Rediscovering the Celestial Cuneiform Puns That Imparted the "Birth of Pegasus" Myth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dunhuang Chinese Sky: a Comprehensive Study of the Oldest Known Star Atlas

25/02/09JAHH/v4 1 THE DUNHUANG CHINESE SKY: A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF THE OLDEST KNOWN STAR ATLAS JEAN-MARC BONNET-BIDAUD Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique ,Centre de Saclay, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France E-mail: [email protected] FRANÇOISE PRADERIE Observatoire de Paris, 61 Avenue de l’Observatoire, F- 75014 Paris, France E-mail: [email protected] and SUSAN WHITFIELD The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents an analysis of the star atlas included in the medieval Chinese manuscript (Or.8210/S.3326), discovered in 1907 by the archaeologist Aurel Stein at the Silk Road town of Dunhuang and now held in the British Library. Although partially studied by a few Chinese scholars, it has never been fully displayed and discussed in the Western world. This set of sky maps (12 hour angle maps in quasi-cylindrical projection and a circumpolar map in azimuthal projection), displaying the full sky visible from the Northern hemisphere, is up to now the oldest complete preserved star atlas from any civilisation. It is also the first known pictorial representation of the quasi-totality of the Chinese constellations. This paper describes the history of the physical object – a roll of thin paper drawn with ink. We analyse the stellar content of each map (1339 stars, 257 asterisms) and the texts associated with the maps. We establish the precision with which the maps are drawn (1.5 to 4° for the brightest stars) and examine the type of projections used. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Classical Images – Greek Pegasus

Classical images – Greek Pegasus Red-figure kylix crater Attic Red-figure kylix Triptolemus Painter, c. 460 BC attr Skythes, c. 510 BC Edinburgh, National Museums of Scotland Boston, MFA (source: theoi.com) Faliscan black pottery kylix Athena with Pegasus on shield Black-figure water jar (Perseus on neck, Pegasus with Etrurian, attr. the Sokran Group, c. 350 BC Athenian black-figure amphora necklace of bullae (studs) and wings on feet, Centaur) London, The British Museum (1842.0407) attr. Kleophrades pntr., 5th C BC From Vulci, attr. Micali painter, c. 510-500 BC 1 New York, Metropolitan Museum of ART (07.286.79) London, The British Museum (1836.0224.159) Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus Pegasus Attic, red-figure plate, c. 420 BC Source: Wikimedia (Rome, Palazzo Massimo exh) 2 Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus London, The British Museum Virginia, Museum of Fine Arts exh (The Horse in Art) Pegasus Red-figure oinochoe Apulian, c. 320-10 BC 3 Boston, MFA Classical images – Greek Pegasus Silver coin (Pegasus and Athena) Silver coin (Pegasus and Lion/Bull combat) Corinth, c. 415-387 BC Lycia, c. 500-460 BC London, The British Museum (Ac RPK.p6B.30 Cor) London, The British Museum (Ac 1979.0101.697) Silver coin (Pegasus protome and Warrior (Nergal?)) Silver coin (Arethusa and Pegasus Levantine, 5th-4th C BC Graeco-Iberian, after 241 BC London, The British Museum (Ac 1983, 0533.1) London, The British Museum (Ac. 1987.0649.434) 4 Classical images – Greek (winged horses) Pegasus Helios (Sol-Apollo) in his chariot Eos in her chariot Attic kalyx-krater, c. -

Chasing Constellations

MITCHELL, GRACE LYN Gracelyn Mitchell Age: 17, Grade: 12 Home School, Wetumpka, AL Educator: Shunta McCants Category: Personal Essay & Memoir Chasing Constellations I stood in the wet grass, scrunching my toes in and out, letting the cool dew drops fall on my bare feet. My thin, white sundress and my thin, almost-white hair fluttering around me in the wind. I stood firmly, watching the glow of what felt like trillions of fireflies fade in and out. Each time the one I had my gaze set on flickered out, I would close my eyes and inhale deeply, breathing in the scent of summer air and what I can still only describe as “magic”. The cool air on my sticky, sweaty skin felt good. My stomach still churned with nausea from seconds ago when my cousin and her best friend twirled me around on the “swing” made from a single branch and piece of rope tied to a tree in their backyard...over, and over, and over. But I still giggled past the dizziness every time. I smiled and laughed to myself. My heart fluttered and my veins surged with what I look back on as “child euphoria”. My cousin, with long, steaming brown hair, ran up beside me followed by her friend. Still giggling, she grasped my shoulders and pointed to the sky. “You see that, Grace? That’s the pegasus constellation.” She pointed to an outline of stars that unmistakably made up the image of a chubby pegasus with a bridle and saddle and very two-dimensional wings. It wasn’t one of those constellations that you had to squint at, or one that you had to imagine most of the image yourself for. -

Astronomy Alphabet

Astronomy Alphabet Educational video for children Teacher https://vimeo.com/77309599 & Learner Guide This guide gives background information about the astronomy topics mentioned in the video, provides questions and answers children may be curious about, and suggests topics for discussion. Alhazen A Alhazen, called the Father of Optics, performed NASA/Goddard/Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, Apollo 17 experiments over a thousand years ago Can you find Alhazen crater when you look at the Moon? to learn about how light travels and Why does the Moon look bigger near the behaves. He also studied astronomy, horizon? separated light into colors, and sought to Believe it or not, scientists still don’t know for sure why explain why the Moon looks bigger near we perceive the Moon to be larger when it lies near to the the horizon. horizon. Though photos of the Moon at different points in the sky show it to be the same size, we humans think we I’ve never heard of Abu Ali al-Hasan ibn al- see something quite different. Try this experiment yourself Hasan ibn al-Hatham (Alhazen). sometime! One possibility is that objects we see next to the Tell me more about him. Moon when it’s near to them give us the illusion that it’s We don’t know that much about Alhazen be- bigger, because of a sense of scale and reference. cause he lived so long ago, but we do know that he was born in Persia in 965. He wrote hundreds How many craters does the Moon have, and what of books on math and science and pioneered the are their names? scientific method of experimentation. -

Astronomy 113 Laboratory Manual

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON Department of Astronomy Astronomy 113 Laboratory Manual Fall 2011 Professor: Snezana Stanimirovic 4514 Sterling Hall [email protected] TA: Natalie Gosnell 6283B Chamberlin Hall [email protected] 1 2 Contents Introduction 1 Celestial Rhythms: An Introduction to the Sky 2 The Moons of Jupiter 3 Telescopes 4 The Distances to the Stars 5 The Sun 6 Spectral Classification 7 The Universe circa 1900 8 The Expansion of the Universe 3 ASTRONOMY 113 Laboratory Introduction Astronomy 113 is a hands-on tour of the visible universe through computer simulated and experimental exploration. During the 14 lab sessions, we will encounter objects located in our own solar system, stars filling the Milky Way, and objects located much further away in the far reaches of space. Astronomy is an observational science, as opposed to most of the rest of physics, which is experimental in nature. Astronomers cannot create a star in the lab and study it, walk around it, change it, or explode it. Astronomers can only observe the sky as it is, and from their observations deduce models of the universe and its contents. They cannot ever repeat the same experiment twice with exactly the same parameters and conditions. Remember this as the universe is laid out before you in Astronomy 113 – the story always begins with only points of light in the sky. From this perspective, our understanding of the universe is truly one of the greatest intellectual challenges and achievements of mankind. The exploration of the universe is also a lot of fun, an experience that is largely missed sitting in a lecture hall or doing homework. -

Sumerian Liturgical Texts

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM PUBLICATIONS OF THE BABYLONIAN SECTION VOL. X No. 2 SUMERIAN LITURGICAL TEXTS BY g600@T STEPHEN LANGDON ,.!, ' PHILADELPHIA PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM 1917 DIVINITY LIBRARY gJ-37 . f's- ". /o, ,7'Y,.'j' CONTENTS INTRODUC1'ION ................................... SUMERIAN LITURGICAL TEXTS: EPICALPOEM ON THE ORIGINOF SLIMERIANCIVILI- ZATION ...................................... LAMENTATIONTO ARURU......................... PENITENTIALPSALM TO GOD AMURRU............. LAMENTATIONON THE INVASION BY GUTIUM....... LEGENDOF GILGAMISH........................... LITURGICALHYMN TO UR-ENGUR............. .. .. LITURGICALHYMN TO DUNGI...................... LITURGICALHYMN TO LIBIT-ISHTAR(?)OR ISHME- DAGAN(?)................................... LITURGICALHYMN TO ISHME-DAGAN............... LAMENTATIONON THE DESTRUCTIONOF UR ........ HYMNOF SAMSUILUNA........................... LITURGYTO ENLIL.babbar-ri babbar.ri.gim. INCLUD- ING A TRANSLATIONOF SBH 39 .............. FRAGMENTFROM THE TITULARLITANY OF A LITURGY LITURGICALHYMN TO ISHME.DAGAN............... LITURGYTO INNINI ............................... INTRODUCTION Under the title SUMERIANLITURGICAL TEXTS the author has collected the material of the Nippur collection which belonged to the various public song services of the Sumerian and Babylonian temples. In this category he has included the epical and theological poems called lag-sal. These long epical compositions are the work of a group of scholars at Nippur who ambitiously planned to write a series -

Guide to the Constellations

STAR DECK GUIDE TO THE CONSTELLATIONS BY MICHAEL K. SHEPARD, PH.D. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Constellations by Season 3 Guide to the Constellations Andromeda, Aquarius 4 Aquila, Aries, Auriga 5 Bootes, Camelopardus, Cancer 6 Canes Venatici, Canis Major, Canis Minor 7 Capricornus, Cassiopeia 8 Cepheus, Cetus, Coma Berenices 9 Corona Borealis, Corvus, Crater 10 Cygnus, Delphinus, Draco 11 Equuleus, Eridanus, Gemini 12 Hercules, Hydra, Lacerta 13 Leo, Leo Minor, Lepus, Libra, Lynx 14 Lyra, Monoceros 15 Ophiuchus, Orion 16 Pegasus, Perseus 17 Pisces, Sagitta, Sagittarius 18 Scorpius, Scutum, Serpens 19 Sextans, Taurus 20 Triangulum, Ursa Major, Ursa Minor 21 Virgo, Vulpecula 22 Additional References 23 Copyright 2002, Michael K. Shepard 1 GUIDE TO THE STAR DECK Introduction As an introduction to astronomy, you cannot go wrong by first learning the night sky. You only need a dark night, your eyes, and a good guide. This set of cards is not designed to replace an atlas, but to engage your interest and teach you the patterns, myths, and relationships between constellations. They may be used as “field cards” that you take outside with you, or they may be played in a variety of card games. The cultural and historical story behind the constellations is a subject all its own, and there are numerous books on the subject for the curious. These cards show 52 of the modern 88 constellations as designated by the International Astronomical Union. Many of them have remained unchanged since antiquity, while others have been added in the past century or so. The majority of these constellations are Greek or Roman in origin and often have one or more myths associated with them. -

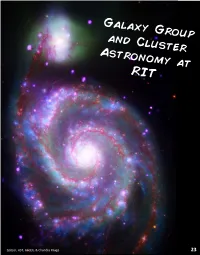

Galaxy Group and Cluster Astronomy at RIT

Galaxy Group and Cluster Astronomy at RIT 23 Spitzer,)HST,)GALEX,)&)Chandra)Image) Green Bank 100M Hershel 3.5M Credit:)NRAO) Credit:)Chicago)University) Hubble Space Telescope (HST) Sloan Digital 2.4M Sky Survey 2.5M Credit:) Hubblesite ) In Space On Earth Astronomers at RIT want to learn about galaxy groups and clusters. They use a variety of ground- and space-based telescopes. 24 YOU ARE HERE Milky Way galaxy Artist’s representation Here’s where the sun lives! We are on the outskirts of the Milky Way. It takes the sun 200 million years to travel once around the galaxy. Credit:)NASA/JPLJCaltech/R) 25 Sometimes galaxies run past each other or even combine! ZOOM Antennae Galaxies This can jumpstart star formation and make irregularly shaped galaxies like the ones shown here. 26 Credit:)HubbleSite) Living as a group of galaxies, the Milky Way has neighbors: the larger Andromeda and the smaller Tr i a n g u l u m . The Milky Way s Home The Local Group Andromeda Galaxy This is an artist’s interpretation. NGC185 Not drawn to scale. NGC147 M32 Tr i a n g u l u m Galaxy NGC205 Pegasus Milky Way Galaxy IC1613 Draco Fornax WLM Ursa Minor Sculptor LEo I Leo II Sextans NGC6822 SMC LMC Carina Artist’s representation of the Local Group Around each larger galaxy there are dozens of dwarf galaxies. It takes light 2.5 million years to get to Earth from Andromeda. 27 Hundreds, or even thousands, of galaxies can live together in a cluster. A crowded neighborhood Abell 1689 shown here has over 2000 galaxies living far, far away from Earth. -

The Transcription of West Semitic Names in the Prosobab Database (V.01 Published 03/2019) Rieneke Sonnevelt

The transcription of West Semitic names in the Prosobab Database (V.01 published 03/2019) Rieneke Sonnevelt Basic principles For the transcription of West Semitic names in the Prosobab database the Akkadian spelling serves as point of departure. For instance, West Semitic gutturals, vowels, or vowel length are not reconstructed, if not (consistently) represented. Moreover, it is not always possible to discern whether a name is Akkadian or West Semitic. Should, for example, Iba-ni-ia be read as Akkadian Bānia or is it the West Semitic name Banī? In these instances the Akkadian form is given precedence. For the sake of utility, harmonisation is sometimes favoured. Several theophoric elements are transcribed in a uniform way despite the fact that individual orthographies display much variation (see Iltehr and Tammeš below). Occasionally, a standard version is required in an individual’s passport (see Adad and Nusku). As a result of these principles, there will always be a margin of error. For a more in-depth reconstruction of linguistic features or orthographic diversity of a certain name type, the spellings contained in the database may be consulted. Below, the transcription of the following components is dealt with: (1) theophoric elements, (2) verbal complements, (3) passive forms, (4) suffixes, (5) the consonant Ayin. The transcription of West Semitic names in the Prosobab database 1. Theophoric elements 1.a Common Semitic ˀl ˀl, the most common theophoric element in West Semitic names, appears in a variety of syllabic orthographies, such as il-; -i-lu; -i-li; -il-lu; -il-li; -Ci-lu; -i-il. -

Sargon of Akkade and His God

Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 69 (1), 63–82 (2016) DOI: 10.1556/062.2016.69.1.4 SARGON OF AKKADE AND HIS GOD COMMENTS ON THE WORSHIP OF THE GOD OF THE FATHER AMONG THE ANCIENT SEMITES STEFAN NOWICKI Institute of Classical, Mediterranean and Oriental Studies, University of Wrocław ul. Szewska 49, 50-139 Wrocław, Poland e-mail: [email protected] The expression “god of the father(s)” is mentioned in textual sources from the whole area of the Fertile Crescent, between the third and first millennium B.C. The god of the fathers – aside from assumptions of the tutelary deity as a god of ancestors or a god who is a deified ancestor – was situated in the centre and the very core of religious life among all peoples that lived in the ancient Near East. This paper is focused on the importance of the cult of Ilaba in the royal families of the ancient Near East. It also investigates the possible source and route of spreading of the cult of Ilaba, which could have been created in southern Mesopotamia, then brought to other areas. Hypotheti- cally, it might have come to the Near East from the upper Euphrates. Key words: religion, Ilaba, royal inscriptions, Sargon of Akkade, god of the father, tutelary deity, personal god. The main aim of this study is to trace and describe the worship of a “god of the fa- ther”, known in Akkadian sources under the name of Ilaba, and his place in the reli- gious life of the ancient peoples belonging to the Semitic cultural circle. -

Download Star Chart

10:00 pm on August 1 N 9:00 pm on August 15 8:00 pm on September 1 To use this chart: hold the chart in front of you and turn it so the direction you are facing is at the bottom of the CASSIOPEIA 2021 chart. Polaris MAJOR ANDROMEDA Bright Stars URSA Medium Bright Stars Faint Stars M-31 DIPPER CEPHEUS LITTLE UGUST Scan dark skies PEGASUS A BIG DIPPER with binoculars: DRACO Deneb M-6: The Buttery Cluster CYGNUS SQUARE OF SQUARE M-7: Open star cluster PEGASUS M-13 GREAT COMA M-8: The Lagoon Nebula LYRA BERENICES E HERCULES M-27 BOÖTES M-13: Globular star cluster W M-15: Globular star cluster Altair Vega CORONA Arcturus BOREALIS M-22: Globular star cluster M-15 SUMMER TRIANGLE M-27: Dumbell Nebula Jupiter SERPENS VIRGO AQUILA CAPUT M-31: The Andromeda Galaxy SERPENS CAUDA Spica CAPRICORNUS Full Moon From Nashville: M-22 Aug 22 OPHIUCHUS Sunrise Sunset LIBRA Aug 1 5:54 AM 7:53 PM M-8 Saturn Aug 15 6:05 AM 7:38 PM M-6 SAGITTARIUS Last Quarter Sept 1 6:19 AM 7:16 PM Antares Aug 30 M-7 SCORPIUS New Moon S Aug 8 Download monthly star charts and learn First Quarter more about our shows at adventuresci.org Aug 15 Early Morning August 2021 As the Earth orbits the Sun throughout the year, the After Sunset Low in the south is the hook-shaped constellation Scorpius the constellations rise and set just a little bit earlier every Scorpion low in the south.