Seatimes May 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts Books & Ephemera

Arts 5. Dom Gusman vole les Confitures chez le Cardinal, dont il est reconnu. Tome 2, 1. Adoration Des Mages. Tableau peint Chap. 6. par Eugene Deveria pour l'Eglise de St. Le Mesle inv. Dupin Sculp. A Paris chez Dupin rue St. Jacques A.P.D.R. [n.d., c.1730.] Leonard de Fougeres. Engraving, 320 x 375mm. 12½ x 14¾". Slightly soiled A. Deveria. Lith. de Lemercier. [n.d., c.1840.] and stained. £160 Lithograph, sheet 285 x 210mm. 11¼ x 8¼". Lightly Illustration of a scene from Dom Juan or The Feast foxed. £80 with the Statue (Dom Juan ou le Festin de pierre), a The Adoration of the Magi is the name traditionally play by Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, known by his stage given to the representation in Christian art of the three name Molière (1622 - 1673). It is based on the kings laying gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh legendary fictional libertine Don Juan. before the infant Jesus, and worshiping Him. This Engraved and published in Paris by Pierre Dupin interpretation by Eugene Deveria (French, 1808 - (c.1690 - c.1751). 1865). From the Capper Album. Plate to 'Revue des Peintres' by his brother Achille Stock: 10988 Devéria (1800 - 1857). As well as a painter and lithographer, Deveria was a stained-glass designer. Numbered 'Pl 1.' upper right. Books & Ephemera Stock: 11084 6. Publicola's Postscript to the People of 2. Vauxhall Garden. England. ... If you suppose that Rowlandson & Pugin delt. et sculpt. J. Bluck, aquat. Buonaparte will not attempt Invasion, you London Pub. Octr. 1st. 1809, at R. -

Summer 2018 No

THE WREN Summer 2018 No. 392 Summer 2018 The Association of Wrens (Women of The Royal Naval Services) PATRON: Her Royal Highness The Princess Royal PRESIDENT: Cmdt. Anthea Larken CBE VICE PRESIDENTS: Mrs Marion Greenway Mrs Janet Crabtree Mrs Anne Trigg Mrs Pat Farrington Mrs Elsie Baring RD Mrs Beryl Watt Mrs Patricia Wall Mrs Julia Clark Mrs Marjorie Imlah OBE JP Miss Rosie Wilson OBE Miss Julia Simpson BSc CEng MBCS Mrs Mary Hawthornthwaite Miss Eleanor Patrick Mrs Carol Gibbon CHAIRMAN: Miss Jill Stellingworth VICE-CHAIRMAN: Mrs Linda Mitchell HON. TREASURER: Mrs Rita Hoddinott EDITORIAL TEAM OF THE WREN: Mrs Georgina Tuckett Mrs Rita Hoddinott PUBLIC RELATIONS OFFICER: Mrs Celia Saywell MBE ADMINISTRATORS: Mrs Katharine Lovegrove Mrs Lin Burton TRUSTEES: Mrs Janice Abbots Mrs Lisa Snowden Mrs Kathy Carter Mrs Vicki Taylor Mrs Sue Dunster Mrs Georgina Tuckett Mrs Karen Elliot Mrs Fay Watson Mrs Barbara McGregor Subscriptions: Membership renewal for 2019/20 payable by 1 April 2019 Annual membership for UK members £12.50 or 10 years for £100 Annual membership for overseas members £15.50 or 10 years for £120 All correspondence for the Association of Wrens should be sent to: Association of Wrens, Room 215, Semaphore Tower (PP 70) HM Naval Base, Portsmouth PO1 3LT Tel: 02392 725141 email: [email protected] If a reply is required, please enclose a stamped addressed envelope The contents of THE WREN are strictly copyright and all rights are expressly reserved. The views expressed herein are not necessarily the views of the Editorial Team or the Association and accordingly no responsibility for these will be accepted. -

The Marine Sale Marine The

Wednesday 18 April 2018 Wednesday THE MARINE SALE THE MARINE SALE | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 18 April 2018 24653 Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Co-Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Gordon McFarlan, Andrew McKenzie, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Harvey Cammell Deputy Chairman, Simon Mitchell, Jeff Muse, Mike Neill, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Antony Bennett, Matthew Bradbury, Charlie O’Brien, Giles Peppiatt, India Phillips, Matthew Girling CEO, Lucinda Bredin, Simon Cottle, Andrew Currie, Peter Rees, John Sandon, Tim Schofield, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Patrick Meade Group Vice Chairman, Jean Ghika, Charles Graham-Campbell, Veronique Scorer, Robert Smith, James Stratton, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Jon Baddeley, Rupert Banner, Geoffrey Davies, Matthew Haley, Richard Harvey, Robin Hereford, Ralph Taylor, Charlie Thomas, David Williams, Jonathan Fairhurst, Asaph Hyman, James Knight, David Johnson, Charles Lanning, Grant Macdougall Michael Wynell-Mayow, Suzannah Yip. Caroline Oliphant, Shahin Virani, Edward Wilkinson, Leslie Wright. THE MARINE SALE Wednesday 18 April 2018 at 2pm Knightsbridge, London BONHAMS ENQUIRIES Please see page 2 for bidder IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street information including after-sale In February 2014 the United Knightsbridge Pictures collection and shipment States Government announced London SW7 1HH Leo Webster the intention to ban the import www.bonhams.com +44 (0) 20 7393 3865 Please see back of catalogue of any ivory into the USA. Lots [email protected] for important notice to bidders containing ivory are indicated by VIEWING the symbol Ф printed beside the Sunday 15 April Veronique Scorer ILLUSTRATIONS Lot number in this catalogue. -

Of Deaths in Service of Royal Naval Medical, Dental, Queen Alexandra's Royal Naval Nursing Service and Sick Berth Staff

Index of Deaths in Service of Royal Naval Medical, Dental, Queen Alexandra’s Royal Naval Nursing Service and Sick Berth Staff World War II Researched and collated by Eric C Birbeck MVO and Peter J Derby - Haslar Heritage Group. Ranks and Rate abbreviations can be found at the end of this document Name Rank / Off No 1 Date Ship, (Pennant No), Type, Reason for loss and other comrades lost and Rate burial / memorial details (where known). Abel CA SBA SR8625 02/10/1942 HMS Tamar. Hong Kong Naval Base. Drowned, POW (along with many other medical shipmates) onboard SS Lisbon Maru sunk by US Submarine Grouper. 2 Panel 71, Column 2, Plymouth Naval Memorial, Devon, UK. 1 Officers’ official numbers are not shown as they were not recorded on the original documents researched. Where found, notes on awards and medals have been added. 2 Lisbon Maru was a Japanese freighter which was used as a troopship and prisoner-of-war transport between China and Japan. When she was sunk by USS Grouper (SS- 214) on 1 October 1942, she was carrying, in addition to Japanese Army personnel, almost 2,000 British prisoners of war captured after the fall of Hong Kong in December Name Rank / Off No 1 Date Ship, (Pennant No), Type, Reason for loss and other comrades lost and Rate burial / memorial details (where known). Abraham J LSBA M54850 11/03/1942 HMS Naiad (93). Dido-class destroyer. Sunk by U-565 south of Crete. Panel 71, Column 2, Plymouth Naval Memorial, Devon, UK. Abrahams TH LSBA M49905 26/02/1942 HMS Sultan. -

From the Early Settlements to Reconstruction

The Laird Rams: Warships in Transition 1862-1885 Submitted by Andrew Ramsey English, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Maritime History, April 2016. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) Andrew Ramsey English (signed electronically) 1 ABSTRACT The Laird rams, built from 1862-1865, reflected concepts of naval power in transition from the broadside of multiple guns, to the rotating turret with only a few very heavy pieces of ordnance. These two ironclads were experiments built around the two new offensive concepts for armoured warships at that time: the ram and the turret. These sister armourclads were a collection of innovative designs and compromises packed into smaller spaces. A result of the design leap forward was they suffered from too much, too soon, in too limited a hull area. The turret ships were designed and built rapidly for a Confederate Navy desperate for effective warships. As a result of this urgency, the pair of twin turreted armoured rams began as experimental warships and continued in that mode for the next thirty five years. They were armoured ships built in secrecy, then floated on the Mersey under the gaze of international scrutiny and suddenly purchased by Britain to avoid a war with the United States. -

Alphabetical List the Following List Gives the Names of Everyone Featured in the Lord Ashcroft Gallery: Extraordinary Heroes in Alphabetical Order of Their Surnames

Alphabetical list The following list gives the names of everyone featured in the Lord Ashcroft Gallery: Extraordinary Heroes in alphabetical order of their surnames. Alongside each name is given: – The area where that person can be found – The year in which their VC or GC was earned – The country where the VC or GC action took place – The basic military unit in which the person was serving at the time Name of recipient Area Year Country Regiment A Abdul Hafiz VC Aggression 1944 India 9th Jat Infantry Ackroyd, Harold, VC Sacrifice 1917 Belgium Royal Army Medical Corps Agansing Rai, VC Aggression 1944 India 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles Agar, Augustus, VC Leadership 1919 Russia HM Coastal Motor Boat 4 Alderson, Thomas, GC Skill 1940 United Kingdom ARP Rescue Parties Alexander, Ernest, VC Skill 1914 Belgium Royal Field Artillery Algie, Wallace, VC Aggression 1918 France 20th Canadian Battalion Ali Haidar, VC Initiative 1945 Italy 13th Frontier Force Rifles Anderson, William, VC Leadership 1918 France Highland Light Infantry Andrews, Henry, VC Sacrifice 1919 India Indian Medical Service Annand, Richard, VC Skill 1940 Belgium Durham Light Infantry Armitage, Selby, GC Skill 1940 United Kingdom Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Ashburnham, Doreen, GC Endurance 1916 Canada Civilian B Babington, John, GC Boldness 1940 United Kingdom Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Badlu Singh, VC Initiative 1918 Palestine 29th Lancers (Deccan Horse) Baldwin, Geoffrey, GC Skill 1942 United Kingdom Factory Manager Bamford, Jack, GC Sacrifice 1952 United Kingdom Civilian Barefoot, -

The Story of George Hunt & the ULTOR

DIVING STATIONS THE STORY OF CAPTAIN GEORGE HUNT DSO* DSC* RN, ONE OF THE MOST SUCCESSFUL ALLIED SUBMARINE CAPTAINS IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR PETER DORNAN x Pen & Sword MARITIME First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Pen & Sword Maritime An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd 47 Church Street Barnsley South Yorkshire S702AS Copyright © Peter Dornan 2010 ISBN 978 1 84884321 9 The right of Peter Dornan to be- identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writiilg. Typeset by Acredula Printed and bound in England By the MPG Books Group Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing. For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED 47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................... -

Autumn 07 Cover

23 Charles Miller Ltd Maritime and Scientific Models, Charles Miller Ltd Instruments & Art London Tuesday 30th April 2019 London Tuesday 30th April 2019 London Tuesday Charles Miller Ltd 6 Imperial Studios, 3/11 Imperial Road, London, SW6 2AG Tel: +44 (0) 207 806 5530 • Fax: +44 (0) 207 806 5531 • Email: [email protected] www.charlesmillerltd.com BIKES Auction Enquiries and Information Sale Number: 023 Bidding at Auction: Code name: HESPERUS There are a number of ways to bid at auction: BIKES Enquiries Consultant + In person, registration required Charles Miller Michael Naxton + Absentee bid, see form on page 126 Sara Sturgess + Telephone, where available, must be booked by 12noon on 28 Charles Miller Ltd Monday 29th April. DoubleTree by 6 Imperial Studios, + Online, via third-party websites: 391 3/11 Imperial Road 28 Hilton hotel LONDON SW6 2AG 391 Catalogues and Online Bidding: Telephone: +44 (0) 207 806 5530 Printed catalogues available in person or by Facsimile: +44 (0) 207 806 5531 post at £20 (plus postage) Sale Venue and Main View: Office, Post-Sale Collection and Large Object View: Email: [email protected] 25 Blythe Road, London W14 0PD 6 Imperial Studios, London SW6 2AG www.charlesmillerltd.com The Auction Room: FREE OF CHARGE Payment Please ensure you make arrangements to bid Payment is due in sterling at the conclusion of the sale and before purchases can be released. Our preferred method of Live Auctioneers: 3% surcharge payment is by electronic bank transfer and amounts over £2,000 must be made by this method. in sufficient time before the sale. -

Model Ship Book 9Th Issue

in 1/1200 & 1/1250 scale Issue 10 (June 2016) How it all began CONTENTS FOREWORD 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Aim and Acknowledgements 3 The UK Scene 3 Overseas 5 Collecting 5 Sources of Information 5 Warship Camouflage 6 Lists of Manufacturers 6 CHAPTER 2 UNITED KINGDOM MANUFACTURERS 9 ATLAS EDITIONS 9 BASSETT-LOWKE 9 BROADWATER 9 CAP AERO 10 CLYDESIDE 10 COASTLINES 11 CONNOLLY 11 CRUISE LINE MODELS 11 DEEP “C”/ATHELSTAN 11 ENSIGN 12 FERRY SMALL SHIPS 12 FIGUREHEAD 12 FLEETLINE 12 GORKY 13 GRAND FLEET MINIATURES 13 GWYLAN 14 HORNBY MINIC (ROVEX) 14 KS MODELSHIPS 14 LANGTON MINIATURES 15 LEICESTER MICROMODELS 15 LEN JORDAN MODELS 15 LIMITED EDITIONS 15 LLYN 16 LOFTLINES 16 MARINE ARTISTS MODELS 17 MB/HIGHWORTH MODELS 17 MOUNTFORD MODELS 17 NAVWAR 18 NELSON 19 NKC SHIPS 19 OCEANIC 19 PEDESTAL 20 PIER HEAD MODELS 20 SANTA ROSA SHIPS 20 SEA-VEE 22 SKYTREX/MERCATOR (TRITON 1250) 23 Mercator (and Atlantic) 26 SOLENT MODEL SHIPS 30 TRIANG 30 TRIANG MINIC SHIPS LIMITED 31 WASS-LINE 33 (i) WMS (Wirral Miniature Ships) 33 CHAPTER 3 CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURERS 35 Major Manufacturers 35 ALBATROS 35 ARGONAUT 35 RN Models in the Original Series 36 USN Models in the Original Series 37 ARGOS 37 CARAT & CSC 38 CM 39 DELPHIN 42 “G” (the models of Georg Grzybowski) 44 HAI 46 HANSA 48 KLABAUTERMANN 51 NAVIS/NEPTUN (and Copy) 52 NAVIS WARSHIPS 53 Austro-Hungarian Navy 53 Brazilian Navy 53 Royal Navy 53 French Navy 53 Italian Navy 54 Imperial Japanese Navy 54 Imperial German Navy (& Reichmarine) 54 Russian Navy 55 Swedish Navy 55 United States Navy 55 NEPTUN -

RCHS Chronology of Modern Transport in the British Isles 1945

RCHS Chronology of Modern Transport in the British Isles 1945–2015 Introduction This chronology is intended to set out some of the more significant events in the recent history of transport and communication, with particular reference to public transport, in the British Isles since the end of 1944. It cannot hope to cover the closure or opening of every branch railway or canal, the sale of every bus company, nor the coming and going of every pertinent office holder. The hope is that it does contain details of the principal legislative and organisational changes affecting transport – in particular the shifts between private and public ownership which have characterised the industry within this period – together with some notable ‘firsts’, ‘lasts’ and other significant events, especially those which exhibit trends. A very few overseas events are included (in italics), either because they had a British relationship, or for comparative purposes. Conventions Dates are, where appropriate, the first or last occasion on which an ordinary member of the public could make full use of the facility: official and partial openings on different dates are in general confined to parentheses; and ‘closed with effect from’ (wef) dates are quoted only where the actual last day of service has not been certainly established. Dates assigned to statutes are those of assent unless stated otherwise. ‘First’, ‘last’ or similar qualifiers mean ‘in Britain’ unless otherwise indicated. ‘Commercial’ is used, rather loosely, as a qualifier to exclude experimental, enthusiast, heritage, leisure or similar operations. Forms of name are those in use at the date of the event. -

The Myth of British Naval Intervention in the American Civil War Howard J

Page 1 of 13 Iron Lion or Paper Tiger? The Myth of British Naval Intervention in the American Civil War Howard J. Fuller I When it comes to the thought-provoking subject of foreign intervention in the Civil War, especially by Great Britain, much of the history has been more propaganda than proper research; fiction over fact. In 1961, Kenneth Bourne offered up a fascinating article on “British Preparations for War with the North, 1861–1862” for the English Historical Review. While focusing largely on the military defense of Canada during the Trent Affair, Bourne also stressed that Britain’s “position at sea was by no means so bad,” though he potentially confused the twentieth-century reader by referring to “battleships” rather than (steam- powered, sail, and screw-propelled) wooden ships-of-the-line, for example. This blurred the important technological changes that were certainly in play by 1861—and not necessarily in Britain’s favor. The Great Lakes the British considered to be largely a write-off as there were no facilities in place for building ironclads, much less floating wooden gunboats up frozen rivers and canals during the long winter season. American commerce and industrialization in the Midwest, on the other hand, had led to booming local ports like Chicago, Detroit, Toledo, and Cleveland—all facilitated by new railroads. Of course, Parliament had not seen to maximizing the defense of the British Empire’s many frontiers and outposts over the years. If anything, the legendary reputation of the Royal Navy continually undermined that imperative. That left the onus of any real war against the United States to Britain’s ability to lay down a naval offensive. -

The Semaphore Circular

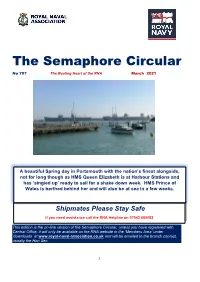

The Semaphore Circular No 707 The Beating Heart of the RNA March 2021 A beautiful Spring day in Portsmouth with the nation’s finest alongside, not for long though as HMS Queen Elizabeth is at Harbour Stations and has ‘singled up’ ready to sail for a shake down week. HMS Prince of Wales is berthed behind her and will also be at sea in a few weeks. Shipmates Please Stay Safe If you need assistance call the RNA Helpline on 07542 680082 This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Central Office Contacts General Secretary 023 9272 2983 [email protected] Financial Manager 023 9272 3823 [email protected] Finance Assistant 023 9272 3823 [email protected] Communications Manager 07860 705712 [email protected] Digital Communications [email protected] Membership Support 07542 680082 [email protected] Manager Membership Support 023 92723747 [email protected] Assistant Welfare Programme 07591 829416 [email protected] Manager Project Semaphore [email protected] Operations Officer 07889 761934 [email protected] Admin 023 9272 3747 [email protected] National Advisors National Branch Retention [email protected] and Recruiting Advisor National Welfare Advisor [email protected] National Rules and Bye- [email protected] Laws Advisor National Ceremonial [email protected] Advisor PLEASE NOTE DURING THE CURRENT RESTRICTIONS CENTRAL OFFICE IS CLOSED.