A Single Population of Red Globular Clusters Around the Massive Compact Galaxy NGC 1277

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astronomie in Theorie Und Praxis 8. Auflage in Zwei Bänden Erik Wischnewski

Astronomie in Theorie und Praxis 8. Auflage in zwei Bänden Erik Wischnewski Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Beobachtungen mit bloßem Auge 37 Motivation 37 Hilfsmittel 38 Drehbare Sternkarte Bücher und Atlanten Kataloge Planetariumssoftware Elektronischer Almanach Sternkarten 39 2 Atmosphäre der Erde 49 Aufbau 49 Atmosphärische Fenster 51 Warum der Himmel blau ist? 52 Extinktion 52 Extinktionsgleichung Photometrie Refraktion 55 Szintillationsrauschen 56 Angaben zur Beobachtung 57 Durchsicht Himmelshelligkeit Luftunruhe Beispiel einer Notiz Taupunkt 59 Solar-terrestrische Beziehungen 60 Klassifizierung der Flares Korrelation zur Fleckenrelativzahl Luftleuchten 62 Polarlichter 63 Nachtleuchtende Wolken 64 Haloerscheinungen 67 Formen Häufigkeit Beobachtung Photographie Grüner Strahl 69 Zodiakallicht 71 Dämmerung 72 Definition Purpurlicht Gegendämmerung Venusgürtel Erdschattenbogen 3 Optische Teleskope 75 Fernrohrtypen 76 Refraktoren Reflektoren Fokus Optische Fehler 82 Farbfehler Kugelgestaltsfehler Bildfeldwölbung Koma Astigmatismus Verzeichnung Bildverzerrungen Helligkeitsinhomogenität Objektive 86 Linsenobjektive Spiegelobjektive Vergütung Optische Qualitätsprüfung RC-Wert RGB-Chromasietest Okulare 97 Zusatzoptiken 100 Barlow-Linse Shapley-Linse Flattener Spezialokulare Spektroskopie Herschel-Prisma Fabry-Pérot-Interferometer Vergrößerung 103 Welche Vergrößerung ist die Beste? Blickfeld 105 Lichtstärke 106 Kontrast Dämmerungszahl Auflösungsvermögen 108 Strehl-Zahl Luftunruhe (Seeing) 112 Tubusseeing Kuppelseeing Gebäudeseeing Montierungen 113 Nachführfehler -

X-Ray and Gamma-Ray Variability of NGC 1275

galaxies Article X-ray and Gamma-ray Variability of NGC 1275 Varsha Chitnis 1,*,† , Amit Shukla 2,*,† , K. P. Singh 3 , Jayashree Roy 4 , Sudip Bhattacharyya 5, Sunil Chandra 6 and Gordon Stewart 7 1 Department of High Energy Physics, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai 400005, India 2 Discipline of Astronomy, Astrophysics and Space Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Indore, Khandwa Road, Simrol, Indore 453552, India 3 Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Mohali, Knowledge City, Sector 81, SAS Nagar, Manauli 140306, India; [email protected] 4 Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Ganeshkhind, Pune 411 007, India; [email protected] 5 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai 400005, India; [email protected] 6 Centre for Space Research, North-West University, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa; [email protected] 7 Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (A.S.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 24 August 2020; Published: 28 August 2020 Abstract: Gamma-ray emission from the bright radio source 3C 84, associated with the Perseus cluster, is ascribed to the radio galaxy NGC 1275 residing at the centre of the cluster. Study of the correlated X-ray/gamma-ray emission from this active galaxy, and investigation of the possible disk-jet connection, are hampered because the X-ray emission, particularly in the soft X-ray band (2–10 keV), is overwhelmed by the cluster emission. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster R

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications Physics and Astronomy 2012 Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster R. Mittal Rochester Institute of Technology J. B. R. Oonk Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Netherlands Gary J. Ferland University of Kentucky, [email protected] A. C. Edge Durham University, UK C. P. O'Dea Rochester Institute of Technology See next page for additional authors Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/physastron_facpub Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Physics Commons Repository Citation Mittal, R.; Oonk, J. B. R.; Ferland, Gary J.; Edge, A. C.; O'Dea, C. P.; Baum, S. A.; Whelan, J. T.; Johnstone, R. M.; Combes, F.; Salomé, P.; Fabian, A. C.; Tremblay, G. R.; Donahue, M.; and H., Russell H., "Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster" (2012). Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications. 29. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/physastron_facpub/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics and Astronomy at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors R. Mittal, J. B. R. Oonk, Gary J. Ferland, A. C. Edge, C. P. O'Dea, S. A. Baum, J. T. Whelan, R. M. Johnstone, F. Combes, P. Salomé, A. C. -

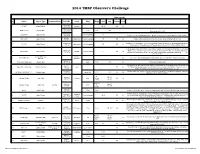

2014 Observers Challenge List

2014 TMSP Observer's Challenge Atlas page #s # Object Object Type Common Name RA, DEC Const Mag Mag.2 Size Sep. U2000 PSA 18h31m25s 1 IC 1287 Bright Nebula Scutum 20'.0 295 67 -10°47'45" 18h31m25s SAO 161569 Double Star 5.77 9.31 12.3” -10°47'45" Near center of IC 1287 18h33m28s NGC 6649 Open Cluster 8.9m Integrated 5' -10°24'10" Can be seen in 3/4d FOV with above. Brightest star is 13.2m. Approx 50 stars visible in Binos 18h28m 2 NGC 6633 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.6m integrated 27' 205 65 Visible in Binos and is about the size of a full Moon, brightest star is 7.6m +06°34' 17h46m18s 2x diameter of a full Moon. Try to view this cluster with your naked eye, binos, and a small scope. 3 IC 4665 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.2m Integrated 60' 203 65 +05º 43' Also check out “Tweedle-dee and Tweedle-dum to the east (IC 4756 and NGC 6633) A loose open cluster with a faint concentration of stars in a rich field, contains about 15-20 stars. 19h53m27s Brightest star is 9.8m, 5 stars 9-11m, remainder about 12-13m. This is a challenge obJect to 4 Harvard 20 Open Cluster Sagitta 7.7m integrated 6' 162 64 +18°19'12" improve your observation skills. Can you locate the miniature coathanger close by at 19h 37m 27s +19d? Constellation star Corona 5 Corona Borealis 55 Trace the 7 stars making up this constellation, observe and list the colors of each star asterism Borealis 15H 32' 55” Theta Corona Borealis Double Star 4.2m 6.6m .97” 55 Theta requires about 200x +31° 21' 32” The direction our Sun travels in our galaxy. -

Long-Term Study of a Gamma-Ray Emitting Radio Galaxy NGC 1275

Long-term study of a gamma-ray emitting radio galaxy NGC 1275 Yasushi Fukazawa (Hiroshima University) 8th Fermi Symposium @ Baltimore 1 Multi-wavelength variability of a gamma- ray emitting radio galaxy NGC 1275 Yasushi Fukazawa (Hiroshima University) 8th Fermi Symposium @ Baltimore 2 Outline Introduction GeV/gamma-ray and TeV studies Radio and gamma-ray connection X-ray and gamma-ray connection Optical/UV and gamma-ray connection Summary and future prospective Papers on NGC 1275 X-ray/gamma-ray studies in 2015-2018 Nustar view of the central region of the Perseus cluster; Rani+18 Gamma-ray flaring activity of NGC1275 in 2016-2017 measured by MAGIC; Magic+18 The Origins of the Gamma-Ray Flux Variations of NGC 1275 Based on Eight Years of Fermi-LAT Observations; Tanada+18 X-ray and GeV gamma-ray variability of the radio galaxy NGC 1275; Fukazawa+18 Hitomi observation of radio galaxy NGC 1275: The first X-ray microcalorimeter spectroscopy of Fe-Kα line emission from an active galactic nucleus; Hitomi+18 Rapid Gamma-Ray Variability of NGC 1275; Baghmanyan+17 Deep observation of the NGC 1275 region with MAGIC: search of diffuse γ-ray emission from cosmic rays in the Perseus cluster; Fabian+15 More papers on radio/optical observations NGC 1275 Interesting and important object for time-domain and multi-wavelength astrophysics Radio galaxies Parent population of Blazars Unlike blazars, their jet is not aligned to the line of sight, beaming is weaker. EGRET: Cen A detection and a hint of a few radio galaxies 3EG catalog: Hartman et al. -

The Stellar Halos of Massive Elliptical Galaxies. Ii

The Astrophysical Journal, 776:64 (12pp), 2013 October 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/776/2/64 C 2013. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE STELLAR HALOS OF MASSIVE ELLIPTICAL GALAXIES. II. DETAILED ABUNDANCE RATIOS AT LARGE RADIUS Jenny E. Greene1,3, Jeremy D. Murphy1,4, Genevieve J. Graves1, James E. Gunn1, Sudhir Raskutti1, Julia M. Comerford2,4, and Karl Gebhardt2 1 Department of Astrophysics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA 2 Department of Astronomy, UT Austin, 1 University Station C1400, Austin, TX 71712, USA Received 2013 June 24; accepted 2013 August 6; published 2013 September 26 ABSTRACT We study the radial dependence in stellar populations of 33 nearby early-type galaxies with central stellar velocity −1 dispersions σ∗ 150 km s . We measure stellar population properties in composite spectra, and use ratios of these composites to highlight the largest spectral changes as a function of radius. Based on stellar population modeling, the typical star at 2Re is old (∼10 Gyr), relatively metal-poor ([Fe/H] ≈−0.5), and α-enhanced ([Mg/Fe] ≈ 0.3). The stars were made rapidly at z ≈ 1.5–2 in shallow potential wells. Declining radial gradients in [C/Fe], which follow [Fe/H], also arise from rapid star formation timescales due to declining carbon yields from low-metallicity massive stars. In contrast, [N/Fe] remains high at large radius. Stars at large radius have different abundance ratio patterns from stars in the center of any present-day galaxy, but are similar to average Milky Way thick disk stars. -

Tev Emission from NGC1275 Viewed by SHALON 15 Year Observations V.G

XVI International Symposium on Very High Energy Cosmic Ray Interactions ISVHECRI 2010, Batavia, IL, USA (28 June 2 July 2010) 1 TeV emission from NGC1275 viewed by SHALON 15 year observations V.G. Sinitsyna, S.I. Nikolsky, V.Y. Sinitsyna P.N. Lebedev Physical Institute, Leninsky pr. 53, Moscow, Russia The Perseus cluster of galaxies is one of the best studied clusters due to its proximity and its brightness. It have also been considered as sources of TeV gamma-rays. The new extragalactic source was detected at TeV energies in 1996 using the SHALON telescopic system. This object was identified with NGC 1275, a giant elliptical galaxy lying at the center of the Perseus cluster of galaxies; its image is presented. The maxima of the TeV gamma-ray, X-ray and radio emission coincide with the active nucleus of NGC 1275. But, the X-ray and TeV emission disappears almost completely in the vicinity of the radio lobes. The correlation TeV with X-ray emitting regions was found. The integral gamma-ray flux of NGC1275 is found to be (0.78 ± 0.13) × 10−12cm−2s−1 at energies > 0.8 TeV. Its energy spectrum from 0.8 to 40 TeV can be approximated by the power law with index k = −2.25 ± 0.10. NGC1275 has been also observed by other experiments: Tibet Array (5TeV) and then with Veritas telescope at energies about 300 GeV in 2009. The recent detection by the Fermi LAT of gamma- rays from the NGC1275 makes the observation of the energy E > 100 GeV part of its broadband spectrum particularly interesting. -

7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19267-5 - Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue Wolfgang Steinicke Index More information Name index The dates of birth and death, if available, for all 545 people (astronomers, telescope makers etc.) listed here are given. The data are mainly taken from the standard work Biographischer Index der Astronomie (Dick, Brüggenthies 2005). Some information has been added by the author (this especially concerns living twentieth-century astronomers). Members of the families of Dreyer, Lord Rosse and other astronomers (as mentioned in the text) are not listed. For obituaries see the references; compare also the compilations presented by Newcomb–Engelmann (Kempf 1911), Mädler (1873), Bode (1813) and Rudolf Wolf (1890). Markings: bold = portrait; underline = short biography. Abbe, Cleveland (1838–1916), 222–23, As-Sufi, Abd-al-Rahman (903–986), 164, 183, 229, 256, 271, 295, 338–42, 466 15–16, 167, 441–42, 446, 449–50, 455, 344, 346, 348, 360, 364, 367, 369, 393, Abell, George Ogden (1927–1983), 47, 475, 516 395, 395, 396–404, 406, 410, 415, 248 Austin, Edward P. (1843–1906), 6, 82, 423–24, 436, 441, 446, 448, 450, 455, Abbott, Francis Preserved (1799–1883), 335, 337, 446, 450 458–59, 461–63, 470, 477, 481, 483, 517–19 Auwers, Georg Friedrich Julius Arthur v. 505–11, 513–14, 517, 520, 526, 533, Abney, William (1843–1920), 360 (1838–1915), 7, 10, 12, 14–15, 26–27, 540–42, 548–61 Adams, John Couch (1819–1892), 122, 47, 50–51, 61, 65, 68–69, 88, 92–93, -

Caldwell Catalogue - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Caldwell catalogue - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Caldwell catalogue From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents The Caldwell Catalogue is an astronomical catalog of 109 bright star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies for observation by amateur astronomers. The list was compiled Featured content by Sir Patrick Caldwell-Moore, better known as Patrick Moore, as a complement to the Messier Catalogue. Current events The Messier Catalogue is used frequently by amateur astronomers as a list of interesting deep-sky objects for observations, but Moore noted that the list did not include Random article many of the sky's brightest deep-sky objects, including the Hyades, the Double Cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884), and NGC 253. Moreover, Moore observed that the Donate to Wikipedia Messier Catalogue, which was compiled based on observations in the Northern Hemisphere, excluded bright deep-sky objects visible in the Southern Hemisphere such [1][2] Interaction as Omega Centauri, Centaurus A, the Jewel Box, and 47 Tucanae. He quickly compiled a list of 109 objects (to match the number of objects in the Messier [3] Help Catalogue) and published it in Sky & Telescope in December 1995. About Wikipedia Since its publication, the catalogue has grown in popularity and usage within the amateur astronomical community. Small compilation errors in the original 1995 version Community portal of the list have since been corrected. Unusually, Moore used one of his surnames to name the list, and the catalogue adopts "C" numbers to rename objects with more Recent changes common designations.[4] Contact Wikipedia As stated above, the list was compiled from objects already identified by professional astronomers and commonly observed by amateur astronomers. -

Magnetic Support of the Optical Emission Line Filaments in NGC 1275 A

Magnetic support of the optical emission line filaments in NGC 1275 A. C. Fabian1, R. M. Johnstone1, J. S. Sanders1, C. J. Conselice2, C. S. Crawford1, J. S. Gallagher III3 & E. Zweibel3,4 1Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK. 2University of Nottingham, School of Physics & Astronomy, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK. 3Department of Astronomy, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA. 4Department of Physics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA. The giant elliptical galaxy NGC 1275, at the centre of the Perseus cluster, is surrounded by a well-known giant nebulosity of emission-line filaments1,2, which are plausibly about >108 yr old3. The filaments are dragged out from the centre of the galaxy by the radio bubbles rising buoyantly in the hot intracluster gas4 before later falling back. They act as dramatic markers of the feedback process by which energy is transferred from the central massive black hole to the surrounding gas. The mechanism by which the filaments are stabilized against tidal shear and dissipation into the surrounding 4×107K gas has been unclear. Here we report new observations that resolve thread-like structures in the filaments. Some threads extend over 6 kpc, yet are only 70 pc wide. We conclude that magnetic fields in the threads, in pressure balance with the surrounding gas, stabilize the filaments, so allowing a large mass of cold gas to accumulate and delay star formation. The images presented here (Figs. 1—4) were taken with the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) on the NASA Hubble Space Telescope (HST) using three filters; F625W in the red contains the Hα line, F550M is mostly continuum and F435W in the blue which highlights young stars. -

Binocular Challenges

This page intentionally left blank Cosmic Challenge Listing more than 500 sky targets, both near and far, in 187 challenges, this observing guide will test novice astronomers and advanced veterans alike. Its unique mix of Solar System and deep-sky targets will have observers hunting for the Apollo lunar landing sites, searching for satellites orbiting the outermost planets, and exploring hundreds of star clusters, nebulae, distant galaxies, and quasars. Each target object is accompanied by a rating indicating how difficult the object is to find, an in-depth visual description, an illustration showing how the object realistically looks, and a detailed finder chart to help you find each challenge quickly and effectively. The guide introduces objects often overlooked in other observing guides and features targets visible in a variety of conditions, from the inner city to the dark countryside. Challenges are provided for viewing by the naked eye, through binoculars, to the largest backyard telescopes. Philip S. Harrington is the author of eight previous books for the amateur astronomer, including Touring the Universe through Binoculars, Star Ware, and Star Watch. He is also a contributing editor for Astronomy magazine, where he has authored the magazine’s monthly “Binocular Universe” column and “Phil Harrington’s Challenge Objects,” a quarterly online column on Astronomy.com. He is an Adjunct Professor at Dowling College and Suffolk County Community College, New York, where he teaches courses in stellar and planetary astronomy. Cosmic Challenge The Ultimate Observing List for Amateurs PHILIP S. HARRINGTON CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521899369 C P.