Astronomy 113 Laboratory Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity Challenge Has So Much Program Work in It That It Requires Two Meetings to Complete

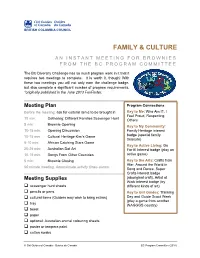

BRITISH COLUMBIA COUNCIL FAMILY & CULTURE AN INSTANT MEETING FOR BROWNIES FROM THE BC PROGRAM COMMITTEE The BC Diversity Challenge has so much program work in it that it requires two meetings to complete. It is worth it, though! With these two meetings you will not only earn the challenge badge, but also complete a significant number of program requirements. *originally published in the June 2013 FunFinder. Meeting Plan Program Connections Before the meeting: ask for cultural items to be brought in Key to Me: Who Am I?, I Feel Proud, Respecting 10 min: Gathering: Different Families Scavenger Hunt Others 5 min: Brownie Opening Key to My Community: 10-15 min: Opening Discussion Family Heritage interest 10-15 min: Cultural Heritage Kim’s Game badge (special family treasure) 5-10 min: African Catching Stars Game Key to Active Living: Go 20-25 min: Australian Dot Art For It! Interest badge (play an 10-15 min: Songs From Other Countries active game) 5 min: Brownie Closing Key to the Arts: Crafts from Afar, Around the World in 90 minute meeting. Approximate activity times shown. Song and Dance, Super Crafts interest badge Meeting Supplies (aboriginal craft), Artist at Work interest badge (try scavenger hunt sheets different kinds of art) pencils or pens Key to Girl Guides: Thinking cultural items (Guiders may wish to bring extras) Day and Guide Scout Week (play a game from another tray WAGGGS country) towel paper optional: Australian animal colouring sheets poster or tempera paint cotton swabs © Girl Guides of Canada - Guides du Canada BC Program Committee (2014) FAMILY & CULTURE INSTANT MEETING FOR BROWNIES P a g e 2 Gathering: Different Families Scavenger Hunt Directions Instead of talking about different kinds of families (as Supplies suggested in the challenge document), have the girls scavenger hunt sheet mingle and see if they can find someone to fit in each of the (next page) boxes on the next page. -

The Planisphere of the Heavens

The Planisphere of the Heavens by Steven E. Behrmann Book V Copyright© by Steven E. Behrmann All rights reserved 2010 First Draft (Sunnyside Edition) Dedication: This book is dedicated to my blessed little son, Jonathan William Edward, to whom I hope to teach the names of the stars. Table of Contents A Planisphere of the Heavens .......................................................... 12 The Signs of the Seasons ................................................................. 15 The Virgin (Virgo) ........................................................................... 24 Virgo ............................................................................................ 25 Coma ............................................................................................ 27 The Centaur .................................................................................. 29 Boötes ........................................................................................... 31 The Scales (Libra) ............................................................................ 34 Libra ............................................................................................. 35 The Cross (Crux) .......................................................................... 37 The Victim ................................................................................... 39 The Crown .................................................................................... 41 The Scorpion ................................................................................... -

Aquarius Aries Pisces Taurus

Zodiac Constellation Cards Aquarius Pisces January 21 – February 20 – February 19 March 20 Aries Taurus March 21 – April 21 – April 20 May 21 Zodiac Constellation Cards Gemini Cancer May 22 – June 22 – June 21 July 22 Leo Virgo July 23 – August 23 – August 22 September 23 Zodiac Constellation Cards Libra Scorpio September 24 – October 23 – October 22 November 22 Sagittarius Capricorn November 23 – December 23 – December 22 January 20 Zodiac Constellations There are 12 zodiac constellations that form a belt around the earth. This belt is considered special because it is where the sun, the moon, and the planets all move. The word zodiac means “circle of figures” or “circle of life”. As the earth revolves around the sun, different parts of the sky become visible. Each month, one of the 12 constellations show up above the horizon in the east and disappears below the horizon in the west. If you are born under a particular sign, the constellation it is named for can’t be seen at night. Instead, the sun is passing through it around that time of year making it a daytime constellation that you can’t see! Aquarius Aries Cancer Capricorn Gemini Leo January 21 – March 21 – June 22 – December 23 – May 22 – July 23 – February 19 April 20 July 22 January 20 June 21 August 22 Libra Pisces Sagittarius Scorpio Taurus Virgo September 24 – February 20 – November 23 – October 23 – April 21 – August 23 – October 22 March 20 December 22 November 22 May 21 September 23 1. Why is the belt that the constellations form around the earth special? 2. -

KMP LIST E:\New Songs\New Videos\Eminem\ Eminem

_KMP_LIST E:\New Songs\New videos\Eminem\▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\blame it on me.mpgblame it on me.mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\I Just had.mp4I Just had.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\Shut It Down.flvShut It Down.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\03. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com). mp303. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com).mp3 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon - mr lonely(2).mpegakon - mr lonely(2).mpeg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpgAkon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Right Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flvAkon - Righ t Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blog spot.com.mkvAkon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blogspot.com.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.aviAkon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Vid eo (New Song 2013) HD.MP4Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Video (N ew Song 2013) HD.MP4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft.Kardinal Offishall & Colby O'Donis - Beauti ful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] ft.Kardinal Offish all & Colby O'Donis - Beautiful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] om.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon-i wanna love you.aviakon-i wanna love you.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\David Guetta feat. -

Summer Constellations

Night Sky 101: Summer Constellations The Summer Triangle Photo Credit: Smoky Mountain Astronomical Society The Summer Triangle is made up of three bright stars—Altair, in the constellation Aquila (the eagle), Deneb in Cygnus (the swan), and Vega Lyra (the lyre, or harp). Also called “The Northern Cross” or “The Backbone of the Milky Way,” Cygnus is a horizontal cross of five bright stars. In very dark skies, Cygnus helps viewers find the Milky Way. Albireo, the last star in Cygnus’s tail, is actually made up of two stars (a binary star). The separate stars can be seen with a 30 power telescope. The Ring Nebula, part of the constellation Lyra, can also be seen with this magnification. In Japanese mythology, Vega, the celestial princess and goddess, fell in love Altair. Her father did not approve of Altair, since he was a mortal. They were forbidden from seeing each other. The two lovers were placed in the sky, where they were separated by the Celestial River, repre- sented by the Milky Way. According to the legend, once a year, a bridge of magpies form, rep- resented by Cygnus, to reunite the lovers. Photo credit: Unknown Scorpius Also called Scorpio, Scorpius is one of the 12 Zodiac constellations, which are used in reading horoscopes. Scorpius represents those born during October 23 to November 21. Scorpio is easy to spot in the summer sky. It is made up of a long string bright stars, which are visible in most lights, especially Antares, because of its distinctly red color. Antares is about 850 times bigger than our sun and is a red giant. -

Chapter 3: Familiarizing Yourself with the Night Sky

Chapter 3: Familiarizing Yourself With the Night Sky Introduction People of ancient cultures viewed the sky as the inaccessible home of the gods. They observed the daily motion of the stars, and grouped them into patterns and images. They assigned stories to the stars, relating to themselves and their gods. They believed that human events and cycles were part of larger cosmic events and cycles. The night sky was part of the cycle. The steady progression of star patterns across the sky was related to the ebb and flow of the seasons, the cyclical migration of herds and hibernation of bears, the correct times to plant or harvest crops. Everywhere on Earth people watched and recorded this orderly and majestic celestial procession with writings and paintings, rock art, and rock and stone monuments or alignments. When the Great Pyramid in Egypt was constructed around 2650 BC, two shafts were built into it at an angle, running from the outside into the interior of the pyramid. The shafts coincide with the North-South passage of two stars important to the Egyptians: Thuban, the star closest to the North Pole at that time, and one of the stars of Orion’s belt. Orion was The Ishango Bone, thought to be a 20,000 year old associated with Osiris, one of the Egyptian gods of the lunar calendar underworld. The Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, built by Plains Indians, consists of rocks in the shape of a large circle, with lines radiating from a central hub like the spokes of a bicycle wheel. -

History of Astrometry

5 Gaia web site: http://sci.esa.int/Gaia site: web Gaia 6 June 2009 June are emerging about the nature of our Galaxy. Galaxy. our of nature the about emerging are More detailed information can be found on the the on found be can information detailed More technologies developed by creative engineers. creative by developed technologies scientists all over the world, and important conclusions conclusions important and world, the over all scientists of the Universe combined with the most cutting-edge cutting-edge most the with combined Universe the of The results from Hipparcos are being analysed by by analysed being are Hipparcos from results The expression of a widespread curiosity about the nature nature the about curiosity widespread a of expression 118218 stars to a precision of around 1 milliarcsecond. milliarcsecond. 1 around of precision a to stars 118218 trying to answer for many centuries. It is the the is It centuries. many for answer to trying created with the positions, distances and motions of of motions and distances positions, the with created will bring light to questions that astronomers have been been have astronomers that questions to light bring will accuracies obtained from the ground. A catalogue was was catalogue A ground. the from obtained accuracies Gaia represents the dream of many generations as it it as generations many of dream the represents Gaia achieving an improvement of about 100 compared to to compared 100 about of improvement an achieving orbit, the Hipparcos satellite observed the whole sky, sky, whole the observed satellite Hipparcos the orbit, ear Y of them in the solar neighbourhood. -

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

The PLATO Antarctic Site Testing Observatory

PROCEEDINGS OF SPIE SPIEDigitalLibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie The PLATO Antarctic site testing observatory J. S. Lawrence, G. R. Allen, M. C. B. Ashley, C. Bonner, S. Bradley, et al. J. S. Lawrence, G. R. Allen, M. C. B. Ashley, C. Bonner, S. Bradley, X. Cui, J. R. Everett, L. Feng, X. Gong, S. Hengst, J. Hu, Z. Jiang, C. A. Kulesa, Y. Li, D. Luong-Van, A. M. Moore, C. Pennypacker, W. Qin, R. Riddle, Z. Shang, J. W. V. Storey, B. Sun, N. Suntzeff, N. F. H. Tothill, T. Travouillon, C. K. Walker, L. Wang, J. Yan, J. Yang, H. Yang, D. York, X. Yuan, X. G. Zhang, Z. Zhang, X. Zhou, Z. Zhu, "The PLATO Antarctic site testing observatory," Proc. SPIE 7012, Ground-based and Airborne Telescopes II, 701227 (10 July 2008); doi: 10.1117/12.787166 Event: SPIE Astronomical Telescopes + Instrumentation, 2008, Marseille, France Downloaded From: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie on 7/12/2018 Terms of Use: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/terms-of-use The PLATO Antarctic site testing observatory J.S. Lawrence*a, G.R. Allenb, M.C.B. Ashleya, C. Bonnera, S. Bradleyc, X. Cuid, J.R. Everetta, L. Fenge, X. Gongd, S. Hengsta, J.Huf, Z. Jiangf, C.A. Kulesag, Y. Lih, D. Luong-Vana, A.M. Moorei, C. Pennypackerj, W. Qinh, R. Riddlek, Z. Shangl, J.W.V. Storeya, B. Sunh, N. Suntzeffm, N.F.H. Tothilln, T. Travouilloni, C.K. Walkerg, L. Wange/m, J. Yane/f, J. Yange, H.Yangh, D. Yorko, X. Yuand, X.G. -

Science in Nasa's Vision for Space Exploration

SCIENCE IN NASA’S VISION FOR SPACE EXPLORATION SCIENCE IN NASA’S VISION FOR SPACE EXPLORATION Committee on the Scientific Context for Space Exploration Space Studies Board Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. Support for this project was provided by Contract NASW 01001 between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors. International Standard Book Number 0-309-09593-X (Book) International Standard Book Number 0-309-54880-2 (PDF) Copies of this report are available free of charge from Space Studies Board National Research Council The Keck Center of the National Academies 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, DC 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area); Internet, http://www.nap.edu. Copyright 2005 by the National Academy of Sciences. -

An Overview of New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics About the National Academies

2020 VISION An Overview of New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics About the National Academies The National Academies—comprising the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council—work together to enlist the nation’s top scientists, engineers, health professionals, and other experts to study specific issues in science, technology, and medicine that underlie many questions of national importance. The results of their deliberations have inspired some of the nation’s most significant and lasting efforts to improve the health, education, and welfare of the United States and have provided independent advice on issues that affect people’s lives worldwide. To learn more about the Academies’ activities, check the website at www.nationalacademies.org. Copyright 2011 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America This study was supported by Contract NNX08AN97G between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Contract AST-0743899 between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Science Foundation, and Contract DE-FG02-08ER41542 between the National Academy of Sciences and the U.S. Department of Energy. Support for this study was also provided by the Vesto Slipher Fund. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the agencies that provided support for the project. 2020 VISION An Overview of New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics Committee for a Decadal Survey of Astronomy and Astrophysics ROGER D.