Academic Loitering: Observations from Sitting in Three Toronto Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vertical Files

Bloor/Gladstone Branch Local History Collection Vertical File Subject Headings Architecture Biography - General Biography - Denison Family Biography - Givins Family Biography - Neilson Family Biography - Shaw Family Brandon-Primrose Area Brockton Churches - Alphabetical Churches - General Churches - St. Anne's City Planning - Bloor/Dufferin City Planning - Brock Planning District City Planning - Dovercourt Park Area City Planning - Dufferin Grove Area City Planning - Dundas/Dufferin City Planning - Lionstar (1970 proposed development) City Planning - Wallace Emerson Crime Dovercourt Village Dufferin Mall Dufferin Race Track Elections - General Family Life Festivals Galleries & Museums Garrison Creek Geological Features Gore Vale Hotels & Taverns Houses - by Street Name Housing Industry - Pollution Industry & Commerce Libraries - Bloor/Gladstone Library Libraries - College/Shaw, Runnymede, Dufferin/St. Clair Maps - 1979 -- Maps - Electoral Divisions Oral History - No File (Bloor/Dufferin interviews transferred to TPL Archives) Parkdale Parks Parks - Dufferin Grove Park Police Politics & Government Population Population - Black Community Population - Italian Community Population - Jewish Community Population - Multiculturalism Population - Portuguese Community Postal Service Protestant Orphans' Home Schools - General Information Schools - Bishop Marrocco Schools - Bloor Collegiate Schools - Brock Ave School Schools - Brockton High School Schools - Central Commerce High School Schools - Christie Public School Schools - Dewson Public School -

Welcome to the City of Toronto Staff Team

Parks, Forestry & Recreation WADING POOL MANUAL Welcome to the City of Toronto Staff Team ............................................................................................................ 5 PARKS, FORESTRY & RECREATION VISION AND MISSION ....................................................................... 5 Contact Numbers and Pool Locations ...................................................................................................................... 6 Etobicoke York District Locations and Contacts ..................................................................................................... 8 North York District Locations and Contacts ............................................................................................................ 9 Scarborough District Locations and Contacts .......................................................................................................... 9 Toronto & East York District Wading Pool Locations .......................................................................................... 10 Section 1 Customer Service ........................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 The Golden Rules of Customer Service ......................................................................................... 13 1.2 Responding to Customer Complaints ............................................................................................. 14 Section 2 Responsibilities ............................................................................................................................. -

Name of Group

Name of Group 18 Yorkville Condominium ABC Residents Association Alex Wilson Community Garden Alliance of Seniors Annex Residents Association Antibes Steering Committee Aquatic Working Group Argonaut Rowing Club Baird Park Improvement Committee Bathurst Jewish Community Centre Bay Cloverhill Community Association Beaches R.C. Advisory Council Beautification of Barbara Ann Scott (Canderel/GWL/ Liberties) Bellevue Square Ben Nobleman Orchard Bendale Acres Birkdale Seniors Executive Bleecker St Coop Bloor - Yorkville BIA Bloor Annex BIA Bloor by the Park BIA Bloordale Advisory Board Bob Abate C.C. Advisory Council Breakfast Club Advisory Council Call-A-Service Inc./Harmony Hall Centre For Seniors Campbell House Museum Cawthra Dog-off Leash Cedarvale Community Gardens / Children's Garden Cedarvale Dog Owner Association Cedarvale Oldtimers Hockey Centennial College Recreation Leadership Program Centennial Park Skating Club Children's Garden Program Chinese Chamber of Commerce Christie Ossington Residents Association Church - Wellesley BIA Church of the Holy Trinity Churchill Dog Owner Association Community Gardeners Copernicus Lodge Coxwell Parkette (Danforth Mosiac BIA) Curran Hall Community Association Dog Owners' Association Don Montgomery Seniors Executive Downsview Services to Seniors Inc. Downtown Yonge BIA Driftwood Advisory Council Driftwood Community Centre Dufferin/Davenport Community Centre (Older Adults) Dundas St. Clarens Parkette E.P. Taylor Place (Don Mills Foundation for Senior Citizens Inc). E.Y. Canada Day Committee E.Y. Garden Club Earl Beatty Advisory Council Earl Beatty C.C. East Lynn Community East York Garden Club Ecology Park Community Garden Eglinton Hill BIA Elder Connections Elmbank Advisory Council Etobicoke Services For Seniors Evergreen Foundation Fairfield Advisory Council Fairmount Park C.C. Flemington Park Parents Association Forest Hill BIA Frankel Lambert Community Garden Frankland C.C. -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

556 Concord Avenue Location! Location!

556 Concord Avenue Location! Location! Check out the YouTube video at www.LovelyTorontoHomes.com Julie Kinnear*, Jennifer Palacios*, Holly Chandler* & Tyler Delaney* *Sales Representative Julie Kinnear*, Jennifer Palacios,* Office 416.236.1392 Direct 416.762.5949 Holly Chandler* & Tyler Delaney* *Sales Representative [email protected] s www.juliekinnear.com Office 416.236.1392 Direct 416.762.5949 Prospective purchasers should satisfy themselves as to the accuracy of the information contained in this feature sheet. All measurements are approximate. The statement contained herein are based upon information furnished by principals and sources which we believe are reliable, but for which we assume no responsibility. Not intended to solicit parties under any agency contract. [email protected] s www.juliekinnear.com Upgrades & Improvements 556 Concord Avenue, Toronto ● Sturdy & dry detached 1 car garage has lots of extra space Check out the YouTube video at for storing bikes and gardening equipment. Accessed off the 2014 ~ Central air conditioning back laneway for ease of bringing your groceries right into the 2011 ~ Flat roof & eavestroughing system www.LovelyTorontoHomes.com kitchen. 2010 ~ Front & rear doors main floor, Landscaping 2009 ~ Rear waterproofing, Stone patio and wooden back deck, Siding & duro foam insulation ● Got a green thumb? Enjoy the extensive mature rear gardens 2007 ~ Replaced all basement windows Nearby Downtown, Family Friendly ‘Hood’ with flagstone pathway! Fully fenced very private yard perfect for 2006 ~ Excavation and replacement of 10 feet of clay pipe in lower level with new 4”, PVC piping and replaced the floor drain. Retiled the ● Spacious, bright & beautifully upgraded semi is move-in pets play and entertaining! mud room in the lower level, Retiled basement bath with porcelain ready! 2003 ~ Furnace & Water heater, Re-shingled the roof & garage ● Hip & happening “hood”! – Get in while you still can! Walk to the 2002 ~ Opened up the main floor - removed wall, added new oak hardwood flooring and new ceiling. -

Staff Report

STAFF REPORT August 20, 2004 To: Community Services Committee From: Commissioner of Community and Neighbourhood Services Subject: Final Update on 2002/03 Ontario Works (OW) Incentive Fund Purpose: The purpose of this report is to update City Council on the implementation and results of the 55 projects funded by the one-time provincial incentive funds received by Toronto Social Services (TSS) in 2001 for exceeding Ontario Works (OW) placement targets. Financial Implications and Impact Statement: There are no net impacts on the 2004 budget. All Ontario Works Incentive projects are funded from one-time 100 percent provincial funds. Recommendations: It is recommended that this report be received for information. Background: At its meeting of May 21, 22 and 23, 2002, Council approved a report, titled “Allocation of Ontario Works Targets Incentive Funds,” which recommended the expenditure of $5.1 million to fund 55 projects. Ontario Works Incentive Funds were offered by the Province to increase the number of clients participating in the Community Participation component of Ontario Works. Ministry of Community and Social Services guidelines stipulate that the funds must be used to meet local human service needs and that they cannot accrue as savings, be used to address municipal budget pressures, or offset costs related to regular program expenses. The 55 funded projects addressed the needs of at-risk youth populations, and related food and hunger and safety issues in disadvantaged communities. - 2 - At its meeting of January 27, 28 and 29, 2004, Council adopted a report, titled “2002/03 Ontario Works (OW) Incentive Fund,” which recommended that up to nine of the 55 projects funded be extended to June 2004. -

Landscape Architect Quarterly Features CSLA Awards OALA Awards Round Table Winning Trends Summer 2009 Issue 06

06 Landscape Architect Quarterly 10/ Features CSLA Awards OALA Awards 16/ Round Table Winning Trends Summer 2009 Issue 06 P u b l i c a t i o n # 4 0 0 2 6 1 0 6 Messages .06 03 Letters to the Editor President’s Message I particularly enjoyed the issue on trees [ Ground 05]. Like the previous I am honoured to hold the prestigious office of OALA President issues, Ground includes articles that are theoretical and challenging and look forward to serving the membership. The president’s job while providing practical information that is relevant to our practice is typically a busy one; however, I am comforted by the knowledge in Ontario. that I am surrounded by extremely talented and dedicated coun - cillors who are there to help. On behalf of Council, I extend a One concern I have is that the images don't seem to be as crisp as heartfelt thanks to Arnis Budrevics for his successful tenure as they could or should be. Since our profession is quite visually orient - president for the past two years. ed, can the images in Ground be printed with greater clarity without compromising any sustainability objectives you might have? The OALA held its 41st Annual General Meeting on May 6, 2009 at the Grand Hotel in Toronto. This was another successful event Finally, congratulations on the CSLA award that Ground received and included presentations of the OALA Awards and the CSLA this year. The award is well-deserved acknowledgement of your Regional Awards of Excellence that are featured in this issue of great work and recognizes the passion and commitment of the Ground . -

Date and Contract # Consultant's Name

Date and contract # Consultant’s name Description of work Contract value (actual?) expenditure 1998 no numbers No names Retraining of City workers $500,000 from the Source: Corporate Workforce Reduction and Services Committee Retraining Reserve fund minutes, March 25, 1999 1999 no numbers No names Retraining of City workers $2,000,000 Source: Corporate Services Committee minutes, March 25, 1999 1999 no day/month, no p.o. David A.Clark Consulting Inc. Travel/accomodation/ ? $1783.45 number consulting fees 1999 no day/month, no p.o. Randolph Group Management No description ? $6,799.37 number Consulting Inc. 1999 no day/month, no p.o. Randolph Group Report:“Recreation Program ? $60,990 number Harmonization project” C.A.P. 04-1318 1999 no day/month, no p.o. TS Health and Safety No description ? $499.55 number Consultants Inc. 7/9/99 no p.o. number FHG International Inc. The Food Services Report ? $75,023.05 C.A.P. 04-1318 25/10/99 #3004374 Graeme Page Associates Theatre study for the City $39,140 Amount paid net: $39,140 our reference “no of Toronto reference” C.A.P. 04-1580 29/11/99 #6000005 Coll. Architects To provide consulting $4,707.08 Amount paid net; $4,711.72 our reference “No services for the renovation Reference” of three (3) washroom/field C.A.P. 04-1580 house buildings (Stanley Park North Washroom, Bellevue Square park and Trinity Bellwoods field house 29/11/99 #6000007 Thomas Brown Architects To provide consulting $9,135.23 Amount paid net: $6065.20 our reference “No Inc. -

Ward 18 - Davenport P S

City of Toronto Ward Profiles Ward Key Ward 18 - Davenport S D B S B P o e a a r m r l i l r i a s e m s Ave t e ando e Av h l m C w Pelha t m e o r r s Ave a Caru t s o K n l i gs y Ave t le r A e A s e A t O e v v v H A e A o e s A o e k v l v N A v e e e v N e r e N S Wychcrest Ave t Acores Ave Geary Ave Melita Cres Hugo Ave C P R E F M d r M a w e A a n Dupont St K d i z v t n Annette S k l i e a l e e A i n t n l y e v d S A e C S l L t v S e E a t a Burnfield Ave e Melville t Ave n m m S s e p B d t r b o S a s e w r umberside Ave o h H C s l t Yarmouth Rd l n a l n e e ler St Lappin Av e t r An A N w e A t C v t I A v n e S A d R Hallam St n e v d t v a e W e I v v l A e Garnet A i n e d a h D a Millicent St G e d n t n Ke ne P e kin Ave r M i Rus l a e d a l R a n r S d D S o t w P h St y Jerome s G a ssex St t E a a m t u A d ve o r Armstrong A r c v e v i n f i C n C f e f e i g A o c r e e t A n Abbott Ave v A o r s e c v Pendrith St n v Ave i Southview o Wallace Ave e n e A r d v S Glenlake Ave e A v t t e D Shanly S o R P r a M u v O u Wanda Rd s a o S s l l a ve i A u Ernest R a n e ds St k d Lee R Paton R n a l e t C m e t t d n v m a A A k o i i r v e n v u l A i e w e n n C Jenet Ave v t g r A e e R St d A s Northumberlan v d e v Edna Ave e Bloor St A M C l h o r a n a m t w r S Indian Trl o b f s o t r a e r H Croatia St d A A e S v l v e t e Radford Ave St e n Hepbourne D ' S o R M Ridout St S A v u t e a R v s ad Ave C H r te r Bous e o h c g e l a x o a o v e u v t l u v r A e o m e A e S e r r i n l t n e n e h o -

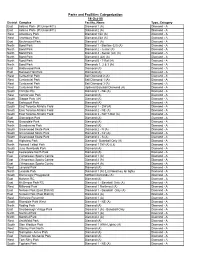

Parks and Facilities Categorization 14-Oct-05

Parks and Facilities Categorization 14-Oct-05 District Complex Facility_Name Type_Category East Adams Park- (Pt Union/401) Diamond 1 (A) Diamond - A East Adams Park- (Pt Union/401) Diamond 2 (A) Diamond - A West Amesbury Park Diamond 1/Lit (A) Diamond - A West Amesbury Park Diamond 2/Lit (A) Diamond - A East Birchmount Park Diamond 1 (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 1 - Bantam (Lit) (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 2 - Junior (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 3 - Senior (Lit) (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 4 (Lit) (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamond 5 - T-Ball (A) Diamond - A North Bond Park Diamonds 1, 2 & 3 (A) Diamond - A East Bridlewood Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A East Burrows Hall Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A West Centennial Park Ball Diamond 2 (A) Diamond - A West Centennial Park Ball Diamond 1 (A) Diamond - A West Centennial Park Ball Diamond 3 (A) Diamond - A West Centennial Park Optimist Baseball Diamond (A) Diamond - A South Christie Pits Diamond 1 - NE (A) Diamond - A West Connorvale Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A South Dieppe Park AIR Diamond (A) Diamond - A West Earlscourt Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A South East Toronto Athletic Field Diamond 1 - SW (A) Diamond - A South East Toronto Athletic Field Diamond 2 - NE (A) Diamond - A South East Toronto Athletic Field Diamond 3 - NW T-Ball (A) Diamond - A East Glamorgan Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A West Gracedale Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A North Grandravine Park Diamond (A) Diamond - A South Greenwood Skate Park Diamond 2 - N (A) Diamond - A South -

Community Services & Facilities Study

01 INTRODUCTION Dufferin Grove Village 900 Dufferin Street Community Services & Facilities Study July 2019 Urban Strategies Inc. This community services & facilities study was prepared by Urban Strategies Inc. on behalf of Primaris Management Inc., in support of an application to amend the City of Toronto Official Plan and Zoning By-Laws 438-86 and 569-2013 to permit the intensification of the site as a mixed- use commercial and residential development. 2 Dufferin Mall | Community Services & Facilities Study 01 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Executive Summary Section 1 - Introduction 1 Section 2 - About the Development 3 Section 3 - Demographic Profile 5 Section 4 - Development Activity 15 Section 5 - Inventory of Services & Facilities 19 Section 6 - Conclusions 37 Appendix 39 Executive Summary Accessible, high-quality community services Demographic Profile and facilities are critical to promote community The demographic profile of the study area was prepared interaction and engagement in community life, based on data from the 2016 census by Statistics Canada, and to provide opportunities for education and based on a boundary provided by City of Toronto Planning recreation. To that end, this Community Services staff. Where relevant, demographic data for the study area is & Facilities Study identifies the current and compared against data for the city as a whole. required levels of social infrastructure required The following are key findings from the analysis: to support the health, safety and well-being of • The population of the study -

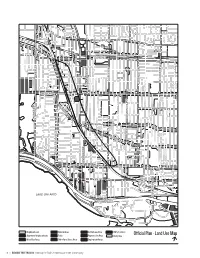

Land Use Map Mixed Use Areas Other Open Space Areas Employment Areas

ST CLAIR AVE WEST DAVENPORT DUPONT KEELE CHRISTIE DUFFERIN OSSINGTON LANSDOWNE BLOOR DUNDAS HARBORD PARKSIDE DOVERCOURT COLLEGE DUNDAS RONCESVALLES LANSDOWNE QUEEN KING LAKE ONTARIO STRACHAN GARDINER EX LA K E S H ORE Neighbourhoods Natural Areas Institutional Areas Utility Corridors Apartment Neighbourhoods Parks Regeneration Areas Study Area Official Plan - Land Use Map Mixed Use Areas Other Open Space Areas Employment Areas 18 | BESIDE THE TRACKS: Knitting the Rail Corridor back to the Community DUPONT DUPONT LANSDOWNE DUFFERIN BLOOR BLOOR DUNDAS DOVERCOURT COLLEGE DUNDAS RONCESVALLES LANSDOWNE QUEEN QUEEN Study Area Employment Industrial Refer to former municipal Residential Open Space zoning by-law Zoning By-law 569-2013 Commercial Residential Utility and Transportation BESIDE THE TRACKS: Knitting the Rail Corridor back to the Community | 19 2.3 EXISTING BUILT FORM & CHARACTER The Study Area is compromised of a mix of land uses with areas furthest from the rail lines and between the avenues as primarily low-rise residential dwellings. Within these neighbourhoods, a distinct porch character has been noted as important by the communities. Areas along the Avenues, i.e., Bloor Street, Dundas Street and Queen Street are primarily mixed use in nature with commercial storefronts and residential units above. High-rise residential buildings approximately 9 to 15 storeys in height, also exist along Bloor Street West; however the majority buildings are low to mid-rise Porch character is a notable design feature within the neighbourhood in character. There are also a number of large former industrial sites that are located along the railway lines in the west. An important characteristic of the communities in the Study Area is the physical isolation from the west, and sections of the east and north, primarily due to the railway corridors.