This Is a Repository Copy of Ben Jonson and Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Near & Middle East

February 2021 February The Near & Middle East A Short List of Books, Maps & Photographs Maggs Bros. Ltd. Maggs Bros. MAGGS BROS. LTD. 48 BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON WC1B 3DR & MAGGS BROS. LTD. 46 CURZON STREET LONDON W1J 7UH Our shops are temporarily closed to the public. However, we are still processing sales by our website, email and phone; and we are still shipping books worldwide. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7493 7160 Email: [email protected] Website: www.maggs.com Unless otherwise stated, all sales are subject to our standard terms of business, as displayed in our business premises, and at http://www.maggs.com/terms_and_conditions. To pay by credit or debit card, please telephone. Cover photograph: item 12, [IRAQ]. Cheques payable to Maggs Bros Ltd; please enclose invoice number. Ellipse: item 21, [PERSIA]. THE ARABIAN PENINSULA Striking Oil in Abu Dhabi 1 [ABU DHABI]. VARIOUS AUTHORS. A collection of material relating to the discovery of oil in Abu Dhabi. [Including:] ABU DHABI MARINE AREAS LTD. Persian Gulf Handbook. Small 8vo. Original green card wrappers, stapled, gilt lettering to upper wrapper; staples rusted, extremities bumped, otherwise very good. [1], 23ff. N.p., n.d., but [Abu Dhabi, c.1954]. [With:] GRAVETT (Guy). Fifteen original silver-gelatin photographs, mainly focusing on the inauguration of the Umm Shaif oilfield. 9 prints measuring 168 by 216mm and 6 measuring 200 by 250mm. 14 with BP stamps to verso and all 15 have duplicated typescript captions. A few small stains, some curling, otherwise very good. Abu Dhabi, 1962. [And:] ROGERS (Lieut. Commander J. A.). OFF-SHORE DRILLING. -

The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack

TTHHEE GGUUNNPPOOWWDDEERR PPLLOOTT The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack Welcome to Heritage Doncaster’s the Gunpowder Plot activity pack. This booklet is filled with ideas that you can have a go at as a family at home whilst learning about the Gunpowder Plot. Some of these activities will require adult supervision as they require using an oven, a sharp implement, or could just be a bit tricky these have been marked with this warning triangle. We would love to see what you create so why not share your photos with us on social media or email You can find us at @doncastermuseum @DoncasterMuseum [email protected] Have Fun! Heritage Doncaster Education Service Contents What was the Gunpower Plot? Page 3 The Plotters Page 4 Plotters Top Trumps Page 5-6 Remember, remember Page 7 Acrostic poem Page 8 Tunnels Page 9 Build a tunnel Page 10 Mysterious letter Page 11 Letter writing Page 12 Escape and capture Page 13 Wanted! Page 14 Create a boardgame Page 15 Guy Fawkes Night Page 16 Firework art Page 17-18 Rocket experiment Page 19 Penny for a Guy Page 20 Sew your own Guy Page 21 Traditional Bonfire Night food Page 22 Chocolate covered apples Page 23 Wordsearch Page 24 What was the Gunpowder Plot? The Gunpowder Plot was a plan made by thirteen men to blow up the Houses of Parliament when King James I was inside. The Houses of Parliament is an important building in London where the government meet. It is made up of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. -

The History of the Jamestown Colony: Seventeenth-Century and Modern Interpretations

The History of the Jamestown Colony: Seventeenth-Century and Modern Interpretations A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of the Ohio State University By Sarah McBee The Ohio State University at Mansfield June 2009 Project Advisor: Professor Heather Tanner, Department of History Introduction Reevaluating Jamestown On an unexceptional day in December about four hundred years ago, three small ships embarked from an English dock and began the long and treacherous voyage across the Atlantic. The passengers on board envisioned their goals – wealth and discovery, glory and destiny. The promise of a new life hung tantalizingly ahead of them. When they arrived in their new world in May of the next year, they did not know that they were to begin the journey of a nation that would eventually become the United States of America. This summary sounds almost ridiculously idealistic – dream-driven achievers setting out to start over and build for themselves a better world. To the average American citizen, this story appears to be the classic description of the Pilgrims coming to the new world in 1620 seeking religious freedom. But what would the same average American citizen say to the fact that this deceptively idealistic story actually took place almost fourteen years earlier at Jamestown, Virginia? The unfortunate truth is that most people do not know the story of the Jamestown colony, established in 1607.1 Even when people have heard of Jamestown, often it is with a negative connotation. Common knowledge marginally recognizes Jamestown as the colony that predates the Separatists in New England by more than a dozen years, and as the first permanent English settlement in America. -

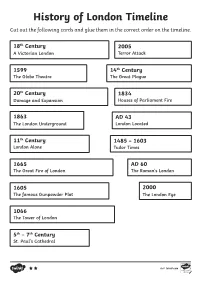

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

History of the Gunpowder Plot & Guy Fawkes Night Four Hundred Years Ago, in 1605, a Man Called Guy Fawkes and a Group Of

History of the Gunpowder Plot & Guy Fawkes Night Four hundred years ago, in 1605, a man called Guy Fawkes and a group of plotters attempted to blow up the Houses of Parliament in London with barrels of gunpowder placed in the basement. They wanted to kill King James and the king’s leaders. Houses of Parliament, London Why did Guy Fawkes want to kill King James 1st and the king’s leaders? When Queen Elizabeth 1st took the throne of England she made some laws against the Roman Catholics. Guy Fawkes was one of a small group of Catholics who felt that the government was treating Roman Catholics unfairly. They hoped that King James 1st would change the laws, but he didn't. Catholics had to practise their religion in secret. There were even fines for people who didn't attend the Protestant church on Sunday or on holy days. James lst passed more laws against the Catholics when he became king. What happened - the Gunpowder Plot A group of men led by Robert Catesby, plotted to kill King James and blow up the Houses of Parliament, the place where the laws that governed England were made. Guy Fawkes was one of a group of men The plot was simple - the next time Parliament was opened by King James l, they would blow up everyone there with gunpowder. The men bought a house next door to the parliament building. The house had a cellar which went under the parliament building. They planned to put gunpowder under the house and blow up parliament and the king. -

Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015)

FINDLEY JR, JAMES WALTER, Ph.D. “Went to Build Castles in the Aire:” Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015). Directed by Dr. Phyllis Whitman Hunter. 266pp. This study examines the early phases of Anglo-North American colonization from 1570 to 1640 by employing the lenses of imagination and failure. I argue that English colonial projectors envisioned a North America that existed primarily in their minds – a place filled with marketable and profitable commodities waiting to be extracted. I historicize the imagined profitability of commodities like fish and sassafras, and use the extreme example of the unicorn to highlight and contextualize the unlimited potential that America held in the minds of early-modern projectors. My research on colonial failure encompasses the failure of not just physical colonies, but also the failure to pursue profitable commodities, and the failure to develop successful theories of colonization. After roughly seventy years of experience in America, Anglo projectors reevaluated their modus operandi by studying and drawing lessons from past colonial failure. Projectors learned slowly and marginally, and in some cases, did not seem to learn anything at all. However, the lack of learning the right lessons did not diminish the importance of this early phase of colonization. By exploring the variety, impracticability, and failure of plans for early settlement, this study investigates the persistent search for usefulness of America by Anglo colonial projectors in the face of high rate of -

Guided Cycle Ride

Cyclesolihull Routes Cyclesolihull Rides short route from Cycling is a great way to keep fit whilst at Cyclesolihull offers regular opportunities to S1 the same time getting from A to B or join with others to ride many of the routes in Dorridge exploring your local area. this series of leaflets. The rides are organised This series of routes, developed by by volunteers and typically attract between 10 and 20 riders. To get involved, just turn up and Cyclesolihull will take you along most of ride! the network of quiet lanes, roads and cycle paths in and around Solihull, introducing Sunday Cycle Rides take place most Cyclesolihull Sunday afternoons at 2 pm from April to you to some places you probably didn’t Explore your borough by bike even know existed! September and at 1.30 pm from October to March. One of the routes will be followed with a The routes have been carefully chosen to mixture of route lengths being ridden during avoid busier roads so are ideal for new each month. In autumn and winter there are cyclists and children learning to cycle on more shorter rides to reflect the reduced daylight hours. One Sunday each month in the road with their parents. spring and summer the ride is a 5 mile Taster You can cycle the routes alone, with family Ride. This is an opportunity to try a and friends, or join other people on one of Cyclesolihull ride without going very far and is the regular Cyclesolihull rides. an ideal introduction to the rides, especially for new cyclists and children. -

The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622

The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622 Matthew John Sparacio Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Crandall A. Shifflett, Chair A. Roger Ekirch Brett L. Shadle 16 March 2010 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Early Modern England; Colonial Virginia; Jamestown; Devil; Fear Copyright 2010, Matthew John Sparacio The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622 Matthew John Sparacio ABSTRACT This study examines the role of emotions – specifically fear – in the development and early stages of settlement at Jamestown. More so than any other factor, the Protestant belief system transplanted by the first settlers to Virginia helps explain the hardships the English encountered in the New World, as well as influencing English perceptions of self and other. Out of this transplanted Protestantism emerged a discourse of fear that revolved around the agency of the Devil in the temporal world. Reformed beliefs of the Devil identified domestic English Catholics and English imperial rivals from Iberia as agents of the diabolical. These fears travelled to Virginia, where the English quickly ʻsatanizedʼ another group, the Virginia Algonquians, based upon misperceptions of native religious and cultural practices. I argue that English belief in the diabolic nature of the Native Americans played a significant role during the “starving time” winter of 1609-1610. In addition to the acknowledged agency of the Devil, Reformed belief recognized the existence of providential actions based upon continued adherence to the Englishʼs nationally perceived covenant with the Almighty. -

J?, ///? Minor Professor

THE PAPAL AGGRESSION! CREATION OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 APPROVED! Major professor ^ J?, ///? Minor Professor ItfCp&ctor of the Departflfejalf of History Dean"of the Graduate School THE PAPAL AGGRESSION 8 CREATION OP THE SOMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For she Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Denis George Paz, B. A, Denton, Texas January, 1969 PREFACE Pope Plus IX, on September 29» 1850, published the letters apostolic Universalis Sccleslae. creating a terri- torial hierarchy for English Roman Catholics. For the first time since 1559» bishops obedient to Rome ruled over dioceses styled after English place names rather than over districts named for points of the compass# and bore titles derived from their sees rather than from extinct Levantine cities« The decree meant, moreover, that6 in the Vati- k can s opinionc England had ceased to be a missionary area and was ready to take its place as a full member of the Roman Catholic communion. When news of the hierarchy reached London in the mid- dle of October, Englishmen protested against it with unexpected zeal. Irate protestants held public meetings to condemn the new prelates» newspapers cried for penal legislation* and the prime minister, hoping to strengthen his position, issued a public letter in which he charac- terized the letters apostolic as an "insolent and insidious"1 attack on the queen's prerogative to appoint bishops„ In 1851» Parliament, despite the determined op- position of a few Catholic and Peellte members, enacted the Ecclesiastical Titles Act, which imposed a ilOO fine on any bishop who used an unauthorized territorial title, ill and permitted oommon informers to sue a prelate alleged to have violated the act. -

"Anthony Rivers" and the Appellant Controversy, 1601-2 John M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Notre Dame Law School: NDLScholarship Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2006 The ecrS et Sharers: "Anthony Rivers" and the Appellant Controversy, 1601-2 John M. Finnis Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Patrick Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation John M. Finnis & Patrick Martin, The Secret Sharers: "Anthony Rivers" and the Appellant Controversy, 1601-2, 69 Huntington Libr. Q. 195 (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/681 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Secret Sharers: “Anthony Rivers” and the Appellant Controversy, 1601–2 Author(s): Patrick Martin and and John Finnis Source: Huntington Library Quarterly, Vol. 69, No. 2 (June 2006), pp. 195-238 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/hlq.2006.69.2.195 . Accessed: 14/10/2013 09:19 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. -

Gunpowder, Treason and Plot (Gunpowder Plot) Teacher Notes

Gunpowder, Treason and Plot (Gunpowder Plot) Teacher notes Duration: 45 minutes Meeting Point: Salt Tower Courtyard Why did the Gunpowder Plot fail? Explore the story of Guy Fawkes' plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament – and visit the prison cells that housed his fellow conspirators. Join a costumed presenter, portraying one of King James' courtiers, who will take you to a number of sites within the Tower that hold particular relevance for the plot of 1605. Learning objectives Children will: Learn key features of the Gunpowder Plot through questioning and participation. Compare and contrast life today with life in the 1600s. Develop historical enquiry skills and an understanding of chronology. National Curriculum links This session supports: Extending chronological knowledge of significant events in British history beyond 1066. Development of asking perceptive questions by exploring differing representations of a key historical figure. During your session: Please note that the 1:5 staff to child ratio which we ask for throughout your visit still applies during your learning session. We ask that sufficient adults remain with the group as they will be encouraged to join in with the session activities. For Health & Safety reason, our sessions are for a maximum of 35 children. The education session your group has booked with us takes place on the visitor route at the Tower of London. Please meet your session presenter at the Salt Tower Courtyard. This is marked on the map below with a star. The courtyard is located next to the New Armouries Cafe. This is the New Armouries Cafe This is the Salt Tower Courtyard Enter here This is where your costumed session presenter will meet you at your allocated start time. -

James I and Gunpowder Treason Day.', Historical Journal., 64 (2)

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 01 October 2020 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Williamson, P. and Mears, N. (2021) 'James I and Gunpowder treason day.', Historical journal., 64 (2). pp. 185-210. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X20000497 Publisher's copyright statement: This article has been published in a revised form in Historical Journal https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X20000497. This version is published under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND. No commercial re-distribution or re-use allowed. Derivative works cannot be distributed. c The Author(s) 2020. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk JAMES I AND GUNPOWDER TREASON DAY* PHILIP WILLIAMSON AND NATALIE MEARS University of Durham Abstract: The assumed source of the annual early-modern English commemoration of Gunpowder treason day on 5 November – and its modern legacy, ‘Guy Fawkes day’ or ‘Bonfire night’ – has been an act of parliament in 1606.