The Operational, Human and Policy Implications of Next Generation 9-1-1 Services in British Columbia Part One: Current State and Objectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017-18 Annual Report

Helping Canadians for 10+ YEARS 2017-18 ANNUAL REPORT “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.” – H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.”– H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.”– H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” –L.T., wireless customer in BC “I was very satisfied with the process.” – H.R., internet customer in ON “Awesome service. We are very content with the service and resolution.” – G.C., phone customer in NS “My agent was nice and super understanding” – D.W., TV customer in NB “I was very impressed with your services” – L.T., wireless customer in BC P.O. Box 56067 – Minto Place RO, Ottawa, ON K1R 7Z1 www.ccts-cprst.ca [email protected] 1-888-221-1687 TTY: 1-877-782-2384 Fax: 1-877-782-2924 CONTENTS 2017-18 -

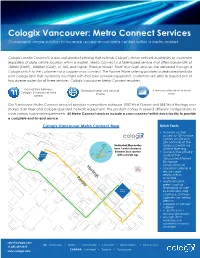

Cologix Vancouver: Metro Connect Services Convenient, Simple Solution to Increase Access Across Data Centres Within a Metro Market

Cologix Vancouver: Metro Connect Services Convenient, simple solution to increase access across data centres within a metro market Cologix’s Metro Connect is a low-cost product offering that extends Cologix’s dense network availability to customers regardless of data centre location within a market. Metro Connect is a fibre-based service that offers bandwidth of 100Mb (FastE), 1000Mb (GigE), or 10G and higher (Passive Wave). FastE and GigE services are delivered through a Cologix switch to the customer via a copper cross-connect. The Passive Wave offering provides a dedicated lambda over Cologix fibre that customers must light with their own network equipment. Customers are able to request one of two diverse routes for all three services. Cologix Vancouver Metro Connect enables: Connections between Extended carrier and network A low-cost alternative to local Cologix’s 2 Vancouver data choice loops centres Our Vancouver Metro Connect product provides connections between 1050 West Pender and 555 West Hastings over shared dark fiber and Cologix-operated network equipment. The product comes in several different confgurations to solve various customer requirements. All Metro Connect services include a cross-connect within each facility to provide a complete end-to-end service. Cologix Vancouver Metro Connect Map Quick Facts: • Network neutral access to 10+ unique carriers on-site plus 20+ networks at the Redundant bre routes ymor St. Harbour Centre via Se have 1 meter clearance diverse fibre ring 1 Meter between duct systems • Home to the primary -

Local-Level Data on Income and Poverty for BC from 2006 Census

Local-Level Data on Income and Poverty for BC from 2006 Census October 2008 This is a joint project from the Provincial Health Services Authority, Health Officers’ Council of British Columbia and Vancouver Coastal Health 1 Raymond Fang Senior Statistical Scientist Population & Public Health Provincial Health Services Authority Darryl Quantz Policy Consultant Population Health Vancouver Coastal Health Prepared for John Millar Executive Director Population Health Surveillance & Disease Control Planning Lydia Drasic Director Provincial Primary Health Care & Population Health Strategic Planning Provincial Health Services Authority Paul Martiquet Chair Health Officers’ Council of British Columbia Acknowledgement: We are grateful to Statistics Canada for releasing the 2006 Census British Columbia (table)-2007, Statistics Canada Catalogue no 92-591-XWE, Ottawa and Catalogue 97-563- XCB2006031 Provincial Health Services Authority 700-1380 Burrard Street Vancouver, BC V6Z 2H3 Canada www.phsa.ca 2 Concepts and Definitions Economic family - Refers to a group of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling and are related to each other by blood, marriage, common-law or adoption Family Income – Total income for an economic family Median Family Income – income value that 50% of families have family income higher and other 50% of families have family income lower than this value Average Family Income – average value of income of all economic families Income Inequality – the difference between average family income and median family income with a zero value indicating income is homogeneously distributed, a positive value indicating prosperity concentrates in the high income groups and a negative value indicating opposite a direction Poverty Line – also known as low-income cutoffs (LICOs): income thresholds, determined by analyzing family expenditure data, below which families will devote a larger share of income to the necessities of food, shelter and clothing than the average family would. -

CZN Comments on Final Arguments

September 16, 2011 Chuck Hubert Environmental Assessment Officer Mackenzie Valley Review Board Suite 200, 5102 50th Avenue, Yellowknife, NT X1A 2N7 Dear Mr. Hubert RE: Environmental Assessment EA0809-002, Prairie Creek Mine Comments on Final Arguments Canadian Zinc Corporation (CZN) is pleased to provide the attached comments on the Final Arguments submitted by parties at the conclusion of environmental assessment EA0809-002. Technical replies are provided, where necessary, by stating CZN’s position with respect to recommendations made. Where recommendations are unchanged from Technical Reports, the Review Board is directed to CZN’s comments on Technical Reports in Attachment 1. The contents of Attachment 1 should be read first since context is provided for some of our responses to the Final Arguments. Please note that our comments on Technical Reports contain no new information, and no timeline was provided by the Review Board for their submission. Also attached is a final commitments table (Table 1), and the curricula vitae of the main individual consultants who provided deliverables for the environmental assessment process. Yours truly, CANADIAN ZINC CORPORATION David P. Harpley, P. Geo. VP, Environment and Permitting Affairs Suite 1710-650 West Georgia Street Vancouver, BC V6B 4N9 Tel: (604) 688-2001 Fax: (604) 688-2043 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.canadianzinc.com COMMENTS ON PARTY FINAL ARGUMENTS Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) Water Management and Storage Recommendation 2: Final selection of an additional water storage option must be done in conjunction with the determination of Site Specific Water Quality Objectives for Prairie Creek. If increased capacity associated with construction of an additional pond provides for the ability to meet Reference Condition Approach benchmarks as defined within the derivation process, that option must be selected and implemented. -

NWT Transportation Report Card 2015 Is Intended to Provide a Statistical Benchmark of Progress Achieved and an Evaluation Framework to Measure Future Progress

TABLED DOCUMENT 345-17(5) TABLED ON OCTOBER 7, 2015 Table of Contents Overview ....................................................................................................................................3 Strengthening Connections .....................................................................................................5 Capturing Opportunities ...........................................................................................................9 Embracing Innovation ............................................................................................................ 11 Metrics & Data .........................................................................................................................13 1.0 Financial .................................................................................................................. 13 1.1 Capital and O&M Expenditures and Revenue .............................................. 13 1.2 Analysis of Capital Needs ............................................................................ 14 1.3 Major Partnership Funding ........................................................................... 15 1.4 Airport, Road Licensing and Deh Cho Bridge Toll Revenues ....................... 16 1.5 Northern, Local, Other, contracts and Total Value of Contracts .................... 18 1.6 Community Access Program Expenditures ................................................. 18 2.0 Airports ....................................................................................................................19 -

Spring/Summer Newsletter 2019

FREE Take One NEWS Spring/Summer 2019 Our Vision “Self reliant Indigenous people thriving in diverse economies” Exchanging Ideas and Growing Together: 2019 Annual Stakeholders Gathering April 24 marked the occasion of Pathways to Technology’s 2019 members talked about opportunities and challenges inherent annual gathering of stakeholders. Representatives from All in the ambitious Connected Coast project. The benefits are Nations Trust Company and the Pathways team spent the day innumerable, but the challenges are significant and include collaborating and exchanging ideas with representatives from issues like affordability, establishing connections to homes and First Nations Emergency Services Society, Write to Read, First buildings once the fibre backbone is in place, and the time- Nations Technology Council, First Nations Health Authority, consuming process of establishing the “passive infrastructure,” Network BC, the Ministry of Indigenous Relations and (such as land and access agreements and other administrative Reconciliation, Indigenous Services Canada, Nuu-Chah-Nulth matters), required to enable the project. Economic Development Corporation, Conuma Cable, TELUS, CityWest, and Strathcona Regional District. TELUS’ Aurora Sekela and PTT’s Thant Nyo presented next and provided a brief case study on the challenges of connecting Musqueam Elder Shane Pointe opened the session with a Penelakut Island. Lessons learned include the importance of welcome and a prayer. During this, attendees held hands with engaging communities early on to identify and solve logistical one-another and reflected on Pointe’s observation that, in the issues that can otherwise cause delays, and of streamlining past, “pathways” were the means by which people would get internal processes to maximize efficiency. -

SCHEDULE H – SERVICE DESCRIPTIONS 1. in Accordance with the Agreement, TELUS Will As of the Effective Date Make Available to T

SCHEDULE H – SERVICE DESCRIPTIONS 1. In accordance with the Agreement, TELUS will as of the Effective Date make available to the GPS Entities the Available Services described in the following Attachments to this Schedule H: a) Attachment H1 - Long Distance Services; i) Attachment H1-A – Outbound Long Distance Services; ii) Attachment H1-B – Calling Card Services; and iii) Attachment H1-C – Toll-Free Services; b) Attachment H2 – Conferencing Services; i) Attachment H2-A - Reservation-less Conferencing Services; ii) Attachment H2-B - Operator Assisted Conferencing Services; iii) Attachment H2-C - Event Conferencing Services; iv) Attachment H2-D - Web Conferencing Services; and v) Attachment H2-E – Crisis Management Conferencing Services; c) Attachment H3 – Voice Services; i) Attachment H3-A – Hosted Telephony Services; ii) Attachment H3-B – Exchange Services; and iii) Attachment H3-C - Hosted IVR Services; d) Attachment H5 – Data Services; i) Attachment H5-A – Initial Data Services ii) Attachment H5-B – Internet and Security Services; iii) Attachment H5-C – Optical Ethernet Service; and iv) Attachment H5-E – STS WAN L3 VPN Services; and e) Attachment H9 – Cellular Services; i) Attachment H9-A – Standard Cellular Services; and ii) Attachment H9-B – iDEN Network (Mike) Services; and f) Attachment H10 – Hardware and Software Procurement Services. 1 Telecommunications Services Master Agreement 2. TELUS will provide the Available Services described in the Attachments to this Schedule if and when requested by a GPS Entity pursuant to a Service Order or Service Change Order, subject to section 7.4.3 of the main body of this Agreement, in each case entered into in accordance with the terms of this Agreement, for the applicable Fees as set out in the Price Book and/or, subject to section 1.3.3 of the main body of this Agreement, the applicable Service Order or Service Change Order and as such Available Services are delivered in accordance with the terms of the Agreement including, without limitation, the Service Levels for such Services. -

Guide to The

DEASE TELEGRAPH LAKE CREEK ISKUT Bob 1. Regional District of Kitimat-Stikine Quinn Lake BRITISH Suite 300, 4545 Lazelle Avenue COLUMBIA Guide to the Terrace, BC, V8G 4E1 Meziadin Junction Stewart 250-615-6100 Cranberry Junction Nass Camp New Aiyansh Hazelton www.rdks.bc.ca Gitwinksihlkw Kitwanga Greenville Rosswood Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert 2. Northern Health Houston Kitimat Prince Suite 600, 299 Victoria Street George STIKINE Prince George, BC, V2L 5B8 250-565-2649 www.northernhealth.ca 3. School District 87 PO Box 190, Lot 5 Commercial Drive Dease Lake, BC, V0C 1L0 250-771-4440 Vancouver www.sd87.bc.ca 4. Tahltan Central Government PO Box 69, Tatl’ah Dease Lake, BC, V0C 1L0 250-771-3274 www.tahltan.org 5. Northern Lights College PO Box 220, Lot 10 Commercial Drive Dease Lake, BC, V0C 1L0 250-771-5500 www.nlc.bc.ca Produced by the Regional District of Kitimat-Stikine COMUNITY CONTACTS in collaboration with the Tahltan Central Government. 2016 Overview TOP EVENTS Located in the picturesque northwest BC, the Stikine region is home to several communities rich in Talhtan First Nations history including Dease Lake, Telegraph Creek, and Iskut. Just 236 kilometers south of the Yukon border, Dease Lake offers access to some 1 Dease Lake Fish Derby – “BC’s Largest Northern Lake Trout Derby” of Canada’s largest natural parks, Spatsizi Wilderness Park and Mount Edziza Park. Discover remote wilderness in the Stikine region 2 4on4 Industry Hockey Tournament with endless recreation opportunities from guided horseback riding in the summer months to cross country skiing in the winter. -

Northwest Transmission Line Project: Skii Km Lax Ha Traditional Use and Knowledge Report

Northwest Transmission Line Project: Skii km Lax Ha Traditional Use and Knowledge Report Prepared By: Updated December 2009 Rescan™ Environmental Services Ltd. TM Vancouver, British Columbia NORTHWEST TRANSMISSION LINE PROJECT Skii Km Lax Ha Traditional Knowledge and Use Study Executive Summary Executive Summary The purpose of this report is to inventory and describe Skii km Lax Ha Traditional Use (TU) and Traditional Knowledge (TK) related to the proposed Northwest Transmission Line (NTL) Project (the Project). Skii km Lax Ha TU/TK was collected between February and November 2007. Work was then suspended when, on November 26, 2007, NovaGold Resources Inc. and Teck Cominco Limited announced a decision to suspend construction of the Galore Creek mine project. As a result of the loss of this main customer, the Province and British Columbia Transmission Corporation (BCTC) suspended the Project for a year. In November 2008, the Province provided a mandate and additional funding to complete the Environmental Assessment. Work then recommenced and discussions about capacity funding and further data were collected between January and September 2009. A mixed methods approach was used to collect TU/TK information from April to September 2009, including desk-based archival research, direct discussions, and two formal interview sessions and mapping sessions. The key findings are summarized in the report, which indicates that the Project study area was, and to a large extent continues to be, well-travelled and frequently used by the Skii km Lax Ha, whose traditional territories intersect the Project from Cranberry River to Ningunsaw Pass (Laxyiip). Skii km Lax Ha traditional activities involve hunting, trapping, and fishing; important areas include historic and berry/plant/mushroom harvesting sites. -

EA1415-01 Developer's Assessment Report

DEVELOPER’S ASSESSMENT REPORT ALL SEASON ROAD PROJECT PRAIRIE CREEK MINE MAIN REPORT Volume 1 of 3 SUBMITTED IN SUPPORT OF: Environmental Assessment of Prairie Creek Mine EA 1415-01 SUBMITTED TO: Mackenzie Valley Review Board Yellowknife, NT X1A 2N7 SUBMITTED BY: Canadian Zinc Corporation Vancouver, BC V6B 4N9 April 2015 PROJECT FACT SHEET CORPORATE DATA Project Name Prairie Creek Mine Company Name and Address Canadian Zinc Corporation Suite 1710, 650 West Georgia Street Vancouver, B.C., V6B 4N9 Telephone: (604) 688-2001 Fax: (604) 688-2043 Canadian Zinc Corporation 9926-101st Avenue PO Box 500 Fort Simpson, NT X0E 0N0 Telephone: (867) 695-3963 Fax: (867) 695-3964 Contacts Alan Taylor, Chief Operating Officer and VP Exploration David Harpley, VP Environment & Permitting Affairs Wilbert Antoine, Manager of Northern Development COMMUNITY DATA First Nation Territory Nahanni Butte Dene Band, Dehcho Nearest Community Nahanni Butte, 95 km south-east Other Communities Fort Liard, 165 km south-east Fort Simpson, 185 km east Land Claims Status In negotiation, Dehcho Process PROJECT DETAILS Location 550 km west of Yellowknife, NWT 61°33’ N latitude, 124°48’ W longitude Undertaking ~185 km all season road to the Liard Highway essentially using the existing, permitted winter road alignment Prairie Creek All Season Road Project – April 2015 1 GONDI AEK’ÉHZE ADLÁ Gondi Éhgonñæá Dii Prairie Creek Mine góhts’edi tå’a Góhdli Ndehé k’eh yunahnee tå’uh nît’i ii gots’ç xôh shíhtah á goæô. Káa azhô t’áh Canadian Zinc Corporation (CZN) gots’êh á agøht’e. K’õô 1980 kéhonñdhe ekúh á ndéh gozhíhe gots’êh satsõ kázhe gha seegúdlá agøht’e t’áh t’ahsíi met’áh alaeda thela á agøht’e. -

22-A 2012 Social Baseline Report

APPENDIX 22-A 2012 SOCIAL BASELINE REPORT TM Seabridge Gold Inc. KSM PROJECT 2012 Social Baseline Report Rescan™ Environmental Services Ltd. Rescan Building, Sixth Floor - 1111 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6E 2J3 January 2013 Tel: (604) 689-9460 Fax: (604) 687-4277 Executive Summary Seabridge Gold Inc. is proposing to develop the KSM Project (the Project), a gold, copper, silver, and molybdenum mine located in northwestern British Columbia. The proposed Project is approximately 950 km northwest of Vancouver and 65 km northwest of Stewart, within 30 km of the British Columbia–Alaska border (Figure 1.2-1). The estimated initial capital cost of the Project is US$5.3 billion. The Project is split between two geographical areas: the Mine Site and Processing and Tailing Management Area (PTMA), connected by twin 23-km tunnels (Mitchell-Treaty Twinned Tunnels; Figure 1.2-2). The Mine Site will be located south of the closed Eskay Creek Mine, within the Mitchell Creek, McTagg Creek, and Sulphurets Creek valleys. Sulphurets Creek is a main tributary of the Unuk River, which flows to the Pacific Ocean. The PTMA will be located in the upper tributaries of Teigen and Treaty creeks. Both creeks are tributaries of the Bell-Irving River, which flows into the Nass River and Pacific Ocean. The PTMA is located about 19 km southwest of Bell II on Highway 37. This social baseline report presents a comprehensive overview of the past and present social environment and context of the proposed Project, including patterns, trends, and changes over time. It outlines relevant social factors for which data on communities in the Project area are available, such as society and governance; population and demographics; education, skills and training (level of achievement, elementary, secondary, post-secondary, and adult education); health and social services (facilities, services, trends, and issues); recreation; protection services (crime index, police, fire, and ambulance); and infrastructure (utilities, communications, transportation, and housing). -

MANAGEMENT PLAN November 2003

MANAGEMENT PLAN November 2003 for Stikine Country Protected Areas Mount Edziza Provincial Park Mount Edziza Protected Area (Proposed) Stikine River Provincial Park Spatsizi Plateau Wilderness Provincial Park Gladys Lake Ecological Reserve Ministry of Water, Land Pitman River Protected Area and Air Protection Environmental Stewardship Chukachida Protected Area Division Skeena Region Tatlatui Provincial Park Stikine Country Protected Areas M ANAGEMENT LAN P November 2003 Prepared by Skeena Region Environmental Stewardship Division Smithers BC Stikine Country Protected Areas Management Plan National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data British Columbia. Environmental Stewardship Division. Skeena Region. Stikine Country Protected Areas management plan Cover title: Management plan for Stikine Country Protected Areas. Issued by: Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, Environmental Stewardship Division, Skeena Region. “November 2003” “Mount Edziza Provincial Park, Mount Edziza Protected Area (Proposed), Stikine River Provincial Park, Spatsizi Plateau Wilderness Provincial Park, Gladys Lake Ecological Reserve, Pitman River Protected Area, Chukachida Protected Area, Tatlatui Provincial Park”—Cover. Also available on the Internet. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-5124-8 1. Protected areas - British Columbia – Stikine Region. 2. Provincial parks and reserves - British Columbia – Stikine Region. 3. Ecosystem management - British Columbia – Stikine Region. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection.