July-Sept 2015 Pdf.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Foxpro

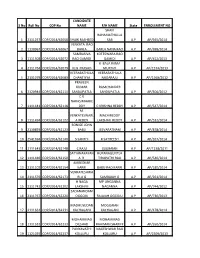

RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT BHINDER IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/2/2003 33835 Sh.Bhagwati Lal Choubisa N.A.* 2 R/223/2007 47749 Sh.Laxman Giri Goswami L.T.M. 3 R/393/2018 82462 Sh.Manoj Kumar Regar N.A.* 4 R/3668/2018 85737 Kum.Kalavati Choubisa N.A.* 5 R/2130/2020 93493 Sh.Lokesh Kumar Regar N.A.* 6 R/59/2021 94456 Sh.Kailash Chandra Khariwal L.T.M. 7 R/3723/2021 98120 Sh.Devi Singh Charan N.A.* Total RAWF Members = 2 Total Terminated = 0 Total Defaulter = 0 N.A.* => Not Applied for Membership, L.T.M. => Life Time Member, Termi => Terminated Member RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT GOGUNDA IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/460/1975 6161 Sh.Purushottam Puri NIL + 1250 = 1250 1250 16250 2 R/337/1983 11657 Sh.Kanhiya Lal Soni 6250+2530+1250=10030 10125 25125 3 R/125/1994 18008 Sh.Yuvaraj Singh L.T.M. -

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

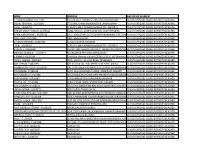

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

Name Address Nature of Payment P

NAME ADDRESS NATURE OF PAYMENT P. NAVEENKUMAR -91774443 NO 139 KALATHUMEDU STREETMELMANAVOOR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED VISHAL TEKRIWAL -31262196 27,GOPAL CHANDRAMUKHERJEE LANEHOWRAH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED BHIKAM SINGH THAKUR -21445522 JABALPURS/O UDADET SINGHVILL MODH PIPARIYA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ATINAINARLINGAM S -91828130 NO 2 HINDUSTAN LIVER COLONYTHAGARAJAN STREET PAMMAL0CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED USHA DEVI -27227284 VPO - SILOKHARA00 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUSHMA BHENGRA -19404716 A-3/221,SECTOR-23ROHINI CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAKESH V -91920908 NO 304 2ND FLOOR,THIRUMALA HOMES 3RD CROSS NGRLAYOUT,CLAIMS CHEQUES ROOPENA ISSUED AGRAHARA, BUT NOT ENCASHED KRISHAN AGARWAL -21454923 R/O RAJAPUR TEH MAUCHITRAKOOT0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED K KUMAR -91623280 2 nd floor.olympic colonyPLOT NO.10,FLAT NO.28annanagarCLAIMS west, CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MOHD. ARMAN -19381845 1571, GALI NO.-39,JOOR BAGH,TRI NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ANIL VERMA -21442459 S/O MUNNA LAL JIVILL&POST-KOTHRITEH-ASHTA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAMBHAVAN YADAV -21458700 S/O SURAJ DEEN YADAVR/O VILG GANDHI GANJKARUI CHITRAKOOTCLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD SHADAB -27188338 H.NO-10/242 DAKSHIN PURIDR. AMBEDKAR NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD FAROOQUE -31277841 3/H/20 RAJA DINENDRA STREETWARD NO-28,K.M.CNARKELDANGACLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAJIV KUMAR -13595687 CONSUMER APPEALCONSUMERCONSUMER CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MUNNA LAL -27161686 H NO 524036 YARDS, SECTOR 3BALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUNIL KUMAR -27220272 S/o GIRRAJ SINGHH.NO-881, RAJIV COLONYBALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED DIKSHA ARORA -19260773 605CELLENO TOWERDLF IV CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED R. -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H. -

Eit^ Stpfhr

OnlySAeDeugrted 4 D€»€hpeJhy-^ eit^ sTPfhr 2204/03/2021/WT 20 ^5^, 2021 WTPT - M%r?TT arf^ra^ R^lim 01/2021 ftHI<t> 08.02.2021 'dNf^d 3TTjT^f2ff ^ 31-|5b^l"tt> STTffR 'TFT f^'o X / (^\\^ - lOO) 1 3001 JITENDRA KUMAR PATEL M OBC 72.00 2 3002 VIJENDRA SINGH THAKUR M EWS 70.00 3 3003 INDU RATHOR F OBC 75.00 4 3004 BHAVISHYA RATHORE M OBC 52.00 5 3005 SWALI VERMA F OBC 75.00 6 3008 AJAY SINGH CHOUHAN M OBC 72.00 7 3009 VARSHA JADHAV F ST 45.00 8 3010 SANDEEP KUMAR M OBC 48.00 9 3011 CELINA ROOPAM PARGI F ST 74.00 10 3012 HEMENDRA MUCHHALA M OBC 53.00 11 3013 RINKOO NARGAWE F ST 42.00 12 3014 SUMIT KUMAR KUSHWAHA M OBC . 72.00 Page 1 'TFT _ 100) 13 3015 ANOOP SINGH YADAV M OBC 83,00 14 3016 ADITI AWASTHI F EWS 78.00 15 3017 MOHAMMED LUKMAN KHAN M OBC 50.00 16 3018 PREETI UIKEY F ST 80.00 17 3019 ARUN KUSHWAH M OBC 85.00 18 3020 PREETI LAKRA F ST 55.00 19 3021 DIWAKAR RAO KADAM M EWS 48.00 20. 3022 SHARDA DAWAR F ST 72.00 21 3023 RITESH JAVARIYA M OBC 48.00 22 3025 SAGAR BHASKER M ST 54.00 23 3028 TARUN GOYAL M ST 62.00 24 3030 ADITYA SINGH CHAUHAN M OBC 84.00 25 3031 VIKRAM KUMAR M OBC 60.00 26 3032 RAM SINGH EEKWALE M ST 43.00 27 3033 SOURABH BAGHEL M ST 75.00 28 3034 KRISHNAPAL SINGH SASTIYA M ST 72.00 29 3035 SHIVANGI CHOUDHARY F OBC 48.00 30 3036 MONICA YADAV F OBC 70.00 31 3037 VIDESH KUMAR SHARMA M EWS 75.00 32 3039 SHAFFALI NAGAR F OBC 85.00 33 3041 RAHUL HAMAD M OBC 57.00 V. -

Cultural Geography of the Jats of the Upper Doab, India. Anath Bandhu Mukerji Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1960 Cultural Geography of the Jats of the Upper Doab, India. Anath Bandhu Mukerji Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mukerji, Anath Bandhu, "Cultural Geography of the Jats of the Upper Doab, India." (1960). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 598. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE JATS OF THE UPPER DQAB, INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Anath Bandhu Muker ji B.A. Allahabad University, 1949 M.A. Allahabad University, 1951 June, I960 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Individual acknowledgement to many persons who have, di rectly or indirectly, helped the writer in India and in United States is not possible; although the writer sincerely desires to make it. The idea of a human geography of the Jats as proposed by the writer was strongly supported at the very beginning by Dr. G. R. Gayre, formerly Professor of Anthropo-Geography at the University of Saugor, M. P. , India. In the preparation of the preliminary syn opsis and initial thinking on the subject able guidance was constantly given by Dr. -

The Students Islamic Movement of India : the Story So Far Anshuman Behera

Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 Journal of Defence Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.idsa.in/journalofdefencestudies The Students Islamic Movement of India : The Story So Far Anshuman Behera To cite this article: Anshuman Behera (2013): The Students Islamic Movement of India: The Story So Far, Journal of Defence Studies, Vol-7, Issue-1.pp- 213-228 URL: http://www.idsa.in/jds/7_1_2013_The Students Islamic Movement of India_AnshumanBehera Please Scroll down for Article Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.idsa.in/termsofuse This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re- distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India. The Students Islamic Movement of India The Story So Far Anshuman Behera* The Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI) continues to pose serious threats to the national security of India. Despite having been banned for 12 years, SIMI, it has been alleged, works through radical outfits like the Popular Front of India (PFI) and its front organizations. It has also been charged with having links with terror outfits such as the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Harkat-ul-Jihad-al Islami Bangladesh (HuJI-B), and the Islami Chhatra Shibir (ICS) of Bangladesh. At the same time, the government’s decision to ban SIMI has been questioned by one section of its members. -

Madhya Pradesh Road Development Corporation Ltd. Details of All Participating Candidates for the Post of Manager (Tech.) Through GATE-2018

Madhya Pradesh Road Development Corporation Ltd. Details of all participating candidates for the post of Manager (Tech.) through GATE-2018 Common APPLICATION_NO FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME FATHERS_NAME DOB GEN CASTE DOMI HAND HOUSE STREET COLONY CITY STATE GSRegNo GS GSQMC GS GS Gate Rank DER CILE ITYPE Rank Total Obtain Score 1 MPRDCMT180668 ANKUR GUPTA UMA PATI GUPTA 1993-12-01 M अनारक्षित (UR) N N B1-58 PIPROLA KRIBHCO NAGAR SHAHJAHANPU UP CE18S75030100 13 26.9 100 86.67 947 00:00:00.000 R 2 MPRDCMT180160 ARJUN DANGE ANOOP KUMAR 1993-12-30 M अनारक्षित (UR) Y N HOUSE NO 1 ward no 7 , CHAKGHAT CHAKGHAT MP CE18S83006164 25 27 100 84.74 928 DANGE 00:00:00.000 maharan 3 MPRDCMT180472 NITIN GARG MUKESH GARG 1997-01-01 M अनारक्षित (UR) N N SHOP NO. 79-80 S.B. VIHAR SWEJ NEW SANGANER JAIPUR Rajasthan CE18S73041623 32 26.9 100 84.3 924 00:00:00.000 FARM ROAD 4 MPRDCMT180409 RAJESH KUMAR SURESH CHANDRA 1995-03-01 M अनारक्षित (UR) N N PLOT NO 51 VINAYAK VIHAR JHOTWARA JAIPUR Rajasthan CE18S83041766 51 26.9 100 82.77 909 00:00:00.000 NIWARU 5 MPRDCMT180467 VISHAL TYAGI KANTI KUMAR 1995-01-27 M अनारक्षित (UR) N N B-181 NTPC TOWNSHIP DADRI GHAZIABAD UP CE18S78013157 58 26.9 100 82.27 904 TYAGI 00:00:00.000 VIDYUT 6 MPRDCMT180300 YOGENDRA VYAS BALKRISHNA VYAS 1994-01-01 M अनारक्षित (UR) Y N 18 RAJASVA GRAM CHHATRIBAGH INDORE MP CE18S73039264 68 27 100 81.59 897 00:00:00.000 RAMDVAR 7 MPRDCMT180727 SHIVAM BHALLA SUSHIL BHALLA 1997-10-24 M अनारक्षित (UR) N N HOUSE NO 12 BARDAHIYA BAZAR NEAR BARDAHIYA KHALILABAD UP CE18S75015114 68 26.9 100 81.59 897 00:00:00.000 MASZID 8 MPRDCMT180319 AMARJEET KUMAR RAM KUMAR 1997-02-25 M अनारक्षित (UR) N N H NO. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Studies in Sindi society the anthropology of selected Sindi communities Siddiqi, A. H. A. How to cite: Siddiqi, A. H. A. (1968) Studies in Sindi society the anthropology of selected Sindi communities, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10150/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Studies in Sindi Society. The Anthropology of Selected Sindi Communities. Summary. The purpose of this thesis is to accept the fact that there is a territory called Sind which has possessed and still possesses a regional identity and then to exalniine the nature of society within it. The emphasis throughout is on social and cultural charac• teristics related as far as possible to the various forces affecting them and operating within them, a field of study lying between Social Geography eind Social Anthropology. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

India September 2010

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT INDIA 21 SEPTEMBER 2010 UK Border Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE INDIA 21 SEPTEMBER 2010 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN INDIA FROM 17 JULY – 16 SEPTEMBER 2010 REPORTS ON INDIA PUBLISHED OR FIRST ACCESSED SINCE 16 JULY 2010 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ......................................................................................... 1.01 Maps .............................................................................................. 1.11 2. ECONOMY ............................................................................................. 2.01 3. HISTORY ............................................................................................... 3.01 Mumbai terrorist attacks, November 2008 ................................. 3.03 General Election of April-May 2009 ............................................ 3.08 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ....................................................................... 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION ...................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM ................................................................................ 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 7.01 UN Conventions ........................................................................... 7.05 8. INTERNAL SECURITY SITUATION ............................................................. 8.01 Naxalite (Maoist) -

Institute Name India Rankings 2017 ID Discipline

Institute Name Nirma University India Rankings 2017 ID IR17-I-2-18406 Discipline Overall Parameter Enterpreneurship Name of the Graduating 3A.GPHE S.No. Student/Alumni/Faculty year(applicable for Name of the company incubated enterpreneur student/alumni) 1 Anisha Dinesh Gupta 2011 MR shah logistics 2 Ankur Maheshwari 2011 Locus Rags 3 Harsh B. Mehta 2011 Future automated solutions 4 Rohit Bhura 2011 Bhura Mining Company 5 Tanvi Dhamija 2011 Indiavaale 6 Prashant Shah 2011 Nisarg Soft Labs 7 Prashant Shah 2011 Digikonn Technology 8 Karishma Shah 2011 Ardorite Pvt. Ltd. 9 Parth Goyal 2011 Easy Vaccines Pvt. Ltd. 10 Nandish Pethani 2011 Nector Engineers Post Tensioning 11 Vishal Goti Vinubhai 2011 Deval Corporation 12 Sunny Marvania 2011 ORION Engineers Ltd. 13 Chaudhary Vijaykumar Motilal 2011 Business Consultant Pvt. Ltd. 14 Vatsal Shah 2011 Litmus Automation Pvt. Ltd. 15 Manil Patel 2011 Enertron Renewables Pvt. Ltd 16 Ronak Chiripal 2011 The Alchemists Ltd. 17 Kushal J Patel 2012 Daffodil Pharma & Posy Pharmachem 18 Anish Patel 2012 Aavya Developers 19 Hitesh Parghi 2012 Marutinandan Construction Palak Madhwani, Surbhi 20 2012 MagnADism Ltd. Saxena Ronak Koradiya, Sanket 21 2012 IConflux Technologies Pvt Ltd. Thakkar 22 Aakash Agrawal 2012 CTRL P HUB Ltd. 23 Faldu Siddarth C. 2012 Eracon Vitrified Pvt Ltd. 24 Sohil Patel 2012 Ciruitricks 25 Smit Ghelani 2012 Shree Bhavani Lodates 26 Parth Shah 2012 Helios Infra. Ltd. 27 Hemant Shah 2012 Banking Academy 28 Dipen Nawani 2012 Dipen Textiles 29 Sohil Patel 2012 Oizom Consultants 30 Tapas