July 1, 1994 Decision of the Perry County Common

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

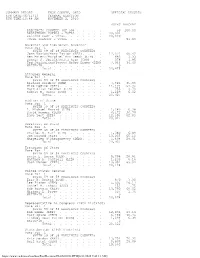

Gems Election Summary Report

Election Summary Report Date:11/23/10 Time:09:52:24 OFFICIAL BALLOT GENERAL ELECTION Page:1 of 5 NOVEMBER 2, 2010 MONTGOMERY COUNTY, OHIO OFFICIAL FINAL Registered Voters 385652 - Cards Cast 188491 48.88% Num. Report Precinct 360 - Num. Reporting 360 100.00% Governor - Lt. Governor U.S. Senator Total Total Number of Precincts 360 Number of Precincts 360 Precincts Reporting 360 100.0 % Precincts Reporting 360 100.0 % Times Counted 188491/385652 48.9 % Times Counted 188491/385652 48.9 % Total Votes 185142 Total Votes 184391 Kasich\Taylor 89218 48.19% Eric W. Deaton 2697 1.46% Matesz\Leech 4059 2.19% Lee Fisher 76441 41.46% Spisak\Rios 2397 1.29% Daniel H. LaBotz 1027 0.56% Strickland\Brown 89379 48.28% Rob Portman 102338 55.50% David L. Sargent II 3 0.00% Michael L. Pryce 1738 0.94% Write-in Votes 86 0.05% Arthur Sullivan 1 0.00% Write-in Votes 149 0.08% Attorney General Total Rep to Congress 3rd Dist. Number of Precincts 360 Total Precincts Reporting 360 100.0 % Number of Precincts 310 Times Counted 188491/385652 48.9 % Precincts Reporting 310 100.0 % Total Votes 185324 Times Counted 163241/326392 50.0 % Richard Cordray 82565 44.55% Total Votes 159290 Mike DeWine 93659 50.54% Joe Roberts 57103 35.85% Marc Allan Feldman 4341 2.34% Mike Turner 102187 64.15% Robert M. Owens 4759 2.57% Rep to Congress 8th Dist. Auditor of State Total Total Number of Precincts 52 Number of Precincts 360 Precincts Reporting 52 100.0 % Precincts Reporting 360 100.0 % Times Counted 25250/59260 42.6 % Times Counted 188491/385652 48.9 % Total Votes 24619 Total Votes 179981 John A. -

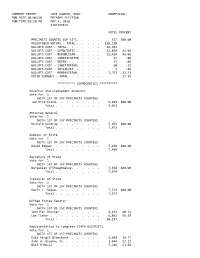

Summary Report Lake County, Ohio Unofficial Run Date:05/04/10 Primary Election Run Time:10:20 Pm May 4, 2010 Statistics

SUMMARY REPORT LAKE COUNTY, OHIO UNOFFICIAL RUN DATE:05/04/10 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:10:20 PM MAY 4, 2010 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 157). 157 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 156,210 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 26,952 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 11,058 41.03 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 12,414 46.06 BALLOTS CAST - CONSTITUTION . 17 .06 BALLOTS CAST - GREEN. 23 .09 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 60 .22 BALLOTS CAST - SOCIALIST . 7 .03 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 3,373 12.51 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 17.25 ********** (DEMOCRATIC) ********** Governor and Lieutenant Governor Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Ted Strickland. 9,021 100.00 Total . 9,021 Attorney General Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Richard Cordray . 7,973 100.00 Total . 7,973 Auditor of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) David Pepper . 7,430 100.00 Total . 7,430 Secretary of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Maryellen O'Shaughnessy. 7,874 100.00 Total . 7,874 Treasurer of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Kevin L. Boyce. 7,572 100.00 Total . 7,572 United States Senator Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Jennifer Brunner . 4,135 40.71 Lee Fisher . 6,022 59.29 Total . 10,157 Representative to Congress (14TH DISTRICT) Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Dale Virgil Blanchard . 1,658 19.77 John H. Greene, Jr. 1,444 17.22 Bill O'Neill . 5,286 63.02 Total . 8,388 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Eric Brown . -

Ohio Survey of 1,000 Likely Voters Conducted September 25, 2010 by Pulse Opinion Research for FOX News

Ohio Survey of 1,000 Likely Voters Conducted September 25, 2010 By Pulse Opinion Research for FOX News 1* If the 2010 Election for United States senate, were held today would you vote for Republican Rob Portman or Democrat Lee Fisher? 9/11/10 9/18/10 9/25/10 Rob Portman (R) 48% 49% 50% Lee Fisher (D) 41% 36% 37% Some other candidate 3% 3% 3% Not sure 8% 11% 11% Total Portman Fisher Certain 81% 81% 80% Could change mind 17% 15% 19% Not sure 3% 4% 1% 2* If the 2010 election for Ohio’s next Governor were held today, would you vote for Republican John Kasich or Democrat Ted Strickland? 9/11/10 9/18/10 9/25/10 John Kasich (R) 48% 47% 45% Ted Strickland (D) 43% 41% 43% Some other candidate 4% 2% 2% Not sure 5% 10% 10% 3* Do you approve or disapprove of the job Barack Obama is doing as president? 9/11/10 9/18/10 9/25/10 Approve 39% 38% 39% Disapprove 55% 57% 54% Not sure 6% 5% 7% 4* All in all, would you rather have bigger government that provides more services or smaller government that provides fewer services? 9/18/10 9/25/10 Bigger government that provides more services 32% 31% Smaller government that provides fewer services 59% 56% Not sure 9% 13% 5* Overall, which comes closest to your feelings about the way the federal government is working -- enthusiastic, satisfied, but not enthusiastic, dissatisfied, but not angry, or angry? 9/11/10 9/18/10 9/25/10 Enthusiastic 8% 6% 6% Satisfied but not enthusiastic 22% 22% 23% Dissatisfied but not angry 31% 36% 33% Angry 37% 35% 36% Not sure 2% 2% 2% 6* Generally speaking how would you rate the condition -

Ohio Governor's Race a Dead Heat, Quinnipiac University

Peter A. Brown Assistant Director, Quinnipiac University Polling Institute (203) 582-5201 (203) 535-6203 Rubenstein Associates, Inc. Public Relations Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: NOVEMBER 1, 2010 OHIO GOVERNOR’S RACE A DEAD HEAT, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY POLL FINDS; REPUBLICAN HAS 19-POINT LEAD IN SENATE RACE The race for Ohio governor is a dead heat with Republican John Kasich getting 47 percent of likely voters to 46 percent for Democratic incumbent Gov. Ted Strickland, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released today. In the U.S. Senate race, Republican Rob Portman has an insurmountable 56 – 37 percent lead over Democratic Lt. Gov. Lee Fisher, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University survey, conducted by live interviewers, finds. Strickland, who had trailed by double digits earlier in the fall campaign, is leading among Democrats 90 – 6 percent, but Kasich is ahead among Republicans 83 – 10 percent and independent voters 57 – 36 percent in the survey completed Saturday of those who say they are likely to vote or have already cast their ballots. Critical to the outcome are the 6 percent of likely voters who remain undecided and another 5 percent who have selected a candidate but say they could change their mind. “The governor’s race is a statistical tie. It could go either way,” said Peter A. Brown, assistant director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute. “Gov. Ted Strickland has come from far back. The question is whether he can get over the hump. He has momentum on his side. John Kasich has the historical tendency of undecided voters to break against well-known incumbents at the very end of a campaign.” Strickland is viewed favorably by 45 percent and unfavorably by the same percentage of likely voters. -

2010 General Election, Summary

SUMMARY REPORT KNOX COUNTY, OHIO OFFICIAL RESULTS RUN DATE:06/11/13 GENERAL ELECTION RUN TIME:10:44 AM NOVEMBER 2, 2010 VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 59) . 59 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 40,304 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 20,929 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 51.93 Governor and Lieutenant Governor Vote For 1 (WITH 59 OF 59 PRECINCTS COUNTED) John Kasich/Mary Taylor (REP). 12,371 60.42 Ken Matesz/Margaret Ann Leech (LIB). 682 3.33 Dennis S. Spisak/Anita Rios (GRN) . 378 1.85 Ted Strickland/Yvette McGee Brown (DEM) 7,044 34.40 WRITE-IN. 0 Total . 20,475 Attorney General Vote For 1 (WITH 59 OF 59 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Richard Cordray (DEM) . 7,320 35.83 Mike DeWine (REP). 11,123 54.45 Marc Allan Feldman (LIB) . 755 3.70 Robert M. Owens (CON) . 1,229 6.02 Total . 20,427 Auditor of State Vote For 1 (WITH 59 OF 59 PRECINCTS COUNTED) L. Michael Howard (LIB). 1,280 6.38 David Pepper (DEM) . 6,172 30.79 Dave Yost (REP) . 12,595 62.83 Total . 20,047 Secretary of State Vote For 1 (WITH 59 OF 59 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Charles R. Earl (LIB) . 1,380 6.89 Jon Husted (REP) . 13,035 65.10 Maryellen O'Shaughnessy (DEM). 5,608 28.01 Total . 20,023 Treasurer of State Vote For 1 (WITH 59 OF 59 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Kevin L. Boyce (DEM). 5,798 28.81 Matthew P. Cantrell (LIB) . 1,239 6.16 Josh Mandel (REP). 13,091 65.04 Total . 20,128 United States Senator Vote For 1 (WITH 59 OF 59 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Eric W. -

Ample Amp Mple Ample Sam Am Allo O Ball Allo Ballo Llot O T

LI-C.WAL OFFICIAL GENERAL ELECTION BALLOT NOVEMBER 2, 2010 FAIRFIELD COUNTY, OHIO Instructions to Voter 1. To vote, you must completely darken the oval ( ) at the left of the candidate or answer of your choice. 2. Do not mark the ballot for more choices than allowed. Please see permitted number of choices directly below title of office. 3. If you mark the ballot for more choices than permitted, the race or issue will not be counted. 4. To cast a write-in vote, darken the oval ( ) to the left of the line provided and write in the candidate's name. 5. If you cast a vote for a candidate whose name is printed on the ballot, do not write that candidate's name on the write-in candidate line. 6. If you make a mistake or want to change your vote, please ask an election official for a new ballot. You may ask for a new ballot up to two times. OFFICIAL OFFICE TYPE BALLOT For Auditor of State For Representative to Vote For 1 Congress (7th District) For Governor and Dave Yost Vote For 1 Lieutenant Governor Republican Bill Conner To vote for Governor and Lieutenant Democratic Governor, select the option to the left of L. Michael Howard the joint candidates of your choice. Libertarian David W. Easton Vote for 1 David Pepper Constitution For Governor Democratic JohnJohtn DD.. AndersonAnderson Dennis S. Spisak LibertarianLLibertaibertarian For Lieutenant Governor For Secretary of State Vote For 1 ootSteve Austria Anita Rios Green MaryellenMaryellen O'ShaughnessyO'Shaughneessyssy llotlloRepublican Democratic For Governor For State Senator Ted Strickland CharlesCharles RR. -

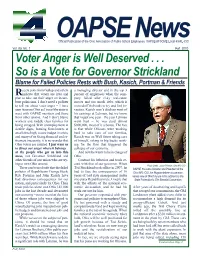

Fall 2010.Vp

OAPSEOfficial Publication of the Ohio Association of Public School EmployeesNews, OAPSE/AFSCME Local 4/AFL-CIO Vol. 69, No. 1 Fall, 2010 Voter Anger is Well Deserved . So is a Vote for Governor Strickland Blame for Failed Poli cies Rests with Bush, Kasich, Portman & Friends ecent polls from Gal lup and others a manag ing direc tor and in the top 3 Rin di cate that vot ers are irate and per cent of emplo y ees when the com- plan to take out their anger on incum - pany failed af ter risky real-es tate bent poli ti cia ns. I don’t need a pollste r moves and too much debt, which it to tell me about voter an ger – I have moved off its books to try and fool in- seen it across Ohio as I travel the state to vestors. Kasich won’t disclos e most of meet with OAPSE mem bers and those his earnings at Lehman, but we know from other unions. And I don’t blame that in just one year – the year Lehman work ers and mid dle class fami lies for went bust – he was paid alm ost be ing en raged. With un em ploy ment in $600,000, most of it a bonus. The fact dou ble dig its, hous ing foreclo sures at is that while Ohio ans were working an all-time high, a state bud get in crisis, hard to take care of our fam i lies, and many of us facing finan cia l and re - Kasich was on Wall Street tak ing care tireme nt in secu rity, it is no won der that of him self, rak ing in big bucks work - Ohio vot ers are ir ritated. -

Ohio US Senate Recap

Ohio United States Senate 2012 Josh Mandel (R) - * Sherrod Brown (D) Mandel (R) 2,435,744 44.70 % (R) Counties Won 63 *Brown (D) 2,762,766 50.70 % (D) Counties Won 25 Other 250,617 4.60% Variance (D) 327,022 6.00% Variance (R) 38 Ohio United States Senate 2010 * Rob Portman (R) - Lee Fisher (D) *Portman (R) 2,168,742 56.85 % (R) Counties Won 82 Fisher (D) 1,503,297 39.40 % (D) Counties Won 6 Other 143,059 3.75% Variance (R) 665,445 17.44% Variance (R) 76 Ohio United States Senate 2006 Mike DeWine (R) - * Sherrod Brown (D) DeWine (R) 1,761,037 43.82 % (R) Counties Won 42 *Brown (D) 2,257,369 56.16 % (D) Counties Won 46 Other 830 0.02% Variance (D) 496,332 12.35% Variance (D) 4 Ohio United States Senate 2004 * George Voinovich (R) - Eric Fingerhut (D) *Voinovich (R) 3,464,651 63.85 % (R) Counties Won 88 Fingerhut (D) 1,961,249 36.14 % (D) Counties Won 0 Other 296 0.01% Variance (R) 1,503,402 27.71% Variance (R) 88 Ohio United States Senate 2000 * Mike DeWine (R) - Ted Celeste (D) *DeWine (R) 2,666,736 59.90 % (R) Counties Won 83 Celeste (D) 1,597,122 35.87 % (D) Counties Won 5 Other 188,223 4.23% Variance (R) 1,069,614 24.03% Variance (R) 78 Ohio United States Senate 1998 * George V. Voinovich (R) - Mary Boyle (D) *Voinovich (R) 1,922,087 56.46 % (R) Counties Won 75 Boyle (D) 1,482,054 43.53 % (D) Counties Won 13 Other 210 0.01% Variance (R) 440,033 12.93% Variance (R) 62 Ohio United States Senate 1994 * Mike DeWine (R) - Joel Hyatt (D) *DeWine (R) 1,836,556 53.44 % (R) Counties Won 79 Hyatt (D) 1,348,213 39.23 % (D) Counties Won 9 Other 252,115 7.34% Variance (R) 488,343 14.21% Variance (R) 70 Ohio United States Senate 1992 Mike DeWine (R) - * John Glenn (D) DeWine (R) 2,028,300 42.31 % (R) Counties Won 48 *Glenn (D) 2,444,419 50.99 % (D) Counties Won 40 Other 321,234 6.70% Variance (D) 416,119 8.68% Variance (R) 8 Ohio United States Senate 1988 George V. -

November 7, 2006 Candidate List

NOVEMBER 7, 2006 CANDIDATE LIST Certified: May 23, 2006 Updated: September 25, 2006 DEMOCRAT REPUBLICAN GOVERNOR/LT GOVERNOR TED STRICKLAND LARRY BAYS (Write In) J KENNETH BLACKWELL 370 MARKET ST N 2444 SCHELLIN RD 693 WINDINGS LN LISBON OH 44432 WOOSTER OH 44691 CINCINNATI OH 45220 AND AND AND LEE FISHER DEBRA K FRIES THOMAS A RAGA 15925 SHAKER BLVD 2812 LEE DR 7700 BROOKFARM CT SHAKER HEIGHTS OH 44120 WOOSTER OH 44691 MASON OH 45040 JAMES LUNDEEN (Write In) 22380 OVERLOOK RD CLEVELAND HEIGHTS OH 44106 AND KEVIN J BECKER 28750 FAIRMOUNT BLVD PEPPER PIKE OH 44124 ROBERT FITRAKIS 1240 BRYDEN RD COLUMBUS OH 43205 AND ANITA RIOS 2626 ROBINWOOD TOLEDO OH 43610 WILLIAM S PEIRCE 7000 UPPER FORTY MAYFIELD VILLAGE OH 44040 AND MARK M NOBLE 723 SPRINGS DR COLUMBUS OH 43214 ATTORNEY GENERAL MARC DANN BETTY MONTGOMERY 637 NORTHLAWN DR 11133 RIVERBEND WEST CT YOUNGSTOWN OH 44505 PERRYSBURG OH 43551 AUDITOR OF STATE BARBARA SYKES MARY TAYLOR 133 FURNACE RUN DR 3431 PARFOURE BLVD AKRON OH 44307 UNIONTOWN OH 44685 SECRETARY OF STATE JENNIFER L BRUNNER JOHN A EASTMAN GREG HARTMANN 893 CHERRYFIELD AVE 6023 BUGGY WHIP LN 2560 GRANDIN RD COLUMBUS OH 43235 CENTERVILLE OH 45459 CINCINNATI OH 45208 TIMOTHY J KETTLER 29674 TWP RD 30 WARSAW OH 43844 TREASURER OF STATE RICHARD CORDRAY SANDRA O’BRIEN 4900 GROVE CITY RD 3434 STUMPVILLE RD GROVE CITY OH 43123 ROME OH 44085 U.S. SENATOR SHERROD BROWN RICHARD DUNCAN (Write In) MIKE DEWINE 37905 HERON LN 1100 EAST BLVD 2587 CONLEY RD AVON OH 44011 AURORA OH 44202 CEDARVILLE OH 45314 JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT Term -

Youngstown 2010 Citywide Plan 3

Youngstown 2010 Citywide Plan 3 GEORGE M. MCKELVEY MAYOR CITY OF YOUNGSTOWN Dr. DAVID C. SWEET PRESIDENT YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY WILLIAM D’AVIGNON DEPUTY DIRECTOR YOUNGSTOWN PLANNING DEPARTMENT HUNTER MORRISON DIRECTOR YSU CENTER FOR URBAN AND REGIONAL STUDIES JAY WILLIAMS DIRECTOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT AGENCY ANTHONY KOBAK PROJECT MANAGER 4 Youngstown 2010 Citywide Plan Lead writer: Thomas A. Finnerty Jr. Associate Director Center for Urban and Regional Studies Youngstown State University Contributors: William D’Avignon Anthony Kobak Jay Williams Urban Strategies, Inc. Copyright ©2005 by The City of Youngstown Youngstown City Hall 26 South Phelps Street Youngstown, Ohio 44503 All Rights Reserved. Layout, Design and Printing by Acknowledgments 5 Co-conveners George M. McKelvey Dr. David C. Sweet Mayor President City of Youngstown Youngstown State University Youngstown 2010 Planning Team William D’Avignon Hunter Morrison Jay Williams Tom Finnerty Anthony Kobak Jim Shanahan Youngstown City Council James Fortune, Sr. President Artis Gillam, Sr. 1st Ward Rufus Hudson 2nd Ward Richard Atkinson 3rd Ward Carol Rimedio-Righetti 4th Ward Michael Rapovy 5th Ward Paul Pancoe 6th Ward Mark Memmer 7th Ward Very special thanks to the over 5,000 community members that participated in the Youngstown Youngstown City Planning Commission Mayor George McKelvey 2010 planning process. Your involvement has Iris Guglucello made this planning process a huge success! Carmen Conglose Wallace Dunne Angelo Pignatelli Irving Lev Denise Warren Special thanks to the Youngstown 2010 working groups: Youngstown’s New Economy Youngstown’s New Neighborhoods New Image for Youngstown Youngstown Clean and Green 6 Youngstown 2010 Citywide Plan “Youngstown 2010 is not just about Youngstown’s future, it is about the future of the entire Mahoning Valley. -

It Takes a Village ... to Teach Safety

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK » TODAY’S ISSUE U DAILY BRIEFING, A2 • TRIBUTES, A7 • WORLD, A8 • BUSINESS, A10 • CLASSIFIEDS, B5 • PUZZLES, C3 KIZER RALLIES BROWNS TO WIN NEW NCAA POLICY RISING TENSIONS Rookie rolls vs. New Orleans Schools to address sex violence Trump again warns N. Korea SPORTS | B1 SPORTS | B1 DAILY BRIEFING | A2 50% OFF vouchers. SEE DETAILS, A2 FOR DAILY & BREAKING NEWS LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1869 FRIDAY, AUGUST 11, 2017 U 75¢ TRUMP: OPIOID CRISIS IS A NATIONAL EMERGENCY emergency. We’re ments to formalize the declaration President to make offi cial declaration; going to spend a lot soon. INSIDE of time, a lot of effort A drug commission convened by U The Coalition for a local offi cials hail decision, want action and a lot of money Trump and led by New Jersey Gov. Drug-Free Mahoning County Staff/wire report Local mental health and recov- on the opioid crisis,” Chris Christie recently called on the conducted its fi rst Symposium ery offi cials applaud the declaration Trump told report- president to declare a national emer- on Overdose, Grief & Healing BEDMINSTER, N.J. on Thursday. A3 President Donald Trump said and want to see it implemented as ers during a brief gency to help deal with the growing U A Warren woman who Thursday he will offi cially declare soon as possible with substantial question-and-an- Trump crisis. the opioid crisis a “national emer- investment. swer session ahead An initial report from the com- failed to cooperate with social- “The opioid crisis is an emergency. of a security briefi ng Thursday at his service agencies over her drug gency” and pledged to ramp up mission noted the approximately use was sent to jail for six government efforts to combat the And I am saying offi cially right now: golf course in Bedminster. -

Ohio Advisory Committee

Ohio Advisory Committee These business, faith, military, and community leaders believe that Ohio benefits when America leads in the world through investments in development and diplomacy. Hon. Bob Taft Hon. Lee Fisher Co-Chairs Governor Lieutenant Governor (1999-2007) (2007-2011) David Abbott John Bernloehr Eric L. Burkland The George Gund Foundation Consolidated Metal Products, Inc. Ohio Manufacturers’ Association Executive Director President President Jonathan Adams David Betras Hon. Jim Butler* SALIX Mahoning County Democratic Party Ohio House of Representatives President Chairman Member (2011-Present) Peter Ahern Dr. Bill Binning Shawn Butler Akesis Health Youngstown State University, Political Independent Contractor Chairman Science Department Hon. Capri Cafaro Professor and Chair Emeritus Dr. Suzanne Allen Ohio State Senate Philanthropy Ohio Brian Borkowski Member (2007-2016) President & CEO Assymetric Technologies John Campbell President & CEO Nicholas Anderson Executive Vice President MUSTER RDU, Inc. Barbara K. Brandt Strategic Public Partners Outreach and Business Development Barbara K. Brandt, Inc. Hon. Ted Celeste Liaison Owner Ohio House of Representatives Hon. Niraj Antani Hon. Holly Brinda Member (2007-2012) Ohio House of Representatives City of Elyria Hon. Kathleen Clyde Member (2014-Present) Mayor Portage County Dr. Ratee Apana Hon. Jamael Brown Commissioner Cincinnati Sister Cities City of Youngstown Karen Conklin President Mayor American Red Cross, Northeast Ohio George Arnold Marilyn Brown Region City of Columbus Franklin County Commissioners Executive Director, Lake to River Chapter Former Economic Development Director Board President David W. Cook Fred Arment Scott Brown Vorys, Sater, Seymour, and Pease LLP International Cities of Peace Rotary Club of Columbus Partner Executive Director Executive Director Agaytha Corbin Rabbi Ari Ballaban Dr.