Centennial Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Million Pounds of Sandalwood: the History of Cleopatra's Barge in Hawaii

A Million Pounds Of Sandalwood The History of CLEOPATRA’S BARGE in Hawaii by Paul Forsythe Johnston If you want to know how Religion stands at the in his father’s shipping firm in Salem, shipping out Islands I can tell you—All sects are tolerated as a captain by the age of twenty. However, he pre- but the King worships the Barge. ferred shore duty and gradually took over the con- struction, fitting out and maintenance of his fam- Charles B. Bullard to Bryant & Sturgis, ily’s considerable fleet of merchant ships, carefully 1 November expanded from successful privateering during the Re volution and subsequent international trade un- uilt at Salem, Massachusetts, in by Re t i re der the new American flag. In his leisure time, B Becket for George Crowninshield Jr., the her- George drove his custom yellow horse-drawn car- m a p h rodite brig C l e o p a t ra’s Ba r g e occupies a unique riage around Salem, embarked upon several life- spot in maritime history as America’s first ocean- saving missions at sea (for one of which he won a going yacht. Costing nearly , to build and medal), recovered the bodies of American military fit out, she was so unusual that up to , visitors heroes from the British after a famous naval loss in per day visited the vessel even before she was com- the War of , dressed in flashy clothing of his pleted.1 Her owner was no less a spectacle. own design, and generally behaved in a fashion Even to the Crowninshields, re n o w n e d quite at odds with his diminutive stature and port l y throughout the region for going their own way, proportions. -

Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons All Theses & Dissertations Student Scholarship 2014 Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840 Anatole Brown MA University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd Part of the Other American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Anatole MA, "Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840" (2014). All Theses & Dissertations. 62. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd/62 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL ENCOUNTERS AND THE MISSIONARY POSITION: NEW ENGLAND’S SEXUAL COLONIZATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, 1778–1840 ________________________ A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF THE ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE AMERICAN AND NEW ENGLAND STUDIES BY ANATOLE BROWN _____________ 2014 FINAL APPROVAL FORM THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE AMERICAN AND NEW ENGLAND STUDIES June 20, 2014 We hereby recommend the thesis of Anatole Brown entitled “Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England’s Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778 – 1840” Be accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Professor Ardis Cameron (Advisor) Professor Kent Ryden (Reader) Accepted Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has been churning in my head in various forms since I started the American and New England Studies Masters program at The University of Southern Maine. -

Select Bibliography

select bibliography primary sources archives Aartsbisschoppelijk Archief te Mechelen (Archive of the Archbishop of Mechelen), Brussels, Belgium. Archive at St. Anthony Convent and Motherhouse, Sisters of St. Francis, Syracuse, NY. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Honolulu. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Leuven, Belgium. Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu. Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. kalaupapa manuscripts and collections Bigler, Henry W. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cannon, George Q. Journals. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cluff, Harvey Harris. Autobiography. Handwritten copy. Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Decker, Daniel H. Mission Journal, 1949–1951. Courtesy of Daniel H. Decker. Farrer, William. Biographical Sketch, Hawaiian Mission Report, and Diary of William Farrer, 1946. Copied from the original and housed in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Gibson, Walter Murray. Diary. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Green, Ephraim. Diary. Microfilm copy, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Halvorsen, Jack L. Journal and correspondence. Copies in possession of the author. Hammond, Francis A. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Hawaii Mission President’s Records, 1936–1964. LR 3695 21, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Haycock, D. Arthur. Correspondence, 1954–1961. Courtesy of Lynette Haycock Dowdle and Brett D. Dowdle. “Incoming Letters of the Board of Health.” Hansen’s Disease. -

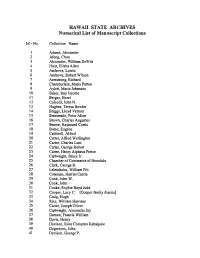

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

Commemorating the Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial

Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial Commemorating the Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th-century in the United States. During this time, several missionary societies were formed. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was organized under Calvinist ecumenical auspices at Bradford, Massachusetts, on the June 29, 1810. The first of the missions of the ABCFM were to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and India, as well as to the Cherokee and Choctaw of the southeast US. In October 1816, the ABCFM established the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, CT, for the instruction of native youth to become missionaries, physicians, surgeons, schoolmasters or interpreters. By 1817, a dozen students, six of them Hawaiians, were training at the Foreign Mission School to become missionaries to teach the Christian faith to people around the world. One of those was ʻŌpūkahaʻia, a young Hawaiian who came to the US in 1809, who was being groomed to be a key figure in a mission to Hawai‘i. ʻŌpūkahaʻia yearned “with great earnestness that he would (return to Hawaiʻi) and preach the Gospel to his poor countrymen.” Unfortunately, ʻŌpūkahaʻia died unexpectedly at Cornwall on February 17, 1818. The life and memoirs of ʻŌpūkahaʻia inspired other missionaries to volunteer to carry his message to the Hawaiian Islands. On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of ABCFM missionaries from the northeast US, set sail on the Thaddeus for the Hawaiian Islands. They first sighted the Islands and arrived at Kawaihae on March 30, 1820, and finally anchored at Kailua-Kona, April 4, 1820. -

Daughters of Hawaiʻi Calabash Cousins

Annual Newsletter 2018 • Volume 41 Issue 1 Daughters of Hawaiʻi Calabash Cousins “...to perpetuate the memory and spirit of old Hawai‘i and of historic facts, and to preserve the nomenclature and correct pronunciation of the Hawaiian language.” The Daughters of Hawaiʻi request the pleasure of Daughters and Calabash Cousins to attend the Annual Meeting on Wednesday, February 21st from 10am until 1:30pm at the Outrigger Canoe Club 10:00 Registration 10:30-11:00 Social 11:00-12:00 Business Meeting 12:00-1:00 Luncheon Buffet 1:00-1:30 Closing Remarks Reservation upon receipt of payment Call (808) 595-6291 or [email protected] RSVP by Feb 16th Cost: $45 Attire: Whites No-Host Bar Eligibility to Vote To vote at the Annual Meeting, a Daughter must be current in her annual dues. The following are three methods for paying dues: 1) By credit card, call (808) 595-6291. 2) By personal check received at 2913 Pali Highway, Honolulu HI 96817-1417 by Feb 15. 3) By cash or check at the Annual Meeting registration (10-10:30am) on February 21. If unable to attend the Annual Meeting, a Daughter may vote via a proxy letter: 1) Identify who will vote on your behalf. If uncertain, you may choose Barbara Nobriga, who serves on the nominating committee and is not seeking office. 2) Designate how you would like your proxy to vote. 3) Sign your letter (typed signature will not be accepted). 4) Your signed letter must be received by February 16, 2017 via post to 2913 Pali Highway, Honolulu HI 96817-1417 or via email to [email protected]. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Mission Stations

Mission Stations The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), based in Boston, was founded in 1810, the first organized missionary society in the US. One hundred years later, the Board was responsible for 102-mission stations and a missionary staff of 600 in India, Ceylon, West Central Africa (Angola), South Africa and Rhodesia, Turkey, China, Japan, Micronesia, Hawaiʻi, the Philippines, North American native American tribes, and the "Papal lands" of Mexico, Spain and Austria. On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of ABCFM missionaries set sail on the Thaddeus to establish the Sandwich Islands Mission (now known as Hawai‘i). Over the course of a little over 40-years (1820- 1863 - the “Missionary Period”), about 180-men and women in twelve Companies served in Hawaiʻi to carry out the mission of the ABCFM in the Hawaiian Islands. One of the earliest efforts of the missionaries, who arrived in 1820, was the identification and selection of important communities (generally near ports and aliʻi residences) as “Stations” for the regional church and school centers across the Hawaiian Islands. As an example, in June 1823, William Ellis joined American Missionaries Asa Thurston, Artemas Bishop and Joseph Goodrich on a tour of the island of Hawaiʻi to investigate suitable sites for mission stations. On O‘ahu, locations at Honolulu (Kawaiahaʻo), Kāne’ohe, Waialua, Waiʻanae and ‘Ewa served as the bases for outreach work on the island. By 1850, eighteen mission stations had been established; six on Hawaiʻi, four on Maui, four on Oʻahu, three on Kauai and one on Molokai. Meeting houses were constructed at the stations, as well as throughout the district. -

Sharks Upon the Land Seth Archer Index More Information Www

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17456-6 — Sharks upon the Land Seth Archer Index More Information Index ABCFM (American Board of ‘anā‘anā (sorcery), 109–10, 171, 172, 220 Commissioners for Foreign Missions), Andrews, Seth, 218 148, 152, 179, 187, 196, 210, 224 animal diseases, 28, 58–60 abortion, 220 annexation by US, 231, 233–34 adoption (hānai), 141, 181, 234 Aotearoa. See New Zealand adultery, 223 Arago, Jacques, 137 afterlife, 170, 200 Armstrong, Clarissa, 210 ahulau (epidemic), 101 Armstrong, Rev. Richard, 197, 207, 209, ‘aiea, 98–99 216, 220, 227 ‘Aikanaka, 187, 211 Auna, 153, 155 aikāne (male attendants), 49–50 ‘awa (kava), 28–29, 80, 81–82, 96, 97, ‘ai kapu (eating taboo), 31, 98–99, 124, 135, 139, 186 127, 129, 139–40, 141, 142, 143 bacterial diseases, 46–47 Albert, Prince, 232 Baldwin, Dwight, 216, 221, 228 alcohol consumption, 115–16, baptism, 131–33, 139, 147, 153, 162, 121, 122, 124, 135, 180, 186, 177–78, 183, 226 189, 228–29 Bayly, William, 44 Alexander I, Tsar of Russia, 95, 124 Beale, William, 195–96 ali‘i (chiefs) Beechey, Capt. Richard, 177 aikāne attendants, 49–50 Bell, Edward, 71, 72–73, 74 consumption, 122–24 Beresford, William, 56, 81 divine kingship, 27, 35 Bible, 167, 168 fatalism, 181, 182–83 Bingham, Hiram, 149, 150, 175, 177, 195 genealogy, 23, 26 Bingham, Sybil, 155, 195 kapu system, 64, 125–26 birth defects, 52 medicine and healing, 109 birth rate, 206, 217, 225, 233 mortality rates, 221 Bishop, Rev. Artemas, 198, 206, 208 relations with Britons, 40, 64 Bishop, Elizabeth Edwards, 159 sexual politics, 87 Blaisdell, Richard Kekuni, 109 Vancouver accounts, 70, 84 Blatchley, Abraham, 196 venereal disease, 49 Blonde (ship), 176 women’s role, 211 Boelen, Capt. -

An Here's What Transpired After Our Visit

Underwritten by U.S. Bureau of Ameri- Hawai'i. B. San Francisco, Sept. 1, 1918. can Ethnology, it provided first "defini- Educ. Stanford University (1940). Visited tive" examination of the ritual and types Hawai'i 1932 with parents, impressed by of dances performed in ancient Hawai'i. Bray troupe, revisited 1937, enrolled 'Hawaii, Some of his translations and point of summer classes University of view eventually were challenged, but 1938. Studied hula under Marguerite there is no other work that offers so much Duane, San Francisco, 1940s, dancing as or is so highly respected by modern kumu amateur in South Seas Club. Moved to bula.Firstpublished, 1909 in limited edi- Hawai'i 1947, continuing study with Bill tion, became rare and generally unavaila- Lincoln studio (several teachers), Alice ble, until 1955 when reprinted in inex- Keawekane, Koochie Kuhns (dancing in pensive paperback, Charles E. Tuttle her group a short while). Worked Rec- Co-pa.ry. Last great work, Pele and ords of Hawaii (\flaikrki record shop), Hf iaka : A Mytb from Hawai'1, published teaching first classes in the store to 1915, Honolulu Star-Bulletin Ltd., told school-aged girls; also Betty Lei Hula Hawai'i's most popular, and best, legend, Studio. Opened own Hula Nani Studio, offering Hawaiian texts and translations 1949, same year took group into NATHANIEL B. EMERSON of more than 300 songs, chants, prayers, Kapi'olani Park hula festival, then into Unfortunatel5 this too entered the Niumalu Hotel. Known for discipline 6c Historian, writer, translator, greatest etc. rare book category, until 1978 when it perfection of "Hawaiian" image-long collector of hula legend and chants. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

CHRONOLOGY of HILO BOARDING SCHOOL HILO, HAWAII Christina R. N. Lothian 1985

CHRONOLOGY OF HILO BOARDING SCHOOL HILO, HAWAII Christina R. N. Lothian 1985 CONTENTS Early Missionary Days 3 Starting the Mission in Hila 4 The Common Schools 6 Hila as Seen by Sarah J. Lyman 8 Hila Boarding School 12 Rev. J. Makaimoku Naeole 25 Rev. William Brewster Oleson 25 Rev. A. W. Burt 27 Mr. and Mrs. Willard Terry 28 Levi Chamberlain Lyman 29 G. Shannon Walker, Villags Dragoo, Ernest A Lilley, John H. Beukama 34 Hila Branch University of Hawaii at Hila 35 Hila Boys Club 36 Bibliography Pictures EARLY MISSIONARY DAYS The Missionaries who carne to Hawaii in the First Company as in v subsiquent Companies, were sent by the American Board of Commissioners ~ for Foreign Missions, who were headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts. (Hence forth the American Board for Foreign Missions will be ABCFM.) The First Company arrived in Hawaiian waters in 1820 not knowing that Kamehameha I had died in 1819 and with him the Kapu system as he knew it. Change was taking place even as they were still at sea. Their ~ first port was Kailua, Kona where they recieved permission for some of the party to stay and the rest sailed for the port of Honolulu. This Chronology will not include all of the landmark information about the Missionaries because it is about the Hilo Board- ing School and the people involved with it. 3 STARTING THE MISSION IN HILO, ISLAND OF HAWAII 1822 In April Rev. William Ellis and a London Mission Society deligation from Tahiti on their way to the Marquasas went no farther than Hawaii.