University of the Witwatersrand, in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

South African tabloid newspapers’ representation of black celebrities: A social constructionism perspective Emmanuel Mogoboya Matsebatlela Dissertation presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Journalism) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Josh Ogada September 2009 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: (Emmanuel Mogoboya Matsebatlela) Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people: . My supervisor, Josh Ogada, for his expert and invaluable guidance throughout the course of my studies. Professor Alet Kruger for helping me with the translations. The University of South Africa for providing me unrestricted access to their library facilities. My parents, John and Paulina Matsebatlela, for their unwavering support and constant encouragement. My wife, Molebogeng, for her patience, motivation and support. 2 DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this study to my late Uncles, Rangwane M’phalaborwa ‘Mamodila Selemantwa’ Matsebatlela and Malome Thomas Mahlo. Though their life journeys have ended, they will forever remain etched in our memories. May their souls rest in peace. 3 ABSTRACT This study examines how positively or negatively as well as how subjectively or objectively the South African tabloid newspapers represent black celebrities. This examination was primarily conducted by using the content analysis research technique. The researcher selected a total of 85 newspapers spread across four different South African daily and weekend tabloid newspapers that were published during the period February to September 2008. -

Who Owns the News Media?

RESEARCH REPORT July 2016 WHO OWNS THE NEWS MEDIA? A study of the shareholding of South Africa’s major media companies ANALYSTS: Stuart Theobald, CFA Colin Anthony PhibionMakuwerere, CFA www.intellidex.co.za Who Owns the News Media ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We approached all of the major media companies in South Africa for assistance with information about their ownership. Many responded, and we are extremely grateful for their efforts. We also consulted with several academics regarding previous studies and are grateful to Tawana Kupe at Wits University for guidance in this regard. Finally, we are grateful to Times Media Group who provided a small budget to support the research time necessary for this project. The findings and conclusions of this project are entirely those of Intellidex. COPYRIGHT © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd This report is the intellectual property of Intellidex, but may be freely distributed and reproduced in this format without requiring permission from Intellidex. DISCLAIMER This report is based on analysis of public documents including annual reports, shareholder registers and media reports. It is also based on direct communication with the relevant companies. Intellidex believes that these sources are reliable, but makes no warranty whatsoever as to the accuracy of the data and cannot be held responsible for reliance on this data. DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS Intellidex has, or seeks to have, business relationships with the companies covered in this report. In particular, in the past year, Intellidex has undertaken work and received payment from, Times Media Group, Independent Newspapers, and Moneyweb. 2 www.intellidex.co.za © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd Who Owns the News Media CONTENTS 1. -

Blurred Lines

BLURRED LINES: HOW SOUTH AFRICA’S INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM HAS CHANGED WITH A NEW DEMOCRACY AND EVOLVING COMMUNICATION TOOLS Zoe Schaver The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Media and Journalism Advised by: __________________________ Chris Roush __________________________ Paul O’Connor __________________________ Jock Lauterer BLURRED LINES 1 ABSTRACT South Africa’s developing democracy, along with globalization and advances in technology, have created a confusing and chaotic environment for the country’s journalists. This research paper provides an overview of the history of the South African press, particularly the “alternative” press, since the early 1900s until 1994, when democracy came to South Africa. Through an in-depth analysis of the African National Congress’s relationship with the press, the commercialization of the press and new developments in technology and news accessibility over the past two decades, the paper goes on to argue that while journalists have been distracted by heated debates within the media and the government about press freedom, and while South African media companies have aggressively cut costs and focused on urban areas, the South African press has lost touch with ordinary South Africans — especially historically disadvantaged South Africans, who are still struggling and who most need representation in news coverage. BLURRED LINES 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction A. Background and Purpose B. Research Questions and Methodology C. Definitions Chapter II: Review of Literature A. History of the Alternative Press in South Africa B. Censorship of the Alternative Press under Apartheid Chapter III: Media-State Relations Post-1994 Chapter IV: Profits, the Press, and the Public Chapter V: Discussion and Conclusion BLURRED LINES 3 CHAPTER I: Introduction A. -

RATE CARD 2018 Contents

RATE CARD 2018 Contents 1. Digital Rates 2. Newspaper Rates 3. Local Titles Insert Rates 4. Magazine Rates 5. Material & Insert Deadlines 6. Column Sizes ϳ͘ dĞƌŵƐĂŶĚŽŶĚŝƟŽŶƐ 8. Contact Details ůůƌĂƚĞƐĂƌĞEĞƩĂŶĚĞdžĐůƵĚĞsd ZĂƚĞƐĞīĞĐƟǀĞƉƌŝůϮϬϭϴʹDĂƌĐŚϮϬϭϵ ĂŶĐĞůůĂƟŽŶĨĞĞǁŝůůďĞĐŚĂƌŐĞĚĨŽƌůĂƚĞĐĂŶĐĞůůĂƟŽŶƐ 1 1. Rates Digital ZĂƚĞƐĂŶĚWƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶ/ŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶMonday - Saturday Click on a heading below to navigate to that page Digital Rates Netwerk 24 City Press Son <ŝĐŬKī Ϯ͘ EĞǁƐƉĂƉĞƌ Netnuus Daily Sun Soccer Laduma Kuier Rates WƌŝŶƚZĂƚĞƐ DŽŶĚĂLJͲ&ƌŝĚĂLJ DŽŶĚĂLJͲ^ĂƚƵƌĚĂLJ Sunday Titles Daily Sun Beeld City Press Son Die Burger Rapport Volksblad Son op Sonday Volksblad 3. Tiltes Local DŽŶĚĂLJͲ&ƌŝĚĂLJtĞĚŶĞƐĚĂLJ /ŶƐĞƌƚZĂƚĞƐ The Witness & Weekend Witness Sunday Sun Soccer Laduma >ŽĐĂůdŝƚůĞƐ/ŶƐĞƌƚZĂƚĞƐ ĂƐƚĞƌŶĂƉĞdŝƚůĞƐ tĞƐƚĞƌŶĂƉĞ͗WĞŶŝŶƐƵůĂdŝƚůĞƐ Maritzburg Echo Isolomzi Express City Vision Lagunya ^ŽƵƚŚŽĂƐƚ&ĞǀĞƌ Kouga Express City Vision Khayelitsha Mid-Karoo Express >ŝŵƉŽƉŽdŝƚůĞƐ ŝƚLJsŝƐŝŽŶ>ǁĂŶĚůĞͬEŽŵnjĂŵŽ 4. Magazine Mthatha Express Rise ‘n Shine People’s Post Athlone Rates PE Express DƉƵŵĂůĂŶŐĂdŝƚůĞƐ WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚƚůĂŶƟĐ^ĞĂͲŽĂƌĚͬ Queenstown Express ŝƚLJĚŝƟŽŶ UD Express Cosmos News WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚůĂƌĞŵŽŶƚͬ Rondebosch &ƌĞĞ^ƚĂƚĞdŝƚůĞƐ EŽƌƚŚtĞƐƚdŝƚůĞƐ WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚŽŶƐƚĂŶƟĂͬtLJŶďĞƌŐ Bloemnuus ĂƌůĞƚŽŶǀŝůůĞ,ĞƌĂůĚ WĞŽƉůĞΖƐWŽƐƚ&ĂůƐĞĂLJ Midweek Potchefstroom Herald /ŶƐĞƌƚĞĂĚůŝŶĞƐ Express ϱ͘ DĂƚĞƌŝĂůΘ People's Post Grassy Park Kroonnuus Potchefstroom Herald People's Post Landsdowne Vista Leseding News Bojanala People’s Post Michell’s Plain Vrystaat Nuus EŽƌƚŚĞƌŶĂƉĞdŝƚůĞƐ People’s Post -

Public Libraries in the Free State

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Annual Report 2010 N T Ann Rrepo P

AnnualAnn RReReportpop rtt 2010 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting 2 Financial highlights 22 Review of operations 42 Governance 74 Consolidated 198 Notice of AGM 4 Group at a glance 24 Internet 51 Sustainability and company 205 Proxy form 6 Global footprInt 30 Pay television 66 Directorate annual financial 8 Chairman’s and 36 Print media 71 Administration and statements managing corporate information director’s report 72 Analysis of 16 Financial review shareholders and shareholders’ diary Entertainment at your fingertips Vision for subscribers To – wherever I am – have access to entertainment, trade opportunities, information and to my friends Naspers Annual Report 2010 1 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting Mission To develop in the leading group media and e-commerce platforms in emerging markets www.naspers.com 2 Naspers Annual Report 2010 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting kgFINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Revenue (R’bn) Ebitda (R’m) Ebitda margin (%) 28,0 6 496 23,2 26,7 6 026 22,6 09 10 09 10 09 10 Headline earnings Core HEPS Dividend per per share (rand) (rand) share (proposed) (rand) 8,84 14,26 2,35 8,27 11,79 2,07 09 10 09 10 09 10 2010 2009 R’m R’m Income statement and cash flow Revenue 27 998 26 690 Operational profit 5 447 4 940 Operating profit 4 041 3 783 Net profit attributable -

We Were Cut Off from the Comprehension of Our Surroundings

Black Peril, White Fear – Representations of Violence and Race in South Africa’s English Press, 1976-2002, and Their Influence on Public Opinion Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln vorgelegt von Christine Ullmann Institut für Völkerkunde Universität zu Köln Köln, Mai 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work presented here is the result of years of research, writing, re-writing and editing. It was a long time in the making, and may not have been completed at all had it not been for the support of a great number of people, all of whom have my deep appreciation. In particular, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Bollig, Prof. Dr. Richard Janney, Dr. Melanie Moll, Professor Keyan Tomaselli, Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, and Prof. Dr. Teun A. van Dijk for their help, encouragement, and constructive criticism. My special thanks to Dr Petr Skalník for his unflinching support and encouraging supervision, and to Mark Loftus for his proof-reading and help with all language issues. I am equally grateful to all who welcomed me to South Africa and dedicated their time, knowledge and effort to helping me. The warmth and support I received was incredible. Special thanks to the Burch family for their help settling in, and my dear friend in George for showing me the nature of determination. Finally, without the unstinting support of my two colleagues, Angelika Kitzmantel and Silke Olig, and the moral and financial backing of my family, I would surely have despaired. Thank you all for being there for me. We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. -

Naspers 2010 Sustainability Report

Naspers 2010 Sustainability report Reporting parameters and management approach This is our third sustainability report prepared in accordance with the guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). In the period under review, the group increased its focus on the potential impact on the environment as well as enhanced its reporting. Many of the aspects covered in the GRI guidelines are also included in the annual report on the Naspers corporate internet site (www.naspers.com). Our South African operations publish separate annual and sustainability reports on www.media24.co.za and www.multichoice.co.za. The reporting period is in line with the group fiscal year, being 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2010. Naspers’s view on sustainability is in line with that of the GRI and it aims to identify the areas where it can contribute most towards creating value for its shareholders. Any feedback can be communicated directly to [email protected]. Reporting scope The activities of the operations in which Naspers has management control in South Africa are included in this report, except for areas where another scope is specifically indicated. Page 1 of 47 Naspers 2010 sustainability report STRATEGY AND ANALYSIS Balancing people profit planet The Naspers group play a role in the sustainable development of South Africa. We pay taxes to government and remuneration to our employees. Socially we contribute via community involvement. We strive to protect the environment through our efforts to reduce the group impact by using sophisticated printing technologies, recycling and focusing on energy efficiency. Several broad-based black economic empowerment schemes have been introduced over the years. -

1149 Date of Publication: 27 March 2015 NA IQP Number: 9 Date of Reply: 15 April 2015

MINISTRY OF TOURISM REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Private Bag X424, Pretoria, 0001, South Africa. Tel. (+27 12) 444 6780, Fax (+27 12) 444 7027 Private Bag X9154, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa. Tel. (+27 21) 469 5800, Fax: (+27 21) 465 3216 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION FOR WRITTEN REPLY: Question Number: 1149 Date of Publication: 27 March 2015 NA IQP Number: 9 Date of Reply: 15 April 2015 Mr T W Mhlongo (DA) to ask the Minister of Tourism: (a) What amount did (i) his department and (ii) state entities reporting to him spend on each newspaper subscription in each month (aa) in the (aaa) 2011-12. (bbb) 2012-13 and (ccc) 2013-14 financial years and (bb) during the period 1 April 2014 up to the latest specified date for which information is available and (b) how many copies of each newspaper were ordered on each day of the week (i) in each specified financial year and (ii) during the period 1 April 2014 up to the latest specified date for which information is available? NW1314E REPLY: (i) (aa) (aaa) 2011-12 Financial Year NEWSPAPER COST PER MONTH Beeld R 338.26 Pretoria News R 698.46 Sowetan R 489.30 Business Day R2700.40 Mail and Guardian R1085.24 The Times Magazine R 212.28 1 Die Burger R 367.95 Cape Times R 459.61 Cape Argus R 367.95 Sunday Argus R 130.24 Saturday Argus R 130.24 Sunday Times R 868.42 Sunday World R 156.00 Sunday Independent R 421.99 City Press R 284.97 Rapport R 284.97 The New Age R 211.75 Daily Sun R 76.49 Saturday Star R 174.62 Citizen R 50.08 The Star R 218.27 Financial Mail R 202.63 Economist R 269.98 Newsweek R 83.62 Foreign -

How Die Burger Newspaper Developed from Print to Digital Within a Century

How Die Burger Newspaper developed from print to digital within a century On the 18th of December 1914 in a Victorian style house named Heemstede, sixteen South African citizens established De Nationale Pers Beperkt better known as Naspers and Media24 today. This leads to the creating of the first edition of De Burger Newspaper on the 26th of July 1915. On the 12th of May 1915 De Nationale Pers Beperkt in Cape Town was registered under the Maatschappijenwet of 1892. The “Akte van Oprichting” were compiled at 22 Wale Street and Keeromstraat 30 became Naspers’ first address. Die Burger Newspaper was since its origin on 26 July 1915 a non profitable company. In 1928 the distribution of dividends became a reality. Willie Hofmeyr managed Naspers and established Santam and Sanlam in 1918 Today Media24 News publishes more than 90 titles and about 294,6 Million newspapers annually The weekly urban Newspapers have a strong market penetration and a circulation of about 974 000 per week, while the community newspapers’ circulation amounts to about 2 million a week. Naspers currently have 22031976 unique browsers over 90 newspapers and 60 magazines. Paul Jones, circulation manager confirms that Die Burger currently supply newspaper copies to 95 libraries in the WC and EC. We also working with the SBA we annually send 60,000 newspapers to 209 schools in the Western Cape. Our “ Leer en Presteer” appendix has recently ended in the Eastern Cape and we have distributed 24,000 newspapers to schools in the Eastern Cape . Preservation Each month the original copies of Die Burger were combined into bundles and covered with hard covers by the National Library of Southern Africa in Cape Town. -

RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011

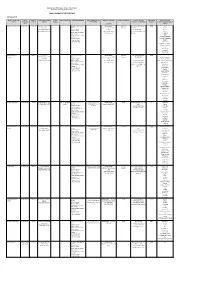

2011 RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011 Beeld (Mon, Tues) Beeld (Wed, Thurs, Fri) BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Beeld Main Body R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Beeld Main Body R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sport 24 R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Sport 24 R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 BEELD BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Jip R127.00 R172.50 R172.50 R172.50 Leefstyl R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Buite Beeld R146.10 R201.60 R201.60 R201.60 Motors R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Vrydag R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 BEELD Oos Beeld R 46.10 R 64.80 R 64.80 R 64.80 Tshwane Beeld R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Mpumalanga Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Noordwes Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Wes Beeld R 40.90 R 54.60 R 54.60 R 54.60 Huisgids R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Die Burger (Mon, Tues) Die Burger (Wed, Thurs, Fri) DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Burger Wes Main Body R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Main Body R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Promosies R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Promosies R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sport 24 R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Sport 24 R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Jip Wes R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Leefstyl -

SA Media SA Media Is an Exclusive News Research Tool Offering Press Clippings for Researchers in Academic, Government and Corporate Markets

SA Media SA Media is an exclusive news research tool offering press clippings for researchers in academic, government and corporate markets. This product offers full-text coverage of the major South African news media. The SA Media service is unique in that it offers a press clipping service covering 39 of the mainstream publications in South Africa from 1978 to date. At the moment, we have over 4,5 million news articles in the archive, a number that will grow by about 2500 selected news articles per week. The selection is based on specific subjects. When you subscribe annually to this service, you can be sure that you have one of the most comprehensive tools available when searching in all mainstream local publications on any topic. All the articles are full text and every word in every article is searchable. We have recently started adding all the images and photographs in full colour to give you the original article for your research. You can search an array of newspaper sources and download them in PDF format for easy printing and archiving. Currently we cover 19 daily publications, 17 weekend publications, two weekly publications and one monthly publication. Sabinet’s in-house Digitisation department scans and indexes the selected articles daily. Here is a list of the SA news sources we have available. BEELD FINANCIAL MAIL SUNDAY ARGUS BURGER MAIL AND GUARDIAN SUNDAY INDEPENDENT BUSINESS DAY PRETORIA NEWS SUNDAY SUN CAPE ARGUS PRETORIA NEWS WEEKEND SUNDAY TIMES AND TIME CAPE TIMES RAPPORT SUNDAY TRIBUNE CITIZEN SATURDAY ARGUS SUNDAY WORLD CITIZEN SATURDAY SATURDAY BEELD THE EP HERALD CITY PRESS SATURDAY DISPATCH THE NEW AGE DAILY DISPATCH SATURDAY INDEPENDENT THE TIMES DAILY NEWS SATURDAY STAR VOLKSBLAD DAILY SUN SATURDAY VOLKSBLAD WEEKEND POST DIAMOND FIELDS ADVERTISER SOWETAN WEEKEND WITNESS DITSEM VRYSTAAT STAR NATAL WITNESS Please note: There is a four week delay between the newspaper publication dates and the date on which the articles from these newspapers are loaded into SA Media.