Dunblane Cathedral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE STAINED GLASS WINDOWS of St Andrew's Frognal United Reformed Church

THE STAINED GLASS WINDOWS of St Andrew’s Frognal United Reformed Church Finchley Road, Hampstead THE STAINED GLASS OF ST ANDREW’S FROGNAL A stained glass window consists of pieces of glass coloured THE ARTISTS through their mass, often with painted lines burnt in, all joined J Dudley Forsyth. He was active primarily in the 1920s. His together with grooved leads. Stained glass did not exist before studio was in Finchley Road near to St Andrew’s church, and Christian times and remains an essentially Christian art form. Its he was a manufacturer of stained glass rather than a main feature is that it relies on light passing through it at designer. His glass was used in some windows in different times of day. It was, and remains, a means of Westminster Abbey and the Baltic Exchange. communicating visually the Bible stories and Christian truth. William Morris of Westminster (1874-1944). A traditional However, the designers and glaziers saw stained glass as much artist who is not to be confused with the more famous more than a new art form. To them it was a physical socialist and craftsman of the same name. Active in London manifestation of God as Light, and, specifically, of Jesus being and the Home Counties. the Light of the World. The church building became envisaged Henry James Salisbury (1864-1916). He was a Methodist from more and more as a house of colours, a place filled with light for Harpenden who had studios in Knightsbridge and St the greater glory of God. And the very Scriptures themselves Albans. -

Catalogue Description and Inventory

= CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION AND INVENTORY Adv.MSS.30.5.22-3 Hutton Drawings National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © 2003 Trustees of the National Library of Scotland = Adv.MSS.30.5.22-23 HUTTON DRAWINGS. A collection consisting of sketches and drawings by Lieut.-General G.H. Hutton, supplemented by a large number of finished drawings (some in colour), a few maps, and some architectural plans and elevations, professionally drawn for him by others, or done as favours by some of his correspondents, together with a number of separately acquired prints, and engraved views cut out from contemporary printed books. The collection, which was previously bound in two large volumes, was subsequently dismounted and the items individually attached to sheets of thick cartridge paper. They are arranged by county in alphabetical order (of the old manner), followed by Orkney and Shetland, and more or less alphabetically within each county. Most of the items depict, whether in whole or in part, medieval churches and other ecclesiastical buildings, but a minority depict castles or other secular dwellings. Most are dated between 1781 and 1792 and between 1811 and 1820, with a few of earlier or later date which Hutton acquired from other sources, and a somewhat larger minority dated 1796, 1801-2, 1805 and 1807. Many, especially the engravings, are undated. For Hutton’s notebooks and sketchbooks, see Adv.MSS.30.5.1-21, 24-26 and 28. For his correspondence and associated papers, see Adv.MSS.29.4.2(i)-(xiii). -

The Gothic Revival Character of Ecclesiastical Stained Glass in Britain

Folia Historiae Artium Seria Nowa, t. 17: 2019 / PL ISSN 0071-6723 MARTIN CRAMPIN University of Wales THE GOTHIC REVIVAL CHARACTER OF ECCLESIASTICAL STAINED GLASS IN BRITAIN At the outset of the nineteenth century, commissions for (1637), which has caused some confusion over the subject new pictorial windows for cathedrals, churches and sec- of the window [Fig. 1].3 ular settings in Britain were few and were usually char- The scene at Shrewsbury is painted on rectangular acterised by the practice of painting on glass in enamels. sheets of glass, although the large window is arched and Skilful use of the technique made it possible to achieve an its framework is subdivided into lancets. The shape of the effect that was similar to oil painting, and had dispensed window demonstrates the influence of the Gothic Revival with the need for leading coloured glass together in the for the design of the new Church of St Alkmund, which medieval manner. In the eighteenth century, exponents was a Georgian building of 1793–1795 built to replace the of the technique included William Price, William Peckitt, medieval church that had been pulled down. The Gothic Thomas Jervais and Francis Eginton, and although the ex- Revival was well underway in Britain by the second half quisite painterly qualities of the best of their windows are of the eighteenth century, particularly among aristocratic sometimes exceptional, their reputation was tarnished for patrons who built and re-fashioned their country homes many years following the rejection of the style in Britain with Gothic features, complete with furniture and stained during the mid-nineteenth century.1 glass inspired by the Middle Ages. -

The SCOTTISH Sale Wednesday 15 and Thursday 16 April 2015 Edinburgh

THE SCOTTISH SALE Wednesday 15 and Thursday 16 April 2015 Edinburgh THE SCOTTISH SALE PICTURES Wednesday 15 April 2015 at 14.00 ANTIQUES AND INTERIORS Thursday 16 April 2015 at 11.00 22 Queen Street, Edinburgh BONHAMS Enquiries Gordon Mcfarlan Sale Number 22 Queen Street Pictures +44 (0) 141 223 8866 22762 Edinburgh EH2 1JX Chris Brickley [email protected] +44 (0) 131 225 2266 +44 (0) 131 240 2297 Catalogue +44 (0) 131 220 2547 fax [email protected] Fiona Hamilton £10 www.bonhams.com/edinburgh +44 (0) 131 240 2631 customer services Iain Byatt-Smith [email protected] Monday to Friday 8.30 to 18.00 VIEWING +44 (0) 131 240 0913 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Friday 10 April 10.00-16.00 [email protected] Arms & Armour Saturday 11 April 13.00-16.00 Kenneth Naples Please see back of catalogue Sunday 12 April 13.00-16.00 Areti Chavale +44 (0) 131 240 0912 for important notice to Monday 13 April 10.00-16.00 +44 (0) 131 240 2292 [email protected] bidders Tuesday 14 April 10.00-16.00 [email protected] Wednesday 15 April 10.00-14.00 Ceramics & Glass Thursday 16 April 09.00-11.00 Rebecca Bohle Illustrations Saskia Robertson Front cover: Lot 54 +44 (0) 131 240 2632 +44 (0) 131 240 0911 Bids Back cover: Lot 52 [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Inside front cover: Lot 449 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Inside back cover: Lot 447 London Books, Maps & Manuscripts To bid via the internet please Facing page: Lot 9 Chris Dawson Henry Baggott visit bonhams.com +44 (0) 131 240 0916 +44 (0) 20 7468 8296 IMPORTANT INFORMATION [email protected] Telephone Bidding [email protected] The United States Government has banned the Bidding by telephone will only be Georgia Williams Jewellery import of ivory into the USA. -

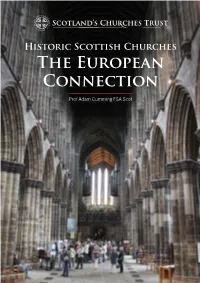

The European Connection

Historic Scottish Churches The European Connection Prof Adam Cumming FSA Scot Adam Cumming Talk “It is often assumed that Scotland took its architectural lead from England, but this is not completely true, Scotland had its own links across Europe, and these developed and changed with time.” cotland has many medieval Glasgow Cathedral which can be churches though not all are shown to have architectural links well known. They deserve across Europe. Sgreater awareness. Many The early Scottish church, that of are ruined but many are not, and Ninian and Columba (as well as many others often survive in some form in others), was part of the early church adapted buildings. before the great schism 1054. It was It is often assumed that Scotland organised a little like the Orthodox took its architectural lead from Churches now. The church below is England, but this is not completely that of Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, an true, Scotland had its own links Orthodox community and similar in across Europe, and these developed plan to early Scottish ones with the and changed with time. The changes church in the centre of the complex. were usually a response to politics It is often described as Celtic and trade. This is of course reflected which is a later description but does in the buildings across Scotland. emphasise a common base with It can be argued that these form a Ireland and Wales etc. There was distinctive part of European culture a great deal of movement across with regional variations. Right is northern Europe and it retained close links with Ireland and elsewhere via ‘Schottenkloster’ and other mission centres. -

Stirling and Forth Valley 3 Day Itinerary

Stirling and Forth Valley Itinerary - 3 Days 01. Callendar House The Battle of Bannockburn Your clients can enjoy a taste of history with a free visit at Cared for by the National Trust for Scotland, the Battle of Callendar House on the outskirts of Falkirk. In the restored 1825 Bannockburn experience will put your clients at the heart of the Kitchen, costumed interpreters create an interactive experience action with cutting-edge 3D technology. They will take command with samples of early-19th century food providing added taste to of their own virtual battlefield to try and re-create the battle. Your stories of working life in a large household. Your clients can also clients can wander across the parkland and admire the restored experience an elegant afternoon tea in the Drawing Room, where commemorative monuments, including the iconic statue of Robert they will tuck into a sumptuous selection of sweet and savoury the Bruce and a meal in the award-wining café. treats with a stunning selection of teas. Glasgow Road Callendar Park Whins of Milton Falkirk, FK1 1YR Stirling, FK7 0LJ www.falkirkcommunitytrust.org www.nts.org.uk Link to Trade Website Link to Trade Website Distance between Callendar House and the Falkirk Wheel is Distance between The Battle of Bannockburn and Stirling Castle is 3.4 miles/5.5km 2.6 miles/4.2km Stirling Castle Stirling Castle is one of Scotland’s grandest castles due to its imposing position and impressive architecture with its superb sculptures. It was a favoured residence of the Stewart kings and queens who held grand celebrations from christenings to coronations. -

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar Introduction The Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland from August 14-26, 2014, was organized for Clan Dunbar members with the primary objective to visit sites associated with the Dunbar family history in Scotland. This Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland focused on Dunbar family history at sites in southeast Scotland around Dunbar town and Dunbar Castle, and in the northern highlands and Moray. Lyle Dunbar, a Clan Dunbar member from San Diego, CA, participated in both the 2014 tour, as well as a previous Clan Dunbar 2009 Tour of Scotland, which focused on the Dunbar family history in the southern border regions of Scotland, the northern border regions of England, the Isle of Mann, and the areas in southeast Scotland around the town of Dunbar and Dunbar Castle. The research from the 2009 trip was included in Lyle Dunbar’s book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part I-The Earls of Dunbar, recently published in May, 2014. Part I documented the early Dunbar family history associated with the Earls of Dunbar from the founding of the earldom in 1072, through the forfeiture of the earldom forced by King James I of Scotland in 1435. Lyle Dunbar is in the process of completing a second installment of the book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part II- After the Fall, which will document the history of the Dunbar family in Scotland after the fall of the earldom of Dunbar in 1435, through the mid-1700s, when many Scots, including his ancestors, left Scotland for America. -

JOHN FOSTER DULLES PAPERS PERSONNEL SERIES The

JOHN FOSTER DULLES PAPERS PERSONNEL SERIES The Personnel Series, consisting of approximately 17,900 pages, is comprised of three subseries, an alphabetically arranged Chiefs of Mission Subseries, an alphabetically arranged Special Liaison Staff Subseries and a Chronological Subseries. The entire series focuses on appointments and evaluations of ambassadors and other foreign service personnel and consideration of political appointees for various posts. The series is an important source of information on the staffing of foreign service posts with African- Americans, Jews, women, and individuals representing various political constituencies. Frank assessments of the performances of many chiefs of mission are found here, especially in the Chiefs of Mission Subseries and much of the series reflects input sought and obtained by Secretary Dulles from his staff concerning the political suitability of ambassadors currently serving as well as numerous potential appointees. While the emphasis is on personalities and politics, information on U.S. relations with various foreign countries can be found in this series. The Chiefs of Mission Subseries totals approximately 1,800 pages and contains candid assessments of U.S. ambassadors to certain countries, lists of chiefs of missions and indications of which ones were to be changed, biographical data, materials re controversial individuals such as John Paton Davies, Julius Holmes, Wolf Ladejinsky, Jesse Locker, William D. Pawley, and others, memoranda regarding Leonard Hall and political patronage, procedures for selecting career and political candidates for positions, discussions of “most urgent problems” for ambassadorships in certain countries, consideration of African-American appointees, comments on certain individuals’ connections to Truman Administration, and lists of personnel in Secretary of State’s office. -

Download Download

THE MONUMENTAL EFFIGIES OF SCOTLAND. 329 VI. THE MONUMENTAL EFFIGIES OF SCOTLAND, FROM THE THIRTEENTH TO THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY. BY ROBERT BRYDALL, F.S.A. SOOT. The custom of carving monumental effigies in full relief does not seem to have come into vogue in Scotland till the thirteenth century—this being also the case in England. From the beginning of that period the art of the sculptor had made great progress both in Britain and on the Continent. At the close of the twelfth century, artists were beginning to depart from the servile imitation of the work of earlier carvers, to think more for themselves, and to direct their attention to nature ; more ease began to appear in rendering the human figure; form was more gracefully expressed, and drapery was treated with much greater freedom. When the fourteenth century drew towards its end, design in sculpture began to lose something of the purity of its style, more attention being given to detail than to general effect; and at the dawn of the sixteenth century, the sculptor, in Scotland, began to degenerate into a mere carver. The incised slab was the earliest form of the sculptured effigy, a treat- ment of the figure in flat relief intervening. The incised slabs, as well as those in flat relief, which were usually formed as coffin-lids, did not, however, entirely disappear on the introduction of the figure in full relief, examples of both being at Dundrennan Abbey and Aberdalgie, as well as elsewhere. An interesting example of the incised slab was discovered at Creich in Fife in 1839, while digging a grave in the old church; on this slab two figures under tabernacle-work are incised, with two shields bearing the Barclay and Douglas arms : hollows have been sunk for the faces and hands, which were probably of a different material; and the well cut inscription identifies the figures as those of David Barclay, who died in 1400, and his wife Helena Douglas, who died in 1421. -

Doors Open Days 2016 in Clackmannanshire

Doors Open Days 2016 in Clackmannanshire 24th & 25th September Year of Innovation, Architecture and Design Doors Open Days 2016 In Clackmannanshire Doors Open Days is celebrated in September throughout Scotland as part of the Council of Europe European Heritage Days. People can visit free of charge places of cultural and historic interest which are not normally open to the public. The event aims to encourage everyone to appreciate and help to preserve their built heritage. Doors Open Days is promoted nationally by The Scottish Civic Trust with part sponsorship from Historic Environment Scotland. In this Year of Innovation, Architecture and Design we will be celebrating the many fine and unusual structures in the county. There will be another special heritage event in Clackmannan to coincide with the Doors Open Days weekend. Most of the buildings in the Clackmannanshire Tower Trail are taking part, as is Hilton Farm, where paintings from the fine Mar & Kellie collection can be seen. The wide range of participating properties includes churches and historic kirkyards, Alva Ice House, Alloa Fire Station and the Ochils Mountain Rescue Team Post, Burnfoot Hill Wind Farm, The Alman’s Coach House Theatre, Dollar Museum and Tullibody Heritage Centre. Sauchie and Coalsnaughton Parish Church will be participating for the first time. Doors Open Days 2016 In Clackmannanshire There will be guided tours of the Speirs Centre, where there is an exhibition celebrating the brewing heritage of Clackmannanshire, as well as a ‘sites of the breweries’ walk around Alloa to complement the display. Please note that in some buildings only the ground floor is accessible to people with mobility difficulties. -

Cramond A5 Leaflet#4 Cramond Kirk 04/08/2011 08:48 Page 1

Cramond A5 leaflet#4_Cramond Kirk 04/08/2011 08:48 Page 1 This window is a memorial to those Beneath the Dalmeny Gallery, the Under the Cramond Gallery is the newest centre is made of cast iron, recalling the connected with the parish who died in stained glass window on the left part of the Kirk – the Chapel, created in days of the iron mills along the River World War I – with 12 names added (pictured below) is in memory of the 2003 to provide a flexible space used for Almond. The oldest tombstone, that of after World War II. daughter of Walter Colvin, minister Morning Prayers on a Sunday as well as John Stalker, dates from 1608. The from 1843-77, while the window on the small weddings, funerals and baptisms. modern stones against the South wall right commemorates Dr George C Stott, It also contains the Wyvern digital organ provide a memorial to members of the minister from 1910-43. installed in 1998. community whose remains have been The artist Douglas Strachan gifted the It is worth spending a moment or two in cremated. Beyond that wall is the 17th mosaic below the memorial window. It the Graveyard. The large obelisk in the Century Manse. depicts the legend of Jock Howison who came to the aid of King James V when he was attacked by robbers. In gratitude the King gave him the lands of Braehead, in return for which he was to provide the monarch with a ewer and basin for washing his hands whenever he passed Cramond Brig. -

2005 Edinburgh Conference

AUTUMN CONFERENCE 2005: EDINBURGH (left) Edinburgh Castle, St Margaret’s Chapel, Douglas Strachan; (above) St Giles Cathedral, James Ballantine; (below left) Dunblane Cathedral, Louis Davis detail n the first day of September this year, BSMGP members recalcitrant BSMGP members/stragglers!) – and then Peter Cormack Ogathered for 4 days of talking, walking, looking and the gave one of his lucid and penetrating commentaries on the occasional frolic. These accounts of the events by two participants allegorical language and significance of Strachan's glass. As usual were held over from the last Newsletter in order to be able to print with Peter, this was erudite and accessible and communicated clearly. them in full. (Photos of glass courtesy Iain Galbraith.) The Shrine is guarded by constantly prowling custodians and FROM IAIN GALBRAITH: photography is forbidden. But what a wealth of meaning and what For once the Scottish weather showed a friendly face and smiled depth of human emotion contained in this glass – the roundels with benevolently throughout this conference – gentle early autumn their cameos of war are worth special attention, believe me. (A weather with splendid ambient temperatures. Accommodation was coffee in the prestigious Queen Anne Coffee House, near the Shrine based at Heriot-Watt University's Riccarton Campus in the Lothian was most welcome, and the accompanying banana cake had all the countryside – comfortable, functional and rather impersonal and lightness and elegance of a small brick – Edinburgh, you can surely with catering reminiscent of school meals! do better than this.) The contents of this Conference divided into clear categories – The company scattered for lunch and gathered again in St Giles the Edinburgh studio of James Ballantine; Arts & Crafts windows in Cathedral where three experts dealt with different topics: Sally Rush Scotland; Glasgow Glass of Alfred Webster & Stephen Adam, and a Bambrough, in the nave of the cathedral, placing Ballantine's schema concluding comprehensive tour of Edinburgh Glass.