Cartography in Children's Literature. PUB DATE 96 NOTE 4P.; In: Sustaining the Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC 1 Dear Candidate, in Preparation for the Graphic Design & Illu

Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC Dear Candidate, In preparation for the Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC certification exam, we’ve put together a set of practice materials and example exam items for you to review. What you’ll find in this packet are: • Topic areas and objectives for the exam. • Links to practice tutorials and files. • Practice exam items. We’ve assembled excerpted material from the Adobe Illustrator CC Learn and Support page, and the Visual Design curriculum to highlight a few of the more challenging techniques covered on the exam. You can work through these technical guides and with the provided image files (provided separately). Additionally, we’ve included the certification objectives so that you are aware of the elements that are covered on the exam. Finally, we’ve included practice exam items to give you a feel for some of the items. These materials are meant to help you familiarize yourself with the areas of the exam so are not comprehensive across all the objectives. Thank you, Adobe Education Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Photoshop and Creative Cloud are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems 1 Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. © 2017 Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC Adobe Certified Associate in Graphic Design & Illustration Using Adobe Illustrator CC (2015) Exam Structure The following lists the topic areas for the exam: • Setting project requirements • Understanding Digital Graphics and Illustrations • Understanding Adobe Illustrator • Creating Digital Graphics and Illustrations Using Adobe Illustrator • Archive, Export, and Publish Graphics Using Adobe Illustrator Number of Questions and Time • 40 questions • 50 minutes Exam Objectives Domain 1.0 Setting Project Requirements 1.1 Identify the purpose, audience, and audience needs for preparing graphics and illustrations. -

Realistic Modeling and Rendering of Plant Ecosystems

Realistic modeling and rendering of plant ecosystems Oliver Deussen1 Pat Hanrahan2 Bernd Lintermann3 RadomÂõr MechÏ 4 Matt Pharr2 Przemyslaw Prusinkiewicz4 1 Otto-von-Guericke University of Magdeburg 2 Stanford University 3 The ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe 4 The University of Calgary Abstract grasslands, human-made environments, for instance parks and gar- dens, and intermediate environments, such as lands recolonized by Modeling and rendering of natural scenes with thousands of plants vegetation after forest ®res or logging. Models of these ecosystems poses a number of problems. The terrain must be modeled and plants have a wide range of existing and potential applications, including must be distributed throughout it in a realistic manner, re¯ecting the computer-assisted landscape and garden design, prediction and vi- interactions of plants with each other and with their environment. sualization of the effects of logging on the landscape, visualization Geometric models of individual plants, consistent with their po- of models of ecosystems for research and educational purposes, sitions within the ecosystem, must be synthesized to populate the and synthesis of scenes for computer animations, drive and ¯ight scene. The scene, which may consist of billions of primitives, must simulators, games, and computer art. be rendered ef®ciently while incorporating the subtleties of lighting Beautiful images of forests and meadows were created as early in a natural environment. as 1985 by Reeves and Blau [50] and featured in the computer We have developed a system built around a pipeline of tools that animation The Adventures of Andre and Wally B. [34]. Reeves and address these tasks. -

617.727.5944 2.7 Labeling a Picture Or a Diagram

BPS Curriculum Framework > Informational/Explanatory Text > Grade 2 > Drafting and Revising > Labeling a picture or diagram 2.7 Labeling a picture or a Connection : We have been noticing the beautiful pictures and helpful diagram diagrams in our mentor text for “all-about” books. We have even added pictures and diagrams to our own writing to really give our readers a better idea of what our subject looks like, but there is still one more thing we need to think about. We need to be sure our readers understand what they are looking at. Learning Objective: Students will label pictures and Teaching : Labeling our pictures gives our readers a better diagrams from the outdoor understanding of what they are looking at. Our labels help the reader classroom know exactly what they are seeing. It may tell the time of the year, the location, the size, or the specific parts of the subject they are looking at. Let’s look at The “Saddle Up!” Section in the “Kids book of Horses” and see how the author has used labels to teach us the parts of a Mentor Texts: “Volcanoes”; saddle. “Bears, Bears, Bears”; “Try It Think about something in the classroom and tell your partner “Apples”; “The Pumpkin what you might have to label if you were going to illustrate this object. Book”; “ The Kids Horse Book ”, Share out with class. Sylvia Funston Instructions to students for Independent Outdoor Writing : 1. Today, when we go out to the outdoor classroom we are going to choose an object to illustrate. It can be from our classroom list or anything else you see outside (at boat in the harbor, a truck or car going by, a small animal scampering away, or items on the playground: a slide or climbing frame. -

Visualization in Multiobjective Optimization

Final version Visualization in Multiobjective Optimization Bogdan Filipič Tea Tušar Tutorial slides are available at CEC Tutorial, Donostia - San Sebastián, June 5, 2017 http://dis.ijs.si/tea/research.htm Computational Intelligence Group Department of Intelligent Systems Jožef Stefan Institute Ljubljana, Slovenia 2 Contents Introduction A taxonomy of visualization methods Visualizing single approximation sets Introduction Visualizing repeated approximation sets Summary References 3 Introduction Introduction Multiobjective optimization problem Visualization in multiobjective optimization Minimize Useful for different purposes [14] f: X ! F • Analysis of solutions and solution sets f:(x ;:::; x ) 7! (f (x ;:::; x );:::; f (x ;:::; x )) 1 n 1 1 n m 1 n • Decision support in interactive optimization • Analysis of algorithm performance • X is an n-dimensional decision space ⊆ Rm ≥ • F is an m-dimensional objective space (m 2) Visualizing solution sets in the decision space • Problem-specific ! Conflicting objectives a set of optimal solutions • If X ⊆ Rm, any method for visualizing multidimensional • Pareto set in the decision space solutions can be used • Pareto front in the objective space • Not the focus of this tutorial 4 5 Introduction Introduction Visualization can be hard even in 2-D Stochastic optimization algorithms Visualizing solution sets in the objective space • Single run ! single approximation set • Interested in sets of mutually nondominated solutions called ! approximation sets • Multiple runs multiple approximation sets • Different -

Inviwo — a Visualization System with Usage Abstraction Levels

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VISUALIZATION AND COMPUTER GRAPHICS, VOL X, NO. Y, MAY 2019 1 Inviwo — A Visualization System with Usage Abstraction Levels Daniel Jonsson,¨ Peter Steneteg, Erik Sunden,´ Rickard Englund, Sathish Kottravel, Martin Falk, Member, IEEE, Anders Ynnerman, Ingrid Hotz, and Timo Ropinski Member, IEEE, Abstract—The complexity of today’s visualization applications demands specific visualization systems tailored for the development of these applications. Frequently, such systems utilize levels of abstraction to improve the application development process, for instance by providing a data flow network editor. Unfortunately, these abstractions result in several issues, which need to be circumvented through an abstraction-centered system design. Often, a high level of abstraction hides low level details, which makes it difficult to directly access the underlying computing platform, which would be important to achieve an optimal performance. Therefore, we propose a layer structure developed for modern and sustainable visualization systems allowing developers to interact with all contained abstraction levels. We refer to this interaction capabilities as usage abstraction levels, since we target application developers with various levels of experience. We formulate the requirements for such a system, derive the desired architecture, and present how the concepts have been exemplary realized within the Inviwo visualization system. Furthermore, we address several specific challenges that arise during the realization of such a layered architecture, such as communication between different computing platforms, performance centered encapsulation, as well as layer-independent development by supporting cross layer documentation and debugging capabilities. Index Terms—Visualization systems, data visualization, visual analytics, data analysis, computer graphics, image processing. F 1 INTRODUCTION The field of visualization is maturing, and a shift can be employing different layers of abstraction. -

A Very Simple Approach for 3-D to 2-D Mapping

Image Processing & Communications, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 75-82 75 A VERY SIMPLE APPROACH FOR 3-D TO 2-D MAPPING SANDIPAN DEY (1), AJITH ABRAHAM (2),SUGATA SANYAL (3) (1) Anshin Soft ware Pvt. Ltd. INFINITY, Tower - II, 10th Floor, Plot No.- 43. Block - GP, Salt Lake Electronics Complex, Sector - V, Kolkata - 700091 email: [email protected] (2) IITA Professorship Program, School of Computer Science, Yonsei University, 134 Shinchon-dong, Sudaemoon-ku, Seoul 120-749, Republic of Korea email: [email protected] (3) School of Technology & Computer Science Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai - 400005, INDIA email: [email protected] Abstract. libraries with any kind of system is often a tough trial. This article presents a very simple method of Many times we need to plot 3-D functions e.g., in mapping from 3-D to 2-D, that is free from any com- many scientific experiments. To plot this 3-D func- plex pre-operation, also it will work with any graph- tions on 2-D screen it requires some kind of map- ics system where we have some primitive 2-D graph- ping. Though OpenGL, DirectX etc 3-D rendering ics function. Also we discuss the inverse transform libraries have made this job very simple, still these and how to do basic computer graphics transforma- libraries come with many complex pre-operations tions using our coordinate mapping system. that are simply not intended, also to integrate these 76 S. Dey, A. Abraham, S. Sanyal 1 Introduction 2 Proposed approach We have a pictorial representation (Fig.1) of our 3-D to 2-D mapping system: We have a function f : R2 → R, and our intention is to draw the function in 2-D plane. -

Guns, More Crime Author(S): Mark Duggan Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol

More Guns, More Crime Author(s): Mark Duggan Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 109, No. 5 (October 2001), pp. 1086-1114 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/322833 Accessed: 03-04-2018 19:37 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Political Economy This content downloaded from 153.90.149.52 on Tue, 03 Apr 2018 19:37:56 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms More Guns, More Crime Mark Duggan University of Chicago and National Bureau of Economic Research This paper examines the relationship between gun ownership and crime. Previous research has suffered from a lack of reliable data on gun ownership. I exploit a unique data set to reliably estimate annual rates of gun ownership at both the state and the county levels during the past two decades. My findings demonstrate that changes in gun ownership are significantly positively related to changes in the hom- icide rate, with this relationship driven almost entirely by an impact of gun ownership on murders in which a gun is used. -

Graphics Formats and Tools

Graphics formats and tools Images à recevoir Stand DRG The different types of graphics format Graphics formats can be classified broadly in 3 different groups -Vector - Raster (or bitmap) - Page description language (PDL) Graphics formats and tools 2 Vector formats In a vector format (revisable) a line is defined by 2 points, the text can be edited Graphics formats and tools 3 Raster (bitmap) format A raster (bitmap) format is like a photograph; the number of dots/cm defines the quality of the drawing Graphics formats and tools 4 Page description language (PDL) formats A page description language is a programming language that describes the appearance of a printed page at a higher level than an actual output bitmap Adobe’s PostScript (.ps), Encapsulated PostScript (.eps) and Portable Document Format (.pdf) are some of the best known page description languages Encapsulated PostScript (.eps) is commonly used for graphics It can contain both unstructured vector information as well as raster (bitmap) data Since it comprises a mixture of data, its quality and usability are variable Graphics formats and tools 5 Background Since the invention of computing, or more precisely since the creation of computer-assisted drawing (CAD), two main professions have evolved - Desktop publishing (DTP) developed principally on Macintosh - Computer-assisted drawing or design (CAD) developed principally on IBM (International Business Machines) Graphics formats and tools 6 Use of DTP applications Used greatly in the fields of marketing, journalism and industrial design, DTP applications fulfil the needs of various professions - from sketches and mock-ups to fashion design - interior design - coachwork (body work) design - web page design -etc. -

The New Plot to Hijack GIS and Mapping

The New Plot to Hijack GIS and Mapping A bill recently introduced in the U.S. Senate could effectively exclude everyone but licensed architects, engineers, and surveyors from federal government contracts for GIS and mapping services of all kinds – not just those services traditionally provided by surveyors. The Geospatial Data Act (GDA) of 2017 (S.1253) would set up a system of exclusionary procurement that would prevent most companies and organizations in the dynamic and rapidly growing GIS and mapping sector from receiving federal contracts for a very-wide range of activities, including GPS field data collection, GIS, internet mapping, geospatial analysis, location based services, remote sensing, academic research involving maps, and digital or manual map making or cartography of almost any type. Not only would this bill limit competition, innovation and free-market approaches for a crucial high-growth information technology (IT) sector of the U.S. economy, it also would cripple the current vibrant GIS industry and damage U.S. geographic information science, research capacity, and competitiveness. The proposed bill would also shackle government agencies, all of which depend upon the productivity, talent, scientific and technical skills, and the creativity and innovation that characterize the vast majority of the existing GIS and mapping workforce. The GDA bill focuses on a 1972 federal procurement law called the Brooks Act that reasonably limits federal contracts for specific, traditional architectural and engineering services to licensed A&E firms. We have no problem with that. However, if S.1253 were enacted, the purpose of the Brooks Act would be radically altered and its scope dramatically expanded by also including all mapping and GIS services as “A&E services” which would henceforth would be required to be procured under the exclusionary Brooks Act (accessible only to A&E firms) to the great detriment of the huge existing GIS IT sector and all other related companies and organizations which have long been engaged in cutting-edge GIS and mapping. -

Basic Science: Understanding Numbers

Document name: How to use infogr.am Document date: 2015 Copyright information: Content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence OpenLearn Study Unit: BASIC SCIENCE: UNDERSTANDING NUMBERS OpenLearn url: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/science-maths-technology/basic-science-understanding-numbers/content-section-overview Basic Science: Understanding Numbers Simon Kelly www.open.edu/openlearn 1 Basic Science: Understanding Numbers A guide to using infogr.am Infographics are friendly looking images and graphs which convey important information. In the past an infographic was the result of a long and painful process between designers and statisticians involving numerous meetings, data management and testing of designs and colour schemes. Nowadays they are much simpler to create. In fact, the company infogr.am has created a website that simplifies this process so that anyone can do it. The guidance below outlines a few simple instructions on how to use infogr.am to create the types of graphs discussed in this course. We will be using the data from the ‘Rainfall data PDF’. You should download the PDF before you start. Remember, you do not need to plot all the graph types or all the data. Simply pick two countries and compare their rainfall. This is a basic guide to Infogr.am; the site can do much more than what we describe below, so have a play and see what you find out! 1. Go to https://infogr.am/. 2. Select ‘Sign up now’ and create a username, enter your email address and choose a password (if you prefer, you can use your Facebook, Twitter or Google+ account to connect and log in). -

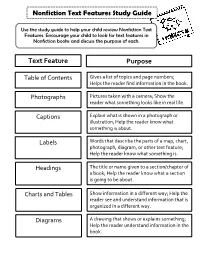

Nonfiction Text Features Study Guide Text Feature Purpose

Nonfiction Text Features Study Guide Use the study guide to help your child review Nonfiction Text Features. Encourage your child to look for text features in Nonfiction books and discuss the purpose of each. Text Feature Purpose Gives a list of topics and page numbers; Table of Contents Helps the reader find information in the book. Photographs Pictures taken with a camera; Show the reader what something looks like in real life. Captions Explain what is shown in a photograph or illustration; Help the reader know what something is about. Labels Words that describe the parts of a map, chart, photograph, diagram, or other text feature; Help the reader know what something is. Headings The title or name given to a section/chapter of a book; Help the reader know what a section is going to be about. Charts and Tables Show information in a different way; Help the reader see and understand information that is organized in a different way. Diagrams A drawing that shows or explains something; Help the reader understand information in the book. Text Feature Purpose Textboxes A box or some other shape that contains text; Show the reader that information is important or interesting. A picture of what something looks like on the Cutaways inside or from another point of view; Help the reader see all parts of something. Types of Print Print can be bold, different colors, fonts, and sizes; Show the reader that something is important or interesting. Close Ups Photographs that have been zoomed in or enlarged to help the reader see something better. -

Illustration Degree Offered: Bachelor of Fine Arts

Illustration Degree Offered: Bachelor of Fine Arts Minors Offered: • Art • Art History • Graphic Design • Illustration • Painting • Sculpture • Theatre Arts The BFA in Illustration focuses on developing drawing skills and their application in a professional en vironment, including editorial illustration, children's book illustration, web-site development, and character design for animation. Illustration at Daemen: • Demonstrate a high level of accomplishment with materials related to the graphic arts. • Visually present a narrative voice through individual compositions or series. • Work within a variety of media to explore editorial or sequential imagery. • Develop an editorial voice to support campaigns, storylines, or public initiatives. Illustration Emphasis: The BFA in Illustration at Daemen College combines the creative process of a fine artist with the problem solving techniques and communication skills of a commercial designer. Students are taught to brainstorm solutions, generate new ideas, and explore the materials and techniques best suited to present an idea. By graduation, the Illustration student will have ex perience in editorial, sequential, computer, packaging and storyboard illustration. Illustration studio courses are supported by substantive drawing instruction, as well as fundamental graphic design con cepts. The program's focus on exploration and process prepares students to develop a portfolio to successfully acquire freelance illustration work, or a full-time position in the publishing or digital communications industry. Faculty: The Illustration faculty work in a variety of professional situations by providing illustrations to magazines, poster cam paigns, and websites. Each maintains a freelance career while simultaneously working with students at Daemen in the development of projects and exhibits. 4103 Suggested Course Sequence for Illustration: 4897 10/16 For more information, contact Christian Brandjes in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at [email protected] or 716-839-8463.