Ijrr01004.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

檔案編號︰WTSDC 20/220 Pt

Minutes of the 23rd Meeting of the HKSAR Third Term of Wong Tai Sin District Council (Summary Translation) Date: 5 July 2011 (Tuesday) Time: 2:30 p.m. Venue: Conference Room, Wong Tai Sin District Council, 6/F, Lung Cheung Office Block, 138 Lung Cheung Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon Present: Chairman: Mr. LI Tak-hong, MH, JP Vice-chairman: Mr. WONG Kam-chi, MH, JP Wong Tai Sin District Council Members: Mr. CHAN Lee-shing Ms. CHAN Man-ki, Maggie Mr. CHAN On-tai Mr. CHAN Wai-kwan, Andie Mr. CHAN Yim-kwong, Joe Mr. CHOI Luk-sing, MH Mr. CHOW Ching-lam, Tony, MH Mr. CHUI Pak-tai Mr. HO Hon-man Mr. HO Yin-fai Mr. HUI Kam-shing Mr. KAN Chi-ho, BBS, MH Ms. KWOK Sau-ying Mr. LAI Wing-ho, Joe Mr. LAM Man-fai, JP Dr. LAU Chi-wang, James, BBS, JP 20110718-3_DC[M23].doc 1 Mr. LEE Tat-yan, MH Mr. MOK Chung-fai, Rex, MH Mr. MOK Kin-wing Mr. MOK Ying-fan Dr. SHI Lop-tak, Allen, MH, JP Mr. SO Sik-kin Mr. TO Kwan-hang, Andrew Dr. WONG Kam-chiu, MH Mr. WONG Kwok-tung Mr. WONG Kwok-yan Mr. WONG Yat-yuk Mr. YUEN Kwok-keung Absent with Apologies: Mr. WU Chi-wai, MH In attendance: Mr. Wilson FUNG Executive Director, Corporate AA ) Re.: Item Development ) III(i) Ms. Ivy CHAN General Manager, Corporate AA ) Development ) Mr. YIU Tze-leung Community Services Secretary TWGHs ) Re.: Item Mr. TSENG Wei-yen, Director Urbanage International ) III(ii) William Limited, Architects ) Ms. -

Best of Hong Kong, Zhuhai & Macau

6D5N MEAL PLAN BEST OF HONG KONG, 05 BREAKFASTS 01 LUNCH ZHUHAI & MACAU 03 DINNERS 09 TOTAL MEALS HZM06 HONG KONG – ZHUHAI – MACAU 82 China + Hong Kong by Dynasty Travel • Stanley Market – One of the most visited Hong Kong Street Markets. It is a great place to purchase both Western and SHENZHEN Chinese clothing as well as typical Chinese souvenirs. HONG KONG 2 • Victoria Peak Tour with one way tram ride – The highest point on Hong Kong Island, this has been city’s most exclusive ZHUHAI neighbourhood since colonial times back. Experience one of the world’s oldest and most famous funicular railways to the HONG KONG INTERNATIONAL highest point on Hong Kong Island. 2 ZHUHAI AIRPORT • Madame Tussauds – Meet with over 100 incredibly life like HONG KONG ISLAND wax figures from all around the world including Aaron Kwok, MACAU 1 Donnie Yen, Lee Min Ho, Cristiano Ronaldo, Doraemon, Hello Kitty and McDull. • Ladies Street – Popular street that sells various, low-priced START/END products and also other general merchandise. Breakfast – Local Dim Sum | Lunch – Poon Choi | N NIGHT STAY Dinner – Lei Yue Mun Seafood Dinner BY FLIGHT BY COACH DAY 3 BY CRUISE HONG KONG ZHUHAI • Meixi Royal Stone Archways – An archway to commemorate Chen Fang, who is the first Chinese consul general in Honolulu, DAY 1 was born in Meixi Village. SINGAPORE HONG KONG • Gong Bei Underground Shopping Complex – It is a huge Welcome to a unique experience! shopping mall integrated leisure, entertainment with catering. • Assemble at Singapore Changi Airport for our flight to Hong There are lots of stores engaged in clothes and local snacks, Kong. -

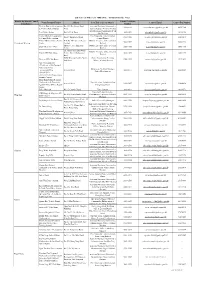

Wong Tai Sin District Celebration Events Calendar

Celebration Events for the 20th Anniversary of the Establishment of the HKSAR Wong Tai Sin District Celebration Events Calendar Date/Time Name of Event Description Venue Organiser(s) Enquiry 14/1/2017 Wong Tai Sin Basketball To enhance the youngsters’ Morse Park Sports Wong Tai Sin District 3143 1142 10:30 – 17:00 Reunification Cup in sense of belonging to the Centre Office; Celebration of the 20th community and to celebrate the Wong Tai Sin Youth Email: Anniversary of the 20th Anniversary of the Development [email protected] Establishment of the Establishment of the HKSAR Network HKSAR with residents from different sectors in Wong Tai Sin district through this basketball tournament 11/2/2017 Commendation To commend the WTS Youth Wong Tai Sin Wong Tai Sin District 3143 1142 14:00 – 17:00 Ceremony for Wong Tai Pioneers with outstanding Temple Court Office; Sin Youth Pioneers cum performance and to celebrate Wong Tai Sin Youth Email: Drama Show in the 20th Anniversary of the Development [email protected] Celebration of the 20th Establishment of the HKSAR by a Network Anniversary of the drama performance Establishment of the HKSAR Celebration Events for the 20th Anniversary of the Establishment of the HKSAR Wong Tai Sin District Celebration Events Calendar Date/Time Name of Event Description Venue Organiser(s) Enquiry 13/2/2017 & Wong Tai Sin Soccer To build up the youngsters’ Lok Fu Recreation Wong Tai Sin District 3143 1142 16/2/2017 Reunification Cup in sense of pride and to celebrate Ground (Artificial Office; 18:30 – 21:30 Celebration -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Product Design Creative Product Design © Sendpoints Publishing Co., Ltd

Product Design Creative Product Design © Sendpoints Publishing Co., Ltd. EDIT & PUBLISH Sendpoints Publishing Co., Ltd. PUBLISHER Lin Gengli PUBLISHING DIRECTOR Lin Shijian PRODUCTION EDITORIAL Sundae Li EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lamps 004 Jack Weng CREATIVE DIRECTOR Lin Shijian EXECUTIVE DESIGNER Shelves & Cabinets 056 Huang Xiaoqiong PROOFREADING Sundae Li Tables & Chairs 124 ADDRESS Room 15A Block 9 Tsui Chuk Garden, Wong Tai Sin, Kitchenware & Containers 214 Kowloon, Hong Kong Tel +852-35832323 Fax +852-35832448 Email [email protected] Tools 314 Website www.sendpoint.com.cn Distributed by Guangzhou Sendpoints Book Co., Ltd. Sales Manager ZhangJuan (China) Limbo (International) Guangzhou Tel +86-20-89095121 Beijing Tel +86-10-84139071 Shanghai Tel +86-21-63523469 Email [email protected] Website www.sendpoint.com.cn Online store shanbents.tmall.com ISBN 978-988-16835-3-3 Printed and bound in China All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. For more information, please contact Sendpoints Publishing Co., Ltd. Booleanos [ Mexico ] DESIGNER Joel Escalona The Boleanos is a Masisa boards shelving unit that can double as a low side table. A stunning piece of work that deals in the abstract, it is made up of a pile of wood blocks that look as though they are going to topple over at any moment. Overlapping in a seemingly impossible way, the furniture piece defies logic in more than a few ways. Comissioned by Glocal Design Magazine and Masisa brand for the opening of the Design Week Mexico 2012, specifically the exhibition ‘Hecho en México’ Boleanos is a stunning design. -

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

Services Provided by Government Departments, Public Bodies, Chambers of Commerce and Supporting Organisations in Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao

Chapter 10 I Channels for seeking assistance Services provided by government departments, public bodies, chambers of commerce and supporting organisations in Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao Hong Kong Channels for enquiries and reporting suspected corruption In Hong Kong, any person may lodge a complaint with or make an enquiry at the ICAC through the following channels. All complaints and enquiries are kept in strict confidence: By phone: (852) 25 266 366 (24-hour hotline) By mail: G.P.O. Box 1000, Hong Kong In person: ICAC Report Centre, 303 Java Road, North Point, Hong Kong (24-hour service) or any ICAC Regional Offices ICAC Regional Office Contact Information Regional Office Address: G/F, Tung Wah Mansion, (Hong Kong East) 201 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Wan Chai, Eastern District Hong Kong Tel: (852) 2519 6555 Regional Office Address: G/F, Harbour Commercial Building, (Hong Kong West/Islands) 124 Connaught Road Central, Central & Western District, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong Southern District, Islands Tel: (852) 2543 0000 Regional Office Address: Shop No. 4, G/F, Kai Tin Building, (Kowloon East/Sai Kung) 67 Kai Tin Road, Lam Tin, Kowloon Kwun Tong, Wong Tai Sin, Tel: (852) 2756 3300 Sai Kung 140 Chapter 10 I Channels for seeking assistance ICAC Regional Office Contact Information Regional Office Address: G/F, Nathan Commercial Building, (Kowloon West) 434-436 Nathan Road, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon City, Yau Tsim Mong, Kowloon Sham Shui Po Tel: (852) 2780 8080 Regional Office Address: G06-G13, G/F, (New Territories East) Shatin Government Offices, Shatin, Tai Po, North District 1 Sheung Wo Che Road, Shatin, New Territories Tel: (852) 2606 1144 Regional Office Address: Shop B1, G/F, Tsuen Kam Centre, (New Territories South West) 300-350 Castle Peak Road, Tsuen Wan, Tsuen Wan, Kwai Tsing New Territories Tel: (852) 2493 7733 Regional Office Address: G/F, Fu Hing Building, (New Territories North West) 230 Castle Peak Road, Yuen Long, Yuen Long, Tuen Mun New Territories Tel: (852) 2459 0459 For the latest information on ICAC services, please visit the ICAC website (www. -

Supplemental Material

Supplementary Material 15-Year PM2.5 Trends in the Pearl River Delta Region and Hong Kong from Satellite Observation C.Q. Lin 1,2, Y. Li 3, A.K.H. Lau 1,2,4,*, C.C. Li 5, J.C.H. Fung 2,4,6 * Corresponding author. Tel: (852) 2358 6944; Fax: (852) 2358 1534 E-mail address: [email protected] This file includes: Pages: 1-9 Figures: S1-S6 Tables: S1-S2 1 List of Table Titles and Figure Captions Table S1. Mean PM2.5 trends for the entire PRD region and different cities during the three FYP th periods. Cities are ordered by PM2.5 concentration trends during the 12 FYP period. Table S2. Mean PM2.5 concentration trends for the districts in Hong Kong during the three FYP th periods. Districts are ordered by PM2.5 concentration trends during the 12 FYP period. Figure S1. The left panel shows the topography and the cities in the PRD region: the capital Guangzhou (GZ), the special economic zones of Shenzhen (SZ) and Zhuhai (ZH), Dongguan (DG), Fushan (FS), Zhongshan (ZS), Zhaoqing (ZQ), Jiangmen (JM), and Huizhou (HZ), and the two special administrative regions of Hong Kong (HK) and Macau (MC). The right panel shows the topography and the 18 districts in Hong Kong: North (NO), Yuen Long (YL), Tai Po (TP), Tuen Mun (TM), Tsuen Wan (TW), Sha Tin (ST), Sai Kung (SK), Kwai Tsing (KI), Sham Shui Po (SS), Yau Tsim Mong (YT), Kowloon City (KC), Wong Tai Sin (WT), Kwun Tong (KU), Central and Western (CW), Wan Chai (WC), Eastern (EA), Southern (SO), and Islands (IS). -

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T. Tsang Tai Uk (曾大屋, literally the Big Mansion of the Tsang Family) is also Historical called Shan Ha Wai (山廈圍, literally, Walled Village at the Foothill). Its Interest construction was started in 1847 and completed in 1867. Measuring 45 metres by 137 metres, it was built by Tsang Koon-man (曾貫萬, 1808-1894), nicknamed Tsang Sam-li (曾三利), who was a Hakka (客家) originated from Wuhua (五華) of Guangdong (廣東) province which was famous for producing masons. He came to Hong Kong from Wuhua working as a quarryman at the age of 16 in Cha Kwo Ling (茶果嶺) and Shaukiwan (筲箕灣). He set up his quarry business in Shaukiwan having his shop called Sam Lee Quarry (三利石行). Due to the large demand for building stone when Hong Kong was developed as a city since it became a ceded territory of Britain in 1841, he made huge profit. He bought land in Sha Tin from the Tsangs and built the village. The completed village accommodated around 100 residential units for his family and descendents. It was a shelter of some 500 refugees during the Second World War and the name of Tsang Tai Uk has since been adopted. The sizable and huge fortified village is a typical Hakka three-hall-four-row Architectural (三堂四横) walled village. It is in a Qing (清) vernacular design having a Merit symmetrical layout with the main entrance, entrance hall, middle hall and main hall at the central axis. Two other entrances are to either side of the front wall. -

List of Research Postgraduate Students (2021-22)

List of Research Postgraduate Students (2021-22) Student Academic Background Research Topic Supervisor(s) Ho Tsz Wai MArch (CUHK) BArch (CUHK) Co-designing for Positive Education in Hong Kong : Architectural Redesign Framework of Physical Environment for Teaching, Learning And Wellbeing David DERNIE, Thomas CHUNG CAI Meng MSc (CUHK), BEng (Wuhan) Developing a high-resolution urban carbon emission inventory for the Greater Bay Area: an open data approach Edward NG KWOK Yu Ting MSc (Imperial College London) Mesoscale urban climate modelling for high-rise, high-density cities: implications on the urban planning of Hong Kong Edward NG LIU Sheng MEng (Hunan Technology), BEng (Dalian) Building performance and passive adaptation strategies in the context of future climate change: A case study of the residential buildings in subtropical Hong Edward NG Kong OUYANG Wanlu MSc, BSc (Wuhan) Improve Microclimate and Pedestrian Thermal Comfort by Optimising Urban Greenery Combinations on Ground Level, Vertical Wall, and Rooftop Locations Edward NG WANG Ran MSc (CUHK), BSc (Nanjing Agriculture) urban expansion patterns and surface urban heat island effect of selected Chinese cities from 2000 to 2005 based on the local climate zone scheme Edward NG Cheung Ka Ming MSc Health, Wellbeing and Sustainable Development of Healthy City Assessment Tool for Active Lifestyle Edward NG Buildings (UCL) MSc Fire and Safety Engineering (HK PolyU) XIANG Luyao MArch (Sichuan UT), BSsc (Zhejiang UT) Outdoor environment as a means to relieve human psychological stress in -

Coe College Bands Concert Tour to Taiwan 2008 (* B= Breakfast, L= Lunch, D= Dinner)

Page 1 Coe College Bands 2008 Concert Tour to Taiwan Updated on July 21, 2008 Created by Friendship Ambassadors Foundation, Inc. Coe College Bands Concert Tour to Taiwan 2008 (* B= breakfast, L= lunch, D= dinner) Day 1 – August 3rd , Sunday: Depart for Taiwan Depart the Chicago O’Hare International Airport with your chosen carrier for your international flight (UA 0109) to Taiwan at 10:00 am. Please arrive early at the airport. Please double check with Friendship Ambassadors Foundation in advance for check-in times and other requirements. You flight lands in Los Angeles at 12:10 pm; your connecting flight CI 0005 departs at 3:55 pm. Try to get some rest on board. To minimize the effects of jet lag, we advise to avoid sugars, caffeine, salts, and alcohol. Drink a lot of water to keep hydrated. Day 2 – August 4th , Monday: Arrive in Taiwan (All meals en route) Arrive Chiang Kai Shek International Airport in Taoyuan, Taiwan at 8:10 pm local time. Claim your luggage and board your private motor coach. Meet your local English speaking FAF Tour Manager and head to the Chientan Youth Activity Center – your accommodations for your stay in Taipei. Have a refreshing and relaxing night after your long flight and recover from your jet lag! Welcome to Taiwan! Taiwan has a rich, colorful history. It became a protectorate of the Chinese Empire in 1206, the year the great Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan founded the Yuan dynasty. The island was made a prefecture (county) of the coastal mainland province of Fukien in 1684, and in 1885, during the Ching or Manchu dynasty (China's last reigning house), Taiwan was proclaimed a separate province of China. -

Hong Kong Bird Report

Hong Kong Bird Report 香港鳥類報告 2009-10 Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM 防雨水設計 8x42 EXWP I / 10x42 EXWP I • 8倍放大率 / 10倍放大率 • 防水設計, 尤合戶外及水上活動使用 • 密封式內充氮氣, 有效令鏡片防霞防霧 • 高折射指數稜鏡及多層鍍膜鏡片, 確保影像清晰明亮 • 能阻隔紫外線, 保護視力 港澳區代理:大通拓展有限公司 荃灣沙咀道381-389號榮亞工業大廈一樓C座 電話:(852) 2730 5663 傳真:(852) 2735 7593 電郵:[email protected] 野外觀鳥活動 必備手冊 www.wanlibk.com www.hkbws.org.hk bird.indd 1 05/11/2010 11:57 AM Published in August 2012 2012年8月出版 The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 14/F., Ruby Commercial Building, 480 Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China 中國香港九龍彌敦道480號鴻寶商業大廈14樓 (Approved Charitable Institution of Public Character) (認可公共性質慈善機構) Editors: John A. Allcock, Geoff J. Carey, Gary Chow and Geoff Welch 編輯:柯祖毅、賈知行、周家禮、Geoff Welch Front Cover 封面: Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 鵪鶉 Long Valley, 24th October 2009 塱原 2009年10月24日 Peter and Michelle Wong 黃理沛 江敏兒 Hong Kong Bird Report 2009-10: Committees The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 Committees and Officers 2012 榮譽會長 Honorary President 林超英先生 Mr. Lam Chiu Ying 執行委員會 Executive Committee 主席 Chairman 劉偉民先生 Mr. Lau Wai Man, Apache 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳祖南博士 Dr. Ng Cho Nam 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳 敏先生 Mr. Michael Kilburn 義務秘書 Hon. Secretary 陳慶麟先生 Mr. Chan Hing Lun, Alan 義務司庫 Hon. Treasurer 周智良小姐 Ms. Chow Chee Leung, Ada 委員 Committee members 林超英先生 Mr. Lam Chiu Ying 李慧珠小姐 Ms. Lee Wai Chu, Ronley 柯祖毅先生 Mr. John Allcock 方健華先生 Mr. Fong Kin Wa, Forrest 區俊茵小姐 Ms. Au Chun Yan, Joanne 施百納先生 Mr. Bena Smith 蘇毅雄先生 Mr.