Tango As Exoticist Other in Hollywood Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARIS VISION 2018 5 6 Sur Lascèneinternationale

Paris vision Commerces Gotan Eterno 2018 4 ÉDITO Chers amis, net regain d’optimisme des ménages, du retour des touristes et de l’arrivée en J’ai le plaisir de vous présenter France de nouvelles enseignes étrangères. Paris Vision 2018. Five Guys est l’un de ces acteurs, dans C’est une édition toute particulière car un secteur très en vogue, celui de la nous fêtons le dixième anniversaire de restauration. Philippe Cebral, son Directeur cette publication, qui avait vu le jour la du Développement, détaille dans ces première fois en 2008 dans un tout autre pages la stratégie immobilière du nouveau environnement de marché, j’allais dire à roi des burgers et ses ambitions pour les une autre époque. années à venir. Le projet d’origine était simple : produire Le marché locatif des bureaux en Île- une étude différente, vivante, fidèle à la de-France est au diapason, avec un réalité du terrain vécue par les équipes de volume placé au plus haut depuis 2007 Knight Frank, mais aussi par nos clients, et une activité particulièrement intense qui ont bien voulu chaque année nous sur le créneau des grandes transactions. PHILIPPE PERELLO livrer leur vision et nous en dire plus sur L’accélération de l’activité économique Associé Gérant leur stratégie. Qu’ils en soient tous ici a sans aucun doute joué son rôle. La Knight Frank France chaleureusement remerciés. croissance française est désormais en ligne avec la moyenne européenne, le monde Le deuxième objectif de Paris Vision des affaires a retrouvé la confiance, et Paris était de livrer une analyse prospective s’est vu attribuer l’organisation des Jeux s'inscrivant dans un temps long. -

DVIDA American Smooth Silver Syllabus Figures

Invigilation Guidance/ DVIDA/SYLLABUS/ Current'as'of'October'15,'2015' Extracted'from: Dance$Vision$International$Dancers$Association, Syllabus$Step$List$ Revised/May/2014 Invigilation Guidance/ AMERICAN)SMOOTH) / DVIDA American Smooth Bronze Syllabus Figures *Indicates figure is not allowable in NDCA Competitions. Revised January 2014. View current NDCA List Waltz Foxtrot Tango V. Waltz Bronze I 1A. Box Step 1. Basic 1A. Straight Basic 1. Balance Steps 1B. Box with Underarm Turn 2. Promenade 1B. Curving Basic 2A. Fifth Position Breaks 2. Progressive 3A. Rock Turn to Left 2A. Promenade Turning Left 2B. Fifth Position Breaks 3A. Left Turning Box 3B. Rock Turn to Right 2B. Promenade Turning Right with Underarm Turn 3B. Right Turning Box 3. Single Corté 4. Progressive Rocks Bronze II 4A. Balance Steps 4. Sway Step 5A. Open Fan 3. Reverse Turn 4B. Balance and Box 5A. Sway Underarm Turn 5B. Open Fan with 4. Closed Twinkle 5. Simple Twinkle 5B. Promenade Underarm Turn Underarm Turn 6. Two Way Underarm Turn 6A. Zig Zag in Line 6. Running Steps 7. Face to Face – Back to Back 6B. Zig Zag Outside Partner 7. Double Corté 7. Box Step 8A. Reverse Turn Bronze III 8A. Reverse Turn 8. Twinkle 8B. Reverse Turn with 5A. Crossbody Lead 8B. Reverse Turn with 9. Promenade Twinkles Outside Swivel 5B. Crossbody Lead with Underarm Turn 10A. Turning Twinkles to 9. Right Side Fans Underarm Turn 9A. Natural Turn Outside Partner 10. Contra Rocks 6. Hand to Hand 9B. Natural Turn with 10B. Turning Twinkles to Outside 11A. Change of Places 7A. Forward Progressive Underarm Turn Partner with Underarm Turn 11B. -

Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective Alejandro Marcelo Drago University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Drago, Alejandro Marcelo, "Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective" (2008). Dissertations. 1107. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY ALEJANDRO MARCELO DRAGO 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 ABSTRACT INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. -

Social Tango

Social Tango Richard Powers Argentine tango has been popular around the world for over a century. Therefore it has evolved into several different forms. This doc describes social tango, sometimes called American tango. The world first saw tango when Argentine dancers brought it to Paris around 1910. It quickly became the biggest news in Paris—the 1912 Tangomania. Dancers around the world fell in love with tango and added it to their growing repertoire of social dances. When we compare 1912 European and North American tango descriptions to Argentine tango manuals from the same time, we see that the northern hemisphere dancers mostly got it right, dancing the same steps in the same style as the Argentines. Then as time went on, social dancers had no reason to change it. It wasn't broken, so why fix it? Today's social tango is essentially the continuation of the original 1912 Argentine tango. There have been a few evolutionary changes over time, like which foot to start on, but they're relatively minor compared to the greater changes that have been made to the other two forms of tango. Ironically, some people call this American Style tango. This is to differentiate it from International Style (British) tango, but it's nevertheless odd to call the nearly-unchanged original Argentine tango "American," unless one means South American. Many dancers in the world know social tango so this is worth learning. That doesn't mean it's "better" than the other forms of tango—that depends on one's personal preference. But social tango is a very useful kind of tango for dancing with friends at parties, weddings and ocean cruises. -

3671 Argentine Tango (Gold Dance Test)

3671 ARGENTINE TANGO (GOLD DANCE TEST) Music - Tango 4/4 Tempo - 24 measures of 4 beats per minute - 96 beats per minute Pattern - Set Duration - The time required to skate 2 sequences is 1:10 min. The Argentine Tango should be skated with strong edges and considerable “élan”. Good flow and fast travel over the ice are essential and must be achieved without obvious effort or pushing. The dance begins with partners in open hold for steps 1 to 10. The initial progressive, chassé and progressive sequences of steps 1 to 6 bring the partners on step 7 to a bold LFO edge facing down the ice surface. On step 8 both partners skate a right forward outside cross in front on count 1 held for one beat. On step 9, the couple crosses behind on count 2, with a change of edge on count 3 as their free legs are drawn past the skating legs and held for count 4 to be in position to start the next step, crossed behind for count 1. On step 10 the man turns a counter while the woman executes another cross behind then change of edge. This results in the partners being in closed hold as the woman directs her edge behind the man as he turns his counter. Step 11 is strongly curved towards the side of the ice surface. At the end of this step the woman momentarily steps onto the RFI on the “and” between counts 4 and 1 before skating step 12 that is first directed toward the side barrier. -

Samba, Rumba, Cha-Cha, Salsa, Merengue, Cumbia, Flamenco, Tango, Bolero

SAMBA, RUMBA, CHA-CHA, SALSA, MERENGUE, CUMBIA, FLAMENCO, TANGO, BOLERO PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL DAVID GIARDINA Guitarist / Manager 860.568.1172 [email protected] www.gozaband.com ABOUT GOZA We are pleased to present to you GOZA - an engaging Latin/Latin Jazz musical ensemble comprised of Connecticut’s most seasoned and versatile musicians. GOZA (Spanish for Joy) performs exciting music and dance rhythms from Latin America, Brazil and Spain with guitar, violin, horns, Latin percussion and beautiful, romantic vocals. Goza rhythms include: samba, rumba cha-cha, salsa, cumbia, flamenco, tango, and bolero and num- bers by Jobim, Tito Puente, Gipsy Kings, Buena Vista, Rollins and Dizzy. We also have many originals and arrangements of Beatles, Santana, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison, Guns & Roses and Rodrigo y Gabriela. Click here for repertoire. Goza has performed multiple times at the Mohegan Sun Wolfden, Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, River Camelot Cruises, festivals, colleges, libraries and clubs throughout New England. They are listed with many top agencies including James Daniels, Soloman, East West, Landerman, Pyramid, Cutting Edge and have played hundreds of weddings and similar functions. Regular performances in the Hartford area include venues such as: Casona, Chango Rosa, La Tavola Ristorante, Arthur Murray Dance Studio and Elizabeth Park. For more information about GOZA and for our performance schedule, please visit our website at www.gozaband.com or call David Giardina at 860.568-1172. We look forward -

KT 20-9-2017 .Qxp Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2017 THULHIJJA 29, 1438 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Man arrested Hamza Bin Bahrain accused Lions overpower for growing Laden: Heir of stoking Giants; Stafford marijuana3 to Qaeda?6 tension11 throws16 for 2 TDs Trump warns Iran and Min 26º Max 47º High Tide N Korea’s ‘rocket man’ 10:53 Low Tide ‘America First’ president addresses United Nations 05:03 & 17:59 32 PAGES NO: 17335 150 FILS UNITED NATIONS: US President Donald Trump said yes- terday that the United States will be forced to “totally Hijri holiday destroy” North Korea unless Pyongyang backs down from its nuclear challenge, mocking North Korean leader Kim Jong Un as a “rocket man” on a suicide mis- on Thursday sion. Loud murmurs filled the green-marbled UN General Assembly hall when Trump issued his sternest Safeguarding Husseiniyas warning yet to North Korea, whose ballistic missile launches and nuclear tests have rattled the globe. KUWAIT: Ministries and all government institutions Unless North Korea backs down, he said, “We will nationwide will be closed tomorrow to mark the Hijri have no choice but to totally destroy North Korea.” New Year’s holiday, Kuwait’s Civil Service Commission “Rocket man is on a suicide mission for himself and his (CSC) announced yesterday. Meanwhile, workplaces regime,” he said. North Korea’s mission to the United of unconventional and special nature will determine Nations did not immediately respond to a request for their holidays as they see fit, a statement issued by comment on Trump’s remarks. A junior North Korean the CSC noted. -

Moses in Switzerland | Norient.Com 25 Sep 2021 03:01:16 Moses in Switzerland PODCAST by Moses Iten

Moses in Switzerland | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 03:01:16 Moses in Switzerland PODCAST by Moses Iten In the philosophical DJ-Set «The B Side of Switzerland» and the radio Podcast «Stranger than caribbean music: My swiss roots» the swiss-australian artist Moses Iten travelles through Switzerland and back to his own swiss past. Based in Melbourne he is gaining an international reputation as a DJ and producer with the Cumbia Cosmonauts – a fresh outlook to search for remains and revivals of «real» Swiss folk music. The B Side of Switzerland Swiss-Australian artist Moses Iten recently travelled around the tiny nation of Switzerland by bus, train, plane and steamship, along the way digging in record stores for forgotten classics, cult jewels, experimental gems, and interviewing some of the artists behind music Made in Switzerland. Moses introduces us to the likes of a man who spent ten years recording the sounds of steamboats; a spaghetti western soundtrack composer; a son of yodellers who is a well-known dancehall producer; and a duo of like-minded sonic explorers sharing some of their insights. This road trip through the sonic landscape of Switzerland is the B-Side to a documentary Moses produced for Into The Music, which explored his quest as a musician of how to best produce contemporary music that is https://norient.com/podcasts/moses-in-switzerland Page 1 of 7 Moses in Switzerland | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 03:01:16 representative of his birth country. In this B-Side version, Switzerland and its music is ripped apart and put together again without paying much attention to tradition or history, but sense of place remains all-important in this philosophical DJ set. -

Le Cas Paris-Buenos Aires Charlotte Renaudat Ravel

Villes Capitales et dialogues interculturels : dispositifs, lieux et médiations thématiques : le cas Paris-Buenos Aires Charlotte Renaudat Ravel To cite this version: Charlotte Renaudat Ravel. Villes Capitales et dialogues interculturels : dispositifs, lieux et médiations thématiques : le cas Paris-Buenos Aires. Sciences de l’information et de la communication. 2019. dumas-02530212 HAL Id: dumas-02530212 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02530212 Submitted on 2 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Master professionnel Mention : Information et communication Spécialité : Communication Entreprises et institutions Option : Entreprises, institutions, culture et tourisme Villes Capitales et dialogues interculturels : dispositifs, lieux et médiations thématiques Le cas Paris - Buenos Aires Responsable de la mention information et communication Professeure Karine Berthelot-Guiet Tuteur universitaire : Dominique Pagès Nom, prénom : RENAUDAT RAVEL Charlotte Promotion : 2018 Soutenu le : 18/06/2019 Mention du mémoire : Très bien École des hautes études en sciences de l'information et de la communication – Sorbonne Université 77, rue de Villiers 92200 Neuilly-sur-Seine I tél. : +33 (0)1 46 43 76 10 I fax : +33 (0)1 47 45 66 04 I celsa.fr TABLE DES MATIÈRES REMERCIEMENTS 2 DOMAINES D’INVESTIGATION ET MOTS CLÉS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 Dispositifs de médiation interculturelle entre les villes-mondes : la construction d’un regard sur l’autre dans le paysage urbain 13 A. -

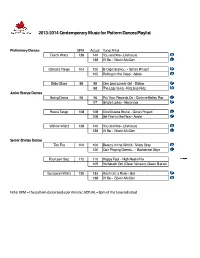

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist Preliminary Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Dut ch Walt z 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Can ast a Tan go 104 100 El Capitalismo... - Gotan Project 105 Rolling in the Deep - Adele Baby Bl ues 88 88 One Less Lonely Girl - Bieber 88 The Lazy Song - Kidz bop Kidz Ju n i o r Br o n z e D a n ce s Sw i n g Da n c e 96 96 Put Your Records On - Corinne Bailey Rae 97 Single Ladies - Beyoncee Fi est a Tango 108 108 Una Musica Brutal - Gotan Project 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele Willow Waltz 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Se ni or Br onze Da nce s Ten Fox 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Fo ur t een St ep 112 110 Happy Feet - High Heels Mix 109 Hollaback Girl (Clean Version)-Gwen Stefani Eu r o p ean Wal t z 135 133 Kiss from a Rose - Seal 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Note: BPM = the pattern dance beats per minute; ACTUAL = bpm of the tune indicated _____________________________________________________________________________________ 2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist pg2 Junior Silver Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Keat s Foxt r ot 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Ro ck er Fo xt r o t 104 104 Black Horse & the Cherry Tree - KT Tunstall 104 Never See Your Face Again- Maroon 5 Harris Tango 108 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele 111 Gotan Project - Queremos Paz American Walt z 198 193 Fal l i n - Al i ci a Keys -

Amateur Mul Dance & Scholarship Entry Form

Form Leader: Age: DOB: mm/dd/yy: NDCA#: Studio: F Follower: Age: Teacher: Amateur Mul� Dance & Scholarship Entry Form DOB: mm/dd/yy: NDCA#: Phone: Adult contact name: Email: Amateur Rhythm Amateur Int'l Ballroom $ Per Category Dances Couple Category Dances $ Per Couple Sun Day - Session 10 Sun Day - Session 10 40 Amateur Under 21 - American Rhythm Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero Amateur Under 21 - Int'l Ballroom Waltz, Tango, V. Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep 40 Wed Eve - Session 3 Fri Day - Session 6 Pre-Novice - American Rhythm Cha Cha, Rumba 40 Pre-Novice - Int'l Ballroom Waltz, Tango 40 Novice - American Rhythm Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing 40 Pre-Novice - Int'l Ballroom Foxtrot, Quickstep 40 Pre-Championship - American Rhythm Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero 50 Novice - Int'l Ballroom Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep 40 Senior Open - American Rhythm (35+) Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero 50 Pre-Championship - Int'l Ballroom Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot, Quickstep 40 Open Am - Am Rhythm Scholarship Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero, Mambo 55 Senior Open - Int'l Ballroom (35+) Waltz, Tango, V. Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep 50 $ Total Amateur Rhythm Dance Entries: Masters Open - Int'l Ballroom (51+) Waltz, Tango, V. Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep 50 Fri Eve - Session 7 55 Open Am - Int'l Ballroom Scholarship Waltz, Tango, V. Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep Amateur Smooth $ $ Per Total Amateur Int'l Ballroom Dance Entries: Category Dances Couple Sun Day - Session 10 Amateur Under 21 - American Smooth Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot, V. Waltz 40 Amateur Int'l La�n Thu Eve - Session 5 Category Dances $ Per Pre-Novice - American Smooth Waltz, Tango 40 Couple Sun Day - Session 10 Novice - American Smooth Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot 40 Amateur Under 21 - Int'l La�n Cha Cha, Samba, Rumba, Paso Doble, Jive 40 Pre-Championship - American Smooth Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot, V. -

Danc-Dance (Danc) 1

DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 DANC 1131. Introduction to Ballroom Dance DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 Credit (1) Introduction to ballroom dance for non dance majors. Students will learn DANC 1110G. Dance Appreciation basic ballroom technique and partnering work. May be repeated up to 2 3 Credits (3) credits. Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. This course introduces the student to the diverse elements that make up Learning Outcomes the world of dance, including a broad historic overview,roles of the dancer, 1. learn to dance Figures 1-7 in 3 American Style Ballroom dances choreographer and audience, and the evolution of the major genres. 2. develop rhythmic accuracy in movement Students will learn the fundamentals of dance technique, dance history, 3. develop the skills to adapt to a variety of dance partners and a variety of dance aesthetics. Restricted to: Main campus only. Learning Outcomes 4. develop adequate social and recreational dance skills 1. Explain a range of ideas about the place of dance in our society. 5. develop proper carriage, poise, and grace that pertain to Ballroom 2. Identify and apply critical analysis while looking at significant dance dance works in a range of styles. 6. learn to recognize Ballroom music and its application for the 3. Identify dance as an aesthetic and social practice and compare/ appropriate dances contrast dances across a range of historical periods and locations. 7. understand different possibilities for dance variations and their 4. Recognize dance as an embodied historical and cultural artifact, as applications to a variety of Ballroom dances well as a mode of nonverbal expression, within the human experience 8.