Natural History of Bramble Cay, Torres Strait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between Australia and New Guinea-Ecological and Cultural

Geographical Review of Japan Vol. 59 (Ser. B), No. 2, 69-82, 1986 Between Australia and New Guinea-Ecological and Cultural Diversity in the Torres Strait with Special Reference to the Use of Marine Resources- George OHSHIMA* The region between lowland Papua and the northern tip of the Australian continent presents a fascinating panorama of ecological, cultural and socio-economic diversity. In lowland Papua and on its associated small islands such as Saibai, Boigu and Parama, a combination of coastal forests and muddy shores dominates the scene, whereas the Torres Strait Islands of volcanic and limestone origin, together with raised coral islands and their associated reef systems present a range of island ecosystems scattered over a broad territory some 800km in extent. Coralline habitats extend south wards to the Cape York Peninsula and some parts of Arnhem Land. Coupled with those ecological diversities within a relatively small compass across the Torres Strait, the region has evoked important questions concerning the archaeological and historical dichotomy between Australian hunter-gatherers and Melanesian horticulturalists. This notion is also reflectd in terms of its complex linguistic, ethnic and political composition. In summarizing the present day cultural diversity of the region, at least three major components emerge: hunter-gatherers in the Australian Northern Territory, Australian islanders and tribal Papuans. Historically, these groups have interacted in complex ways and this has resulted in an intricate intermingling of cultures and societies. Such acculturation processes operating over thousands of years make it difficult to isolate meaning ful trends in terms of "core-periphery" components of the individual cultures. -

Net Primary Productivity, Global Climate Change and Biodiversity In

This file is part of the following reference: Fuentes, Mariana Menezes Prata Bezerra (2010) Vulnerability of sea turtles to climate change: a case study within the northern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/11730 Vulnerability of sea turtles to climate change: A case study with the northern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population PhD thesis submitted by Mariana Menezes Prata Bezerra FUENTES (BSc Hons) February 2010 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences James Cook University Townsville, Queensland 4811 Australia “The process of learning is often more important than what is being learned” ii Statement of access I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library, via the Australian Theses Network, or by other means allow access to users in other approved libraries. I understand that as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction access to this thesis. _______________________ ____________________ Signature, Mariana Fuentes Date iii Statement of sources declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ________________________ _____________________ Signature, Mariana Fuentes Date iv Statement of contribution of others Research funding: . -

Land & Sea Management Strategy

LAND & SEA MANAGEMENT STRATEGY for TORRES STRAIT Funded under the Natural Heritage Trust LAND & SEA MANAGEMENT STRATEGY for TORRES STRAIT Torres Strait NRM Reference Group with the assistance of Miya Isherwood, Michelle Pollock, Kate Eden and Steve Jackson November 2005 An initiative funded under the Natural Heritage Trust program of the Australian Government with support from: the Queensland Department of Natural Resources & Mines the Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage and the Torres Strait Regional Authority. Prepared by: Bessen Consulting Services FOREWORD The Torres Strait region is of enormous significance from a land and sea management perspective. It is a geographically and ecologically unique region, which is home to a culturally distinct society, comprised of over 20 different communities, extending from the south-western coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG) to the northern tip of Cape York Peninsula. The Torres Strait is also a very politically complex area, with an international border and a Treaty governance regime that poses unique challenges for coordinating land and sea management initiatives. Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people, both within and outside of the region, have strong and abiding connections with their land and sea country. While formal recognition of this relationship has been achieved through native title and other legal processes, peoples’ aspirations to sustainably manage their land and sea country have been more difficult to realise. The implementation of this Strategy, with funding from the Australian Government’s Natural Heritage Trust initiative, presents us with an opportunity to progress community-based management in our unique region, through identifying the important land and sea assets, issues, information, and potential mechanisms for supporting Torres Strait communities to sustainably manage their natural resources. -

Recovery Plan for the Bramble Cay Melomys Melomys Rubicola Prepared by Peter Latch

Recovery Plan for the Bramble Cay Melomys Melomys rubicola Prepared by Peter Latch Title: Recovery Plan for the Bramble Cay Melomys Melomys rubicola Prepared by: Peter Latch © The State of Queensland, Environmental Protection Agency, 2008 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written knowledge of the Environmental Protection Agency. Inquiries should be addressed to PO Box 15155, CITY EAST QLD 4002. Copies may be obtained from the: Executive Director Conservation Services Environmental Protection Agency PO Box 15155 CITY EAST Qld 4002 Disclaimer: The Australian Government, in partnership with the Environmental Protection Agency facilitates the publication of recovery plans to detail the actions needed for the conservation of threatened native wildlife. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, and may also be constrained by the need to address other conservation priorities. Approved recovery actions may be subject to modification due to changes in knowledge and changes in conservation status. Publication reference: Latch, P. 2008.Recovery Plan for the Bramble Cay Melomys Melomys rubicola. Report to Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Canberra. Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane. 2 Contents Page No. Executive Summary 4 1. General information 5 Conservation status 5 International obligations 5 Affected interests 5 Consultation with Indigenous people 5 Benefits to other species or communities 5 Social and economic impacts 5 2. Biological information 5 Species description 5 Life history and ecology 7 Description of habitat 7 Distribution and habitat critical to the survival of the species 9 3. -

Autonomy Rights in Torres Strait: from Whom, for Whom, for Or Over What?

Autonomy rights in Torres Strait: From whom, for whom, for or over what? W.G. Sanders and W.S. Arthur No. 215/2001 ISSN 1036-1774 ISBN 0 7315 2650 3 Will Sanders is a Fellow and Bill Arthur a Research Fellow at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University. CENTRE FOR ABORIGINAL ECONOMIC POLICY RESEARCH DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 215 iii Table of contents Abbreviations and acronyms ...............................................................................iv Summary .............................................................................................................v Acknowledgments ................................................................................................v Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Calls for autonomy, and existing and proposed governance structures ................ 4 From whom? ....................................................................................................... 8 For whom? .......................................................................................................... 9 For or over what? .............................................................................................. 12 Autonomy, Australian federalism, and regional ethnic diversity: A concluding comment ...................................................................................... 15 Notes................................................................................................................ -

Determination 2016 (No 2)

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Throsby) Determination 2016 (No 2) Disallowable instrument DI2016-211 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989, s 3 (Minister to determine names) 1 Name of instrument This instrument is the Public Place Names (Throsby) Determination 2016 (No 2). 2 Commencement This instrument commences on the day after notification. 3 Determination of Place Names I determine the names listed in the schedule as the names of the corresponding public places indicated in the associated plan in the schedule. Dorte Ekelund Delegate of the Minister 24 August 2016 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE See section 3 of the Public Place Names (Throsby) Determination 2016 (No 2) Division of Throsby – Native Fauna The location of the public places with the following names is indicated on the associated plan. NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Kaigas Street Kaigas On Mabuiag Island in the Torres Strait the word ‘Kaigas’ has the Traditional languages meaning of ‘Shovelnose shark’ in the of the Torres Strait English language. Islands. Kunapalari Kunapalari Frog Amphibian; frog Street Neobatrachus The Kunapalari Frog is a common kunapalari species in the southwest and central zones of Western Australia. The frog (Wheatbelt Frog) is usually found on clay soils. It is a moderate-sized robust species with relatively short limbs and protruding eyes. The Kunapalari Frog breeds after autumn or winter rain. It mates in milky pools where the resulting tadpoles are usually hidden from view. The call is a distinctive long, low trill. Melomys Circuit Bramble Cay melomys Mammal, native rodent Melomys rubicola A small, nocturnal native rodent unique to Bramble Cay, the most (Mosaic-tailed rat) northern island of the Great Barrier Reef in the northern Torres Strait. -

Nesting Green Turtles of Torres Strait

Final Report Nesting green turtles of Torres Strait Mark Hamann, Justin Smith, Shane Preston and Mariana Fuentes Nesting green turtles of Torres Strait Final report Mark Hamann1, Justin Smith1, Shane Preston1 and Mariana Fuentes1 1 College of Marine and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Research Program Project 2.1 Marine turtles and dugongs of the Torres Strait © JCU National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-925088-62-5 This report should be cited as: Hamann, M., Smith, J. Preston S. and Fuentes, M.M.P.B. (2015) Nesting green turtles of Torres Strait. Report to the National Environmental Research Program. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (15pp.). Published by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Research Program (NERP) Tropical Ecosystems (TE) Hub. The Tropical Ecosystems Hub is part of the Australian Government’s Commonwealth National Environmental Research Program. The NERP TE Hub is administered in North Queensland by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). The NERP Tropical Ecosystem Hub addresses issues of concern for the management, conservation and sustainable use of the World Heritage listed Great Barrier Reef (GBR) and its catchments, tropical rainforests including the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area (WTWHA), and the terrestrial and marine assets underpinning resilient communities in the Torres Strait, through the generation and transfer of world-class research and shared knowledge. This publication is copyright. The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study, research, information or educational purposes subject to inclusion of a sufficient acknowledgement of the source. -

Potential Impacts of Projected Sea-Level Rise on Sea Turtle Rookeries

AQUATIC CONSERVATION: MARINE AND FRESHWATER ECOSYSTEMS Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. (2009) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/aqc.1088 Potential impacts of projected sea-level rise on sea turtle rookeries MMPB FUENTESa,Ã, CJ LIMPUSb, M HAMANNc and J DAWSON aSchool of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Australia bQueensland Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane, Australia cSchool of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Australia ABSTRACT 1. Projected sea-level rise (SLR) is expected to cause shoreline erosion, saline intrusion into the water table and inundation and flooding of beaches and coastal areas. Areas most vulnerable to these physical impacts include small, tropical low-lying islands, which are often key habitat for threatened and endemic species, such as sea turtles. 2. Successful conservation of threatened species relies upon the ability of managers to understand current threats and to quantify and mitigate future threats to these species. This study investigated how sea-level rise might affect key rookeries (nesting grounds) (n 5 8) for the northern Great Barrier Reef (nGBR) green turtle population, the largest green turtle population in the world. 3. 3-D elevation models were developed and applied to three SLR scenarios projected by the IPCC 2007 and an additional scenario that incorporates ice melting. Results indicate that up to 38% of available nesting area across all the rookeries may be inundated as a result of SLR. 4. Flooding, as a result of higher wave run-up during storms, will increase egg mortality at these rookeries affecting the overall reproductive success of the nGBR green turtle population. -

I2I Text Paste Up

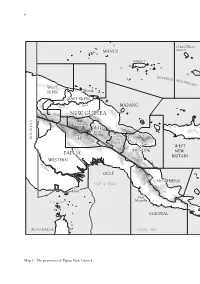

vi ST MATTHIAS MANUS GROUP MANUS I BIS MARCK ARCH IPEL AGO WEST SEPIK Wewak EAST SSEPIKEPIK River Sepik MADANG NEW GUINEA ENGA W.H. Mt Hagen M Goroka a INDONESIA S.H. rk ha E.H. m R Lae WEST MOROBEMOR PAPUA NEW BRITAIN WESTERN F ly Ri ver GULF NORTHERNOR N Gulf of Papua Daru Port Torres Strait Moresby CENTRAL AUSTRALIA CORAL SEA Map 1: The provinces of Papua New Guinea vii 0 300 kilometres 0 150 miles NEW IRELAND PACIFIC OCEAN NEW IRELAND Rabaul BOUGAINVILLE I EAST Arawa NEW BRITAIN Panguna SOLOMON SEA SOLOMON ISLANDS D ’EN N TR E C A S T E A U X MILNE BAY I S LOUISIADE ARCHIPELAGO © Carto ANU 05-031 viii W ALLAC E'S LINE SUNDALAND WALLACEA SAHULLAND 0 500 km © Carto ANU 05-031b Map 2: The prehistoric continent of Sahul consisted of the continent of Australia and the islands of New Guinea and Tasmania. ix 141 o E 142°E 143°E 144°E 144°15'E PAPUA NEW GUINEA Parama I. 9°S Daru I. 9°S Bramble Cay Missionary Reef Boigu I. Anchor Cay s f Dauan I. e East Cay Saibai I. e Deliverance I. R Stephens I. r Darnley I. Kerr (Kiss) Islet o ri ar W Yorke I. Turu Cay Mabuiag I. Yam I. Murray Islands 10°S Coconut I. 10°S Badu I. Moa I. TORRES Kubin St Pauls Warraber (Sue) I. STRAIT OUTER ISLANDS V INNER Hammond I. Thursday I. CORAL SEA ISLANDS Horn I. N Prince of Authority area Wales I. -

The Bramble Cay Melomys: the First Mammalian Extinction Due to Human-Induced Climate Change

CSIRO PUBLISHING Pacific Conservation Biology, 2017, 23, 1–3 Editorial http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/PCv23n1_ED The Bramble Cay melomys: the first mammalian extinction due to human-induced climate change Graham R. Fulton School of Veterinary and Life Sciences, Murdoch University, South Street, Murdoch WA 6150, Australia and Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane Qld 4072, Australia. Email: [email protected] The Bramble Cay melomys (Melomys rubicola) was confirmed formally described and named Melomys rubicola (the Bramble to be extinct in 2016, having disappeared somewhere between Cay melomys). He described it as ‘A comparatively large spe- late 2009 and December 2011. It is the first mammal to be cies, with a very long tail.’ On one specimen, the tail at 171 mm reported extinct due to oceanic inundation associated with was longer than the head and body combined at 140 mm. Its human-induced climate change (Gynther et al. 2016). As an general colour above was a ‘dark buffy brown’ with the nape and Australian, this abhorrent fact is cringeworthy in itself. But, middle area of the posterior back being more ‘strongly ochrac- when combined with the fact that it is the 30th terrestrial eous’ (of the colour of ochre); its under surface a dull white and mammal confirmed extinct in Australia since 1788 (Woinarski its feet whitish. Most obvious to Thomas was its long tail, which et al. 2015) y well I need an adjective well beyond abhorrence he suggested was curled at the tip and ‘perhaps more prehensile to describe my feelings. -

Climate Change Extinction' 19 February 2019

Aussie rodent becomes first 'climate change extinction' 19 February 2019 Available data on sea-level rise and weather events in the Torres Strait region "point to human-induced climate change being the root cause of the loss of the Bramble Cay melomys", a study released in 2016 said. The Melomys rubicola, considered the Great Barrier Reef's only endemic mammal species, was first discovered on the cay in 1845 by Europeans who shot the "large rats" for sport. © 2019 AFP The rat-like Bramble Cay melomys lived on a tiny island at the top of the Great Barrier Reef and had not been seen in a decade Australia officially declared a Great Barrier Reef rodent extinct on Tuesday, making it the first mammal believed to have been killed off by human- induced climate change. The rat-like Bramble Cay melomys—whose only known habitat was a small sandy island in far northern Australia—has not been spotted in a decade. Researchers from Queensland determined a key factor in its disappearance was "almost certainly" repeated ocean inundation of the cay—a low-lying island on a coral reef—over the last decade, which had resulted in dramatic habitat loss. Australia's environment ministry on Tuesday said it had officially transferred the animal to the "extinct" list. The declaration was expected. The researchers completed a wide-ranging survey in 2014 in a bid to track down the species, but found no trace. 1 / 2 APA citation: Aussie rodent becomes first 'climate change extinction' (2019, February 19) retrieved 28 September 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2019-02-aussie-rodent-climate-extinction.html This document is subject to copyright. -

E Res E T Rtle

E E T FT RTLE RES UR ES~ Proceedings of a Seminar held jointly by Applied Ecology Pty Ltd and the Department of Tropical Veterinary Science Research Monograph 1 JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY OF NORTH QUEENSLAND MANAGEMENT OF TURTLE RESOURCES RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 1 ERRATA Please amend as follows: • On. :ttile. page., a6:te,,'t 11 Ve_paA;tme.n:t 06 Tnopic.ai. Ve;te!Un.any Sue.nee." add "at Towviov.lUe., Q.td., AuJ.,:tJLa.tia, Z8 Ju.vie. 19 79". • "VJ[. J. Pcvune.n:teJ1! 1 on page 3 to "Vn C.J. Pcvune.n:teJL". 11 J • Po./LJn en:te.n" o n. pag ell 4 and Z3 to "C • J • Pcvune.n:te.f[". • I vi Figu.he. Z on. page. Z6 ,the. le.g e.nd .6 twu£d appe.an M : H - Hut * - Ug h:tho u.J.i e. ·-- - S.H.T.L. 15 Oc.tobe.n 1978 - S.H.T.L. ,z9 Manc.h 1979 - Veg e:tatio n Mang in • I nte.nc.hang e Fig u.ne nwnb e.n "3" and c,ap;t,,i,o vi ("Size and .oe.xu.ai. dlo:t!Libu.;tion 06 Chelonia myda.o .o.tau.gh:teJLed a:t Yonke I.6.tand ZZ Oc.:tobe.n 1976-30 Ju.vie 7977") on page 29 wLth Figu.ne nwnbe.n "4" and c.ap:Uon ("Size dlo:t!Libu.;tion o 6 non- ne>.i:Ung Che.lo VLia mydM c.ap:tU/'Led 2 Z Oc.:tobe.n 1976-30 Ju.vie 7977") on page 30.