The Challenge Issued to Bishop Henry Bond Restarick (1854–1933)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Drift Title: Queen Emma Written By: Jerry D

My Drift Title: Queen Emma Written by: Jerry D. Petersen Date: 31 Oct 2018 Article Number: 299-2018-23 Queen Emma Emma Kalanikaumakaʻamano Kaleleonālani Naʻea Rooke (January 2, 1836 – April 25, 1885) Emma was born on January 2, 1836 in Honolulu and was often called Emalani (“royal Emma”). Her father was High Chief George Naʻea and her mother was High Chiefess Fanny Kekelaokalani Young. She was adopted under the Hawaiian tradition of hānai by her childless maternal aunt, Chiefess Grace Kamaʻikuʻi Young Rooke, and her husband, Dr. Thomas C.B. Rooke. High Chief High Chiefess Fanny Dr. Thomas C.B. Rooke, Emma and George Naʻea Kekelaokalani Young Chiefess Grace Kamaʻikuʻi Young Emma’s father Naʻea was the son of High Chief Kamaunu and High Chiefess Kukaeleiki. Kukaeleiki was daughter of Kalauawa, a Kaua’i noble, and she was a cousin of Queen Keōpūolani, the most sacred wife of Kamehameha I. Among Naʻea’s more notable ancestors were Kalanawaʻa, a high chief of Oʻahu, and High Chiefess Kuaenaokalani, who held the sacred kapu rank of Kekapupoʻohoʻolewaikala (so sacred that she could not be exposed to the sun except at dawn). On her mother’s side, Emma was the granddaughter of John Young, Kamehameha I’s British-born military advisor known as High Chief Olohana, and Princess Kaʻōanaʻeha Kuamoʻo. Her maternal grandmother, Kaʻōanaʻeha, was the niece of Kamehameha I. Emma grew up at her foster parents’ English mansion, “The Rooke House”, in Honolulu. Emma was educated at the Royal School, which was established by American missionaries. Other Hawaiian royals attending the school included Emma’s half-sister Mary Paʻaʻāina. -

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

The Records of the Wahiawa Settlement Association (1899-1939)

M-453 Wahiawa Page 1 THE RECORDS OF THE WAHIAWA SETTLEMENT ASSOCIATION (1899-1939) Introduction The Wahiawa Settlement Association was formed in 1898 through the efforts of Mr. B.0. Clark. _The town was called the Wahiawa Colony, or locally known as the California Colony. This colony was the first systematic effort ever made on the island of Oahu by a group of people to demonstrate what can be done to grow a variety of crops and fruits for conunercial purposes. As the name indicates, the colony was largely composed of former residents of California, who had many years experience of fruit growing in California. One of the.main fruits grown was pineapple, and Wahiawa still remains a pineapple growing area today. This collection of records range from accounts, agreements, assets, correspondence, minutes of meetings and various other documents of the Wahiawa Settlement Association. The period covered by the records are the years between 1899 and 1939. Other informa tion on the Association can be found in Subject Index under Wahiawa, and the Wahiawa Settlement Association. Inventory File Folder No. 1 Minutes of Meetings (1900-1930) 2-5 Correspondence (Incoming) A-W (1904-1939) (4 files) - mostly correspondence with Henry Davis as Secretary of Wahiawa Settlement Association 6 Correspondence (Outgoing) (1904-1929) 7 Accounts and Payments (1904-1928) - includes expenditures and receipts 8 Six folders of cash vouchers (1907-1939) 8.1. July 1, 1907 - December 31, 1917 8.2. January 16, 1918 - September 10, 1923 8.3. June 29, 1923 - October 30, 1926 8.4. January 1, 1927 - December 31, 1929 8.5. -

St. James' Episcopal Church

Ke Akua Alaka‘i iā Kākou: The Lord Leads Us St. James’ Episcopal Church Waimea, Hawaii 30 March 1913 to 30 March 2013 CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION A CENTENNIAL HISTORY OF SAINT JAMES’ EPISCOPAL CHURCH WAIMEA, HAWAI’I 30 March 1913 to 30 March 2013 Compiled by The Church History Committee: Babs Kamrow Doris Purdy Laurie Rosa Bob Stern Fr. Guy Piltz, Consultant Jo Amanti Piltz, History Coordinator Collect for Saint James’ Day, July 25: Grant, O merciful God that, as thine holy Apostle Saint James, leaving his father and all that he had without delay was obedient unto the calling of thy Son Jesus Christ, and followed him; so we, forsaking all worldly and carnal affections, may be evermore ready to follow thy holy commandments, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. Book of Common Prayer, 1892 KE AKUA ALAKA’ I Iā Kākou: THE LORD LEADS US. Led by God, a church is an expression of its people and their faith, and the founding of a new church is the result of the confluence of the hopes of holy people, the catalyst of a new priest, and the support of a bishop. In early 1912, all those elements joined in the village of Waimea on the Island of Hawai’i. In the wider world, 1912 was an important year. Woodrow Wilson was elected 26th President of the United States; Sun Yat Sen established the Republic of China; and the Titanic sank in the North Atlantic. On a more modest scale, in Waimea a dedicated group of Episcopalians bought a building and named their fledgling church Saint James’(see Appendix A). -

Sun Yat-Sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i

IRMA TAM SOONG Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i IN DR. SUN YAT-SEN'S four years as a sojourner in Hawai'i (1879— 1883), he is said to have attended three Christian educational insti- tutions: Iolani College, St. Louis College, and Oahu College (Puna- hou School). His three years at Iolani are well authenticated. Whether he ever attended St. Louis cannot be substantiated by school records, but such a possibility exists. As for Oahu College, there is evidence to support the claim, though the time he spent there is not altogether clear. This essay attempts, by delving into the religious backgrounds of the three schools, their beginnings, their locations, and their cur- ricula, to suggest the nature of the imprint a nineteenth-century Christian environment would have made on the mind and heart of a young revolutionist. Much has been made of the Christian influence of Sun's years at Iolani, which led him to seek baptism and thus incur the wrath of his brother-provider, Sun Mei, who cut short Sun's Hawai'i education and sent him back to their native village of Ts'ui-heng in Hsiang- shan, Kwangtung province, for rehabilitation. It is unlikely that there had been any Christian influence in Sun's life before his departure for Hawai'i. It is doubtful that he ever saw a Christian missionary or evangelist while a youth. When the Rev. Frank Damon visited Hsiang-shan district in 1884, he found a chapel in Shih-ch'i, the district seat, and "a little company Irma Tarn Soong is executive director emerita of the Hawaii Chinese History Center in Honolulu. -

News from Molokai

News from Molokai News from Molokai Letters between Peter Kaeo & Queen Emma 1873-1876 Edited with Introduction and Notes by Alfons L. Korn The University Press of Hawaii • Honolulu The photographs of Peter Kaeo and Queen Emma, and Emma’s letter to Peter of May io, 1876, are reproduced herein by permission of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum. Peter’s letter to Emma of July 7, 1874, is reproduced herein by courtesy of the Archives of the State of Hawaii. The pen-and-ink drawing, Honolulu Harbor, 1871, by Alfred Clint is reproduced on the endsheets by courtesy of The Hawaiian Historical Society. Copyright © 1976 by The University Press of Hawaii All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Manufactured in the United States of America Composition by Asco Trade Typesetting Limited, Hong Kong Book and jacket design by Steve Reoutt Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Kaeo, Peter, 1836-1880. News from Molokai, letters between Peter Kaeo and Queen Emma, 1873-1876. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Kaeo, Peter, 1836-1880. 2. Emma, consort of Kamehameha IV, King of the Hawaiian Islands, 1836- 1885. I. Emma, consort of Kamehameha IV, King of the Hawaiian Islands, 1836-1885, joint author. II. Korn, AlfonsL. III. Title. DU627.17.K28A44 996.9'02'0922 76-16823 ISBN 0-8248-0399-X To Laura Contents Preface ix Introduction xi THE CORRESPONDENCE Part One. -

Men of Hawaii a Biographical Reference

...._._.-—vA9:-—.:~ MEN OF HAWAII A biographical record of men of substantial achievement in the Hawaiian Islands VOLUME IV Revised Edited by GEORGE F. NELLIST Published by THE HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN, LTD. Territory of Hawaii I 9 3 O av .M.n.., ;w»$. _._.fim..sm«._ us. 2..M... 9.3%..3;.sfl.. Copyright, 1930, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Limited Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii. U.S.A. FOREWORD “ EN OF HAWAII,’ is the fourth volume of bio graphical records in the regular series which has been published, beginning with l9l7, by The Honolulu Star Bulletin. This series aims to make available for the present, and to preserve for the future, the life stories of leaders in various fields of the Hawaiian Islands. It is a history of community and territorial progress, told in the form of biographical sketches, and the steady demand for the editions of previous years has abundantly illustrated its interest and its value. Both as a record of enterprise and achievement, and as a compilation of chronological facts, “Nlen of Hawaii" has be -comea standard reference work in Hawaii and abroad. Copies are sent all over the world. Libraries in distant cities call for the succeeding editions. Locally, the book is constantly in use. This book is Volume IV of “lVlen of Hawaii.” The first edition was in l9l7, the second in l9Zl, the third in I925. To a certain degree the present edition supplements and com plements “Builders of Hawaii” U925), with which was incorporated that year’s edition of ‘‘Men of Hawaii.” For the broadest coverage of Hawaiian biographical record, "Builders of Hawaii" and this l930 edition of ‘‘Men of Hawaii" should be treated as one work, and so maintained in reference libraries. -

Jjjatuattan ( B Lntrrlt ( E Ljr

1 5 6 3 W 1 L и с. К A V fc . , HONOLULU. jjjatuattan (B lntrrlt (E ljrm ttrlr *For Christ and His Church' The R t. Rev. S. H arrington ідттеее, D.D., S.T.D., Editor V: T h e R e v . E. Tanner Brown, D.D., Associate Editor Entered as second-class matter February 14, 1908, at the post office at Honolulu, Hawaii, under the Act of March 3, 1879. ' Voe. X X V II. H onoeueu, H aw aii, S e ptem b er, 1937 No. 7 THE RIGHT REVEREND S. HARRINGTON LITTELL, D.D., S.T.D., BISHOP OF HONOLULU 2 HAWAIIAN CHURCH CHRONICLE September, 193; CLERGY LIST IOLANI SCHOOL M issio n a r y D istr ic t or H o n o lu lu A CHURCH SCHOOL FOR BOYS Boarding Department and Day School BISHOP Elementary, College Preparatory and Commercial Courses T h e R t . R ev. S. H a rrin g to n L it t e l l , S.T.D., D.D., Bishop’s House, Queen Address inquiries to the Headmaster Emma Square, Honolulu. 1930 Nuuanu and Judd Streets, Honolulu Telephone 4332 PRIESTS The Rev. Canon Douglas Wallace, Retired; Kealakekua, Hawaii. 1905 ST. ANDREW’S PRIORY The Rev. Canon F. N. Cullen, Retired; A CHURCH SCHOOL FOR GIRLS Queen Emma Square, Honolulu. 191І First to Eighth Grades, Inclusive, and High School Course Accredited The Very Rev. Wm. Ault, St. Andrew’s Cathedral, Honolulu. 1897 For particulars apply to the The Rev. Philip Taiji Fukao, Holy Trinity, Honolulu. -

Anglican Church in Hawaii, a Review

Project Canterbury THE PRINCIPLES OF GOVERNMENT OF THE ANGLICAN CHURCH IN HAWAII, TRACED TO THEIR SOURCE, FOR THE SETTLEMENT OF CERTAIN CONTROVERTED QUESTIONS; TO WHICH IS ADDED A REVIEW OF THE PRESENT POSITION OF THE ANGLICAN CHURCH IN THE KINGDOM OF HAWAII BY THE RIGHT REVEREND ALFRED WILLIS, D.D., FOR EIGHTEEN YEARS BISHOP OF HONOLULU. PUBLISHED BY REQUEST OF HIS MAJESTY KING KALAKUA. HONOLULU: ROBERT GRIEVE, STEAM BOOK AND JOB PRINTER, MERCHANT ST. 1890. INTRODUCTION. The following pages have been written in compliance with a request contained in the following letter from His Majesty King Kalakaua, and others holding high positions in His Majesty's Kingdom: TO THE RIGHT REV. ALFRED WILLIS, D.D., Bishop of Honolulu: MY LORD:--Contrary expressions of opinion existing at present relative to matters of church discipline, order, and government: and certain comments having been made respecting the Bishop's position with reference to the other members of the Board of Trustees of the Anglican Church in Hawaii, We, the undersigned being deeply interested in the welfare of the Anglican Church in this Kingdom, respectfully ask Your Lordship to state, in any convenient manner, your views concerning the matters involved, and especially do we urge Your Lordship to define the principles of church government in the Anglican Communion, and to what extent they are applicable in this realm in view of the fact that the Church Laws obtaining in England are not in force in this Kingdom. We remain, faithfully yours, 1 KALAKUA, C. N. SPENCER, J. S. WALKER, C. P. IAUKEA, HENRY SMITH. -

Hawaiian Historical Society

FIRST ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Hawaiian Historical Society. HONOLULU, H. I. 1893. HONOLULU: PRINTED BY THE HAWAIIAN GAZETTE COMPANY. 1893. ex Libris University of Hawaii Library This volume is bound incomplete. It lacks 2d-6th Continued effort is being made to obtain the missing issues. No further effort is being made to obtain the missing issues. PLEASE ASK AT THE REFERENCE DESK IF A MISSING ISSUE IS NEEDED. NOTICE. All those, not members, to whom a copy of this Annual Report is sent, are herewith invited to co-operate with us as Active Members. And all members of the Society are earnestly urged to help forward the object of this Society by increasing the list of Active Members and by such contributions as they may make themselves, or secure from others, in furtherance of the work of the Society. The conditions of membership are election by vote at any regular meeting, the payment of five dollars, as an initiation fee, and an annual membership fee of one dollar. Members who have not received the Society's pub- lications, Nos. 1,2, 3 and 4, are requested to notify the Treas- urer at once. Extra copies may be obtained on application to the Librarian, Dr. C. T. Rodgers, at the Society's room in the Honolulu Library Building. Contribrtions of manuscript copies of any Hawaiian mele or kaao, are earnestly solicited : also, copies of old newspapers : and any Hawaiian books, or books relating to these Islands, or the islands of the Pacific. FIRST ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Hawaiian Historical Society, HONOLULU, H. -

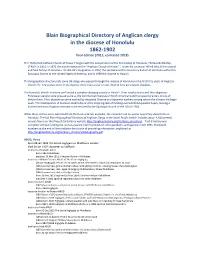

Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican Clergy in the Diocese of Honolulu 1862-1902 Final Edition (2012, Corrected 2018)

Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican clergy in the diocese of Honolulu 1862-1902 final edition (2012, corrected 2018) The “Reformed Catholic Church of Hawai’i” began with the consecration of the first bishop of Honolulu, Thomas Nettleship STALEY in 1861. In 1872 the diocese became the “Anglican Church of Hawai’i”, under his successor Alfred WILLIS the second and final bishop of Honolulu. On WILLIS’s resignation in 1902, the see became the missionary district of Honolulu within the Episcopal Church of the United States of America, and in 1969 the diocese of Hawai'i. This biographical directory lists some 58 clergy who passed through the diocese of Honolulu in the first forty years of Anglican church life. Few priests were in the diocese more than a year or two. Several lives are evasive shadows. The Honolulu church initiative confronted a complex changing society in Hawai’i. Their royal patrons and the indigenous Polynesian people were pressed aside as the commercial interests of North American (and European) planters drove all before them. Their plantations were worked by imported Chinese and Japanese workers among whom the diocese did begin work. The inadequacies of diocesan leadership and the crippling lack of funding overwhelmed quixotic hopes, leaving a divided and worn Anglican remnant to be rescued by the Episcopal church of the USA in 1902. While these entries were compiled from the best evidence available, the compiler had no access to primary documents in Honolulu. The full Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican Clergy in the South Pacific (which includes about 1,500 priests) may be found on the Project Canterbury website http://anglicanhistory.org/nz/blain_directory/ That directory was compiled without funding but with assistance from hundreds of correspondents and agencies from 1991. -

A Century of Chinese Christians a Case Study on Cultural Integration in Hawai‘I Carol C

A Century of Chinese Christians A Case Study on Cultural Integration in Hawai‘i Carol C. Fan Carol C. Fan, “A Century of Chinese Christians: A Case Study on The establishment and development of Chinese churches Cultural Integration in Hawai‘i,” Chinese America: History & relates directly to the political, social, and economic condi- Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society tions of Hawai‘i. The process of acculturation seemed accel- of America (San Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America erated among the early Chinese Christians in Hawai‘i, for with UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 2010), pages 87–93. they were able to take English-language classes, which the missions employed as a pre-evangelical approach to reach the new arrivals. Through the influence of some American InTroduction missionaries, they could get better jobs. However, whether consciously or unconsciously, the he objective of this study is twofold: (1) to advance church leaders exercised the most distinctive feature of the knowledge of the history of the Chinese Protestant Chinese mind, which finds unity in all human experience, TChristian churches in Hawai‘i by examining their whether of the secular or the spiritual realm. Most Chinese founding, development, and contributions from the last quar- Christians continued to celebrate their traditional festivals, to ter of the nineteenth century to the present, and (2) to analyze teach the Chinese language to their children, and above all, how church purposes and practices interacted with historical to enjoy Chinese cuisine, especially on happy occasions. This circumstances to advance or deter the establishment of self- eclectic approach was clearly demonstrated by Luke Aseu, governing and self-supporting Chinese churches.