Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load for Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Sediment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

Summary of Lease Applications 9-23-20.Xlsx

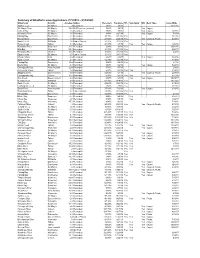

Summary of Shellfish Lease Applications (1/1/2015 - 9/23/2020) Waterbody County AcreageStatus Received CompleteTFL Sanctuary WC Gear Type IssuedDate Smith Creek St. Mary's 3 Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 11/21/16 St. Marys River St. Mary's 16.2 GISRescreen (revised) 1/6/15 1/6/15 Yes Cages Calvert Bay St. Mary's 2.5Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 YesCages 2/28/17 Wicomico River St. Mary's 4.5Recorded 1/8/15 1/27/15 YesCages 5/8/19 Fishing Bay Dorchester 6.1 Recorded 1/12/15 1/12/15 Yes 11/2/15 Honga River Dorchester 14Recorded 2/10/15 2/26/15Yes YesCages & Floats 6/27/18 Smith Creek St Mary's 2.6 Under Protest 2/12/15 2/12/15 Yes Harris Creek Talbot 4.1Recorded 2/19/15 4/7/15 Yes YesCages 4/28/16 Wicomico River Somerset 26.7Recorded 3/3/15 3/3/15Yes 10/20/16 Ellis Bay Wicomico 69.9Recorded 3/19/15 3/19/15Yes 9/20/17 Wicomico River Charles 13.8Recorded 3/30/15 3/30/15Yes 2/4/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 1.7 Under Protest 3/31/15 3/31/15 Yes Chester River Kent 4.9Recorded 4/6/15 4/9/15 YesCages 8/23/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 2.1 Recorded 4/23/15 4/23/15 Yes 9/19/16 Fishing Bay Dorchester 12.4Recorded 5/4/15 6/4/15Yes 6/1/16 Breton Bay St. -

Choptank Tributary Summary: a Summary of Trends in Tidal Water Quality and Associated Factors, 1985-2018

Choptank Tributary Summary: A summary of trends in tidal water quality and associated factors, 1985-2018. June 7, 2021 Prepared for the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) Partnership by the CBP Integrated Trends Analysis Team (ITAT) This tributary summary is a living document in draft form and has not gone through a formal peer review process. We are grateful for contributions to the development of these materials from the following individuals: Jeni Keisman, Rebecca Murphy, Olivia Devereux, Jimmy Webber, Qian Zhang, Meghan Petenbrink, Tom Butler, Zhaoying Wei, Jon Harcum, Renee Karrh, Mike Lane, and Elgin Perry. 1 Contents 1. Purpose and Scope .................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Location ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Watershed Physiography .................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Land Use .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Land Use ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 Tidal Waters and Stations ................................................................................................................... 8 3. Tidal -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Summary of Decisions Regarding Nutrient and Sediment Load Allocations and New Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Restoration Goals

To: Principal Staff Committee Members and Representatives of Chesapeake Bay “Headwater” States From: W. Tayloe Murphy, Jr., Chair Chesapeake Bay Program Principals’ Staff Committee Subject: Summary of Decisions Regarding Nutrient and Sediment Load Allocations and New Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Restoration Goals For the past twenty years, the Chesapeake Bay partners have been committed to achieving and maintaining water quality conditions necessary to support living resources throughout the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. In the past month, Chesapeake Bay Program partners (Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Chesapeake Bay Commission) have expanded our efforts by working with the headwater states of Delaware, West Virginia and New York to adopt new cap load allocations for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment. Using the best scientific information available, Bay Program partners have agreed to allocations that are intended to meet the needs of the plants and animals that call the Chesapeake home. The allocations will serve as a basis for each state’s tributary strategies that, when completed by April 2004, will describe local implementation actions necessary to meet the Chesapeake 2000 nutrient and sediment loading goals by 2010. This memorandum summarizes the important, comprehensive agreements made by Bay watershed partners with regard to cap load allocations for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediments, as well as new baywide and local SAV restoration goals. Nutrient Allocations Excessive nutrients in the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries promote undesirable algal growth, and thereby, prohibit light from reaching underwater bay grasses (submerged aquatic vegetation or SAV) and depress the dissolved oxygen levels of the deeper waters of the Bay. -

War of 1812 Travel Map & Guide

S u sq u eh a n n a 1 Westminster R 40 r e iv v e i r 272 R 15 anal & Delaware C 70 ke Chesapea cy a Northeast River c o Elk River n 140 Havre de Chesapeake o 97 Grace City 49 M 26 40 Susquehanna 213 32 Flats 301 13 795 95 1 r e Liberty Reservoir v i R Frederick h 26 s 9 u B 695 Elk River G 70 u 340 n Sa p ssaf 695 rass 83 o Riv w er r e d 40 e v i r R R Baltimore i 13 95 v e r y M c i 213 a dd c le o B R n 70 ac iv o k e R r M 270 iv e 301 r P o to m ac 15 ster Che River 95 P 32 a R t i v a 9 e r p Chestertown 695 s 13 co R 20 1 i 213 300 1 ve r 100 97 Rock Hall 8 Leesburg 97 177 213 Dover 2 301 r ive r R e 32 iv M R 7 a r k got n hy te Ri s a v t 95 er e 295 h r p 189 S e o e C v 313 h ve i r C n R R e iv o er h 13 ka 267 495 uc 113 T Whitehall Bay Bay Bridge 50 495 Greensboro 193 495 Queen Milford Anne 7 14 50 Selby 404 Harrington Bay 1 14 Denton 66 4 113 y P 258 a a B t u rn 404 x te 66 Washington D.C. -

Manokin River Watershed Characterization

Manokin River Watershed Characterization May 2001 In support of Somerset County’s Watershed Restoration Action Strategy for the Manokin River Watershed Product of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources In partnership with Somerset County Parris N. Glendening, Governor Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Lt. Governor Sarah J. Taylor-Rogers, Secretary Stanley K. Arthur, Deputy Secretary David Burke, Director, Chesapeake and Coastal Watershed Service (CCWS) Maryland Department of Natural Resources Tawes State Office Building 580 Taylor Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Telephone for CCWS 410-260-8739 Call toll free: 1-877-620-8DNR TTY for the Deaf: 1-410-974-3683 www.dnr.state.md.us The Mission of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources To inspire people to enjoy and live in harmony with their environment, and to protect what makes Maryland unique – our treasured Chesapeake Bay, our diverse landscapes, and our living and natural resources. The facilities and services of the Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, age, national origin, physical or mental disability. Important Contributors to the Manokin River Watershed Characterization Robin Bunting Somerset County Director of Recreation and Parks Max Chambers Flomax Marine Nursery Larry Fykes, Manager, Somerset Soil Conservation District Roman Jesien University of Maryland Eastern Shore Joan Kean Dept. of Technical and Community Services Tom Lawton Dept. of Technical and Community Services Somerset County Alphabetical Order Earl -

Defining the Nanticoke Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Indigenous Cultural Landscapes Study for the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail: Nanticoke River Watershed December 2013 Kristin M. Sullivan, M.A.A. - Co-Principal Investigator Erve Chambers, Ph.D. - Principal Investigator Ennis Barbery, M.A.A. - Research Assistant Prepared under cooperative agreement with The University of Maryland College Park, MD and The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, MD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Nanticoke River watershed indigenous cultural landscape study area is home to well over 100 sites, landscapes, and waterways meaningful to the history and present-day lives of the Nanticoke people. This report provides background and evidence for the inclusion of many of these locations within a high-probability indigenous cultural landscape boundary—a focus area provided to the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay and the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Advisory Council for the purposes of future conservation and interpretation as an indigenous cultural landscape, and to satisfy the Identification and Mapping portion of the Chesapeake Watershed Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Cooperative Agreement between the National Park Service and the University of Maryland, College Park. Herein we define indigenous cultural landscapes as areas that reflect “the contexts of the American Indian peoples in the Nanticoke River area and their interaction with the landscape.” The identification of indigenous cultural landscapes “ includes both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife therein associated with historic lifestyle and settlement patterns and exhibiting the cultural or esthetic values of American Indian peoples,” which fall under the purview of the National Park Service and its partner organizations for the purposes of conservation and development of recreation and interpretation (National Park Service 2010:4.22). -

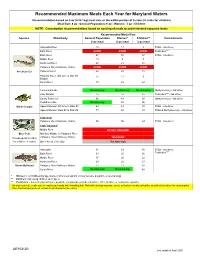

Recommended Maximum Fish Meals Each Year For

Recommended Maximum Meals Each Year for Maryland Waters Recommendation based on 8 oz (0.227 kg) meal size, or the edible portion of 9 crabs (4 crabs for children) Meal Size: 8 oz - General Population; 6 oz - Women; 3 oz - Children NOTE: Consumption recommendations based on spacing of meals to avoid elevated exposure levels Recommended Meals/Year Species Waterbody General PopulationWomen* Children** Contaminants 8 oz meal 6 oz meal 3 oz meal Anacostia River 15 11 8 PCBs - risk driver Back River AVOID AVOID AVOID Pesticides*** Bush River 47 35 27 PCBs - risk driver Middle River 13 9 7 Northeast River 27 21 16 Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor AVOID AVOID AVOID American Eel Patuxent River 26 20 15 Potomac River (DC Line to MD 301 1511 9 Bridge) South River 37 28 22 Centennial Lake No Advisory No Advisory No Advisory Methylmercury - risk driver Lake Roland 12 12 12 Pesticides*** - risk driver Liberty Reservoir 96 48 48 Methylmercury - risk driver Tuckahoe Lake No Advisory 93 56 Black Crappie Upper Potomac: DC Line to Dam #3 64 49 38 PCBs - risk driver Upper Potomac: Dam #4 to Dam #5 77 58 45 PCBs & Methylmercury - risk driver Crab meat Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 96 96 24 PCBs - risk driver Crab "mustard" Middle River DO NOT CONSUME Blue Crab Mid Bay: Middle to Patapsco River (1 meal equals 9 crabs) Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor "MUSTARD" (for children: 4 crabs ) Other Areas of the Bay Eat Sparingly Anacostia 51 39 30 PCBs - risk driver Back River 33 25 20 Pesticides*** Middle River 37 28 22 Northeast River 29 22 17 Brown Bullhead Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 17 13 10 South River No Advisory No Advisory 88 * Women = of childbearing age (women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, or are nursing) ** Children = all young children up to age 6 *** Pesticides = banned organochlorine pesticide compounds (include chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, or heptachlor epoxide) As a general rule, make sure to wash your hands after handling fish. -

Watersheds.Pdf

Watershed Code Watershed Name 02130705 Aberdeen Proving Ground 02140205 Anacostia River 02140502 Antietam Creek 02130102 Assawoman Bay 02130703 Atkisson Reservoir 02130101 Atlantic Ocean 02130604 Back Creek 02130901 Back River 02130903 Baltimore Harbor 02130207 Big Annemessex River 02130606 Big Elk Creek 02130803 Bird River 02130902 Bodkin Creek 02130602 Bohemia River 02140104 Breton Bay 02131108 Brighton Dam 02120205 Broad Creek 02130701 Bush River 02130704 Bynum Run 02140207 Cabin John Creek 05020204 Casselman River 02140305 Catoctin Creek 02130106 Chincoteague Bay 02130607 Christina River 02050301 Conewago Creek 02140504 Conococheague Creek 02120204 Conowingo Dam Susq R 02130507 Corsica River 05020203 Deep Creek Lake 02120202 Deer Creek 02130204 Dividing Creek 02140304 Double Pipe Creek 02130501 Eastern Bay 02141002 Evitts Creek 02140511 Fifteen Mile Creek 02130307 Fishing Bay 02130609 Furnace Bay 02141004 Georges Creek 02140107 Gilbert Swamp 02130801 Gunpowder River 02130905 Gwynns Falls 02130401 Honga River 02130103 Isle of Wight Bay 02130904 Jones Falls 02130511 Kent Island Bay 02130504 Kent Narrows 02120201 L Susquehanna River 02130506 Langford Creek 02130907 Liberty Reservoir 02140506 Licking Creek 02130402 Little Choptank 02140505 Little Conococheague 02130605 Little Elk Creek 02130804 Little Gunpowder Falls 02131105 Little Patuxent River 02140509 Little Tonoloway Creek 05020202 Little Youghiogheny R 02130805 Loch Raven Reservoir 02139998 Lower Chesapeake Bay 02130505 Lower Chester River 02130403 Lower Choptank 02130601 Lower -

Somerset County, Maryland

- H L 350 350 S S t t e e o o s s m r m r e e SSoommeerrsseett 350350 H L - Annemessex River landscape, Aerial photograph by Joey Gardner, 2016 Native Americans, Explorers and Settlement of Somerset n August 22, 1666, Cecil Calvert, Lord proprietor of the province of Maryland, authorized legislation creating OSomerset County, and 350 years later in this anniversary year, we look back as well as forward in celebration to honor and cherish our past as we continue to live here in the present and future. Somerset’s first inhabitants, however, were the native tribes of the lower Eastern Shore. Native American occupation of the region dates back thousands of years; its earliest inhabitants occupied a landscape far different than today with much lower sea levels. Spanning over fifteen to twenty thousand years, native American habitation matured from hunter-gathers to settled communities of tribes who resided along the region’s A characteristic Paleo-Indian fluted numerous waterways, many of which still carry their names. The Pocomoke, Manokin, projectile point from Maryland’s Eastern Annemessex, Monie and Wicomico waterways are named for these native tribes. Shore, Nancy Kurtz. Native American occupation is also represented by the thousands of artifacts that turn up in the soil, or through the written historical record as Anglo-American explorers, traders and ultimately settlers interacted with them across the peninsula. One of the earliest explorers to leave a written record of his visit, describing the local inhabitants as well as their activities was Giovanni da Verrazano, who, during the 1520s, traveled along what later became Somerset County. -

Annual Report the Brock Environmental Center

Moving Forward 2016 ANNUAL REPORT THE BROCK ENVIRONMENTAL CENTER Leading the Way It has been a heady year for the Brock Environmental Center (pictured right). Located in Virginia Beach, Virginia, the facility welcomed tens of thousands of visitors, including Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe—who experienced one of the center’s most unique features when he sampled a glass of Brock’s treated rainwater (Brock is the first commercial building in the U.S. permitted to treat rainwater for drinking). The center has received 20 awards, including the 2015 Engineering News-Record’s “Best Green Project.” In May, Brock achieved a designation that was more than a year in the making: International Living Future Institute’s Living Building Certification. Brock is only the tenth building in the world to achieve the organization’s “full petal” certification, which requires a building to produce more energy than it uses over the course of a year, in addition to other strict criteria. Through the Brock Center, CBF is inspiring visitors and demonstrating how each of us can reduce our footprint and actually give back to the environment. contents To schedule a tour of the Brock educate ................................................................................... 2 Environmental Center, please advocate ................................................................................. 4 call 757/622-1964 x3312 or email [email protected]. litigate ..................................................................................... 6 restore ...................................................................................