Mcgill University Health Centre Montreal, Qc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advancing Health Care

Centre universitaire de santé McGill McGill University Health Centre Advancing Health Care Annual Report | 2 0 0 8 - 2 0 0 9 Table of Contents The Best Care for Life 1 Message from the Chairman of the Board of Directors 2 Message from the Director General and CEO 3 Vision, Mission, Values 4 Stats at a Glance 5 2008-2009 Year in Review 6-7 Clinical & Research Firsts 8-9 Advancing Health Care 10-11 Home-based care improving quality of life... 12-13 Nationwide leading pain program providing relief… 14-15 Maintaining quality of life as long as possible… 16-17 Advances in cardiac care paving bright futures… 18-19 Patient care always one step ahead… 20-21 New technology breaking down barriers… 22-23 Research 24-25 Teaching 26-27 The Redevelopment Project 28-29 Foundations 30-31 Auxiliaries & Volunteers 32-33 Awards & Honours 34-35 Board of Directors 36 Financial Results 37-40 Financial Data 41 Statistical Data 42-43 Acknowledgements 44 Annual Report 2008-2009 The Best Care For Life The McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) is a comprehensive academic health institution with an international reputation for excellence in clinical programs, research and teaching. Its partner hospitals are the Montreal Children’s, the Montreal General, the Royal Victoria, the Montreal Neurological Hospital/Institute, the Montreal Chest Institute as well as the Lachine Hospital and Camille- Lefebvre Pavillion. Building on our tradition of medical leadership, the MUHC continues to shape the course of academic medicine by attracting clinical and research authorities from around the world, by training the next generation of medical professionals, and continuing to provide the best care for life to people of all ages. -

The West Island Health and Social Services Centre

2011 Directory www.westislandhssc.qc.ca The West Island Health and Social Services Centre This brochure was produced by the West Island Health and Social Services Centre (HSSC). The "Access to Health Care in your Neighbourhood" brochure presents the main health and social services available near you. The West Island HSSC was created in 2004. It is comprised of the Lakeshore General Hospital, the CLSC de Pierrefonds, the CLSC du Lac‐ Saint‐Louis and the Centre d’hébergement Denis‐Benjamin‐Viger (a residential and long‐term care centre). The HSSC works closely with the medical clinics and community organizations within its territory. Its mission is to: • Help you obtain the health and social services you need as soon as possible. • Offer high‐quality services to its users and the residents of its residential and long‐term care centre. • Encourage you to adopt a healthy lifestyle. • Contribute, with its local and regional partners, to the improvement of the health of the population within its territory. With some 2000 employees, more than 250 doctors and an annual budget of $150M, it plays a leading role in the economic and community life of your neighbourhood. The West Island HSSC is a member of the Montreal Network of Health Promoting Hospitals and HSSCs, which is affiliated with the World Health Organization (WHO). There are many community organizations in your neighbourhood that work with health network institutions. For more information on these organizations, or to learn about health and social resources available in your community, visit the Health Care Access in Montreal portal at http://www.santemontreal.qc.ca/english, contact the Information and Referral Centre of Greater Montreal at 514‐527‐1375 or contact your CLSC. -

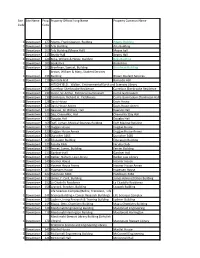

Site Code Site Name Prop. Code Property Official Long Name Property Common Name 1 Downtown 177 Adams, Frank Dawson, Building

Site Site Name Prop. Property Official Long Name Property Common Name Code Code 1 Downtown 177 Adams, Frank Dawson, Building Adams Building 1 Downtown 103 Arts Building Arts Building 1 Downtown 103 Arts Building (Moyse Hall) Moyse hall 1 Downtown 113 Beatty Hall Beatty Hall 1 Downtown 124 Birks, William & Henry, Building Birks Building 1 Downtown 185 Bookstore Bookstore 1 Downtown 102 Bronfman, Samuel, Building Bronfman Building Brown, William & Mary, Student Services 1 Downtown 236 Building Brown Student Services 1 Downtown 110 Burnside Hall Burnside Hall HITSCHFIELD, Walter, Environmental Earth and Sciences Library 1 Downtown 251 Carrefour Sherbrooke Residence Carrefour Sherbrooke Residence 1 Downtown 139 Currie, Sir Arthur, Memorial Gymnasium Currie Gymnasium 1 Downtown 139 Tomlinson, Richard H. Fieldhouse Currie Gymnasium (Tomlinson Hall) 1 Downtown 128 Davis House Davis House 1 Downtown 224 Davis House Annex Davis House Annex 1 Downtown 123 Dawson, Sir William, Hall Dawson Hall 1 Downtown 122 Day, Chancellor, Hall Chancellor Day Hall 1 Downtown 125 Douglas Hall Douglas Hall 1 Downtown 169 Duff, Lyman, Medical Sciences Building Duff Medical Building 1 Downtown 127 Duggan House Duggan House 1 Downtown 223 Duggan House Annex Duggan House Annex 1 Downtown 249 Durocher 3465 Durocher 3465 1 Downtown 168 Education Building Education Building 1 Downtown 129 Faculty Club Faculty Club 1 Downtown 197 Ferrier, James, Building Ferrier Building 1 Downtown 133 Gardner Hall Gardner Hall 1 Downtown 231 Gelber, Nahum, Law Library Gelber Law Library 1 Downtown 149 Hosmer House Hosmer House 1 Downtown 132 Hosmer House Annex Hosmer House Annex 1 Downtown 167 Hugessen House Hugessen House 1 Downtown 222 Hutchison 3464 Hutchison 3464 1 Downtown 112 James, F. -

Health Sciences Programs, Courses and University Regulations 2015-2016

Health Sciences Programs, Courses and University Regulations 2015-2016 This PDF excerpt of Programs, Courses and University Regulations is an archived snapshot of the web content on the date that appears in the footer of the PDF. Archival copies are available at www.mcgill.ca/study. This publication provides guidance to prospects, applicants, students, faculty and staff. 1 . McGill University reserves the right to make changes to the information contained in this online publication - including correcting errors, altering fees, schedules of admission, and credit requirements, and revising or cancelling particular courses or programs - without prior notice. 2 . In the interpretation of academic regulations, the Senate is the ®nal authority. 3 . Students are responsible for informing themselves of the University©s procedures, policies and regulations, and the speci®c requirements associated with the degree, diploma, or certi®cate sought. 4 . All students registered at McGill University are considered to have agreed to act in accordance with the University procedures, policies and regulations. 5 . Although advice is readily available on request, the responsibility of selecting the appropriate courses for graduation must ultimately rest with the student. 6 . Not all courses are offered every year and changes can be made after publication. Always check the Minerva Class Schedule link at https://horizon.mcgill.ca/pban1/bwckschd.p_disp_dyn_sched for the most up-to-date information on whether a course is offered. 7 . The academic publication year begins at the start of the Fall semester and extends through to the end of the Winter semester of any given year. Students who begin study at any point within this period are governed by the regulations in the publication which came into effect at the start of the Fall semester. -

Faculty of Medicine Programs, Courses and University Regulations 2017-2018

Faculty of Medicine Programs, Courses and University Regulations 2017-2018 This PDF excerpt of Programs, Courses and University Regulations is an archived snapshot of the web content on the date that appears in the footer of the PDF. Archival copies are available at www.mcgill.ca/study. This publication provides guidance to prospects, applicants, students, faculty and staff. 1 . McGill University reserves the right to make changes to the information contained in this online publication - including correcting errors, altering fees, schedules of admission, and credit requirements, and revising or cancelling particular courses or programs - without prior notice. 2 . In the interpretation of academic regulations, the Senate is the ®nal authority. 3 . Students are responsible for informing themselves of the University©s procedures, policies and regulations, and the speci®c requirements associated with the degree, diploma, or certi®cate sought. 4 . All students registered at McGill University are considered to have agreed to act in accordance with the University procedures, policies and regulations. 5 . Although advice is readily available on request, the responsibility of selecting the appropriate courses for graduation must ultimately rest with the student. 6 . Not all courses are offered every year and changes can be made after publication. Always check the Minerva Class Schedule link at https://horizon.mcgill.ca/pban1/bwckschd.p_disp_dyn_sched for the most up-to-date information on whether a course is offered. 7 . The academic publication year begins at the start of the Fall semester and extends through to the end of the Winter semester of any given year. Students who begin study at any point within this period are governed by the regulations in the publication which came into effect at the start of the Fall semester. -

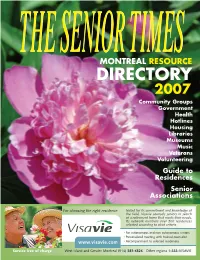

T Dir 2006 Frontpage

ST Dir_07 frontpage.qxp:ST Dir_07 frontpage 6/19/07 12:21 PM Page 1 THE SENIOR TIMES MONTREAL RESOURCE DIRECTORY 2007 Community Groups Government Health Hotlines Housing Libraries Museums Music Veterans Volunteering Guide to Residences Senior Associations For choosing the right residence Noted for its commitment and knowledge of the field, Visavie counsels seniors in search of a retirement home that meets their needs. Its network numbers over 500 residences selected according to strict criteria. • For autonomous and non autonomous seniors • Personalized meeting with trained counselor www.visavie.com • Accompaniment to selected residences Service free of charge West Island and Greater Montreal (514) 383-6826 Other regions 1-888-VISAVIE ST_Dir06 p02_08_c.qxp 6/19/07 4:29 PM Page 2 2 • THE SENIOR TIMES • MONTREAL RESOURCE DIRECTORY • 2007 ST_Dir06 p02_08_c.qxp 6/19/07 5:38 PM Page 3 TAXIS 24-Hour Service ◆ In business since 1922 ◆ Fast and courteous service ◆ Reservations accepted ◆ Special care for elderly and handicapped ◆ Fast and safe delivery of packages ◆ Acceptance of coupons from Diamond, Veterans & Candare ◆ Largest fleet of vehicles on the Montreal Island 2007 CREDIT CARDS ACCEPTED GOLD DIAMOND 514 273-6331 2007 • THE SENIOR TIMES • MONTREAL RESOURCE DIRECTORY • 3 ST_Dir06 p02_08_c.qxp 6/19/07 5:41 PM Page 4 CALDWELL RESIDENCES Why live ALONE? Caldwell Residences offers subsidized housing within a safe community environment to independent people who are 60 years and over with a low to moderate income. Our buildings are in Côte St. -

Brett D. Thombs, Ph.D

McGill University, Faculty of Medicine Curriculum Vitae Date of Last Revision: March 18, 2019 A. IDENTIFICATION Name: Brett D. Thombs, Ph.D. Address: Jewish General Hospital, 4333 Cote Ste. Catherine Road, Montreal, QC, H3T 1E4 Telephone: (514) 340-8222 ext. 5112 E-mail: [email protected] B. EDUCATION Post-doctoral fellowship, Clinical Health Psychology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Supervisor: Dr. James A. Fauerbach. 2004-2005. MA, PhD, Clinical Psychology, Fordham University, Bronx, New York, USA. Doctoral Thesis: Measurement invariance of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire across gender and race/ethnicity: applications of structural equation modeling and item response theory. Supervisors: Dr. Charles Lewis and Dr. David P. Bernstein. 1999-2004. MA, Special Education, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA. Supervisor: Dr. Aldine Von Isser.1994-1995. BA, Economics and the Honors Program in Mathematical Methods in the Social Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA. Supervisor: Dr. Michael F. Dacey. 1985-1989. C. APPOINTMENTS University Professor with Tenure, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2015- present. Associate Professor with Tenure (early), Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2011-2015. Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2006- 2011. Associate Member, Biomedical Ethics Unit (Faculty of Medicine), McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2017-present. Associate Member, Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2013- present. Associate Member, Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2011-present. Associate Member, School of Nursing, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2011-2016. Associate Member, Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. -

Annual Report 2007-2008 Table of Contents the Best Care for Life

The MUHC. We’re all about people Centre universitaire de santé McGill McGill University Health Centre Annual Report 2007-2008 Table of contents The Best Care For Life Annual Report 2007-2008 Centre universitaire de santé McGill Introduction McGill University Health Centre Best Care For Life 2 Canada’s Top 100 Employers 3 Message from the Chair of the Board of Directors 4 The McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) is one of the most comprehensive academic health centres in North America. Mission, Vision, Values 5 The MUHC represents five teaching hospitals affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine of McGill University: The Montreal Children’s, Montreal General, Royal Victoria, and Montreal Neurological hospitals, as well as The Montreal Chest Institute. Message from the Director General and CEO 6 The most recent member of the MUHC is The Lachine Hospital and Camille-Lefebvre Pavillion. Building on the tradition of 2007-2008 The Year in Review 7 medical leadership of these founding hospitals, the MUHC continues to shape the course of academic medicine by attracting clinical and research authorities from around the world and by training the next generation of medical professionals. And it continues to provide the best care for life to patients of all ages. The MUHC – We’re All About People 9 Transplant – the gift of life 11 MAUDE Unit – options for high-risk heart patients 13 John A. Rae, chair of the Best Care For Life campaign, explains how your MCH Insulin Pump Centre – helping kids be kids 15 donations can make a real difference to health care in Montreal. -

Annual Report 2020-2021

ANNEX 2 MCGILL UNIVERSITY HEALTH CENTRE USERS’ / PATIENTS’ COMMITTEE (MUHC UC/PC) 2020-2021 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSTITUTION 3 2. MESSAGE FROM THE CO-CHAIRS 4 3. PRIORITIES AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE PAST YEAR 5 4. THE COMMITTEE AND ITS MEMBERS 6 5. CONTACT INFORMATION 7 6. ACTIVITIES OF THE MUHC UC/PC 8 7. MUHC UC/PC MEETINGS 11 8. COLLABORATION WITH THE OTHER ACTORS IN COMPLAINT EXAMINATION SYSTEM 11 9. GOALS ESTABLISHED FOR NEXT YEAR 13 10. CONCLUSION (ISSUES, RECOMMENDATIONS AND PROJECTS 13 11. FINANCIAL REPORT 14 12. ACTIVITIES OF THE RESIDENTS’ COMMITTEE OF THE CAMILLE-LEFEBVRE PAVILION 14 2 1. INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSTITUTION The McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) is a non-merged institution. The MUHC is comprised of the: Allan Memorial Institute - Allan Lachine Hospital and Camille Lefebvre Pavilion - Lachine Montreal General Hospital - MGH Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital - Neuro MUHC Reproductive Centre And the Glen Site: Cedars Cancer Centre - CCC McGill Academic Eye Centre - MAEC Montreal Chest Institute - MCI Montreal Children’s Hospital - MCH Research Institute - RI Royal Victoria Hospital - RVH 3 2. MESSAGE FROM THE CO-CHAIRS The year 2020-2021 will long be remembered by MUHC patients and the MUHC Patients' Committee. The pandemic has disrupted the MUHC's normal operations and its ability to provide services to the population. The Patients' Committee would like to sincerely thank all MUHC staff and administration for their determination and resilience during this exceptional year. Despite the difficult context, the Patients' Committee has continued to respond to the increased requests from patients who have been experiencing multiple difficulties in obtaining appointments, in contacting clinics, in dealing with surgery postponements, in communicating with or visiting loved ones who were hospitalized, in obtaining news on their health status, and in fulfilling their duties as caregivers for Camille-Lefebvre residents. -

Mcgill University Health Centre 2016-2018 Action Plan Regarding People with Disabilities

MCGILL UNIVERSITY HEALTH CENTRE 2016-2018 ACTION PLAN REGARDING PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES PREAMBLE By virtue of article 61.1 of the Act to Secure Handicapped Persons in the Exercise of Their Rights With a View to Achieving Social, School and Workplace Integration, the Ministries, the vast majority of public bodies, including healthcare institutions, as well as municipalities of more than 15,000 people, must create, adopt, and publicize an action plan regarding people with disabilities. More specifically, the law provides that this action plan must be based on identified and noted obstacles to the integration of disabled people and must expressly lay out what measures will be taken to overcome them in the coming years. This approach should be understood to be a continuous and evolving process. 1 OVERVIEW OF THE MUHC The McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) is among the leading university health centres offering tertiary and quaternary (complex) care. Following in the tradition of medical leadership established by its founding hospitals, the MUHC offers multidisciplinary care of exceptional quality, centered on the needs of the patient and in a bilingual environment. Affiliated with McGill University's Faculty of Medicine, the MUHC contributes to the evolution of both pediatric and adult medicine by attracting clinical and research leaders from all over the world, evaluating cutting-edge medical technologies, and training tomorrow's healthcare professionals. In collaboration with our network partners, we are building a better future for our patients and their families; for our employees, professionals, researchers and students; for our community and above all, for life. Our mission is fourfold: Clinical Care, Research, Teaching and Health technology assessment OUR VISION As one of the world's foremost academic health centres, the MUHC will assure exceptional and integrated patient-centric care, research, teaching and technology assessment. -

In Focus NURSING AUTUMN 2010

in Focus NURSING AUTUMN 2010 McGill Building on Strengths IN THIS ISSUE 2 A Word From the Director 4 A Word From the Alumnae President 4 Letter to the Editor 5 School Successes Full accreditation for undergrad programs A novel critical care experience for undergrads International connections The School’s new learning lab Colleagueship events 11 Building on Research Strengths Nursing innovation at the MUHC Bridging the research-practice gap at the Jewish General Hospital 14 Celebrating People Celeste Johnston Elizabeth Logan Norma Ponzoni Outstanding students, faculty, staff, alumnae 21 Alumnae News Recollections from the 1970s Psychogeriatric nursing in the community We have heard from… In memoriam AN ANNUAL PUBLICATION FOR THE MCGILL SCHOOL OF NURSING ALUMNAE COMMUNITY McGill School of Nursing Autumn 2010 A Word From the Director Editorial Committee Hélène Ezer, N, PhD H é l è n e E z e r Margie Gabriel, BA Editing Jane Broderick Every academic year brings a unique set of Design & Layout challenges and, happily, a unique list of Cait Beattie accomplishments. The year 2009–10 was no exception. A number of major activities and Photo Retouch events took place at the School of Nursing Jean Louis Martin that reflect not only the achievements of Contributors individuals but also the accomplishments Ora Alberton, N, MScA of people working together to bring about Grace Bavington, BN change. It is time to celebrate our successes Rachel Boissonneault, N, BScN and to acknowledge the dedication and Stephanie Bouris, BSc commitment of all those who have made Madeleine Buck, N, MScA them possible. Franco A. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Qutayba Hamid NATIONALITY: Canadian QUALIFICATIONS: MB ChB Mosul University (1978) PhD (Faculty of Medicine), Univ. of London, UK FRC Path (Fellow of the Royal College of Pathologists), London, UK MRCP (Member of the Royal College of Physicians), London, UK FRCP (Fellow, Royal College of Physicians), Canada FRS (Fellow, Royal Society of Canada) APPOINTMENTS: Current Appointment: September 2017 – to date: Vice Chancellor for Medical and Health Sciences Colleges, and Dean of College of Medicine, University of Sharjah September 2015 – Sep 2017: Dean of College of Medicine, Univeristy of Sharjah October 2014 – Sept 2016: Special Advisor, International Initiatives Faculty of Medicine, McGill University January 2010 - Associate Director, Recruitment and Career Development September 2015: McGill University Health Centre Research Institute October 2008 - Director, Meakins-Christie Laboratories September 2016: McGill University September 2005 –Sept 2015: MUHC Strauss Chair in Respiratory Medicine McGill University Health Center January 2001- 2015: James McGill Professor of Medicine and Pathology McGill University June 1998- 2015: Professor of Medicine and Pathology McGill University (Full Professor with tenure since 1997) February 1999-2010: Director, Respiratory Axis McGill University Health Centre June 1993 – 2008: Research Director, Meakins-Christie Laboratories McGill University June 1993 - May 1998: Associate Professor of Medicine and Pathology, McGill University 1 June 1993 - April 2001: Service Director, , Royal Victoria Hosp., Attending Staff, Dept. of Medicine, Royal Victoria Hospital February 1996 - 2000: Associate Scientific Director, Respiratory Health- Network of Centres of Excellence (Inspiraplex), Montreal Chest Institute PREVIOUS APPOINTMENTS IN THE U.K. (1984-1993): 1984-1988: Fellow, Histochemistry Unit, RPMS Hammersmith Hospital, London, U.K. Oct 1988-Nov 1989: Lecturer, National Heart and Lung Institute, Brompton Hospital, London, U.K.