Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Restoration of Tulbagh As Cultural Signifier

BETWEEN MEMORY AND HISTORY: THE RESTORATION OF TULBAGH AS CULTURAL SIGNIFIER Town Cape of A 60-creditUniversity dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in the Conservation of the Built Environment. Jayson Augustyn-Clark (CLRJAS001) University of Cape Town / June 2017 Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment: School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ‘A measure of civilization’ Let us always remember that our historical buildings are not only big tourist attractions… more than just tradition…these buildings are a visible, tangible history. These buildings are an important indication of our level of civilisation and a convincing proof for a judgmental critical world - that for more than 300 years a structured and proper Western civilisation has flourished and exist here at the southern point of Africa. The visible tracks of our cultural heritage are our historic buildings…they are undoubtedly the deeds to the land we love and which God in his mercy gave to us. 1 2 Fig.1. Front cover – The reconstructed splendour of Church Street boasts seven gabled houses in a row along its western side. The author’s house (House 24, Tulbagh Country Guest House) is behind the tree (photo by Norman Collins). -

Table of Contents

South African tabloid newspapers’ representation of black celebrities: A social constructionism perspective Emmanuel Mogoboya Matsebatlela Dissertation presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Journalism) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Josh Ogada September 2009 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: (Emmanuel Mogoboya Matsebatlela) Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people: . My supervisor, Josh Ogada, for his expert and invaluable guidance throughout the course of my studies. Professor Alet Kruger for helping me with the translations. The University of South Africa for providing me unrestricted access to their library facilities. My parents, John and Paulina Matsebatlela, for their unwavering support and constant encouragement. My wife, Molebogeng, for her patience, motivation and support. 2 DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this study to my late Uncles, Rangwane M’phalaborwa ‘Mamodila Selemantwa’ Matsebatlela and Malome Thomas Mahlo. Though their life journeys have ended, they will forever remain etched in our memories. May their souls rest in peace. 3 ABSTRACT This study examines how positively or negatively as well as how subjectively or objectively the South African tabloid newspapers represent black celebrities. This examination was primarily conducted by using the content analysis research technique. The researcher selected a total of 85 newspapers spread across four different South African daily and weekend tabloid newspapers that were published during the period February to September 2008. -

Who Owns the News Media?

RESEARCH REPORT July 2016 WHO OWNS THE NEWS MEDIA? A study of the shareholding of South Africa’s major media companies ANALYSTS: Stuart Theobald, CFA Colin Anthony PhibionMakuwerere, CFA www.intellidex.co.za Who Owns the News Media ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We approached all of the major media companies in South Africa for assistance with information about their ownership. Many responded, and we are extremely grateful for their efforts. We also consulted with several academics regarding previous studies and are grateful to Tawana Kupe at Wits University for guidance in this regard. Finally, we are grateful to Times Media Group who provided a small budget to support the research time necessary for this project. The findings and conclusions of this project are entirely those of Intellidex. COPYRIGHT © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd This report is the intellectual property of Intellidex, but may be freely distributed and reproduced in this format without requiring permission from Intellidex. DISCLAIMER This report is based on analysis of public documents including annual reports, shareholder registers and media reports. It is also based on direct communication with the relevant companies. Intellidex believes that these sources are reliable, but makes no warranty whatsoever as to the accuracy of the data and cannot be held responsible for reliance on this data. DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS Intellidex has, or seeks to have, business relationships with the companies covered in this report. In particular, in the past year, Intellidex has undertaken work and received payment from, Times Media Group, Independent Newspapers, and Moneyweb. 2 www.intellidex.co.za © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd Who Owns the News Media CONTENTS 1. -

Blurred Lines

BLURRED LINES: HOW SOUTH AFRICA’S INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM HAS CHANGED WITH A NEW DEMOCRACY AND EVOLVING COMMUNICATION TOOLS Zoe Schaver The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Media and Journalism Advised by: __________________________ Chris Roush __________________________ Paul O’Connor __________________________ Jock Lauterer BLURRED LINES 1 ABSTRACT South Africa’s developing democracy, along with globalization and advances in technology, have created a confusing and chaotic environment for the country’s journalists. This research paper provides an overview of the history of the South African press, particularly the “alternative” press, since the early 1900s until 1994, when democracy came to South Africa. Through an in-depth analysis of the African National Congress’s relationship with the press, the commercialization of the press and new developments in technology and news accessibility over the past two decades, the paper goes on to argue that while journalists have been distracted by heated debates within the media and the government about press freedom, and while South African media companies have aggressively cut costs and focused on urban areas, the South African press has lost touch with ordinary South Africans — especially historically disadvantaged South Africans, who are still struggling and who most need representation in news coverage. BLURRED LINES 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Introduction A. Background and Purpose B. Research Questions and Methodology C. Definitions Chapter II: Review of Literature A. History of the Alternative Press in South Africa B. Censorship of the Alternative Press under Apartheid Chapter III: Media-State Relations Post-1994 Chapter IV: Profits, the Press, and the Public Chapter V: Discussion and Conclusion BLURRED LINES 3 CHAPTER I: Introduction A. -

An Ageing Anachronism: D.F. Malan As Prime Minister, 1948–1954

An Ageing Anachronism: D.F. Malan as Prime Minister, 1948–1954 LINDIE KOORTS Department of Historical Studies, University of Johannesburg This article tells the behind-the-scenes tale of the first apartheid Cabinet under Dr D.F. Malan. Based on the utilisation of prominent Nationalists’ private documents, it traces an ageing Malan’s response to a changing international context, the chal- lenge to his leadership by a younger generation of Afrikaner nationalists and the early, haphazard implementation of the apartheid policy. In order to safeguard South Africa against sanctions by an increasingly hostile United Nations, Malan sought America’s friendship by participating in the Korean War and British protection in the Security Council by maintaining South Africa’s Commonwealth membership. In the face of decolonisation, Malan sought to uphold the Commonwealth as the preserve of white-ruled states. This not only caused an outcry in Britain, but it also brought about a backlash within his own party. The National Party’s republican wing, led by J.G. Strijdom, was adamant that South Africa should be a republic outside the Commonwealth. This led to numerous clashes in the Cabinet and parliamentary caucus. Malan and his Cabinet’s energies were consumed by these internecine battles. The systematisation of the apartheid policy and the coordination of its implementation received little attention. Malan’s disengaged leadership style implies that he knew little of the inner workings of the various government departments for which he, as Prime Minister, was ultimately responsible. The Cabinet’s internal disputes about South Africa’s constitutional status and the removal of the Coloured franchise ultimately served as lightning conductors for a larger issue: the battle for the party’s leadership, which came to a head in 1954. -

RATE CARD 2018 Contents

RATE CARD 2018 Contents 1. Digital Rates 2. Newspaper Rates 3. Local Titles Insert Rates 4. Magazine Rates 5. Material & Insert Deadlines 6. Column Sizes ϳ͘ dĞƌŵƐĂŶĚŽŶĚŝƟŽŶƐ 8. Contact Details ůůƌĂƚĞƐĂƌĞEĞƩĂŶĚĞdžĐůƵĚĞsd ZĂƚĞƐĞīĞĐƟǀĞƉƌŝůϮϬϭϴʹDĂƌĐŚϮϬϭϵ ĂŶĐĞůůĂƟŽŶĨĞĞǁŝůůďĞĐŚĂƌŐĞĚĨŽƌůĂƚĞĐĂŶĐĞůůĂƟŽŶƐ 1 1. Rates Digital ZĂƚĞƐĂŶĚWƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶ/ŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶMonday - Saturday Click on a heading below to navigate to that page Digital Rates Netwerk 24 City Press Son <ŝĐŬKī Ϯ͘ EĞǁƐƉĂƉĞƌ Netnuus Daily Sun Soccer Laduma Kuier Rates WƌŝŶƚZĂƚĞƐ DŽŶĚĂLJͲ&ƌŝĚĂLJ DŽŶĚĂLJͲ^ĂƚƵƌĚĂLJ Sunday Titles Daily Sun Beeld City Press Son Die Burger Rapport Volksblad Son op Sonday Volksblad 3. Tiltes Local DŽŶĚĂLJͲ&ƌŝĚĂLJtĞĚŶĞƐĚĂLJ /ŶƐĞƌƚZĂƚĞƐ The Witness & Weekend Witness Sunday Sun Soccer Laduma >ŽĐĂůdŝƚůĞƐ/ŶƐĞƌƚZĂƚĞƐ ĂƐƚĞƌŶĂƉĞdŝƚůĞƐ tĞƐƚĞƌŶĂƉĞ͗WĞŶŝŶƐƵůĂdŝƚůĞƐ Maritzburg Echo Isolomzi Express City Vision Lagunya ^ŽƵƚŚŽĂƐƚ&ĞǀĞƌ Kouga Express City Vision Khayelitsha Mid-Karoo Express >ŝŵƉŽƉŽdŝƚůĞƐ ŝƚLJsŝƐŝŽŶ>ǁĂŶĚůĞͬEŽŵnjĂŵŽ 4. Magazine Mthatha Express Rise ‘n Shine People’s Post Athlone Rates PE Express DƉƵŵĂůĂŶŐĂdŝƚůĞƐ WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚƚůĂŶƟĐ^ĞĂͲŽĂƌĚͬ Queenstown Express ŝƚLJĚŝƟŽŶ UD Express Cosmos News WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚůĂƌĞŵŽŶƚͬ Rondebosch &ƌĞĞ^ƚĂƚĞdŝƚůĞƐ EŽƌƚŚtĞƐƚdŝƚůĞƐ WĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐWŽƐƚŽŶƐƚĂŶƟĂͬtLJŶďĞƌŐ Bloemnuus ĂƌůĞƚŽŶǀŝůůĞ,ĞƌĂůĚ WĞŽƉůĞΖƐWŽƐƚ&ĂůƐĞĂLJ Midweek Potchefstroom Herald /ŶƐĞƌƚĞĂĚůŝŶĞƐ Express ϱ͘ DĂƚĞƌŝĂůΘ People's Post Grassy Park Kroonnuus Potchefstroom Herald People's Post Landsdowne Vista Leseding News Bojanala People’s Post Michell’s Plain Vrystaat Nuus EŽƌƚŚĞƌŶĂƉĞdŝƚůĞƐ People’s Post -

LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS 2 No

Vol. 651 Pretoria 20 September 2019 , September No. 42714 ( PART1 OF 2 ) LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS 2 No. 42714 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 20 SEPTEMBER 2019 STAATSKOERANT, 20 SEPTEMBER 2019 No. 42714 3 Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Eastern Cape / Oos-Kaap ................................................................................................................. 14 Free State / Vrystaat ........................................................................................................................ 15 Limpopo ....................................................................................................................................... 15 North West / Noordwes ..................................................................................................................... 15 Western Cape / Wes-Kaap ................................................................................................................ 15 COMPANY NOTICES • MAATSKAPPYKENNISGEWINGS Western Cape / Wes-Kaap ................................................................................................................ 16 LIQUIDATOR’S AND OTHER APPOINTEES’ NOTICES LIKWIDATEURS EN ANDER AANGESTELDES SE KENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ...................................................................................................................................... -

Psychological Responses to Coverage of Crime in the Beeld Newspaper

Psychological Responses to Coverage of Crime in the Beeld Newspaper Talia Thompson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Clinical Psychology). Declaration I declare that this dissertation is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the Degree of Masters of Arts (Clinical Psychology) at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at any other University. _____________ Talia Thompson ______ day of _______ 2009. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Gill Eagle, for her thoughtful input and patient guidance throughout the process of writing up this study. Her support, knowledge and commitment to encouraging excellence significantly contributed to making this research process challenging and meaningful. I would like to express sincere gratitude to my husband, Coenie, for his immeasurable generosity and support throughout all my studies. His patient encouragement is deeply appreciated and treasured. I would like to thank my parents and my brother for their support, encouragement and interest in this study. I had the privilege of studying with a very special group of people in the last couple of years and I would like to thank this group in particular for all their warm support and encouragement. Lastly, I would like to thank the participants who volunteered their time to reflect thoughtfully and honestly on the impact of coverage of crime in the Beeld newspaper. iii Abstract This research study aimed to explore the psychological impact of coverage of crime in the Beeld newspaper. -

Public Libraries in the Free State

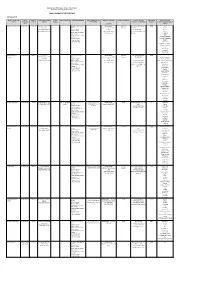

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Politics and the Media in Southern Africa I

Politics and the Media in Southern Africa I. Media and Politics: The Role of the Media in Promoting Democracy and Good Governance 21–23 September 1999 Safari Court Hotel Windhoek, Namibia II. Konrad Adenauer Foundation Journalism Workshop: the Media in Southern Africa 10–12 September 1999 River Side Hotel Durban, South Africa Table of Contents Introduction 5 I. MEDIA AND POLITICS: THE ROLE OF THE MEDIA IN PROMOTING DEMOCRACY AND GOOD GOVERNANCE Opening Remarks 9 Michael Schlicht, Regional Representative, Central and Southern Africa, Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAF) Opening Address 11 Ben Amathila, Minister of Information and Broadcasting, Namibia Obstacles and Challenges Facing the Media in: • KENYA 15 Henry Owuor, Nation Newspapers, Nairobi • MALAWI 17 Peter Kumwenda, Editor, The Champion, Lilongwe • SOUTH AFRICA 21 Xolisa Vapi, Political Reporter, The Independent on Saturday, Durban • TANZANIA 27 Matilda Kasanga, The Guardian Limited, Dar-es-Salaam • UGANDA 33 Tom Gawaya-Tegulle, The New Vision, Kampala • ZAMBIA 41 Masautso Phiri, Zambia Independent Media Association, Lusaka • ZIMBABWE 53 Davison S. Maruziva, The Daily News, Harare The Media and Ethics 55 Pushpa A. Jamieson, The Chronicle, Lilongwe, Malawi 3 Table of Contents The Media and Elections 59 Raymond Louw, Editor and Publisher, Southern Africa Report Investigative Journalism: the Police Perspective 65 Martin S. Simbi, Principal, Police Staff College, Zimbabwe Republic Police Seminar Programme 69 Seminar Participants’ List 71 II. KONRAD ADENAUER FOUNDATION JOURNALISM WORKSHOP: -

A Case Study of the Natal Witness

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF THE NATAL WITNESS by MARYLAWHON Submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of Master in Environment and Development in the Centre for Environment and Development, School ofApplied Environmental Sciences University ofKwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg 2004 ABSTRACT The media has had a significant impact on spreading environmental awareness internationally. The issues covered in the media can be seen as both representative of and an influence upon the heterogeneous public. This paper describes the environmental reporting in the South African provincial newspaper, the Natal Witness, and considers the results to both represent and influence South African environmental ideology. Environmental reporting In South Africa has been criticised for its focus on 'green' environmental issues. This criticism is rooted in the traditionally elite nature of both the media and environmentalists. However, both the media and environmentalists have been noted to be undergoing transformation. This research tests the veracity of assertions that environmental reporting is elitist, and has found that the assertions accurately describe reporting in the Witness. 'Green' themes are most commonly found, and sources and actors tend to be white and men. However, a broad range of discourses were noted, showing that the paper gives voice to a range of ideologies. These results hopefully will make a positive contribution to the environmental field by initiating debate, further studies, and reflection on the part of environmentalists, journalists, and academics on the relationship between the media and the South African environment. The work described in this dissertation was carried in the Centre for Environment and Development, University ofKwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, from July 2004 to December 2004, under the supervision ofProfessor Robert Fincham. -

A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo W Introduction and Summary of Lessons

Witness Apartheid: A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo w Introduction and Summary of Lessons . 3 Day One: Apartheid Simulation . ?C Day 'bo: Film-Witness to Apartheid . 7 Day Three: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" . 9 Day Four: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" (completion) . 11 Day Five: South Africa Letter Writing. 13 Reference Materials . 14 Additional Reading Suggestions for Student. Reading Suggestions for lkachers Additional Film Suggestions Student Handout #1 Privileged Minority. .......................... 15 Student Handout #2 The Bantustans . 16 Student Handout #3 Human Rights Fact Sheet. 17 Student Handout #4 Learning Was Defiance . 19 Student Handout #5 South African Student . 21 Student Handout #6 Challenging "Gutter Education". 23 a1987 Copyright by William Bigelow Published by The Southern Africa Media Center California Newsreel, 630 Natoma Street, San Francisco, CA 94103, (415) 621-6196 This "Raching Guide" made possible by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Design, typesetting, and production by Allogmph, San Francisco Film, Witness to Apartheid (classroom version): 35 minutes, 1986 Produced and directed by Sharon Sopher Co-produced by Kevin Harris Classroom version of Witness to Apartheid made possible by the Aaron Diamond Foundation. Introduction The story Witness to Apartheid tells is stark: children in South Africa - the same age as students we teach - are today being beaten, detained, even tortured. As one recent human rights report summarizes, the South African government is waging a 'kar against children.'' The images of Witness to Apartheid are not seen on the evening news: a father shares his feelings about the cold-blooded murder of his son by a South African policeman; a young woman describes the hideous torture she experienced while in police custody; a young man mumbles that he doesn't want to go on living - his beatings by security forces have left him permanently disabled.