What Proposed Revisions to Wine Labeling Requirements Mean for Growers, Producers, and Consumers Deborah Soh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

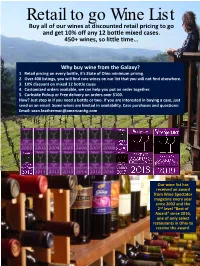

Retail to Go Wine List Buy All of Our Wines at Discounted Retail Pricing to Go and Get 10% Off Any 12 Bottle Mixed Cases

Retail to go Wine List Buy all of our wines at discounted retail pricing to go and get 10% off any 12 bottle mixed cases. 450+ wines, so little time… Why buy wine from the Galaxy? 1. Retail pricing on every bottle, it's State of Ohio minimum pricing. 2. Over 400 listings, you will find rare wines on our list that you will not find elsewhere. 3. 10% discount on mixed 12 bottle cases 4. Customized orders available, we can help you put an order together. 5. Curbside Pickup or Free delivery on orders over $100. How? Just stop in if you need a bottle or two. If you are interested in buying a case, just send us an email. Some wines are limited in availability. Case purchases and questions: Email: [email protected] Our wine list has received an award from Wine Spectator magazine every year since 2002 and the 2nd level “Best of Award” since 2016, one of only select restaurants in Ohio to receive the award. White Chardonnay 76 Galaxy Chardonnay $12 California 87 Toasted Head Chardonnay $14 2017 California 269 Debonne Reserve Chardonnay $15 2017 Grand River Valley, Ohio 279 Kendall Jackson Vintner's Reserve Chardonnay $15 2018 California 126 Alexander Valley Vineyards Chardonnay $15 2018 Alexander Valley AVA,California 246 Diora Chardonnay $15 2018 Central Coast, Monterey AVA, California 88 Wente Morning Fog Chardonnay $16 2017 Livermore Valley AVA, California 256 Domain Naturalist Chardonnay $16 2016 Margaret River, Australia 242 La Crema Chardonnay $20 2018 Sonoma Coast AVA, California (WS89 - Best from 2020-2024) 241 Lioco Sonoma -

Spanish Wine & Extra Virgin Olive Oil Selection

Spanish Wine & Extra Virgin Olive Oil Selection ORIGIN ORIGIN FOOBESPAIN INTERNATIONAL trajectory has always been marked by a continuous learning of different cultures and international markets and the search for wine producers with an interesting and suitable portfolio for these markets. The major premise of FOOBESPAIN INTERNATIONAL is to harness this market knowledge to offer a wide range of innovative wine brands tailored to our costumers needs. CONTACT BUSINESS PHILOSOPHY FOOBESPAIN INTERNACIONAL devotes its business to commercial representation of [email protected] wineries at international and national level. Foobespain has a long marketing and sale +34 926 513 167 of wine with high added value which, in turn, great value for the price. FOOBESPAIN Avenida de la Mancha, 80 6º C already has an experience of more than 10 years as a commercial representative of 02008 Albacete - Spain wineries and currently exports more than 25 countries to international level. It also offers commercial and marketing support to its customers throughout the world. DEHESA DEL CARRIZAL Dehesa del Carrizal is a Vino de Pago, the highest category accord- ing The oldest grapevines of Cabernet Sauvignon have grown at Dehesa to Spanish wine law. It is a DOP (Denominación de Origen Protegida - del Carrizal since 1987. They were later joined by Syrah, Merlot. Protected Designation of Origin) reserved for those few wineries and The acid soils of the siliceous Mediterranean mountains, a humid vineyards which carry out the whole process -from the grape to the climate and 800 metres of altitude create the perfect particular micro bottle- within the limits of the Pago or estate. -

Varietal Appellation Region Glera/Bianchetta

varietal appellation region 14 prairie organic vodka, fever tree ginger glera/bianchetta veneto, Italy 13 | 52 beer,cucumber, lime merlot/incrocio manzoni veneto, Italy 13 | 52 14 prairie organic gin, rhubarb, lime, basil 14 brooklyn gin, foro dry vermouth, melon de bourgogne 2016 loire, france 10 | 40 bigallet thym liqueur, lemon torrontes 2016 salta, argentina 10 | 40 14 albarino 2015 rias baixas, spain 12 | 48 foro amaro, cointreau, aperol, prosecco, orange dry riesling 2015 finger lakes, new york 13 | 52 14 pinot grigio 2016 alto-adige, italy 14 | 56 milagro tequila, jalapeno, lime, ancho chili salt chardonnay 2014 napa valley, california 14 | 56 14 sauvignon blanc 2015 loire, france 16 | 64 mount gay silver rum, beet, lime 14 calvados, bulleit bourbon, maple syrup, angostura bitters, orange bitters gamay 2016 loire, france 10 | 40 grenache/syrah 2016 provence, france 14 | 56 spain 8 cabernet/merlot 2014 bordeaux, france 10 | 40 malbec 2013 mendoza, argentina 13 | 52 illinois 8 grenache 2014 rhone, france 13 | 52 california 8 sangiovese 2014 tuscany, Italy 14 | 56 montreal 11 pinot noir 2013 central coast, california 16 | 64 massachusetts 10 cabernet sauvignon 2015 paso robles, california 16 | 64 Crafted to remove gluten pinot noir 2014 burgundy, france 17 | 68 massachusetts 7 new york 12 chardonnay/pinot noir NV new york 8 epernay, france 72 new york 9 pinot noir/chardonnay NV ay, france 90 england 10 2014 france 25 (750 ml) friulano 2011 friuli, Italy 38 gruner veltliner 2016 weinviertel, austria 40 france 30 (750 ml) sauvignon -

Loire Valley

PREVIEWCOPY Introduction Previewing this guidebook? If you are previewing this guidebook in advance of purchase, please check out our enhanced preview, which will give you a deeper look at this guidebook. Wine guides for the ultra curious, Approach Guides take an in-depth look at a wine region’s grapes, appellations and vintages to help you discover wines that meet your preferences. The Loire Valley — featuring a compelling line-up of distinctive grape varieties, high quality winemaking and large production volumes — is home to some of France’s most impressive wines. Nevertheless, it remains largely overlooked by the international wine drinking public. This makes the region a treasure trove of exceptional values, just waiting to be discovered. What’s in this guidebook • Grape varieties. We describe the Loire’s primary red and white grape varieties and where they reach their highest expressions. • Vintage ratings. We offer a straightforward vintage ratings table, which affords high-level insight into the best and most challenging years for wine production. • A Loire Valley wine label. We explain what to look for on a Loire Valley wine label and what it tells you about what’s in the bottle. • Map and appellation profiles. Leveraging our map of the region, we provide detailed pro- files of appellations from all five of the Loire’s sub-regions (running from west to east): Pays Nantais, Anjou, Saumur, Touraine and Central Vineyards. For each appellation, we describe the prevailing terroir, the types of wine produced and what makes them distinctive. • A distinctive approach. This guidebook’s approach is unique: rather than tell you what specific bottle of wine to order by providing individual bottle reviews, it gives the information you need to make informed wine choices on any list. -

September 2000 Edition

D O C U M E N T A T I O N AUSTRIAN WINE SEPTEMBER 2000 EDITION AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD AT: WWW.AUSTRIAN.WINE.CO.AT DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition Foreword One of the most important responsibilities of the Austrian Wine Marketing Board is to clearly present current data concerning the wine industry. The present documentation contains not only all the currently available facts but also presents long-term developmental trends in special areas. In addition, we have compiled important background information in abbreviated form. At this point we would like to express our thanks to all the persons and authorities who have provided us with documents and personal information and thus have made an important contribution to the creation of this documentation. In particular, we have received energetic support from the men and women of the Federal Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management, the Austrian Central Statistical Office, the Chamber of Agriculture and the Economic Research Institute. This documentation was prepared by Andrea Magrutsch / Marketing Assistant Michael Thurner / Event Marketing Thomas Klinger / PR and Promotion Brigitte Pokorny / Marketing Germany Bertold Salomon / Manager 2 DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Austria – The Wine Country 1.1 Austria’s Wine-growing Areas and Regions 1.2 Grape Varieties in Austria 1.2.1 Breakdown by Area in Percentages 1.2.2 Grape Varieties – A Brief Description 1.2.3 Development of the Area under Cultivation 1.3 The Grape Varieties and Their Origins 1.4 The 1999 Vintage 1.5 Short Characterisation of the 1998-1960 Vintages 1.6 Assessment of the 1999-1990 Vintages 2. -

June 2016 Wine Club Write.Pages

HIGHLAND FINE WINE JUNE 2016 HALF CASE - RED Domaine Landron Chartier ‘Clair Mont’ – Loire Vin de Pays, France (Mixed & Red Club) $17.99 The ‘Clair Mont’ is made up of mostly Cabernet Franc with a bit of Cabernet Sauvignon in the blend. Cabernet Franc is grown all over the Loire Valley and is a parent of its more famous progeny, Cabernet Sauvignon. Cabernet Franc in the Loire Valley is much lighter and fresh. The grape is early ripening and as a result has typically lower sugar levels at harvest, which producers lower alcohol wines. This wine is perfect for Cabernet Sauvignon drinkers who want lighter wines during the summer. It has all of the flavor components of Cabernet Sauvignon without the full tannins. This wine is great for grilling burgers and hotdogs or with Flank steak. Ryan Patrick Red – Columbia Valley, Washington (Mixed & Red Club) $11.99 This red is a blend of 71% Cabernet Sauvignon, 25% Merlot, 4% Malbec, and 1% Syrah. It is a blend typical of Columbia Valley which is known more for Bordeaux varietals such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. In fact Columbia Valley and Bordeaux are on roughly the same longitude, which means they have some similar climactic traits. Like Bordeaux, Columbia Valley is known for a more rounded style of red wine compared to the sun drenched wines of Napa Valley. This blend has a smooth texture with raspberry and dark cherry flavors, and has a dry, fruity finish. I like this wine with a slight chill to bring out the fruit. Calina Carmenere Reserva – Valle del Maule, Chile (Mixed & Red Club) $10.99 Carmenere has become the varietal of choice from Chile. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

J. Wilkes Wines Central Coast

Gold Wine Club Vol 28i12 P TheMedal WinningWine Wines from California’s Best Family-Ownedress Wineries. J. Wilkes Wines Central Coast Gold Medal Wine Club The Best Wine Club on the Planet. Period. J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red” Blend Paso Robles Highlands District, California 1,000 Cases Produced The J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red” is a blend of 90% Barbera and 10% Lagrein from the renowned Paso Robles Highlands District on California’s Central Coast. This District, which is the most southeast sub appellation within the Paso Robles AVA, is an absolutely fantastic place to grow wine grapes, partly due to its average 55 degree temperature swing from day to night (the highest diurnal temperature swing in the United States!), and also in part to its combination of sandy and clay soils that promote very vigorous vines. The high temperature swing, by the way, crafting bold, complex red blends like the J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’s Red.” This wine opens with incredibly seductive slows the ripening rate of the fruit on the vine and allows flavors to develop, which is especially important when and just the right balance of bright, deep, and elegant nuances. Suggested food pairings for the J. Wilkes 2017 “Kent’saromas Red”of blackberry, include barbecued huckleberry, steak, and pork, freshly or beefberry stew. pie. AgedThe palate in oak. is Enjoy dry, but now very until fruity 2027. with dark berry flavors Gold Medal Special Selection J. Wilkes 2016 Chardonnay Paso Robles Highlands District, California 1,000 Cases Produced J. Wilkes’ 2016 Chardonnay also comes from the esteemed Paso Robles Highlands District, a region that may be dominated by red wine grapes, but the Chardonnay grown here is well-respected and offers some 2016 Chardonnay opens with dominating aromas of ripe pear, green apple and lime zest. -

Cabernet Sauvignon Thrives in J. Lohr's Paso Robles Vineyards On

Cabernet sauvignon thrives in J. Lohr’s Paso Robles vineyards on the Estrella plateau on the east side of Highway 101. aso Robles may be America’s most dynamic wine region - and its most diverse. Splendid old-vine zinfandel, ageworthy and elegant cabernet Psauvignon, spicy yet supple pinot noir, and almost any white or red variety, from pinot grigio to petite syrah, are made here. World-class bottlings of viognier, roussanne, marsanne, syrah, grenache, and mourvèdre, either as beautifully inte- grated blends or as stand-alone varietals, proudly bear the Paso Robles name. Central to the region’s dynamism is an environment that is ideal for growing quality grapes and a core of talented producers, winemakers, and growers who have been attracted by the promise of Paso Robles. Discovering Paso Robles Although many wine lovers have discovered the charms of the area’s wines, it remains unknown to some and few would be able to place Paso Robles (“pass of the oaks” in Spanish) on a map of California. The town is located roughly halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, and the Paso Robles American Viticultural Area (AVA), a heptagon- shaped area of more than 650,000 acres, covers much of northern San Luis Obispo County. Within this vast expanse are at least eight distinct subregions: the most important are the “Estrella Triangle” or plateau on the east side of Highway 101, the old- vine vineyards near Templeton established by Italian immigrants in the 1920s, and the Adelaida hills area near the western border of the AVA, west of the town of Paso Robles. -

Varieties Common Grape Varieties

SPECIALTY WINES AVAILABLE AT THESE LOCATIONS NH LIQUOR COMMISSION WINE EDUCATION SERIES WINE & REGIONS OF THE WORLD Explore. Discover. Enjoy. Varieties COMMON GRAPE VARIETIES Chardonnay (shar-doe-nay´) Famous Burgundy grape; produces medium to full bodied, dry, complex wines with aromas and tastes of lemon, apple, pear, or tropical fruit. Wood aging adds a buttery component. Sauvignon Blanc (so-vin-yawn´ blawn) Very dry, crisp, light-to-medium-bodied bright tasting wine with flavors of gooseberry, citrus and herbs. Riesling (reese´-ling) This native German grape produces light to medium- bodied, floral wines with intense flavors of apples, elcome to the peaches and other stone fruits. It can range from dry world of wine. to very sweet when made into a dessert style. One of the most appeal- Gewürztraminer (ge-vurtz´-tram-mih´-nur) ing qualities of wine is Spicy, medium-bodied, fresh, off-dry grape; native to the Alsace Region of France; also grown in California. the fact that there is such an Goes well with Asian foods. enormous variety to choose Pinot Gris (pee´-no-gree) from and enjoy. That’s why Medium to full bodied depending on the region, each New Hampshire State produces notes of pear and tropical fruit, and has a full finish. Liquor and Wine Outlet Store of- Pinot Blanc (pee´-no-blawn) fers so many wines from all around Medium-bodied, honey tones, and a vanilla finish. the world. Each wine-producing region Chenin Blanc (shay´-nan-blawn) creates varieties with subtle flavors, Off-dry, fruity, light-bodied grape with a taste of melon textures, and nuances which make them and honey; grown in California and the Loire Valley. -

Federal Register/Vol. 77, No. 56/Thursday, March 22, 2012/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 56 / Thursday, March 22, 2012 / Rules and Regulations 16671 litigation, establish clear legal DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY • The United States; standards, and reduce burden. • A State; Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade • Two or no more than three States Executive Order 13563 Bureau which are all contiguous; The Department of State has • A county; considered this rule in light of 27 CFR Part 4 • Two or no more than three counties Executive Order 13563, dated January in the same State; or [Docket No. TTB–2010–0007; T.D. TTB–101; • A viticultural area as defined in 18, 2011, and affirms that this regulation Re: Notice No. 110] is consistent with the guidance therein. § 4.25(e). RIN 1513–AB58 Section 4.25(b)(1) states that an Executive Order 13175 American wine is entitled to an Labeling Imported Wines With The Department has determined that appellation of origin other than a Multistate Appellations this rulemaking will not have tribal multicounty or multistate appellation, implications, will not impose AGENCY: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and or a viticultural area, if, among other substantial direct compliance costs on Trade Bureau, Treasury. requirements, at least 75 percent of the Indian tribal governments, and will not ACTION: Final rule; Treasury decision. wine is derived from fruit or agricultural preempt tribal law. Accordingly, products grown in the appellation area Executive Order 13175 does not apply SUMMARY: The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax indicated. Use of an appellation of to this rulemaking. and Trade Bureau is amending the wine origin comprising two or no more than labeling regulations to allow the three States which are all contiguous is Paperwork Reduction Act labeling of imported wines with allowed under § 4.25(d) if: This rule does not impose any new multistate appellations of origin. -

J. Wilkes Wines Central Coast

GOLD WINE CLUB VOLUME 26 ISSUE 09 P TheMedal WinningWine Wines from California’s Best Family-Ownedress Wineries. J. Wilkes Wines Central Coast GOLD MEDAL WINE CLUB The Best Wine Club on the Planet. Period. 2013 “CHANDRA’S RESERVE’ PINOT NOIR CENTRAL COAST 657 Cases Produced Produced from a selection of top vineyards in the Santa Maria Valley and Monterey AVA’s the J. Wilkes 2013 “Chandra’s Reserve” Pinot Noir beautifully blends the best characteristics of Central Coast Pinot. Medium garnet red in color, the 2013 “Chandra’s Reserve” Pinot Noir opens with amazingly complex aromas of ripe cherry, raspberry, baking spice, earthy leather, and the slightest hint of sage and wet stone. The palate is bright growingand fruity regions. with excellent The J. Wilkes fresh 2013 acidity “Chandra’s and persistent Reserve” flavors Pinot of Noir red is berry a food fruits friendly and winebright as cherry.well, pairing Lively with and delicious from start to finish, this wine exemplifies classic Central Coast character showing the elegance of both mignon. Enjoy now until 2021. everything from white fish, to strong artisanal cheeses, a grilled cheese sandwich and tomato soup, or even filet GOLD MEDAL SPECIAL SELECTION 2013 “CHANDRA’S RESERVE” CHARDONNAY CENTRAL COAST 456 Cases Produced A delicious and special Chardonnay blend from top vineyard sites on California’s Central Coast, the J. Wilkes 2013 “Chandra’s Reserve” Chardonnay might just be your next go-to bottle of white wine. Medium straw- yellow in color with brilliant clarity, this Chardonnay offers hints of chalky minerality on the nose, framed by aromas of green apple, quince, pear, lime blossom, caramel, and tropical fruit.