American Viticultural Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

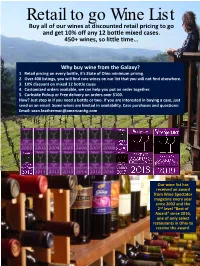

Retail to Go Wine List Buy All of Our Wines at Discounted Retail Pricing to Go and Get 10% Off Any 12 Bottle Mixed Cases

Retail to go Wine List Buy all of our wines at discounted retail pricing to go and get 10% off any 12 bottle mixed cases. 450+ wines, so little time… Why buy wine from the Galaxy? 1. Retail pricing on every bottle, it's State of Ohio minimum pricing. 2. Over 400 listings, you will find rare wines on our list that you will not find elsewhere. 3. 10% discount on mixed 12 bottle cases 4. Customized orders available, we can help you put an order together. 5. Curbside Pickup or Free delivery on orders over $100. How? Just stop in if you need a bottle or two. If you are interested in buying a case, just send us an email. Some wines are limited in availability. Case purchases and questions: Email: [email protected] Our wine list has received an award from Wine Spectator magazine every year since 2002 and the 2nd level “Best of Award” since 2016, one of only select restaurants in Ohio to receive the award. White Chardonnay 76 Galaxy Chardonnay $12 California 87 Toasted Head Chardonnay $14 2017 California 269 Debonne Reserve Chardonnay $15 2017 Grand River Valley, Ohio 279 Kendall Jackson Vintner's Reserve Chardonnay $15 2018 California 126 Alexander Valley Vineyards Chardonnay $15 2018 Alexander Valley AVA,California 246 Diora Chardonnay $15 2018 Central Coast, Monterey AVA, California 88 Wente Morning Fog Chardonnay $16 2017 Livermore Valley AVA, California 256 Domain Naturalist Chardonnay $16 2016 Margaret River, Australia 242 La Crema Chardonnay $20 2018 Sonoma Coast AVA, California (WS89 - Best from 2020-2024) 241 Lioco Sonoma -

J. Wilkes Wines Central Coast

Gold Wine Club Vol 28i12 P TheMedal WinningWine Wines from California’s Best Family-Ownedress Wineries. J. Wilkes Wines Central Coast Gold Medal Wine Club The Best Wine Club on the Planet. Period. J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red” Blend Paso Robles Highlands District, California 1,000 Cases Produced The J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red” is a blend of 90% Barbera and 10% Lagrein from the renowned Paso Robles Highlands District on California’s Central Coast. This District, which is the most southeast sub appellation within the Paso Robles AVA, is an absolutely fantastic place to grow wine grapes, partly due to its average 55 degree temperature swing from day to night (the highest diurnal temperature swing in the United States!), and also in part to its combination of sandy and clay soils that promote very vigorous vines. The high temperature swing, by the way, crafting bold, complex red blends like the J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red.” This wine opens with incredibly seductive slows the ripening rate of the fruit on the vine and allows flavors to develop, which is especially important when and just the right balance of bright, deep, and elegant nuances. Suggested food pairings for the J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’saromas Red”of blackberry, include barbecued huckleberry, steak, and pork, freshly or beefberry stew. pie. AgedThe palate in oak. is Enjoy dry, but now very until fruity 2027. with dark berry flavors Gold Medal Special Selection J. Wilkes 2016 Chardonnay Paso Robles Highlands District, California 1,000 Cases Produced J. Wilkes’ 2016 Chardonnay also comes from the esteemed Paso Robles Highlands District, a region that may be dominated by red wine grapes, but the Chardonnay grown here is well-respected and offers some 2016 Chardonnay opens with dominating aromas of ripe pear, green apple and lime zest. -

Lamorinda AVA Petition

PETITION TO ESTABLISH A NEW AMERICAN VITICULTURAL AREA TO BE NAMED LAMORINDA The following petition serves as a formal request for the establishment and recognition of an American Viticultural Area to be named Lamorinda, located in Contra Costa County, California. The proposed AVA covers 29,369 acres and includes nearly 139 acres of planted vines and planned plantings. Approximately 85% of this acreage is occupied or will be occupied by commercial viticulture (46 growers). There are six bonded wineries in the proposed AVA and three additional growers are planning bonded wineries. The large number of growers and relatively limited acreage demonstrates an area characterized by small vineyards, a result of some of the unique characteristics of the area. This petition is being submitted by Patrick L. Shabram on behalf of Lamorinda Wine Growers Association. Wineries and growers that are members of the Lamorinda Wine Growers Association are listed in Exhibit M: Lamorinda Wine Growers Association. This petition contains all the information required to establish an AVA in accordance with Title 27 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) part 9.3. List of unique characteristics: All viticulture limited to moderate-to-moderately steep slopes carved from of uplifted sedimentary rock. Geological rock is younger, less resistant sedimentary rock than neighboring rock. Other surrounding areas are areas of active deposition. Soils in Lamorinda have higher clay content, a result of weathered claystone. The topography allows for shallow soils and good runoff, reducing moisture held in the soil. Despite its position near intrusions of coastal air, Lamorinda is protected from coastal cooling influences. Daytime microclimates are more dependent on slope, orientation, and exposure, leading to a large number of microclimates. -

(SLO Coast) Viticultural Area

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 191 / Thursday, October 1, 2020 / Proposed Rules 61899 (3) Proceed along the Charles City DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Background on Viticultural Areas County boundary, crossing onto the TTB Authority Petersburg, Virginia, map and Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade continuing along the Charles City Bureau Section 105(e) of the Federal Alcohol County boundary to the point where it Administration Act (FAA Act), 27 intersects the Henrico County boundary 27 CFR Part 9 U.S.C. 205(e), authorizes the Secretary at Turkey Island Creek; then of the Treasury to prescribe regulations for the labeling of wine, distilled spirits, (4) Proceed north-northeasterly along [Docket No. TTB–2020–0009; Notice No. 194] and malt beverages. The FAA Act the concurrent Henrico County–Charles provides that these regulations should, City County boundary to its intersection among other things, prohibit consumer RIN 1513–AC59 with the Chickahominy River, which is deception and the use of misleading concurrent with the New Kent County Proposed Establishment of the San statements on labels, and ensure that boundary; then Luis Obispo Coast (SLO Coast) labels provide the consumer with (5) Proceed northwesterly along the Viticultural Area adequate information as to the identity Chickahominy River–New Kent County and quality of the product. The Alcohol boundary, crossing onto the Richmond, AGENCY: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Virginia, map to its intersection with the Trade Bureau, Treasury. (TTB) administers the FAA Act Hanover County boundary; then pursuant to section 1111(d) of the ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. -

PDF Format Download

May 2019 A WINE ENTHUSIAST’S MONTHLY JOURNEY THROUGH MONTEREY’S WINE COUNTRY Do you ever get confused when staring at the label on the front of a wine bottle? It’s perfectly okay to admit, as it certainly can be confusing. This STORE HOURS is definitely true when we try deciphering labels from foreign countries. References to castles and countries on French wine bottles? Italian labels A Taste of Monterey claiming that the wine inside is “classic?” And something that looks like Cannery Row “reserve” on some Spanish bottles? Even our wine labels in the States can be Sun-Thu 11am-7pm unfamiliar if you don’t know what to look for…so, what does it all mean? Let’s try and make some sense of these crazy labels! Fri-Sat 11am-8pm* U.S.A. Food service begins at 11:30am daily We all are aware of a wine being from California or Washington State or New *No new member tastings York State, but our labeling system after 6pm provides finer details if we look closer. For example, a bottle with a generic “California” label means that the grapes for that wine could have been sourced from throughout Californian vineyards. If a specific county in California is identified, then you know that the grapes were sourced from that particular county. Next, if an American Viticultural Area (AVA) is listed on the bottle’s label, one is informed that the majority of the grapes originated within that particular AVA. However, note that this could encompass multiple counties. For example, the Central Coast AVA includes portions of six Californian counties, including Monterey. -

MKF RESEARCH Economic Impact of Wine and Winegrapes in the Paso Robles AVA and Greater San Luis Obispo County 2007

MKF RESEARCH ECONOMIC IMPACT OF WINE AND WINEGRAPES IN THE PASO ROBLES AVA AND GREATER SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY 2007 Sponsored by LLC MKF RESEARCH ECONOMIC IMPACT OF WINE AND WINEGRAPES IN THE PASO ROBLES AVA AND GREATER SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY 2007 Thank you to our sponsors LLC Copyright ©2007 by MKF Research LLC The Wine Business Center, 899 Adams Street, Suite E, St. Helena, California 94574 (707) 963-9222 www.mkfresearch.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of MKF Research LLC. ECONOMIC IMPACT OF WINE AND GRAPES IN THE PASO ROBLES AVA AND GREATER SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights ...................................................................................................3 Executive Summary...................................................................................5 The Economic Impact of Wine and Grapes in Greater San Luis Obispo County ...........................................................................8 Allied Industries ................................................................................8 Employment ......................................................................................9 Wineries in San Luis Obispo County ..............................................10 Growing Grapes in San Luis Obispo County..................................11 The Economic Impact of Wine and Grapes in the Paso Robles AVA ....................................................................................14 -

What Proposed Revisions to Wine Labeling Requirements Mean for Growers, Producers, and Consumers Deborah Soh

Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law Volume 13 | Issue 2 Article 7 5-1-2019 Something to Wine About: What Proposed Revisions to Wine Labeling Requirements Mean for Growers, Producers, and Consumers Deborah Soh Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, Marketing Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Deborah Soh, Something to Wine About: What Proposed Revisions to Wine Labeling Requirements Mean for Growers, Producers, and Consumers, 13 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. 491 (2019). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol13/iss2/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. SOMETHING TO WINE ABOUT: WHAT PROPOSED REVISIONS TO WINE LABELING REQUIREMENTS MEAN FOR GROWERS, PRODUCERS, AND CONSUMERS ABSTRACT Title 27 of the Code of Federal Regulations governs the standards for the information that is printed on wine bottle labels, including the appellation of origin. Currently, however, wines are exempt from these regulations if they will not be introduced in interstate commerce. There is a proposed amendment to the Code that would bring all wines, regardless of whether they are sold interstate or solely intrastate, under the federal standards for wine labeling. Between the current system, which permits exempt wines to sidestep the regulations, and the proposal, which would exact strict standards of compliance uniformly, lies a middle-ground approach that would apply federal regulation to all wines while also defining the distinction between appellations of origin and identification of grape sources. -

DEPARTMENT of the TREASURY Alcohol And

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 08/25/2021 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2021-18208[Billing Code: 4810–31–P], and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau 27 CFR Part 9 [Docket No. TTB–2020–0007; T.D. TTB–172; Ref: Notice No. 192] RIN: 1513–AC55 Modification of the Boundaries of the Santa Lucia Highlands and Arroyo Seco Viticultural Areas AGENCY: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, Treasury. ACTION: Final rule; Treasury decision. SUMMARY: The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) is modifying the boundaries of the “Santa Lucia Highlands” viticultural area and the adjacent “Arroyo Seco” viticultural area in Monterey County, California. The boundary modifications include two separate actions—removing approximately 376 acres from the Santa Lucia Highlands viticultural area, and removing 148 acres from the Arroyo Seco viticultural area and placing them entirely within the Santa Lucia Highlands viticultural area. The Santa Lucia Highlands and Arroyo Seco viticultural areas and the modification areas are located entirely within the existing Monterey and Central Coast viticultural areas. TTB designates viticultural areas to allow vintners to better describe the origin of their wines and to allow consumers to better identify wines they may purchase. DATES: This final rule is effective [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS FROM DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Karen A. Thornton, Regulations and Rulings Division, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, 1310 G Street NW., Box 12, Washington, DC 20005; phone 202–453–1039, ext. -

Chardonnay Tasting Notes

Our Home CALIFORNIA’S CENTRAL COAST is known for its temperamental conditions and great diversity of wines. Grapes grow slowly in the cool, windy terroir and rich alluvial soil to develop dense and more intense fruit characteristics. The Central Coast AVA (American Viticultural Area) is large and spans from Santa Barbara County in the south to the San Francisco Bay Area in the north. Central Coast includes six counties and within this AVA there are several smaller appellations that share the same cooling inf uence from the Pacif c Ocean. Hidden Crush grapes are hand-selected primarily from vineyards in Monterey County, Santa Lucia Highlands, Paso Robles and Santa Barbara. We source across the region to take advantage of the broad variety of f avors, aromas and textures that the many micoclimates offer. This allows us to create the best possible wine from Central Coast blended varietals. Chardonnay SANTA LUCIA HIGHLANDS AVA is a protected, fertile area in the Santa Lucia Mountains, above the Salinas Valley. The region enjoys cool morning fog and breezes from Monterey Bay followed by warm afternoons with direct southern exposure. We source our grapes from the Bianchi Bench Vineyard. This very cool area benef ts from perfect ripening conditions to produce citrus f avors, good structure, good acidity and mineral character. MONTEREY AVA runs from its northernmost point, north of Monterey Bay, 100 miles south to Paso Robles. The north is cool with a very long growing season. Overall, daytime temperatures rarely exceed 75°F, but may occasionally reach 100°F in the south. Soil can be alluvial, gravely loam, or sandy and requires extensive irrigation from the Salinas River. -

2017 the Toast of the Coast Wine Results Medal Special Awards Score Pts Brand Vintage Wine Appellation Suggested Retail Price Do

2017 The Toast of the Coast Wine Results Score Suggested Medal Special Awards Pts Brand Vintage Wine Appellation Retail Price Double Gold 2017 The Toast of the Coast, Best of Napa Valley AVA, Best Bordeaux Style Blend; 96 Sodaro Estate Winery 2007 Estate Blend, Estate Grown Napa Valley $ 110.00 Double Gold Best Cabernet Sauvignon 95 Cabana Wines 2014 RISK Napa Valley; Oakville $ 100.00 Double Gold Best of Paso Robles AVA, Best Red Blend 95 Cirque du Vin 2013 Cirque Du Vin Paso Robles $ 19.00 Double Gold Best Cabernet Franc 95 Darjean Jones 2014 Cabernet Franc, Stagecoach Vineyard Napa Valley $ 74.00 Double Gold Best of Temecula Valley AVA, Best Arneis 95 Hart Winery 2016 Arneis Temecula Valley $ 28.00 Double Gold 95 Miguel Aime Pouget 2016 Malbec Mendoza $ 18.00 Double Gold Best California Appellation, Best Verdelho 95 South Coast Winery 2016 Verdehlo California $ 18.00 Double Gold Best of Washington, Best Carmenere 95 Tertulia Cellars 2013 Carmenere, Phinny Hill Vineyard Horse Heaven Hills $ 40.00 Double Gold Best Red Blend 94 Alexander Valley Vineyards 2014 Homestead Red Blend Alexander Valley; Sonoma County $ 20.00 Double Gold 94 Andãs 2016 Malbec,Reserva Mendoza $ 20.00 Double Gold 94 Avinodos 2014 Cabernet Sauvignon Coombsville $ 58.00 Double Gold 94 Barefoot Bubbly NV Moscato Spumante California $ 9.99 Double Gold Best Sweet Sparkling Wine 94 Barefoot Bubbly NV Pink Moscato California $ 9.99 Double Gold Best of Dry Creek Valley AVA, Best Petite Sirah (Tie) 94 Beach House Winery 2012 Petite Sirah Dry Creek Valley $ 38.00 Double Gold -

Notice No. 85, Proposed Expansion of the Paso Robles

40474 Federal Register / Vol. 73, No. 136 / Tuesday, July 15, 2008 / Proposed Rules and perform other time-sensitive acts falling filing the claim. Section 6511(a) requires that ADDRESSES: You may send comments to on or after September 30, 2008, and on or a claim for refund be filed within three years one of the following addresses: before December 2, 2008, has been postponed from the time the return was filed or two • http://www.regulations.gov (via the to December 2, 2008. years from the time the tax was paid, online comment form for this notice as (iii) Because A’s principal residence is in whichever period expires later. Section posted within Docket No. TTB–2008– County W, A is an affected taxpayer. Because 6511(b)(2)(A) includes within the lookback October 15, 2008, the extended due date to period the period of an extension of time to 0005 at ‘‘Regulations.gov,’’ the Federal e-rulemaking portal); or file A’s 2007 Form 1040, falls within the file. Thus, payments that H and W made on • postponement period described in the IRS’s or after May 30, 2008, would be eligible to Director, Regulations and Rulings published guidance, A’s return is timely if be refunded. Since the period from April 15, Division, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and filed on or before December 2, 2008. 2008, to May 30, 2008, is disregarded, Trade Bureau, P.O. Box 14412, However, the payment due date, April 15, payments H and W made on April 15, 2008 Washington, DC 20044–4412. -

Estate-Driven Wines from the Central Coast

Estate-driven wines from the Central Coast THE WHAT FEATURES AND BENEFITS Located in Santa Barbara County’s quaint seaside town of FEATURE BENEFIT Summerland, Summerland Winery has been producing quality, Established Santa Barbara Winery Drives authenticity and positive estate-driven wines derived from renowned vineyards across with true sense of place brand imagery California’s coastal growing regions since its founding in 2002. Elevated package Drives brand equity and quality It’s always summer in Summerland. Drink it in. for value ratios THE WHO AND WHEN Central Coast AVA A step above the competitive set 30-50 Moderately affluent males and females, skew Aggressive by the glass pricing Drives trial, awareness and affinity female. Everyday wine drinkers, looking for more classic packaging and imagery. Dines out often, wine as meal enhancer and casual beverage. VARIETAL Chardonnay Pinot Noir Cabernet Sauvignon Sauvignon Blanc Appellation Central Coast Central Coast Central Coast Central Coast Tasting Notes This bright Chardonnay displays aromas This is a very expressive wine aromatically, Our Cabernet Sauvignon from the broad A rich bouquet of pear, pineapple, and lime of freshly sliced Golden Delicious apples with lychee, cranberry, kola, raspberry, red California appellation shows quality through blossom give way to a palate marked with with touches of toasty oak and pear. On the cherries abounding with hints of cinnamon careful selection of great vineyard fruit. The nose fresh, tropical fruit flavors with hints of palate flavors are clean and balanced in this and clove, wildflower honey, and cacao. is pleasing with hints of blackberry, black currant citrus and lychee nut.