Anticipating Flat Bush

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South & East Auckland

G A p R D D Paremoremo O N R Sunnynook Course EM Y P R 18 U ParemoremoA O H N R D E M Schnapper Rock W S Y W R D O L R SUNSET RD E R L ABERDEEN T I A Castor Bay H H TARGE SUNNYNOOK S Unsworth T T T S Forrest C Heights E O South & East Auckland R G Hill R L Totara Vale R D E A D R 1 R N AIRA O S Matapihi Point F W F U I T Motutapu E U R RD Stony Batter D L Milford Waitemata THE R B O D Island Thompsons Point Historic HI D EN AR KITCHENER RD Waihihi Harbour RE H Hakaimango Point Reserve G Greenhithe R R TRISTRAM Bayview D Kauri Point TAUHINU E Wairau P Korakorahi Point P DIANA DR Valley U IPATIKI CHIVALRY RD HILLSIDERD 1 A R CHARTWELL NZAF Herald K D Lake Takapuna SUNNYBRAE RD SHAKESPEARE RD ase RNZAF T Pupuke t Island 18 Glenfield AVE Takapuna A Auckland nle H Takapuna OCEAN VIEW RD kland a I Golf Course A hi R Beach Golf Course ro O ia PT T a E O Holiday Palm Beach L R HURSTMERE RD W IL D Park D V BEACH HAVEN RD NORTHCOTE R BAY RD R N Beach ARCHERS RD Rangitoto B S P I O B E K A S D A O D Island Haven I R R B R A I R K O L N U R CORONATION RD O E Blackpool H E Hillcrest R D A A K R T N Church Bay Y O B A SM K N D E N R S Birkdale I R G Surfdale MAN O’WA Hobsonville G A D R North Shore A D L K A D E Rangitawhiri Point D E Holiday Park LAK T R R N OCEANRALEIGH VIEW RD I R H E A R E PUPUKE Northcote Hauraki A 18 Y D EXMOUTH RD 2 E Scott Pt D RD L R JUTLAND RD E D A E ORAPIU RD RD S Birkenhead V I W K D E A Belmont W A R R K ONEWA L HaurakiMotorway . -

The Housing We'd Choose" Survey

The Housing We’d Choose A Study of Housing Preferences, Choices and Trade-Offs in Auckland Prepared for Auckland Council Date: May 2015 Status: Final Date: February 2015 The Housing We’d Choose A Study of Housing Preferences, Choices and Trade-Offs in Auckland A report prepared for the Research and Evaluation Unit (RIMU), Auckland Council Document reference: ACL055.014 Date of this version: May 2015 Report authors: Rodney Yeoman, Greg Akehurst Auckland Council Technical Report 2015/016 ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-0-908320-13-4 (Print) ISBN 978-0-908320-14-1 (PDF) Recommended citation Yeoman, R and Akehurst, G (2015). The housing we’d choose: a study of housing preferences, choices and trade- offs in Auckland. Auckland Council technical report, TR2015/016. Prepared by Market Economics Limited for Auckland Council. Auckland: Market Economics Limited Auckland Council Peer Review Panel This report has been peer reviewed by Auckland Council’s Peer Review Panel Approved for publication by: Regan Solomon, Manager, Research and Evaluation Unit Disclaimer Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this report, neither Market Economics Limited nor any of its employees shall be held liable for the information, opinions and forecasts expressed in this report. Market Economics Limited Level 5, 507 Lake Road PO Box 331 297, Takapuna www.me.co.nz Auckland 0740, NZ P 09 915 5510 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... -

Auckland Metro

5/08/2021 Change in Delivery Partner- Auckland Metro Dear Valued Customer Effective Monday 9th August Auckland Metro deliveries and pick ups will be completed by Mainfreight. Map and Suburb list below for confirmation of affected areas Auckland Metro Ellerslie, Greenlane, Middlemore, Mt Wellington, Mt Wellington, One Tree Hill, Onehunga, Otahuhu, Area 1 Panmure, Penrose, Remuera, Royal Oak, Southdown, Tamaki, Te Papapa. Airport Oaks, Auckland Airport, Balmoral, Blockhouse Bay, Botany Downs, Clover Park, Burswood, Dannemora, East Tamaki, Epsom, Farm Cove, Favona, Flat Bush, Glen Innes, Goodwood Heights, Greenmount, Highbrook, Highland Park, Hillsborough, Lynfield, Mangere, Mangere Bridge, Manukau, Area 2 Meadowbank, Morningside, Mt Albert, Mt Eden, Mt Roskill, Northpark, Otara, Pakuranga, Papatoetoe, Pt England, Remuera, Sandringham, St Johns, St Lukes, Stonefields, Sunnyhills, Three Kings, Totara Heights, Wiri Avondale, Birkenhead, Castor Bay, Chatswood, Clendon, Conifer Grove, Edmonton, Forrest Hill, Glen Eden, Glendene, Glendowie, Glenfield, Green Bay, Hauraki, Half Moon Bay, Highbury, Hillcrest, Howick, Kelston, Area 3 Kohimaramara, Manurewa, Milford, Mission Bay, New Lynn, Northcote, Northcote Point, Orakei, Pt Chevalier, St Heliers, Te Atatu Peninsula, Takanini, Takapuna, Totara Vale, Wairau Valley, Waterview, Wattle Downs, Western Springs, Westmere, Weymouth Albany, Alfriston, Arch Hill, Auckland Central, Bayswater, Bayview, Beach Haven, Belmont, Birkdale, Bucklands Beach, Campbells Bay, Cockle Bay, Eastern Beach, Eden Terrace, Fairview Heights, Freemans Bay, Grafton, Grey Lynn, Henderson, Henderson Valley, Herne Bay, Hobsonville, Kingsland, Mairangi Bay, Area 4 Massey, Murrays Bay, Newmarket, Newton, North Harbour, Papakura, Parnell, Ponsonby, Ranui, Rosedale, Rosehill, Rothesay Bay, Royal Heights, St Marys Bay, Sunnynook, Swanson, Titirangi, West Harbour, Westgate Westhaven Ardmore, Bombay, Browns Bay, Devonport, Drury, Greenhithe, Herald Island, Karaka, Kumeu, Pukekohe, Area 5 Ramarama, Redvale, Torbay . -

Part 3 New and Future Urban Expansion

PART 3 - CONTENTS PART 3 NEW AND FUTURE URBAN EXPANSION 3 .1 INTRODUCTION 3.1 .1 General 3.1 .2 Urban Development Strategy 3.1.3 New Urban Zoning 3. 1 .4 Future Development Zoning and Staging 3 . 1 . 5 Structure Plans 3.2 NEW DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVE AND POLICIES 3.3 CLENDON PARK 3.4 FLAT BUSH 3.5 BOTANY ROAD WEST 3 .6 HILL ROAD 3 .7 WOODSIDE HEIGHTS 3 .8 MANGEMANGEROA 3 .9 TE U KAIPO 3 .10 WESTNEY ROAD 3.11 MASSEY ROAD 3.12 ORUARANGI SOUTH CITY OF MANUKAU SECOND REVIEW PART 3 - NEW AND FUTURE URBAN EXPANSION 3.1 INTRODUCTION ( 3.1.1 General This part of the Scheme sets out the objectives and policies for the expansion of the City's urban area for the purpose of establishing the ultimate form of the City. An indication is given of the pattern and sequence in which development will occur and the means by which the releasing of land from rural to urban purposes will be implemented. Also included in this Part are structure plans for: Clendon Park Flat Bush Botany Road West Hill Road Woodside Heights Mangemangeroa Te U Kaipo Westney Road Massey Road Oruarangi South 3.1.2 Urban Development Strategy 3.1.2.1 Plan 3A gives an overview of Council's urban development strategy. The primary aim of the Council's future development policies is to achieve by way of controlled development the consolidation of the City in order to improve transport linkages and create a better relationship between home, work, shopping and recreational facilities. -

TR2015/016 the Housing We'd Choose. a Study of Housing

The Housing We’d Choose A Study of Housing Preferences, Choices and Trade-Offs in Auckland Prepared for Auckland Council Date: May 2015 Status: Final Date: February 2015 The Housing We’d Choose A Study of Housing Preferences, Choices and Trade-Offs in Auckland A report prepared for the Research and Evaluation Unit (RIMU), Auckland Council Document reference: ACL055.014 Date of this version: May 2015 Report authors: Rodney Yeoman, Greg Akehurst Auckland Council Technical Report 2015/016 ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-0-908320-13-4 (Print) ISBN 978-0-908320-14-1 (PDF) Recommended citation Yeoman, R and Akehurst, G (2015). The housing we’d choose: a study of housing preferences, choices and trade- offs in Auckland. Auckland Council technical report, TR2015/016. Prepared by Market Economics Limited for Auckland Council. Auckland: Market Economics Limited Auckland Council Peer Review Panel This report has been peer reviewed by Auckland Council’s Peer Review Panel Approved for publication by: Regan Solomon, Manager, Research and Evaluation Unit Disclaimer Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this report, neither Market Economics Limited nor any of its employees shall be held liable for the information, opinions and forecasts expressed in this report. Market Economics Limited Level 5, 507 Lake Road PO Box 331 297, Takapuna www.me.co.nz Auckland 0740, NZ P 09 915 5510 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... -

Social and Geographical Differences in Road Traffic Injury in the Auckland Region

Social and geographical differences in road traffic injury in the Auckland region Jamie Hosking, Shanthi Ameratunga, Daniel Exeter, Joanna Stewart Section of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Population Health, The University of Auckland Produced for Auckland Transport, 2013. ISBN: 978‐0‐473‐24259‐6 Acknowledgements This report was informed by a stakeholder reference group, the members of which are listed below. This report does not necessarily represent the views of the host organisations of reference group members. Laura Ager ACC Moses Alatini Safekids New Zealand Melanie Bartlett New Zealand Transport Agency Andrew Bell Auckland Transport Julie Chambers Auckland District Health Board Angie Cheong Auckland Transport Juanita deSenna Auckland Transport Greer Hawley Auckland Transport John Kelly New Zealand Police Peter Sandiford Waitemata District Health Board The assistance of the following people and organisations with this report was greatly appreciated: Bridget Kool, Carol Chelimo, Sandar Tin Tin and Alex Macmillan, University of Auckland, for advice on hospitalisation and mortality data and analysis, census data, and travel survey data David Drodskie, Auckland Transport, for providing CAS data Simon Gianotti, ACC, for advice on ACC road traffic injury data Joyce‐Anne Raihania, Injury Prevention Network of Aotearoa New Zealand (IPNANZ), for advice on road traffic injuries among Māori John Wallwork, New Zealand Transport Agency, for advice on use of Driver Licence Registry data Ministry of Transport, for provision of New Zealand Household Travel Survey data Koordinates.com and the Local Government Commission of the Department of Internal Affairs, for provision of data on Auckland local board areas This work includes Statistics New Zealand’s data which are licensed by Statistics New Zealand for re‐ use under the Creative Commons Attribution‐Noncommercial 3.0 New Zealand license. -

Commercial Member Directory

Commercial Member Directory Barfoot & Thompson Commercial 34 Shortland Street +64 9 3076300 [email protected] Auckland, 1140 www.barfoot.co.nz Title Name Email Phone # Commercial Referral Coordinator John Urlich [email protected] +64 21395396 Commercial Broker in Charge Peter Thompson [email protected] +64 9 3075523 Certifications Applies Service Tiers Applies ALC Commercial Division/Office BOMA Dedicated Commercial Agent(s) Build-to-suit Resi-Mercial Agent(s) CCIM CPM Lease negotiation SIOR Service Types Applies Network Affiliations Applies Hotel / Resort CBRE CORFAC Industrial CRESA Investment CW/DTZ Land / Agricultural JLL Knight Frank Landlord Rep NAI Leasing Newmark TCN Service Types Applies Logistics Medical Office Multi-Family Office Property Management Retail Tenant Rep City State / Province Country Ahuroa NZL Albany NZL Albany Heights NZL Alfriston NZL Algies Bay NZL Ararimu NZL Ardmore NZL Arkles Bay NZL Army Bay NZL Auckland NZL Avondale NZL Awhitu NZL Bay Of Islands NZL Bay View NZL Bay of Plenty NZL Bayswater NZL Bayview NZL Beach Haven NZL Beachlands NZL Belmont NZL Big Bay NZL Birkdale NZL Birkenhead NZL Birkenhead Point NZL Bland Bay NZL Blockhouse Bay NZL Bombay NZL Botany Downs NZL City State / Province Country Broadwood NZL Brookby NZL Browns Bay NZL Buckland NZL Bucklands Beach NZL Burswood NZL Cable Bay NZL Campbells Bay NZL Canterbury NZL Castor Bay NZL Central Otago NZL Chatswood NZL City Centre NZL Clarks Beach NZL Clendon Park NZL Clevedon NZL Clover Park NZL Coatesville NZL Cockle -

Local Board Information and Agreements Draft Long-Term Plan 2012-2022

DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS About this volume About this volume This is Volume Four of the four volumes that make up the draft LTP. It is set out in two parts, one which provides background on the role of local boards, their decision-making responsibilities and some general information about local board plans and physical boundaries. The second part contains the individual local board agreements for all 21 local boards, which contain detailed information about local activities, services, projects and programmes and the corresponding budgets for the period 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2013. Here we have also included additional information like ten-year budgets for each board and a capital projects list. What this volume covers: the status of draft local board agreements how to have your say during the public consultation period an overview of the local boards local board activities information on the development of local board plans and agreements local board financial information including a consolidated statement of expenditure on local activities about each local board, with an overview of the local board including their strategic priorities and a message from the chairperson draft local board agreements for each local board covering scope of activities levels of service and performance measures local activities including key initiatives and projects expenditure and funding notes to the local board agreements contact details, how to contact your local board, including individual contact details for each local board member an appendix to each Local Board information section which includes their expenditure statements and capital projects for the ten-year period 2012 to 2022. -

Manurewa Local Board

Proactive Release Submissions on the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy August 2019 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet has released the following submission received during its public consultation on the child and youth wellbeing strategy. Some of the information contained within this release is considered to not be appropriate to release and, if requested, would be withheld under the Official Information Act 1982 (the Act). Where this is the case, the information has been withheld, and the relevant section of the Act that would apply, has been identified. Where information has been withheld, no public interest has been identified that would outweigh the reasons for withholding it. Key to redaction codes and their reference to sections of the Act: 9(2)a – Section 9(2)(a): to protect the privacy of natural persons, including deceased people. An external party holds copyright on this material and therefore its re‐use cannot be licensed by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy – Submission Template This document is intended for individuals or groups who wish to make a formal submission on the child and youth wellbeing strategy. Please complete this template and email it to: [email protected] A guide to making a submission is available on the DPMC website https://dpmc.govt.nz/our- programmes/child-and-youth-wellbeing-strategy Submissions will close on Wednesday 5 December. Please provide details for a contact person in case we have some follow up questions. Contact Name: Sarah Colcord Email Address: [email protected] Phone Number: 09 262 5402 Organisation Name: Manurewa Local Board Organisation description: The Manurewa Local Board is the statutory body that represents (tell us about your organisation the communities of Manurewa, Wattle Downs, Weymouth, – i.e. -

Average Deprivation Scores for Census Area Units

Average Deprivation Scores for Census Area Units For administrative purposes, Statistics New Zealand The first table lists the CAUs, as well as the codes for divides the country into about 1900 Census Area Units the District Health Board (DHB) and Territorial Authority (CAUs) of unequal population size. Each is made up (TA) to which each belongs, and for each provides the of many meshblocks. At the time of the 2006 Census CAU deprivation decile and the population-weighted there were 1927 CAUs and 41,376 meshblocks. The average deprivation value. As with the NZDep2006 small NZDep2006 index of deprivation was created from area deciles, the value 1 indicates a CAU in the 10 per 23,786 NZDep2006 small areas that were, in general, cent least deprived CAUs in New Zealand, and the value either one meshblock, or two nearby meshblocks. 10 indicates that the CAU is in the 10 per cent most deprived CAUs. CAU averages and deciles are missing For many purposes it is useful to have an idea of the – indicated by a period – for CAUs where the usually deprivation characteristic of CAUs, which are often linked resident population was insufficient to calculate any to natural neighbourhoods, such as suburbs. Users component NZDep scores. should be aware though that there may be considerable variation in deprivation among the small areas that make An alphabetical index of the CAU names is provided after up the CAUs. This variation will be hidden when using an this table for cross-reference. average deprivation statistic for the CAU. Each CAU is part of one of the 21 DHBs. -

Activities and Services of Auckland Council Introduction

Part II: Activities and services Introduction PART II ACTIVITIES AND SERVICES OF AUCKLAND COUNCIL INTRODUCTION OVERVIEW Auckland Council provides a range of goods and services. These are detailed in the following sections where the activities undertaken by the council and its CCOs are described. Each section includes details of the expenditure, the projects and achievements together with the levels of service which were provided and details of the performance measures. The performance measures describe either what we set out to achieve or levels of customer satisfaction. Results show performance against the standard (target) we set ourselves. The sections provide information about: • the groups of activities undertaken by Auckland Council. Activities are grouped together because of their connectivity with each other • individual activities undertaken. Individual activities are goods and services delivered to the community – for example, the provision of facilities, providing grants and the performance of regulatory and other functions. Note that some activities are provided by the CCOs. While each set of performance measures, results and commentaries cover the full activity provided by the council and Group, only the portions funded directly by the council are covered in the financial statements. A summary of the total expenditure of the CCOs is covered in the CCO section. Following the sections about the council’s activities, there is coverage of the activities of the 21 local boards, and this is followed by the CCO section. The council has 11 groups of activities: • Community • Lifestyle and Culture • Economic Development • Planning and Regulation • Environmental Management • Solid Waste • Water Supply and Wastewater • Stormwater • Transport • Commercial and Investment • Governance Auckland Council Report 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012 52 Part II: Activities and services Introduction EXPLAINING OUR GROUP ACTIVITY STATEMENTS Each group activity statement is broken down into the following headings: OVERVIEW Why the council is involved. -

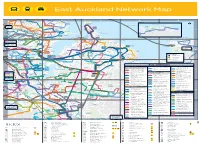

East Auckland Network Map

J002915_East Auckland Public Transport Guide.indd 4-5 East Auckland Network Map d Gl R ov er R d i Kohimarama Cl Karaka Musick Pt Beach Bay Reserve R Vale R u d r Ri k amaki D T A ut d Ronaki R Mission u Churchill Park r d t Poly d a C go ihill ve c nR R Bay de i k d N Ave School R S S A p d l ei l n l l ght a V l t St n Bay a S n atatu t ne S T o R M ri t a e d h A e l B C D E T d a M nd e St Heliers el R S n wy a e v ne C t k l d e e s a d t e t P v A S i ea e ia h t S v Howick t R a t H R l P r e a a l A im a a R S d o o R A e v a d l r Y e e l a n Golf Club A e k i C h A d e u n s a m D t dar v e S Kohimarama g i a n St n o i il m a n u te a r e M K Churchill Park i s d Maraetai o School g ns B Kohimarama r Paun e S s a l D t S e R a C K t e Rd t m d t Sy h e t S n u Madills R lo C es h d t d l t P d v d hi t A r e L i a l Farm Res a e e Rd e k a n r r l c o o fi R y e e v i P t Bucklands u R el o w s y ng d Orakei R K a S d A b d H m P A le u C A To ai St y K a v le o w e v r C View Bay M Beach u F a Omana Beach Ed D Dingle a um k d e l r te pe l s d B Cr Go R r e i Pohutukawa s d t Dell d h n de t A r A c u e n Cr o n v S d r e St Riddell R St nRd d o t t e d p gh g le c Bay Shelly o S Saye R d G k P C Ferries to Aucklando T Sunkist h R a r l l utuk Maraetai aw Glendowie H o Bay er W a Refer to a Glendowie T Mo G d a v e t St Thomas c a Kellys ampb e R e Glendowie t e Bay w C e n nd C n S r t ll R t a College a r l a d e r l R r R P Rd r School S ay Park d w r y d g a os Kep m o o d Beach i e e Selwyn B C ra T Central a