John Wesley and Eastern Orthodoxy: Influences, Convergences and Differences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi: the Doctrine of the Theotokos As a Liturgical Creed in the Coptic Orthodox Church

Journal of Coptic Studies 14 (2012) 47–62 doi: 10.2143/JCS.14.0.2184687 LEX ORANDI, LEX CREDENDI: THE DOCTRINE OF THE THEOTOKOS AS A LITURGICAL CREED IN THE COPTIC ORTHODOX CHURCH BY BISHOY DAWOOD 1. Introduction In the Surah entitled “The Table Spread” in the Quran, Mohammed, the prophet of Islam, proclaimed a long revelation from God, and in a part that spoke of the role of Mary and teachings of Jesus, the following was mentioned: “And behold! Allah will say: ‘O Jesus the son of Mary! Did you say to men, ‘worship me and my mother as gods in derogation of Allah’?’” (Sura 5:116).1 It is of note here that not only the strict mono- theistic religion of Islam objected to the Christian worshipping of Jesus as God, but it was commonly believed that Christians also worshipped his mother, Mary, as a goddess. This may have been the result of a mis- understanding of the term Theotokos, literally meaning “God-bearer”, but also means “Mother of God”, which was attributed to Mary by the Christians, who used the phrase Theotokos in their liturgical worship. Likewise, in Protestant theology, there was a reaction to the excessive adoration of the Virgin Mary in the non-liturgical devotions of the churches of the Latin West, which was termed “Mariolatry.” However, as Jaroslav Pelikan noted, the Eastern churches commemorated and cel- ebrated Mary as the Theotokos in their liturgical worship and hymnology.2 The place of the Theotokos in the liturgical worship of the Eastern Chris- tian churches does not only show the spiritual relation between the Virgin Mother and the people who commemorate her, but it is primarily a creedal affirmation of the Christology of the believers praying those hymns addressed to the Theotokos. -

Soteriology 1 Soteriology

Soteriology 1 Soteriology OVERVIEW 2 Sin and Salvation 2 The Gospel 3 Three broad aspects 4 Justification 4 Sanctification 5 Glorification 6 ATONEMENT 6 General Results 6 Old Testament Background 6 Sacrifice of Jesus 7 Atonement Theories 9 Extent of the Atonement 10 Synthesis 11 FAITH AND GRACE 13 Types of Faith 13 Christian concept of Faith 14 Rev. J. Wesley Evans Soteriology 2 Grace 15 Nature of Grace 15 Types of Grace 15 Sufficient and Efficacious 15 General effects of Grace (acc. to Aquinas II.I.111.3) 16 THE SALVATION PROCESS 16 Overview Sin and Salvation General Principal: The nature of the problem determines the nature of the solution Problem (Sin related issues) Solution (Salvation) Broken relationship with God Reconciliation and Adoption Death of the Soul (Original Sin) Soul regenerated, allowing the will to seek God Humans under God’s judgment Promise of forgiveness and mercy Corruption of the world, broken Future New Creation relationship with the natural world Evil and unjust human systems Future inauguration of the Kingdom of God Temptation of Satan and fallen angels Future judgment on evil The list above of the sacraments is my own speculation, it seems to “fit” at this point. Rev. J. Wesley Evans Soteriology 3 The Gospel Mark 1:1 The beginning of the good news [ euvaggeli,ou ] of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. Luke 9:6 They departed and went through the villages, bringing the good news [euvaggelizo,menoi ] and curing diseases everywhere. Acts 5:42 And every day in the temple and at home they did not cease to teach and proclaim [ euvaggelizo,menoi ] Jesus as the Messiah. -

Comparative Soteriology and Logical Incompatibility

COMPARATIVE SOTERIOLOGY AND LOGICAL INCOMPATIBILITY by Shandon L. Guthrie INTRODUCTION There is a tremendous amount of material that could have been included in this work on comparative soteriology; Nonetheless, I will attempt to encompass a variety of religious belief systems. I have selected Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity as world-wide representatives of different schools of thought. (1) When we think of religion, (2) we normally conjure up images of rules and regulations. In fact, most religions are primarily centered on some principle or guideline to follow in order to sustain or create some type of welfare for the individual. For this reason religion ultimately represents the desired path of each person who holds to some type of religious system. This brings us to the concept of soteriology . The term soteriology refers to the method or system of how one ought to operate in order to maximize personal and/or corporate salvation. Salvation itself actually carries a variety of definitions; However, the most basic way of defining it is in terms of "deliverance" or "welfare." (3) The question that immediately comes to mind is, "What exactly is one being 'delivered' or 'saved' from?" Indeed, every religion carries its own system and interpretation on such matters as these. Therefore, we shall examine and analyze each soteriological system according to the respective religion and determine if any or all religions can be simultaneously true. JUDAISM Judaism, like many religions, is a religion stemming from a long history of war and slavery. The most known aspects of Judaism are the dietary regulations, cultural practices, and political practices. -

Eastern Orthodox Ecclesiologies in the Era of Confessionalism Heith

Eastern Orthodox Ecclesiologies in the Era of Confessionalism Heith-Stade, David Published in: Theoforum 2010 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Heith-Stade, D. (2010). Eastern Orthodox Ecclesiologies in the Era of Confessionalism. Theoforum, 41(3), 373- 385. https://www.academia.edu/1125117/Eastern_Orthodox_Ecclesiologies_in_the_Era_of_Confessionalism Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Theoþrum, 4l (2010), p. 37 3-385 Eastern Orthodox Ecclesiologies in the Era of Confessionalism "[I believeJ in one, holy, catholic and apostolic church." Creed -Nicaeno-Constantinopolitan DAVID HEITH-STADE Lund University, Sweden The Eastern Orthodox Church was a self-evident phenomenon in Byzantine society. -

The Death and Resurrection of Christ in the Soteriology

THE DEATH AND RESURRECTION OF CHRIST IN THE SOTERIOLOGY OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM by George H. Wright, Jr., A.B. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University in Partial Fulfillment of the Re quirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin July, 1966 PREFACE It i. quite evident that there ha. been a movement durinl the pa.t thirty years or .0 away hOll an empba.ia on the death of Chriat to a focus on the Re.urreetion, or at l.alt to an interpre- tatioo which .how. tb4t death and reaurnction are intell'&l1y one. Thia reDewed intereat in the ailDiflcan,ee of Chrht·. re.urrection ha. been the ocea.ion fora re-exaeinatlon of many, if not all, area. of theology, includinl the QY area of .otedology. Recent UM' have abo witn.... d a renewed inter•• t in Pattiatic studie.. Th. school of Antioch, In particular,. ha. belUD to be ••en in a more favorable 11Cht. Wlth rare exe.ptionl, the theololian. of thia .ehool hav., until r.cently, b.en totally for- lot ten or 41 __ i •••d a. heretie.. Th. critlci.. that was leveled malnly .t the extreme po.ition. tekeD by individual. luch a. Ne.toriu. haft overahadowed the coapletely ol'th04ox beUd. of many Antiochene theololian•• CBJ:e of the 1'8"00. for _kiDI thh .tudy .... to dileover what place the AntiocheD" live to Chri.t'. death and re.urrection in their teachine about the Redemption. Thh va. done not only out of an intere.t in the current .pha.h OIl the Re.urrection and in the Antiochene School, but ... -

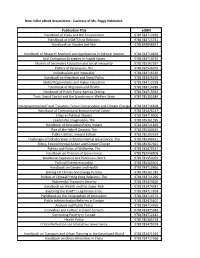

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Christianity In

CHRISTIANITY IN THE CONTEMPORARY MIDDLE EAS Venue: Mathematical Institute Presentations & Speakers Andrew Wiles Building Welcome - Martin Ganeri. O.R Vice regent, Radcliffe Observatory Quarter Blackfriars Hall, Oxford Woodstock Road Christianity in the Middle East - an Oxford, 0X2 6GG introduction and Overview - Anthony O'Mahony, Heythrop College, University of London Fee for the day (payable by cheque): £20 Christianity in Iraq: present situation and Includes lunch, tea & coffee future challenge - Professor Herman TeuleT Concessions on application. University of Louvain and Director. Institute for Registration deadline: Friday 24th Eastern Christianity October 2014 Coptic Christianity in Egypt today: reconfiguring power, religion and politics- To request a registration form please Dr Mariz Tadros, University of Sussex email Charlotte Redman: Armenian Christianity in the Middle East - [email protected] modern history and contemporary challenges - Dr Hratch Tchilingirian, Armenian Conference hosted by the Las Casas Institute, Studies, Oriental Institute, University of Oxford Blackfriars Hall, Oxford Erasing the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Greek Orthodox Christians in Turkey: «»pH^!^&£: Comparative lessons for Middle Eastern Christianity from the Turkish model of Religious Cleansing - Prof Elizabeth Prodrornou, Tufts University, Former Commissioner and vice-chair US Commission on International Religious freedom 2004-2012 & currently US Secretary of State Working Group on Religion and Foreign Policy Programme 'Christianity in -

Orthodox Christianity University of Pittsburgh Spring Term AY 2018-19 RELGST 1135 – 1150/SLAV 1135-1010 CRN: 25661

Orthodox Christianity University of Pittsburgh Spring Term AY 2018-19 RELGST 1135 – 1150/SLAV 1135-1010 CRN: 25661 Room: 213 CL Office: 835 Alumni Hall (inside suite 834) Meets: Mondays/Wednesdays 4:30-5:45 Office hours: Fridays 12pm – 1pm and by apt. Instructor: Dr. Joel Brady Course Description This course is designed as an overview of the history, teachings and rituals of Eastern Orthodox Christianity in its multinational context. Geographically, this context refers primarily to southeastern Europe, Russia and the coastal areas of the eastern Mediterranean, but there is also a significant Orthodox diaspora in the western hemisphere and in other parts of the world. We shall examine specific historical experience of Orthodox Christians in its Byzantine context, under Ottoman rule, in Slavic lands, under communism, and beyond. We consider the broader context of Eastern Christianity (including Oriental Orthodoxy, the Church of the East, and Eastern Catholicism), as well as relations with Western Catholic and Protestant Christianity, and other religions and systems of belief (e.g., Judaism, Islam, atheism). Through lectures, readings, discussions, films, and a field trip to a local Orthodox church, students will gain an insight into multifaceted world of Orthodox Christianity: its spiritual practices and rich artistic, musical and ritual expressions. Course Learning Objectives By the end of this course, you will be able to…. Identify key terms, concepts, themes, and people in the history of Orthodox Christianity and situate them within a broad temporal, geographical, and confessional framework. Articulate the connection(s) between Orthodox Christian doctrine and practice. Analyze the historical relationships and interactions between Eastern Orthodox Christianity, on the one hand, and on the other hand, other forms of Christianity, other religions, and various secular movements. -

Monastic Tradition in Eastern Christianity and the Outside Word

142 International Journal of Orthodox Theology 7:2 (2016) urn:nbn:de:0276-2016-2081 Ines Angeli Murzaku (ed.) Review: Monastic tradition in Eastern Christianity and the Outside Word. A Call for Dialogue Peters Leuven – Paris – Walpole, MA – 2013, pp. 286. Reviewed by Mihail-Liviu Dinu The present volume by its inner- essence of Christianity dialogue and by its ecumenical interdisci- plinary, lends itself to several conclusions, which must be Mihail-Liviu Dinu is PhD understood as multiple aspects Candidate at the Faculty of Orthodox Theology of the that create the image of what “December 1st 1918” Uni- Christian monastic tradition versity of Alba-Iulia, Roma- means in today’s word. nia, Erasmus Student at The present work is structured on Otto-Friedrich University of three vast chapters; each of them Bamberg, Germany Monastic tradition in Eastern Christianity 143 and the Outside Word. A Call for Dialogue tries to deliver the core aspects of understanding monasticism. It must be pointed out that the editor of this project, Ines Angeli Murzaku, a very well know American Professor of Ecclesiastical History, shows a real approach of the inter-Christianity and inter-religious dialogue, which has proved very fruitful in the inner-essence of Eastern Christianity. According to the editor, this project starts at the Greek monastery of Mother of God at Abbot of Grottaferrata, near the city of Rome, keeping in mind the words of Saint Cyprian of Carthage: “They do not speak great things, but live them”. The purpose of such a project, I believe, starts from the fact that monasticism is not a phenomenon particular to east of west Christianity. -

The Person of the Holy Spirit

The WORK of the Holy Spirit David J. Engelsma Herman Hanko Published by the British Reformed Fellowship, 2010 www.britishreformedfellowship.org.uk Printed in Muskegon, MI, USA Scripture quotations are taken from the Authorized (King James) Version Quotations from the ecumenical creeds, the Three Forms of Unity (except for the Rejection of Errors sections of the Canons of Dordt) and the Westminster Confession are taken from Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, 3 vols. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1966) Distributed by: Covenant Protestant Reformed Church 7 Lislunnan Road, Kells Ballymena, N. Ireland BT42 3NR Phone: (028) 25 891851 Website: www.cprc.co.uk E-mail: [email protected] South Holland Protestant Reformed Church 1777 East Richton Road Crete, IL 60417 USA Phone: (708) 333-1314 Website: www.southhollandprc.org E-mail: [email protected] Faith Protestant Reformed Church 7194 20th Avenue Jenison, MI 49418 USA Phone: (616) 457-5848 Website: www.faithprc.org Email: [email protected] Contents Foreword v PART I Chapter 1: The Person of the Holy Spirit 1 Chapter 2: The Outpouring of the Holy Spirit 27 Chapter 3: The Holy Spirit and the Covenant of Grace 41 Chapter 4: The Spirit as the Spirit of Truth 69 Chapter 5: The Holy Spirit and Assurance 84 Chapter 6: The Holy Spirit and the Church 131 PART II Chapter 7: The Out-Flowing Spirit of Jesus 147 Chapter 8: The Bride’s Prayer for the Bridegroom’s Coming 161 APPENDIX About the British Reformed Fellowship 174 iii Foreword “My Father worketh hitherto, and I work,” Jesus once declared to the unbelieving Jews at a feast in Jerusalem ( John 5:17). -

1 Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent Christians Believe That The

Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent1 Christians believe that the Persons of the Trinity are distinct but in every respect equal. We believe also that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father. It is difficult to reconcile claims about the Father’s role as the progenitor of Trinitarian Persons with commitment to the equality of the persons, a problem that is especially acute for Social Trinitarians. I propose a metatheological account of the doctrine of the Trinity that facilitates the reconciliation of these two claims. On the proposed account, “Father” is systematically ambiguous. Within economic contexts, those which characterize God’s relation to the world, “Father” refers to the First Person of the Trinity; within theological contexts, which purport to describe intra-Trinitarian relations, it refers to the Trinity in toto-- thus in holding that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father we affirm that the Trinity is the source and unifying principle of Trinitarian Persons. While this account solves a nagging problem for Social Trinitarians it is theologically minimalist to the extent that it is compatible with both Social Trinitarianism and Latin Trinitarianism, and with heterodox Modalist and Tri-theist doctrines as well. Its only theological cost is incompatibility with the Filioque Clause, the doctrine that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son—and arguably that may be a benefit. 1. Problem: the equality of Persons and asymmetry of processions In addition to the usual logical worries about apparent violations of transitivity of identity, the doctrine of the Trinity poses theological problems because it commits us to holding that there are asymmetrical quasi-causal relations amongst the Persons: the Father “begets” the Son and “spirates” the Holy Spirit. -

How to Acquire an Orthodox Phronêma in the West: from Ecclesiastical Enculturation to Theological Competence

Copyright © 2019 Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies. All Rights Reserved Logos: A Journal of Eastern Christian Studies Vol. 58 (2017) Nos. 1–4, pp. 251–279 How to Acquire an Orthodox Phronêma in the West: From Ecclesiastical Enculturation to Theological Competence Augustine Cassidy The Eastern churches have much to offer the West. By way of examples, I might list dignified and solemn worship, fi- delity to the apostles and their successors, a living witness of saints, rich piety, exuberant joy, irreproachable theology, mys- ticism grounded in a holistic view of this good creation, time- honoured disciplines for spiritual development, aesthetics that make present the holiness of God, ancient principles that lead to union with God, a profound sense of communal identity, compassionate understanding of sins coupled with the recogni- tion that sin is not central to human life, courage and perseve- rance in the face of oppression even unto martyrdom, unflin- ching opposition to heresy, and access to a wealth of theology not otherwise available. These blessings are not necessarily all equally available, nor are they presented as such by Eastern Christians, nor indeed are they all mutually consistent. Some are probably aspirations rather than realities. This is, in effect, to admit that my list is synthetic, uncritical, and indicative of what people have claimed to find in the Eastern churches. And a similar list could assuredly be populated with problems en- demic to the Eastern churches that no Westerner would find appealing or attractive in the least. But I begin with a register of the blessings that, having freely received, Eastern Christians freely give, since my purpose in this paper is to analyse some aspects of Western conversions to Eastern Christianity.