Salvation in Christ.Qxp 4/29/2005 4:08 PM Page 53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soteriology 1 Soteriology

Soteriology 1 Soteriology OVERVIEW 2 Sin and Salvation 2 The Gospel 3 Three broad aspects 4 Justification 4 Sanctification 5 Glorification 6 ATONEMENT 6 General Results 6 Old Testament Background 6 Sacrifice of Jesus 7 Atonement Theories 9 Extent of the Atonement 10 Synthesis 11 FAITH AND GRACE 13 Types of Faith 13 Christian concept of Faith 14 Rev. J. Wesley Evans Soteriology 2 Grace 15 Nature of Grace 15 Types of Grace 15 Sufficient and Efficacious 15 General effects of Grace (acc. to Aquinas II.I.111.3) 16 THE SALVATION PROCESS 16 Overview Sin and Salvation General Principal: The nature of the problem determines the nature of the solution Problem (Sin related issues) Solution (Salvation) Broken relationship with God Reconciliation and Adoption Death of the Soul (Original Sin) Soul regenerated, allowing the will to seek God Humans under God’s judgment Promise of forgiveness and mercy Corruption of the world, broken Future New Creation relationship with the natural world Evil and unjust human systems Future inauguration of the Kingdom of God Temptation of Satan and fallen angels Future judgment on evil The list above of the sacraments is my own speculation, it seems to “fit” at this point. Rev. J. Wesley Evans Soteriology 3 The Gospel Mark 1:1 The beginning of the good news [ euvaggeli,ou ] of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. Luke 9:6 They departed and went through the villages, bringing the good news [euvaggelizo,menoi ] and curing diseases everywhere. Acts 5:42 And every day in the temple and at home they did not cease to teach and proclaim [ euvaggelizo,menoi ] Jesus as the Messiah. -

Comparative Soteriology and Logical Incompatibility

COMPARATIVE SOTERIOLOGY AND LOGICAL INCOMPATIBILITY by Shandon L. Guthrie INTRODUCTION There is a tremendous amount of material that could have been included in this work on comparative soteriology; Nonetheless, I will attempt to encompass a variety of religious belief systems. I have selected Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity as world-wide representatives of different schools of thought. (1) When we think of religion, (2) we normally conjure up images of rules and regulations. In fact, most religions are primarily centered on some principle or guideline to follow in order to sustain or create some type of welfare for the individual. For this reason religion ultimately represents the desired path of each person who holds to some type of religious system. This brings us to the concept of soteriology . The term soteriology refers to the method or system of how one ought to operate in order to maximize personal and/or corporate salvation. Salvation itself actually carries a variety of definitions; However, the most basic way of defining it is in terms of "deliverance" or "welfare." (3) The question that immediately comes to mind is, "What exactly is one being 'delivered' or 'saved' from?" Indeed, every religion carries its own system and interpretation on such matters as these. Therefore, we shall examine and analyze each soteriological system according to the respective religion and determine if any or all religions can be simultaneously true. JUDAISM Judaism, like many religions, is a religion stemming from a long history of war and slavery. The most known aspects of Judaism are the dietary regulations, cultural practices, and political practices. -

The Death and Resurrection of Christ in the Soteriology

THE DEATH AND RESURRECTION OF CHRIST IN THE SOTERIOLOGY OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM by George H. Wright, Jr., A.B. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University in Partial Fulfillment of the Re quirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin July, 1966 PREFACE It i. quite evident that there ha. been a movement durinl the pa.t thirty years or .0 away hOll an empba.ia on the death of Chriat to a focus on the Re.urreetion, or at l.alt to an interpre- tatioo which .how. tb4t death and reaurnction are intell'&l1y one. Thia reDewed intereat in the ailDiflcan,ee of Chrht·. re.urrection ha. been the ocea.ion fora re-exaeinatlon of many, if not all, area. of theology, includinl the QY area of .otedology. Recent UM' have abo witn.... d a renewed inter•• t in Pattiatic studie.. Th. school of Antioch, In particular,. ha. belUD to be ••en in a more favorable 11Cht. Wlth rare exe.ptionl, the theololian. of thia .ehool hav., until r.cently, b.en totally for- lot ten or 41 __ i •••d a. heretie.. Th. critlci.. that was leveled malnly .t the extreme po.ition. tekeD by individual. luch a. Ne.toriu. haft overahadowed the coapletely ol'th04ox beUd. of many Antiochene theololian•• CBJ:e of the 1'8"00. for _kiDI thh .tudy .... to dileover what place the AntiocheD" live to Chri.t'. death and re.urrection in their teachine about the Redemption. Thh va. done not only out of an intere.t in the current .pha.h OIl the Re.urrection and in the Antiochene School, but ... -

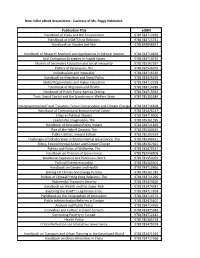

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Soteriology - the Doctrine of Salvation

Tuesday, 29 September 2020 Soteriology - The doctrine of Salvation Subject • Love God more deeply for what He did for you. • Tell others more confidently what God can do for them. • Have an assurance of your salvation and an appreciation for God’s grace. • The problem: the need for salvation • The provision: the solution of salvation • The promise: the security of salvation Soteriology discusses how Christ’s death secures the salvation of those who believe. It helps us to understand the doctrines of redemption, justification, sanctification, propitiation, and the substitutionary atonement. Some common questions in studying Soteriology are: Understanding Biblical Soteriology will help us to know why salvation is by grace alone (Ephesians 2:8-9), through faith alone, in Jesus Christ alone. No other religion bases salvation on faith alone. Soteriology helps us to see why. A clear understanding of our salvation will provide a "peace that passes all understanding" (Philippians 4:7) because we come to know that He who can never fail is the means by which we were saved and the means by which we remain secure in our salvation. If we were responsible to save ourselves and keep ourselves saved, we would fail. Thank God that is not the case! KEY VERSE: Titus 3:5-8 is a tremendous summary of Soteriology, "He saved us, not because of righteous things we had done, but because of His mercy. He saved us through the washing of rebirth and renewal by the Holy Spirit, whom He poured out on us generously through Jesus Christ our Saviour, so that, having been justified by His grace, we might become heirs having the hope of eternal life.” RT KENDALL The most important subject of all It deals with the REASON God sent his son into the world It deals with our own souls and where we will spend eternity It equips us in how and what we share in evangelism. -

Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20Th and 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto ASPECTS OF ARMINIAN SOTERIOLOGY IN METHODIST-LUTHERAN ECUMENICAL DIALOGUES IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY Mikko Satama Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology Department of Systematic Theology Ecumenical Studies 18th January 2009 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO − HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto − Fakultet/Sektion Laitos − Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Systemaattisen teologian laitos Tekijä − Författare Mikko Satama Työn nimi − Arbetets title Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20th and 21st Century Oppiaine − Läroämne Ekumeniikka Työn laji − Arbetets art Aika − Datum Sivumäärä − Sidoantal Pro Gradu -tutkielma 18.1.2009 94 Tiivistelmä − Referat The aim of this thesis is to analyse the key ecumenical dialogues between Methodists and Lutherans from the perspective of Arminian soteriology and Methodist theology in general. The primary research question is defined as: “To what extent do the dialogues under analysis relate to Arminian soteriology?” By seeking an answer to this question, new knowledge is sought on the current soteriological position of the Methodist-Lutheran dialogues, the contemporary Methodist theology and the commonalities between the Lutheran and Arminian understanding of soteriology. This way the soteriological picture of the Methodist-Lutheran discussions is clarified. The dialogues under analysis were selected on the basis of versatility. Firstly, the sole world organisation level dialogue was chosen: The Church – Community of Grace. Additionally, the document World Methodist Council and the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification is analysed as a supporting document. Secondly, a document concerning the discussions between two main-line churches in the United States of America was selected: Confessing Our Faith Together. -

Christian Soteriology

Christian Soteriology Professor: Tarmo Toom, Ph.D., [email protected] Purpose of the Course: The purpose of this course is to study the biblical foundations of soteriology, the historical unfolding of the implications of biblical soteriology, and the contemporary developments in soteriology. A student should become aware of his/her theological presuppositions, acquire an adequate knowledge of the issues involved in soteriology, and demonstrate a competence in explicating seemingly simple questions, “What is salvation?” and “How does salvation work?” Required Textbooks: Dunn, J. D. G. The Theology of Paul the Apostle. Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans, 1998. Green, J. B. and Baker, M. D. Recovering the Scandal of Cross: Atonement in New Testament & Contemporary Contexts. Intervarsity Press, 2000. Joint Declaration of the Doctrine of Justification. Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans, 2000. Weaver, J. D. The Nonviolent Atonement. Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans, 2001. Required Readings (Books and Articles on Reserve): Anselm Why God Became Man? In St. Anselm: Basic Writings. Chicago: Open Court, 1996, 253-302. Aquinas Summa theologica 12ae Q 109, Art. 1-10 in Aquinas on Nature and Grace., ed. A. M. Fairweather. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1954, 137-156. The Arminian Articles in P. Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1998 (reprint), 545-549. Athanasius On the Incarnation. Crestwood: St. Vladimir Seminary Press, 1993, 25-64. Augustine On Nature and Grace, in FC 86, trans. John A. Mourant and William J. Collinge, 1992, 22-90. Boff, L. & C. Salvation and Liberation: In Search of a Balance between Faith and Politics. Trans. R. R. Barr. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1984, 1-66. -

Process Theodicy and the Life After Death: a Possibility Or a Necessity?

PROCESS THEODICY AND THE LIFE AFTER DEATH: A POSSIBILITY OR A NECESSITY? Sofia Vescovelli Abstract: In this paper I argue for the necessity of eschatology for process thought, and against the idea that the belief in a life after death is not an essential element for this theodicy. Without reference to an eschatological dimension, a process theodicy is led to admit a consequentialist conception of divine love and goodness that is inconsistent with its notion of a responsive and participative God who loves each creature. In the world many creatures suffer atrocious evils, which destroy the value of their lives, but the process God does not redeem these sufferings in a personal post-mortem life in which the sufferers participate and can find meaning for their individual evils. In order to support my thesis, I intend to examine some difficulties in process theodicy, especially in Charles Hartshorne’s position, showing how his doctrine of objective immortality is unsatisfactory. My starting point will be some criticisms advanced by John Hick against Hartshorne and the replies made by the process philosopher David R. Griffin. I conclude by contending that process theodicy, at least in its Hartshornean version, in denying the necessity of a personal afterlife, does not provide a satisfying answer to the soteriological-individual aspect of the problem of evil, namely the problem of the individual salvation in which the individual person can find redemption and meaning for the sufferings undergone or inflicted. In the process perspective the divine love is conceived in consequentialist terms and evils suffered by the individual are merely considered a by-product or the negative side of the divine creation out of chaos. -

Religion (Classes BL Through BX)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COLLECTIONS POLICY STATEMENTS Religion (Classes BL through BX) Contents I. Scope II. Research Strengths III. Collecting Policy IV. Acquisition Sources: Current and Future V. Best editions and preferred formats VI. Collecting Levels I. Scope Materials covered by this statement comprise the collections in class BL-BX. As the de facto national library of the United States, the Library of Congress acquires for its permanent collections works of research value in the philosophy of religion; the history and principles of religion; comparative religion; systems of theology and doctrine; law, liturgy, and rituals; religion and society: its historical, social, and cultural role; and trends and developments of current or historic importance. Emphasis is placed on publications of scholarly and research interest at national or international levels. This document excludes religious law (KB-KBX), which is covered by the Law Collections Policy Statement. II. Research Strengths The Library of Congress’s holdings in the area of religion reflect the tremendous depth and breadth of the Library’s collections at large. These materials cover nearly all of the world’s religious traditions, in all manner of formats, dating from before the Common Era down to the present day. The Library has extensive holdings of the foundational texts and other basic writings of all major and many minor religions worldwide. These include all significant editions and translations of the Bible, Talmud, Qur’an, Tripitaka, Vedas, and others, as well as large numbers of interpretive or reference works about them. In addition to the General Collections, the African and Middle Eastern Division, the Asian Division, and the Rare Book and Special Collections Division house significant collections of manuscript and print editions of these sacred texts in their original vernacular languages. -

200 Religion

200 200 Religion Beliefs, attitudes, practices of individuals and groups with respect to the ultimate nature of existences and relationships within the context of revelation, deity, worship Including public relations for religion Class here comparative religion; religions other than Christianity; works dealing with various religions, with religious topics not applied to specific religions; syncretistic religious writings of individuals expressing personal views and not claiming to establish a new religion or to represent an old one Class a specific topic in comparative religion, religions other than Christianity in 201–209. Class public relations for a specific religion or aspect of a religion with the religion or aspect, e.g., public relations for a local Christian church 254 For government policy on religion, see 322 See also 306.6 for sociology of religion See Manual at 130 vs. 200; also at 200 vs. 100; also at 201–209 and 292–299 SUMMARY 200.1–.9 Standard subdivisions 201–209 Specific aspects of religion 210 Philosophy and theory of religion 220 Bible 230 Christianity 240 Christian moral and devotional theology 250 Local Christian church and Christian religious orders 260 Christian social and ecclesiastical theology 270 History, geographic treatment, biography of Christianity 280 Denominations and sects of Christian church 290 Other religions > 200.1–200.9 Standard subdivisions Limited to comparative religion, religion in general .1 Systems, scientific principles, psychology of religion Do not use for classification; class in 201. -

A Historical Overview of Eastern Orthodox Theology on the Doctrine of the Three Offices of Christ

A Historical Overview of Eastern Orthodox Theology on the Doctrine of the Three Offices of Christ by Anatoliy Bandura A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Regis College and the Theology Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology awarded by Regis College and the University of Toronto © Copyright by Anatoliy Bandura 2012 A Historical Overview of Eastern Orthodox Theology on the Doctrine of the Three Offices of Christ Anatoliy Bandura Master of Theology (ThM) Theology Department Regis College of the University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This thesis deals with the dogma of the threefold office of Christ that constitutes an integral component of the Christian doctrine of justification and reconciliation in the West. Though it has a certain value, the tripartite scheme of Christ’s office that presents Him as High Priest, Prophet and King does not exhaust the description of Jesus’ ministry and identity. This thesis looks at the three offices of Christ from an Orthodox perspective, and includes a history and critique of modern Orthodox authors concerning the threefold office. The need for the given thesis is based on the absence of research done by Orthodox thinkers on the doctrine of the Three Offices of Christ and its place in Orthodox theology. Only a few Orthodox dogmatists have written on the said doctrine. They can be separated into two groups: the one attempting to make a unique interpretation of the concept of the threefold ministry of Christ in line with Eastern patristic theology, while the other has been influenced by Western theological approaches to the doctrine. -

The Soteriology of Julian of Norwich and Vatican Ii: A

THE SOTERIOLOGY OF JULIAN OF NORWICH AND VATICAN II: A COMPARATIVE STUDY by Josephine Maria Pace A Thesis subnitted to the Faculty of Theology of the University of St. Michael's College and the Department of Theoloqy of the Toronto SchooL of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theolow awarded by the University of St. Michael's College TORONTO 1997 (c) Josephine M. Pace National Liirary Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services senrices bibliographiques 395 WelTmgtm Street 395, nie Wellington OttawaûN KlAON4 OitawaON KiAON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sell reproduire, prêter, distnher ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantie1s may be priuted or otheMrise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits saas son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to provide a comparative study of the soteriology of Julian of Norwich in fourteenth century England and that of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65).