Jay's Treaty: the Transformation of Lake Champlain Commerce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dams and Reservoirs in the Lake Champlain Richelieu River Basin

JUST THE FACTS SERIES June 2019 DAMS AND RESERVOIRS IN THE LAKE CHAMPLAIN RICHELIEU RIVER BASIN MYTH Water released from tributary dams in the United States causes flooding in Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River. FACT Water levels in Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River Generally, mass releases of water from flood control are primarily affected by precipitation from rain or dams are avoided. In addition to compromising the snowmelt. structural integrity of the dams, mass releases would also endanger the very communities that these dams are built Because of its size, Lake Champlain can store a lot of to protect. water; the flood control dams and reservoirs in the basin, which are very small in comparison to the lake, do not When conditions force the release of more water than significantly change water levels of the lake and river as hydropower plants can handle, the increase in water they release water. levels immediately below the dam will be much greater than the increase on Lake Champlain. This is true even during high water and flooding events. Consider, for instance, when Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River experienced extreme flooding between April and June 2011, the additional releases flowing from Waterbury Reservoir—the largest flood control reservoir in the Vermont portion of the basin, contributed less than 2 centimetres (¾ inch) to the elevation of Lake Champlain and the upper Richelieu River. International Lake Champlain-Richelieu River Study Board FACT FACT Dams in the US portion of the basin are built for one of Waterbury Reservoir in Vermont is the largest reservoir two purposes: flood control or hydroelectric power. -

The Mapping of Samuel De Champlain, 1603–1635 Conrad E

51 • The Mapping of Samuel de Champlain, 1603–1635 Conrad E. Heidenreich The cartography of Samuel de Champlain marks the be- roster of 1595 he was listed as a fourier (sergeant) and aide ginning of the detailed mapping of the Atlantic coast north to the maréchal de logis (quartermaster), apparently of Nantucket Sound, into the St. Lawrence River valley, reaching the rank of maréchal himself.4 The same pay ros- and, in a more cursory fashion, to the eastern Great Lakes. ter states that in 1595 he went on a secret mission for the Previous maps were based on rapid ship-board reconnais- king that was regarded to be of some importance. He also sance surveys made in the early to middle sixteenth cen- made a “special report” to Henri IV after his West Indian tury, particularly on the expeditions of Jacques Cartier and voyage (1601) and after the first two voyages to Canada Jean-François de La Rocque, sieur de Roberval (1534 – (1603 and 1607). These reports seem to indicate that 43). These maps conveyed little more than the presence of Champlain had a personal relationship with Henri IV, a stylized coastline. The immediate result of the Cartier- probably accounting for the pension the king awarded him Roberval expeditions was that France lost interest in sometime before 1603.5 After the war, Champlain joined North America, except for fishing off the northeast coast. his uncle’s ship, the 500-tun Saint-Julien, in Spanish The indigenous population was considered impoverished Caribbean service.6 In June 1601, Champlain was in and hostile, there were no quick riches, and the winters Cádiz where he was a witness to his dying uncle’s testa- were so brutal that the French wondered whether Euro- ment leaving him a large estate near La Rochelle as well as peans could live there. -

Annex VIII Casestudy0304 Ch

IEA Hydropower Implementing Agreement Annex VIII Hydropower Good Practices: Environmental Mitigation Measures and Benefits Case study 03-04: Fish Migration and River Navigation - Chambly Dam, Canada Key Issues: 3- Fish Migration and River Navigation Climate Zone: Cf: Temperate Subjects: - Fishway Effects: - Allow upstream migration of juvenile American eel ( Anguilla rostrata ) Project Name: Chambly Dam Country: Canada Implementing Party & Period - Project: Hydro-Québec 1965 - Good Practice: Hydro-Québec 1997 Key Words: American eel, ladder, fish migration, Chambly Dam Abstract: For 150 years, the Richelieu River (Québec, Canada) supported a sizable commercial silver American eel fishery. A sharp and constant decline of annual landings since 1981 has been at least partly related to the rebuilding, in 1965, of an old cribwork. In 1997, a ladder was retrofitted on the 270-m Chambly Dam to allow eel migration and enhance recruitment. 1. Outline of the Project Chambly Dam is located on the Richelieu River, a tributary of the St. Lawrence near Montréal (Québec, Canada). It is a 270-m-long concrete overflow weir and the water head is approximately 5 m. It was built in 1965 to replace an old cribwork dam that was constructed in 1896. 2. Features of the Project Area The Richelieu River drains Lake Champlain, a large lake bordering New York and Vermont states (USA) and extending into Québec. Lake Champlain is connected to the Hudson River and to the Great Lakes by a network of locks and canals. The Richelieu River extends for 115 km between Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River. Figure 1 Location Map of the project From June to September, the average discharge is 271 m3/s (1937-1996) or about 3.5% of the St. -

17 Major Drainage Basins

HUC 8 HYDROLOGIC UNIT NAME CLINTON 04120101 Chautauqua-Conneaut FRANKLIN 04150409 CHAMPLAIN MASSENA FORT COVINGTON MOOERS ST LAWRENCE CLINTON 04120102 Cattaraugus BOMBAY WESTVILLE CONSTABLE CHATEAUGAY NYS Counties & BURKE LOUISVILLE 04120103 Buffalo-Eighteenmile BRASHER 04150308 CHAZY ALTONA ELLENBURG BANGOR WADDINGTON NORFOLK MOIRA 04120104 Niagara ESSEX MALONE DEC Regions JEFFERSON 6 04150307 BEEKMANTOWN MADRID 05010001 Upper Allegheny LAWRENCE BELLMONT STOCKHOLM DANNEMORA BRANDON DICKINSON PLATTSBURGH LEWIS OGDENSBURG CITY LISBON 05010002 Conewango 5 PLATTSBURGH CITY HAMILTON POTSDAM SCHUYLER FALLS SARANAC 05010004 French WARREN OSWEGATCHIE DUANE OSWEGO 04150306 PERU 04130001 Oak Orchard-Twelvemile CANTON PARISHVILLE ORLEANS WASHINGTON NIAGARA DE PEYSTER ONEIDA MORRISTOWN HOPKINTON WAVERLY PIERREPONT FRANKLIN 04140101 Irondequoit-Ninemile AUSABLE MONROE WAYNE BLACK BROOK FULTON SARATOGA DEKALB HERKIMER BRIGHTON GENESEE SANTA CLARA CHESTERFIELD 04140102 Salmon-Sandy ONONDAGA NYS Major 04150406 MACOMB 04150304 HAMMOND ONTARIO MADISON MONTGOMERY RUSSELL 04150102 Chaumont-Perch ERIE SENECA CAYUGA SCHENECTADY HERMON WILLSBORO ST ARMAND WILMINGTON JAY WYOMING GOUVERNEUR RENSSELAER ALEXANDRIA CLARE LIVINGSTON YATES 04130002 Upper Genesee OTSEGO ROSSIE COLTON CORTLAND ALBANY ORLEANS 04150301 04150404 SCHOHARIE ALEXANDRIA LEWIS 7 EDWARDS 04150408 CHENANGO FOWLER ESSEX 04130003 Lower Genesee 8 TOMPKINS CLAYTON SCHUYLER 9 4 THERESA 04150302 TUPPER LAKE HARRIETSTOWN NORTH ELBA CHAUTAUQUA CATTARAUGUS PIERCEFIELD 02050104 Tioga ALLEGANY STEUBEN -

Surface Waters of Vermont

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 424 SURFACE WATERS OF VERMONT BY C. H. PIERCE Prepared in cooperation with the STATE OF VERMONT WASHINGTON GOVEENMENT PBINTING OFFICE 1917 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BK PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 25 CENTS PER COPY CONTENTS. Introduction.............................................................. 5 Cooperation................................................................ 8 Division of work.......................................................... 8 Definition of terms......................................................... 9 Explanation of data........................................................ 9 Accuracy of field data and computed results................................ 11 Gaging stations maintained in Vermont..................................... 12 St. Lawrence River basin................................................. 13 Lake Champlain drainage basin......................................... 13 General features................................................... 13 Gaging-station records.............................................. 14 Lake Champlain at Burlington, Vt.............................. 14 Lake Champlain outlet (Richelieu River) at Chambly, Province of Quebec.1................................................. 20 Poultney Eiver near Fair Haven, Vt............................ 25 Otter Creek at Middlebury, -

Montréal-Est 40 15 Saint-Hyacinthe 640 138 440 25 223 Sainte-Julie 20 344 229 40 Boucherville Beloeil

Western New England Greenway Upper Housatonic Valley National Heritage Area & Champlain Valley National Heritage Partnership Long Island Sound to Montreal Quebec - Route Map 6 of 6: North Hero, Vermont to Montreal, Quebec National Park Service/U.S. Department of the Interior rom North Hero, VT to Montreal it is flat so it is F the wind to be aware of not the hills. A short 10 mile loop around Isle La Motte will take you past Quebec City quarries with the oldest known fossils in the world and the site of Samuel de Champlain’s landing in QUEBEC 40 173 Vermont. Have your passport ready when you get to 20 the border follow the directions to meet Route Verte Montreal 55 in Lacoile, QC. Halfway to St. Jean sur Richelieu are 201 10 Sherbrooke signs Route de Forts which will lead you Ft. Lennox. 15 St. Jean sur Richelieu A short boat ride to the island fort is both fun and 89 ME educational. In St. Jean sur Richelieu the bike path 91 Burlington along the Chambly Canal starts at Pont Gouin and Augusta Montpelier 95 ends near Ft. Chambly. 87 VT 93 Portland Chambly to Montreal becomes more urban the farther 89 NH you go but it is all on bike paths or bike lanes. Once NY Concord you enter the Montreal area you are in a complex with Manchester hundreds of miles of bike paths and lanes and unless Albany 91 93 90 it’s race time you can ride the Formula One track. MA 90 Boston Springeld Providence Hartford RI 87 CT 95 84 New York City Western New England Greenway Section 6: North Hero, Vermont to Montreal, Quebec Cue Sheet VT 211.7 NORTH HERO - Continue on Rt. -

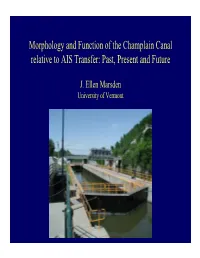

Morphology and Function of the Champlain Canal Relative to AIS Transfer: Past, Present and Future

Morphology and Function of the Champlain Canal relative to AIS Transfer: Past, Present and Future J. Ellen Marsden University of Vermont St. Lawrence R. Richelieu River Chambly Canal Lake Champlain Champlain Erie Canal Canal Mohawk River Hudson River St. Lawrence R. Richelieu River Chambly Canal Lake Champlain Mohawk River Hudson River St. Lawrence R. Richelieu River Lake Champlain Champlain Canal Mohawk River Hudson River Champlain Canal Glens Falls Feeder Canal 7 89 11 5 6 12 Whitehall 4 Fort 3 Fort 2 Ann Lake Champlain Waterford 1 Edward Hudson River Vectors of exotic species introduced into Lake Champlain N = 48 species (+1) (Marsden and Hauser 2009 Exotic species in Lake Champlain. JGLR 35:25-265) illegal stocked unintentional & bait Champlain Canal – 40% of AIS Chambly canalscanals unknown 0 5 10 15 20 Number of Species Introductions via the Champlain Canal Purple loosestrife Bythinia Water chestnut Woodland pondsnail Yellow floating heart? Banded mystery snail Flowering rush? Buffalo pebble snail European frog’s bit? Sharp hornsnail Slender-leafed naiad? Piedmont snail Zebra mussel Carp Asian clam (en route) Blue-back herring Gizzard shad Water flea (Eubosmina) Brook silverside Spiny water flea (Bythotrephes) White perch (en route) Largemouth bass Lake Champlain as an exotic From St. Lawrence to Hudson species conduit… silver lamprey St. Lawrence R. longnose gar bowfin Richelieu River brook stickleback Chambly rock bass Canal logperch Lake liver elimia Champlain Champlain Canal Mohawk River Hudson River from Daniels 2001 Lake Champlain as an exotic From St. Lawrence to Hudson species conduit… silver lamprey St. Lawrence R. longnose gar bowfin Richelieu River brook stickleback Chambly rock bass Canal logperch Lake liver elimia Champlain From Hudson to St. -

493 St. Lawrence River Basin 04295000 Richelieu River

ST. LAWRENCE RIVER BASIN 493 04295000 RICHELIEU RIVER (LAKE CHAMPLAIN) AT ROUSES POINT, NY LOCATION.--Lat 44°59'46", long 73°21'37", Clinton County, Hydrologic Unit 02010006, on left bank at outlet of Lake Champlain in Rouses Point, and 1.0 mi south of Fort Montgomery ruins. DRAINAGE AREA.--8,277 mi2. PERIOD OF RECORD.--October 1863 to December 1870 (maximum and minimum monthly gage heights at St. Johns, Quebec, published in WSP 97) and March 1871 to current year (daily gage heights prior to October 1970, elevations thereafter: those for 1871-1907 published in WSP 894). Gage heights prior to October 1, 1925, published as "Richelieu River at Fort Montgomery, Rouses Point". Discharge records for January 1875 to September 1916 at "Chambly, Quebec," published in WSP 65, 82, 97, 129, 170, 206, 424, and 1307 have been found to be unreliable and should not be used. Daily discharge record for "Richelieu River at Fryers Rapids, Quebec," published in Water Survey of Canada annual reports. GAGE.--Water-stage recorder. Datum of gage is NGVD of 1929. March 1871 to May 1923, nonrecording gage located in Fort Montgomery and May 1923 to October 1938, nonrecording gage at present site. Prior to October 1970, at datum 93.00 ft higher. REMARKS.--Area of lake surface about 490 mi2. Total volume below 92.5 ft elevation, reported by Lake Champlain Studies Center, 902.2 bil ft3. Telephone gage-height telemeter at station. EXTREMES FOR PERIOD OF RECORD.--Maximum elevation observed, 101.88 ft, Apr. 25, 1993; minimum observed, 92.17 ft, Oct. -

Water Quality of the Richelieu and Yamaska Rivers, 3

WATER BIOLOGICAL SEDIMENTS SHORELINES RESOURCES USES Water quality of the Richelieu of the St. Lawrence River. Its mean annual flow was 323 m3/s during the 2001–2003 period, and 484 m3/s during the 2004–2013 period and Yamaska rivers at the municipality of Sorel-Tracy. From its source in Lake Champlain in the United States, the river flows northward into the St. Lawrence Toxic contamination River at Sorel-Tracy. Its main tributaries in Quebec are the South, Huron, Lacolle and Acadia rivers. The Canadian part of the basin Issue measures 3855 km2, which represents 16% of its total area. The watersheds of the Richelieu and Yamaska rivers are located in the Centre du Québec region, where there are numerous socio- The Yamaska River starts in Brome Lake and empties into economic activities. With a drainage basin area of 23 720 km2, the the St. Lawrence River in the Lake Saint-Pierre area. Its watershed Richelieu River is the most significant tributary on the south shore covers a total area of 4784 km2 and is drained by three main tributaries: Black, Yamaska North and Yamaska South East rivers. Figure 1 Drainage basins of the Richelieu The river’s runoff volume is six times smaller than that of the and Yamaska rivers Richelieu River. For the 2001–2003 and 2004–2013 periods, its estimated runoff volume was 46 m3/s and 70 m3/s at Saint-Hyacinthe. The watershed regions of the Richelieu and Yamaska rivers are home to a number of industries specialized in agri-food, chemicals, metals processing, plastics and textiles. -

Assessing the Reliability of the 1760 British Geographical Survey of the St

Assessing the Reliability of the 1760 British Geographical Survey of the St. Lawrence River Valley by Nicholas Gliserman A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the USC Graduate School University of Southern California In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Geographic Information Science and Technology) May 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Nicholas Gliserman ii To my loving wife, Christina Copland iii Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. vi List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... x Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ xi List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... xii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ xiii Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Towards a Historiographical Synthesis of Archival and Digital Methods .................... 7 2.1. The Underwhelming Presence of Historical Maps in the Spatial Humanities ................... 8 2.2. Scholarship on the Murray -

The Lachine Canal, Montreal, Quebec Pauline Desjardins

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 28 Article 5 1999 From the Warehouses to the Canal By Rail ca. 1830: The Lachine Canal, Montreal, Quebec Pauline Desjardins Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Desjardins, Pauline (1999) "From the Warehouses to the Canal By Rail ca. 1830: The Lachine Canal, Montreal, Quebec," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 28 28, Article 5. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol28/iss1/5 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol28/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. From the Warehouses to the Canal By Rail ca. 1830: The Lachine Canal, Montreal, Quebec Cover Page Footnote This paper is a part of my dissertation concerning the impact of the Lachine Canal on Montrealers during the 19th century. I would like to thank the old Port of Montreal Corporation for their authorization to use all the date we recovered during the five-year archaeolgocial project, as part of the redevelopment of the old section of the port of Montreal including the lower entrance of the Lachine Canal. My Ph.D. research was made possible with a grant from the Fonds pour la Formation de Chercheurs et l'Aide a la Recherche (FCAR). I would also thank the members of CNEHA conference for their support, and particularly Karen Bescherer Metheny for her splendid encouragement and the reviewers for their pertinent comments. -

1609: Samuel De Champlain Reaches the Lake

1609: Samuel de Champlain Reaches the Lake Champlain’s Battle Scene 1609.Samuel de Champlain ca. 1613. 1609: Quadricentennial Curriculum Samuel de Champlain Reaches the Lake: 1 Background Samuel de Champlain By Joseph-André Senécal Samuel de Champlain was born at Brouage around 1570. There is no known portrait of the Father of New France and little is known about his family. His father and uncle were sea captains and he informed the French court that the art of navigation had attracted him from his “tender youth.” We do not know where he learned the many skills (navigation; cartography; drawing; geography) that prepared him for his North American experience. In all likelihood Champlain learned about sailing at Brouage, a port on the French Atlantic coast, a key stopover for ships of all nations who needed to take on cargoes of salt before sailing for the fishing grounds off Newfoundland and the coast of New England. Concerning his military skills, we know that he served as a soldier in the French province of Brittany where Catholic forces allied with Spain opposed Henry IV as the rightful king of France. From 1595 to 1598, he served in the army of Henry IV with the title of sergeant quartermaster. His uncle was also involved in this final chapter of the war of religions and, at the conclusion of hostilities, we find them reunited at the port of Blavet where the two sailed for Spain in 1598. From Spain Champlain joined a fleet bound for the Spanish West Indies, a voyage that took him two years and a half.