Waterways Townships Game Preserve 3. "C/L OF ROAD" means the centreline of the pavement/gravel or the SHEET 1 OF 17 I HEREBY CERTIFY THAT THIS PLAN HAS BEEN FILED centreline of the median where the highway is divided. Railway Lakes 4. "C/L OF RAILWAY" denotes the centreline of all tracks where tracks exist or WITH THE OFFICE OF THE SURVEYOR GENERAL OF the centreline of bed where no tracks exist. 0 1020304050 Regulation Plan of Fisheries ONTARIO IN THE MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES This plan was compiled from data sets supplied by the Land 5. Where necessary all limits are extended unless otherwise noted. ON THE DAY OF Information Ontario (LIO) Warehouse, Ontario Roads Network and 6. Where a Fisheries Management Zone limit crosses a body of water along a road FMZ other information of record in the Ministry of Natural Resources. -

Lodge & Activity Overview

www.diamondkeylodge.com Lodge & Activity Overview Ver.01242011 Contents 1. Welcome 2. Recent Improvements at Diamond Key Lodge 3. Diamond Key: The Main Lodge 3. Diamond Key: The Cabins 3. Diamond Key: Food Options 4. Diamond Key: Frequently Asked Questions www.diamondkeylodge.com 4. Contact Information 4. Location & Maps 4. Our Rates & Packages 5. Location & Maps 5. Arrival and Departure Times 6. Fishing Schedules & Lures 7. Fishing Schedules & Lures Continued 8. Fish Master & Best Photo Contest 9. Kayak Adventures 9. Families & Fun 10.Other Activities 10.Pets 11.What to Bring 11.Boats and Safety 11.Bringing your own boat or rent one? 12.Emergencies Welcome My name is Peter Turkstra. I grew up fishing here in the North Shore Islands area and fell in love with the scenery and fishing. My wife Karen and I hope you will as well. The quality of the fishing is reknowned. Most people target golden walleye (pickerel), trophy Northern Pike, Muskie and small and large mouth bass. In many ways, you will find a feeling of remoteness that is normally only enjoyed at fly-in camps. We hope that you love the area as much as we do! Location www.diamondkeylodge.com Diamond Key Lodge is located at the mouth of the Key River in the Georgian Bay. We launch at the Key River at Hwy #69 and arrive at the Lodge by boat access – it is a beautiful ride out. The North East Corner of Georgian Bay and the North Shore Delta of Pickerel and French Rivers are a treasure. They are now protected by the Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve http://www.gbbr.ca as well as the French River Provincial Park system. -

Natural Heritage Assessment: Records Review Report

Henvey Inlet Wind LP Henvey Inlet Wind Henvey Inlet Wind Energy Centre Natural Heritage Assessment: Records Review Report Final Henvey Inlet Wind LP Henvey Inlet Wind Henvey Inlet Wind Energy Centre – Natural Heritage Assessment: Records Review Report – Final Prepared by: AECOM 105 Commerce Valley Drive West, Floor 7 905 886 7022 tel Markham, ON, Canada L3T 7W3 905 886 9494 fax www.aecom.com Project Number: 60341251 Date: January, 2016 Henvey Inlet Wind LP Henvey Inlet Wind Henvey Inlet Wind Energy Centre – Natural Heritage Assessment: Records Review Report – Final Statement of Qualifications and Limitations The attached Report (the “Report”) has been prepared by AECOM Canada Ltd. (“Consultant”) for the benefit of the client (“Client”) in accordance with the agreement between Consultant and Client, including the scope of work detailed therein (the “Agreement”). The information, data, recommendations and conclusions contained in the Report (collectively, the “Information”): is subject to the scope, schedule, and other constraints and limitations in the Agreement and the qualifications contained in the Report (the “Limitations”); represents Consultant’s professional judgement in light of the Limitations and industry standards for the preparation of similar reports; may be based on information provided to Consultant which has not been independently verified; has not been updated since the date of issuance of the Report and its accuracy is limited to the time period and circumstances in which it was collected, processed, made or issued; must be read as a whole and sections thereof should not be read out of such context; was prepared for the specific purposes described in the Report and the Agreement; and in the case of subsurface, environmental or geotechnical conditions, may be based on limited testing and on the assumption that such conditions are uniform and not variable either geographically or over time. -

Key River Fish Habitat Assessment

Key River Fish Habitat Assessment Executive Summary The Eastern Georgian Bay Stewardship Council (EGBSC) received funding from Environment and Climate Change Canada to carry out a 32-month project to assess spawning, nursery, rearing, and foraging habitat in eight tributaries to eastern Georgian Bay, which included the Key River. Fish habitat assessments were focused on Walleye, Lake Sturgeon, and Sucker species, between the river mouths and the first major spawning area or barrier to fish passage. Spawning bed enhancement work was completed at Ludgate and Portage Lake Outlet in fall 2015. Follow-up monitoring was completed in 2016 and a more detailed habitat assessment was carried out in 2017. During the 2017 spawning season, EGBSC visited Ludgate and Portage Lake Outlet seventeen (17) times between April 18 and June 20. Basic water chemistry measurements (water temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, conductivity) were recorded on all site visits and were generally within the expected range for Canadian Shield waters. Three stations were set up at Ludgate and four at Portage Lake Outlet to measure water velocity and water level fluctuations. All but one of the velocity measurements was under 2.0 m/s, and would likely not limit Walleye, Sucker, or Lake Sturgeon movement. Fish should be able to easily move throughout and past Ludgate, up to Portage Lake Outlet. It is unknown whether the rapids at Portage Lake Outlet serve as a barrier to fish passage further upstream. Water levels at both sites fluctuated throughout the spawning and egg incubation periods. Despite this, the newly created habitat at both sites was observed to be functioning as intended with sufficient water depth over the habitat. -

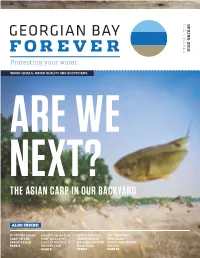

Protecting Your Water

VOL 7, ISSUEVOL 7, 2 SPRING 2016 Protecting your water. WATER LEVELS, WATER QUALITY AND ECOSYSTEMS ARE WE NEXT? THE ASIAN CARP IN OUR BACKYARD ALSO INSIDE: STOPPING ASIAN UPDATE ON NATIVE DONOR PROFILE: GBF USES DNA CARP IN THE FISH: WALLEYE, GEORGIAN BAY — PROFILING — GREAT LAKES LAKE STURGEON, & MAKING LASTING WHO’S WHO IN THE PAGE 4 SUCKER FISH MEMORIES WATER? PAGE 8 PAGE 9 PAGE 10 WAUKESHA, WISCONSIN'S Georgian Bay Forever is a community response to WATER DIVERSION APPLICATION the growing need for major research and education to sustain the Georgian Bay aquatic ecosystem and the quality of life its communities and visitors enjoy. We help monitor the Bay’s well being, throughout the seasons, year after year. We fund the research needed to protect the environmental health of Georgian Bay and the surrounding bodies of wa- ter. Using our research findings, we inform and educate the general public and governments about threats to environmental health and propose possible solutions. Lake Michigan Through workshops and seminars we Waukesha are educating the Georgian Bay community. By teaming up with reputable institutions, we enhance the credibility of our research and we strengthen our ability to protect what’s at stake. Georgian Bay Forever, formerly the GBA Foundation, is a registered Canadian charity (#89531 1066 RR0001). We work with the Great Lakes Basin Conservancy in ow do you balance people's expand- encouraging local communities to request the United States, as well as other stakeholder groups ing needs for safe drinking water water from the Great Lakes, instead of caring all around the Great Lakes. -

French River Provincial Park: a Historic Waterway Through Canadian Shield Gneiss; Geotours Northern Ontario Series

French River Provincial Park A Historic Waterway Through Canadian Shield Gneiss Between Parry Sound and the city of Greater Sudbury, Highway 69 crosses a rocky Canadian Shield landscape characterized by forested bedrock knolls, hills, wetlands and many small lakes. Ninety kilometres north of Parry Sound, Highway 69 passes through French River Provincial Park. The French River, connecting Lake Nipissing with Georgian Bay, has been an important waterway for First Nations. It was also a vital link in the canoe route for French explorers, fur traders and voyageurs between Montreal, the upper Great Lakes and the far West. The French River has been designated a Canadian Heritage River and remains a very popular recreational canoe route. French River Provincial Park protects this historic waterway. The park has an excellent visitor centre, with easy access, that highlights the history, geology and ecology of this famous waterway. Trails and a suspension bridge provide striking views of the river’s rock-walled gorge. French River Provincial Park protects the historic canoe A typical Canadian Shield landscape at Key River along Highway 69, south of French route from Georgian Bay to Lake Nipissing River Provincial Park. French River Provincial Park How to get there Canadian Shield and Gneiss French River Provincial Park Visitor Centre is 60 km south of French River Provincial Park sits near the southern limits of the Canadian Shield, a vast Greater Sudbury along Highway 69. (Note that when the and largely unsettled region of Canada known for its rocky landscapes, thin soils and four-laning of Highway 69 is completed, the highway will be abundant lakes and wetlands. -

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide Ontario Highway #69 "Trans Canada Highway,The Georgian Bay Route

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide Ontario Highway #69 "Trans Canada Highway,The Georgian Bay Route. Sudbury to Parry Sound and Highway #400" Kms ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Junction of Highway #17 ( North to City of Sudbury, Ontario. West to City of Sault Ste Marie, The Trans Canada Highway Ontario. South to City of Barrie, Ontario, City of Toronto, Ontario. ) & Highway #69 (The This route has access to Provincial Parks, Killarney, Grundy Trans Canada Highway) Lake,Sturgeon Bay, Killbear, Oastler Lake, 0.1 Photo - View from highway Driving south on the Trans Canada Highway. 0.4 Ontario Provincial Police At highway Station 3.0 Ontario Information Centre West side of highway 3.3 Carol's Campground, East side of highway. The RV, campground is located on the banks of Ontario Richard Lake, Ontario. 145 Sites, with electric hookups. 4.9 Roadside Highway Turnout West side of highway 6.5 Pine Grove Golf Club, West side of highway. Pine Grove Golf Club 18 hole Golf Course. Ontario 14.3 Junction of Highway #537 North to Community of Wanup, Ontario. North access to Wahnapitae, Ontario. 14.6 Point of Interest Crossing The Wahnapitae River, Ontario. The river is approximately 120 km in length, flowing into Georgian Bay, Ontario. 15.2 Roadside Highway East and West side of highway Turnouts 20.0 Community of Estaire, Access from highway Ontario 26.0 Roadside Highway East and west side of highway Turnouts 29.4 Roadside Highway East and west side of highway Turnouts 32.4 Junction of Highway #637 Access to Killarney Ontario, Provincial Park 58 km's west, 120 campsites, flush toilets, showers.