Climate Change: Overview and Implications for Wildlife TERRY L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Management in the National Parks

wildlife management IN THE NATIONAL PARKS wildlife management IN IHE NATIONAL PARKS 1969 REPRINT FROM ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES FOR NATURAL AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • NATIONAL PARK SERVICE For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL PARKS ADVISORY BOARD ON WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, APPOINTED BY SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR UDALL A. S. Leopold (Chairman), S. A. Cain, C. M. Cottam, I. N. Gabrielson, T. L. Kimball March 4, 1963 Historical In the Congressional Act of 1916 which created the National Park Service, preservation of native animal' life was clearly specified as one of the pur poses of the parks. A frequently quoted passage of the Act states "... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoy ment of future generations." In implementing this Act, the newly formed Park Service developed a philosophy of wildlife protection, which in that era was indeed the most obvious and immediate need in wildlife conservation. Thus the parks were established as refuges, the animal populations were protected from wildfire. For a time predators were controlled to protect the "good" ani mals from the "bad" ones, but this endeavor mercifully ceased in the 1930's. On the whole, there was little major change in the Park Service practice of wildlife management during the first 40 years of its existence. -

EAZA Bushmeat Campaign

B USHMEAT | R AINFOREST | T IGER | S HELLSHOCK | R HINO | M ADAGASCAR | A MPHIBIAN | C ARNIVORE | A PE EAZA Conservation Campaigns EAZA Bushmeat Over the last ten years Europe’s leading zoos and aquariums have worked together in addressing a variety of issues affecting a range of species and Campaign habitats. EAZA’s annual conservation campaigns have raised funds and promoted awareness amongst 2000-2001 millions of zoo visitors each year, as well as providing the impetus for key regulatory change. | INTRODUCTION | The first of EAZA's annual conservation campaigns addressed the issue of the unsustainable and illegal hunting and trade of threatened wildlife, in particular the great apes. Bushmeat is a term commonly used to describe the hunting and trade of wild meat. For the Bushmeat Campaign EAZA collaborated with the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) as an official partner in order to enhance the chances of a successful campaign. The Bushmeat Campaign can be regarded as the ‘template campaign’ for the EAZA conservation campaigns that followed over the subsequent ten years. | CAMPAIGN AIMS | Through launching the Bushmeat Campaign EAZA hoped to make a meaningful contribution to the conservation of great apes in the wild, particularly in Africa, over the next 20 to 50 years. The bushmeat trade was (and still is) a serious threat to the survival of apes in the wild. Habitat loss and deforestation have historically been the major causal factors for declining populations of great apes, but experts now agree that the illegal commercial bushmeat trade has surpassed habitat loss as the primary threat to ape populations. -

Supplemental Wildlife Food Planting Manual for the Southeast • Contents

Supplemental Wildlife Food Planting Manual for the Southeast • Contents Managing Plant Succession ................................ 4 Openings ............................................................. 6 Food Plot Size and Placement ............................ 6 Soil Quality and Fertilization .............................. 6 Preparing Food Plots .......................................... 7 Supplemental Forages ............................................................................................................................. 8 Planting Mixtures/Strip Plantings ......................................................................................................... 9 Legume Seed Inoculation ...................................................................................................................... 9 White-Tailed Deer ............................................................................................................................... 10 Eastern Wild Turkey ............................................................................................................................ 11 Northern Bobwhite .............................................................................................................................. 12 Mourning Dove ................................................................................................................................... 13 Waterfowl ............................................................................................................................................ -

Effects of Global Warming on Wildlife and Human Health

Effects of Global Warming on Wildlife and Human Health Jennifer Lopez Editor Werner Lang Aurora McClain csd Center for Sustainable Development I-Context Challenge 2 1.2 Effects of Global Warming on Health Effects of Global Warm- ing on Wildlife and Human Health Jennifer Lopez Based on a presentation by Dr. Camille Parmesan main picture of presentation Figure 1: Earth from Outer Space. Introduction of greenhouse emissions.”4 Finally in 2007, the Fourth IPCC Assessment report concluded Global warming is defined as “the increase that the “warming of the climate system is un- in the average measured temperature of the equivocal” and “is very likely [> 90% sure] due Earth’s near surface air and oceans”.1 For the to observed increases in anthropogenic green- past several decades scientists have docu- house gas concentrations.”5 Based on these mented multiple aspects of climate change, conclusions, many scientists and environmen- including rising surface air temperature, rising talists have focused their efforts on sustainable ocean temperature, changes in rain and snow- living and are pushing for energy alternatives fall patterns, declines in permanent snowpack which produce little or no carbon-dioxide to and sea ice, and a rise in sea level.2 Through reduce greenhouse gas emissions. their research, scientists have been able not only to document changes in climate and the Effects of temperature change physical environment, but have also docu- mented effects that this phenomenon is having Scientists have concluded that in the past 100 on the world’s ecosystems and species, many years, the Earth’s average air temperature has of which are negative. -

Nature's Benefits ESA

DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE ECOSYSTEM SERVICES WHITE PAPER NATURE’S BENEFITS: THE IMPORTANCE OF ADDRESSING BIODIVERSITY IN ECOSYSTEM SERVICE PROGRAMS ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION Defenders of Wildlife has been a leader in addressing ecosystem services and market-based programs, one of the first nonprofit organizations to explore policies guiding these programs. This white paper examines the process for addressing ecosystem services in decision-making, in hopes that these concepts encourage policy-makers to balance the interests of nature and society. Author: Sara Vickerman Designer: Kassandra Kelly Defenders of Wildlife is a national, nonprofit membership organization dedicated to the protection of all native wild animals and plants in their natural communities. Jamie Rappaport Clark, President and CEO Donald Barry, Executive Vice President © 2013 Defenders of Wildlife 1130 17th Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036-4604 202.682.9400 www.defenders.org Cover images, clockwise from top: Black-footed ferret, photo by Ryan Hagerty, USFWS; Burrowing owls, photo by Lee Karney, USFWS; Western painted turtle, photo by Gary M. Scholtz, USFWS; Canada geese, Nisqually NWR, photo by Bruce Taylor; Student at Wetzel Woods Conservation Easement during Alterna- tive Outdoor School, photo courtesy of the Friends of Tualatin River NWR and the Conservation Registry. Back cover: Rockefeller Forest, Humboldt Redwoods State Park, photo by Bruce Taylor. INTRODUCTION he concept of ecosystem services – or the benefits that nature provides – has gained tremendous attention over the past decade. It is a common-sense approach to manage- ment that recognizes and makes the most of nature’sT contributions to human communities. Solutions based on ecosystem services generally avoid up-front costs and expensive maintenance of highly engineered alternatives. -

Put the Life Back in Wildlife Grade 8

OSPI-Developed Performance Assessment A Component of the Washington State Assessment System The Arts: Visual Arts Put the Life Back in Wildlife Grade 8 Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction September 2018 Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Old Capitol Building P.O. Box 47200 Olympia, WA 98504-7200 For more information about the contents of this document, please contact: Anne Banks, The Arts Program Supervisor Phone: 360-725-4966 email: [email protected] Or contact the Resource Center at 888-595-3276, TTY 360-664-3631 OSPI provides equal access to all programs and services without discrimination based on sex, race, creed, religion, color, national origin, age, honorably discharged veteran or military status, sexual orientation including gender expression or identity, the presence of any sensory, mental, or physical disability, or the use of a trained dog guide or service animal by a person with a disability. Questions and complaints of alleged discrimination should be directed to the Equity and Civil Rights Director at 360-725-6162 or P.O. Box 47200 Olympia, WA 98504-7200. Except where otherwise noted, this Washington Arts K–12 assessment by the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. All logos and trademarks are property of their respective owners. This work references the Washington State Learning Standards in The Arts (http://www.k12.wa.us/Arts/Standards/default.aspx). All standards designations are from the National Core Arts Standards (http://nationalartsstandards.org/). Copyright © 2015 National Coalition for Core Arts Standards/All Rights Reserved—Rights Administered by SEADAE. -

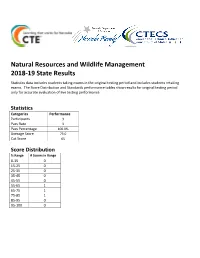

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management Statistics

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 2018-19 State Results Statistics data includes students taking exams in the original testing period and includes students retaking exams. The Score Distribution and Standards performance tables show results for original testing period only for accurate evaluation of live testing performance. Statistics Categories Performance Participants 3 Pass Rate 3 Pass Percentage 100.0% Average Score 73.0 Cut Score 65 Score Distribution % Range # Scores in Range 0-15 0 15-25 0 25-35 0 35-45 0 45-55 0 55-65 1 65-75 1 75-85 1 85-95 0 95-100 0 Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 1) CONTENT STANDARD 1.0: EXPLORE NATURAL RESOURCE SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 75.93% 1) Performance Standard 1.1 : Investigate the Relationship Between Natural Resources and Society, Including Conflict Management 72.22% 1) 1.1.1 Define natural resource management 77.78% 3) 1.1.3 Describe human dependency and demands on natural resources 88.89% 4) 1.1.4 Explain natural resource conservation 66.67% 5) 1.1.5 Investigate the effects of multiple uses of natural resources (e.g., recreation, mining, agriculture, forestry, public lands grazing, etc.) 66.67% 6) 1.1.6 Analyze societal issues related to natural resource management 50% 2) Performance Standard 1.2 : Explain Interrelationships Between Natural Resources and Humans in Managing Natural Environments 86.67% 1) 1.2.1 Explain the effects and/or trade-off of population growth, greater energy consumption, and increased technology and development on natural resources and the environment 83.33% -

The Economics of Threatened Species Conservation: a Review and Analysis

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service 2009 The Economics of Threatened Species Conservation: A Review and Analysis Ray T. Sterner U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, National Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Sterner, Ray T., "The Economics of Threatened Species Conservation: A Review and Analysis" (2009). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 978. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/978 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. In: ÿ and book of Nature Conservation ISBN 978-1 -60692-993-3 Editor: Jason B. Aronoff O 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 8 Ray T. Sterner1 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, National Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, Colorado 80521-2154, USA Stabilizing human population size and reducing human-caused impacts on the environment are lceys to conserving threatened species (TS). Earth's human population is =: 7 billion and increasing by =: 76 million per year. This equates to a human birth-death ratio of 2.35 annually. The 2007 Red List prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) categorized 16,306 species of vertebrates, invertebrates, plants, and other organisms (e.g., lichens, algae) as TS. -

Responsible Human Use of Wildlife

Standing Position Responsible Human Use of Wildlife Because humans are part of a functioning environment, we ultimately and legitimately derive our livelihood, and many of our cultural values, from the resource base. Human societies have recognized and accepted the use of wildlife resources for food, clothing, shelter, hunting, fishing, trapping, viewing, recreation, and as an indicator of environmental quality. All humans and human societies use wildlife directly and/or indirectly, because wildlife generates tangible goods and income and contributes to the economic and spiritual well-being of society. However, human use of natural resources, including wildlife, must be carried out in a responsible manner so that ecological processes can continue to function and sustain a diverse, healthy environment. This, in turn, will result in the continued well-being of both humans and wildlife. Human activities are a major factor in ecosystem disruption worldwide. Human population growth and technological development result in dramatic reductions and alterations in quality and availability of wildlife habitat, over-use of some wildlife species, greater human dependence on domesticated animals, and changes in the functioning of most ecosystems. Abuse of the land and water resources exacerbates the decline of natural resources and deterioration of the ecosystem’s abilities to support wildlife and human populations. Maintenance, restoration, and enhancement of wildlife populations and habitat characteristics through scientific management and regulations are vital to ecological functioning, genetic diversity, and perpetuation of wildlife populations, species, and habitats. Conservation-minded citizens and resource management professionals can successfully slow or reverse the decline of wildlife species and destruction of habitats. Prudent management practices and regulations, supported by a conservation-minded public, are essential for restoration of wildlife species, populations, and habitat productivity. -

For-74: a Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning

FOR-74 A Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning Thomas G. Barnes, Extension Wildlife Specialist Lowell Adams, National Institute for Urban Wildlife entuckians value their forests and Kother natural resources for aes- Guidelines for Considering Wildlife in the Urban Development thetic, recreational, and economic Process significance, so over the past several Promote habitats that will have the food, cover, water, and living space that decades they have become increasingly all wildlife require by following these guidelines: concerned about the loss of wildlife • Before development, maximize open space and make an effort to protect the habitat and greenspace. Urban and most valuable wildlife habitat by placing buildings on less important portions suburban development is one of the of the site. Choosing cluster development, which is flexible, can help. leading causes of this loss: A recent • Provide water, and design stormwater control impoundments to benefit wildlife. study indicated that every day in • Use native plants that have value for wildlife as well as aesthetic appeal. Kentucky more than 100 acres of rural • Provide bird-feeding stations and nest boxes for cavity-nesting birds like land is being converted to urban house wrens and wood ducks. development. • Educate residents about wildlife conservation, using, for example, informa- Because concern for loss of tion packets or a nature trail through open space. greenspace is not new, we have for • Ensure a commitment to managing urban wildlife habitats. some time created attractive urban greenspace environments with our parks and backyards. These The publication can also be useful to A landscape is a large area com- greenspaces have been created not so the average homeowner in understand- posed of ecosystems (the plants, much for wildlife habitats as for people ing the complex issues involved in animals, other living organisms, and to enjoy, but the potential for wildlife landscape planning and wildlife their physical surroundings). -

Illegal and Unsustainable Hunting of Wildlife for Bushmeat in Sub-Saharan Africa

About the Wilderness Problem-Specific Guide Series These guides summarize knowledge about how wildlife authorities can reduce the harm caused by specific wildlife crime problems. They are guides to preventing and improving the overall response to incidents, not to investigating offenses or handling specific incidents; neither do they cover technical details about how to implement specific responses. Who is this bushmeat guide for? This guide is aimed at wildlife officers and non-governmental conservation practitioners who have identified the illegal and unsustainable hunting of wildlife for bushmeat, as an important threat in a specific site or landscape. These include: ñ Protected Area Managers and their deputies ñ Conservation NGO Project Leads ñ Wildlife officers and NGO conservation practitioners of whatever rank or assignment, who have been tasked to address the problem These guides will be most useful to problem solvers who: Understand basic problem-oriented policing principles and methods. The guides are designed to help conservation practitioners decide how best to analyze Scanning Analysis Collect and analyze and address a problem they have already Identify and prioritize information to determine problems. Choose one what drives and facilitates identified. The guides are structured in specific problem. the same way as the SARA process the problem. (right). This covers how to define your problem (Scan); questions you will need to answer to guide you to an effective intervention (Analysis); types of interventions you could use (Response); and ways to check if your intervention worked (Assessment). Response Assessment Implement response that reduces drivers and For a primer on Problem-Oriented Determine the impact of your facilitators of the problem. -

Effects of Oil on Wildlife and Habitat the U.S

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Effects of Oil on Wildlife and Habitat The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Weathering reduces the more toxic elements in oil products over time as Service is the federal exposure to air, sunlight, wave and tidal action, and certain microscopic agency responsible for organisms degrade and disperse many of the nation’s fish oil. Weathering rates depend on factors such as type of oil, weather, and wildlife resources and temperature, and the type of shoreline one of the primary trustees and bottom that occur in the spill area. for fish, wildlife and habitat Types of Oil Although there are different types of at oil spills. oil, the oil involved in the Deepwater Horizon spill is classified as light crude. The Service is actively involved Light crude is moderately volatile and in response efforts related to the can leave a residue of up to one third of Deepwater Horizon oil spill that the amount spilled after several days. It occurred in the Gulf of Mexico on April leaves a film on intertidal resources and 20, 2010. Many species of wildlife, has the potential to cause long-term including some that are threatened or contamination. endangered, live along the Gulf Coast and could be impacted by the spill. Impacts to Wildlife and Habitat Oil causes harm to wildlife through Oil spills affect wildlife and their physical contact, ingestion, inhalation habitats in many ways. The severity and absorption. Floating oil can of the injury depends on the type and contaminate plankton, which includes quantity of oil spilled, the season and algae, fish eggs, and the larvae of MacKenzie FWS/Tom weather, the type of shoreline, and the various invertebrates.