Television News and the Politics of Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inland & Coastal

September 2010 Alicantewww.thetraderonline.es - Valencia - Castellon • Tel 902733622 - Tarragona - Barcelona FREE! 1 Inland & Coastal rader Authorised Dealer SOUTH EDITION - SEPTEMBER 2010 Issue 143 www.thetraderonline.es Tel 902733633 T Want to save Money? See page 2 Buying and selling stuff at .com FIREWOOD PARRA Valencia province ablaze Be ready for Winter 2010-2011 FLAMES are licking almost every corner of the prov- Buy the logs now ince of Valencia as forest fi res that started early this week continue to burn with a vengeance. Thought Tel 962246486 696320315 to be the work of arsonists, the inferno sweeping across the south of the province shows no signs of www.lenasparra.com abating and has led to smoke-clouded skies within a 30-kilometre radius of each of the focal points of the fi res. The worst to date have been two fi res that FORMER UK MARSHALLS started almost simultaneously in Bocairent and On- REGISTERED CONTRACTOR tinyent. All homes outside the main hub of the town All aspects of building work and in Ontinyent were evacuated on Monday night, with hard landscaping many people’s houses just inches from the fl ames. Certifi cates & Portfolio availbale The blaze looked set to destroy everything their oc- cupants owned, but the wind changed in the early Tel Gary 962728195 678946301 hours of Tuesday morning, giving them a temporary reprieve. Further south, Simat de la Valldigna has turned into a raging inferno with a massive column The Magpies Is under new ownership. of smoke blocking out the sun, and even the fl ames David & Carol Welcome being visible from as far away as Oliva, at a dis- New & Old Customers tance of over 30 kilometres. -

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee S4C Written evidence - web List of written evidence 1 URDD 3 2 Hugh Evans 5 3 Ron Jones 6 4 Dr Simon Brooks 14 5 The Writers Guild of Great Britain 18 6 Mabon ap Gwynfor 23 7 Welsh Language Board 28 8 Ofcom 34 9 Professor Thomas P O’Malley, Aberystwth University 60 10 Tinopolis 64 11 Institute of Welsh Affairs 69 12 NUJ Parliamentary Group 76 13 Plaim Cymru 77 14 Welsh Language Society 85 15 NUJ and Bectu 94 16 DCMS 98 17 PACT 103 18 TAC 113 19 BBC 126 20 Mercator Institute for Media, Languages and Culture 132 21 Mr S.G. Jones 138 22 Alun Ffred Jones AM, Welsh Assembly Government 139 23 Celebrating Our Language 144 24 Peter Edwards and Huw Walters 146 2 Written evidence submitted by Urdd Gobaith Cymru In the opinion of Urdd Gobaith Cymru, Wales’ largest children and young people’s organisation with 50,000 members under the age of 25: • The provision of good-quality Welsh language programmes is fundamental to establishing a linguistic context for those who speak Welsh and who wish to learn it. • It is vital that this is funded to the necessary level. • A good partnership already exists between S4C and the Urdd, but the Urdd would be happy to co-operate and work with S4C to identify further opportunities for collaboration to offer opportunities for children and young people, thus developing new audiences. • We believe that decisions about the development of S4C should be made in Wales. -

1 Sport Mega-Events and a Legacy of Increased

SPORT MEGA-EVENTS AND A LEGACY OF INCREASED SPORT PARTICIPATION: AN OLYMPIC PROMISE OR AN OLYMPIC DREAM? KATHARINE HELEN HUGHES A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Leeds Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. JANUARY 2013 1 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 7 Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 8 Student’s declaration ....................................................................................................... 10 List of Tables and Figures ................................................................................................ 11 List of Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 12 Preface ............................................................................................................................ 14 Chapter 1: Context of the study ....................................................................................... 17 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 17 1.2 Structure of the thesis ......................................................................................................... 19 1.3 Research aims and questions .......................................................................................... -

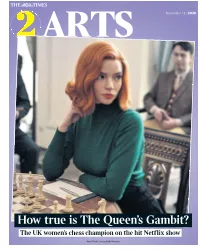

How True Is the Queen's Gambit?

ARTS November 13 | 2020 How true is The Queen’s Gambit? The UK women’s chess champion on the hit Netflix show Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon 2 1GT Friday November 13 2020 | the times times2 Caitlin 6 4 DOWN UP Moran Demi Lovato Quote of It’s hard being a former Disney child the Weekk star. Eventually you have to grow Celebrity Watch up, despite the whole world loving And in New!! and remembering you as a cute magazine child, and the route to adulthood the Love for many former child stars is Island star paved with peril. All too often the Priscilla way that young female stars show Anyabu they are “all grown up” is by Going revealed her Sexy: a couple of fruity pop videos; preferred breakfast, 10 a photoshoot in PVC or lingerie. which possibly 8 “I have lost the power of qualifies as “the most adorableness, but I have gained the unpleasant breakfast yet invented DOWN UP power of hotness!” is the message. by humankind”. Mary Dougie from Unfortunately, the next stage in “Breakfast is usually a bagel with this trajectory is usually “gaining cheese spread, then an egg with grated Wollstonecraft McFly the power of being in your cheese on top served with ketchup,” This week the long- There are those who say that men mid-thirties and putting on 2st”, she said, madly admitting with that awaited statue of can’t be feminists and that they cannot a power that sadly still goes “usually” that this is something that Mary Wollstonecraft help with the Struggle. -

Class of 2005 Class of 2005

AUTUMN 2005 AA MagazineMagazine forfor GraduatesGraduates && FriendsFriends ofof Queen’sQueen’s UniversityUniversity BelfastBelfast £1m£1m UnionUnion AppeaAppeall SportSport forfor AAllll ClassClass ofof 20020055 Supported by BlueBlueZoe bellbel Salmonlee The best view of Belfast! As Domestic Bursar at Stranmillis University College, Christine Nesbitt is no stranger to visiting conferences. A Catering Administration graduate of the University of Ulster, Christine has been at Stranmillis for 11 years and was appointed Domestic Bursar in 2001. Christine Nesbitt Christine and her team are who were pleasantly surprised at how topics and visits to historical sites. responsible for the full range of convenient it was to travel to Belfast So to ensure that visitors would get housekeeping and catering services and to the College, it was unanimously the best view of Belfast we provided for conferences, which now agreed that the conference should contacted BVCB. form a regular part of the out-of term come to Northern Ireland for the first business at Stranmillis. Christine time. ‘BVCB have been extremely helpful, explains the importance of bringing providing useful information on city conferences to Belfast and the ‘The AMHEC Conference is one of the tours, hotel room deals, sponsorship support available from BVCB. most prestigious in the third level contacts and local musicians and education sector and Stranmillis staff very valuable promotional booklets ‘My colleague, Norman Halliday, who look forward to welcoming the for every conference delegate. The is Director of Corporate Services at Association’s members to the College assistance has been refreshing, in the College, is a founder member next year. Key business matters that the attitude from BVCB staff has and enthusiastic supporter of the discussed at previous conferences has been ‘what can we do for you’ which Association of Managers in Higher included tuition fees, cost effective gives me great confidence that a Education and Colleges (AMHEC). -

Annual Report and Accounts 2007/08 the BBC Executive’S Review and Assessment 07 08

PART TWO: Annual Report and Accounts 2007/08 The BBC Executive’s review and assessment 07 08 Director- General ’s introduction 01 About the BBC 02 BBC & me 04 BBC Executive Board 24 BBC at a glance 26 Review of services Future Media & Technology 29 Vision 32 Audio & Music 38 Journalism 44 Commercial activities 52 Engaging with audiences 54 ...quality programming that informs Performance us, educates us and more often BBC People 58 than not, entertains us. These three Operations 62 Statements of Programme Policy tenets are as important today as commitments 2007/08 70 when they were first uttered around Finance 80 years ago. Financial overview 82 Governance and financial statements 86 Getting in touch with the BBC 148 Other information Inside back cover THE DIRECTOR -GENERAL 01 WELCOME When I wrote to you a year ago, our award- Despite these difficulties, the BBC has had a downloads and streams. And it’s still growing. winning Gaza correspondent Alan Johnston year of outstanding creative renewal. From There is no evidence that it is impacting was still missing. We didn’t know if we would Cranford to Sacred Music to Gavin and Stacey, our linear television and radio ratings which ever see him again. And then, what we’d all television has lived up to our aim – to delight remain very strong. been hoping, working and praying for: Alan’s audiences. And we have seen the nation share tired but smiling face as he was led to freedom. some of the events that unite us all – from the With Freesat now launched, complementing Concert for Diana to Wales’ triumph at the Six our popular Freeview service, it’s clear But within a few days, we had fresh problems Nations Rugby championship. -

7 to 13 July 26 May to 1 June

26 May to 1 June 7 to 13 July THE OLYMPIC TORCH RELAY CHAPTER 2 – 26 MAY TO 1 JUNE Day 9 it was the turn of rural Wales, with the Flame travelling through the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park and shining on Oystermouth Castle and Kidwelly Castle, setting for the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Torchbearers ran, grinned, waved, laughed and cried as they were greeted with frenetic flag-waving, car horns, wolf whistles and lively celebration. For good measure, the council in Carmarthen Wales – the land of castles and coastlines, dragons even arranged a giant trampoline to feed the carnival atmosphere. and daffodils, history, poetry, coal mines, choirs, ‘Didn’t we have a lovely time the day we went to Bangor?’ The rugby and railways – became from 26 May to 29 words of the 1979 hit single matched the sentiment of crowds who May the guardian of the London 2012 Olympic witnessed the Flame progress on a cliff-top railway in Aberystwyth Flame. Week 2 action started in Cardiff, fittingly in and on the Ffestiniog Railway steam train. The itinerary took in the hands of a Time Lord: actor Matt Smith, who plays Aberystwyth Castle, the Gorsedd Stones and Caernarfon Castle, Dr Who. The Relay evoked passionate enthusiasm recalling Prince Charles’s investiture as Prince of Wales in 1969. A as it passed through the South Wales Valleys and great day was concluded with theatrical gravitas by Bryn Terfel. then turned west to the sea, returning to mid and More adventure came the next day, as the Flame sped across North Wales and back into northwest England. -

Inquiry Into Medical Recruitment: Consultation Responses

------------------------ Public Document Pack ------------------------ Agenda Supplement - Health, Social Care and Sport Committee Meeting Venue: For further information contact: Committee Room 2 - Senedd Sarah Beasley Meeting date: 1 December 2016 Committee Clerk Meeting time: 09.15 0300 200 6565 [email protected] Please note the documents below are in addition to those published in the main Agenda and Reports pack for this Meeting - Inquiry into medical recruitment: Consultation Responses Inquiry into medical recruitment - consultation responses (Pages 1 - 144) Attached Documents: Cover contents MR 01 Phil Jones MR 02 Dr Adam Dallmann MR 03 Dr Geraint Morris MR 04 Andrew Davies MR 05 Royal College of Nursing Wales MR 06 Wales Deanery MR 07 Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh MR 08 Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health MR 09 Royal College of General Practitioners MR 10 Age Cymru MR 11 Dr Kate Gower Thomas BSc, MB BCh, FRCR MR 12 Aneurin Bevan University Health Board MR 13 Cardiff University School of Medicine MR 14 Royal College of Physicians MR 14 Royal College of Physicians Annex 1 MR 15 Royal College of Emergency Medicine Wales MR 16 Awen Iorwerth (Welsh only) MR 16 Awen Iorwerth (Courtesy Translation) MR 17 Public Health Wales MR 18 Royal Pharmaceutical Society MR 19 Bliss MR 20 British Medical Association (Wales) MR 21 Welsh NHS Confederation and NHS Wales Employers MR 22 Royal College of Psychiatrists Endsheet Agenda Item 11.1 Health, Social Care and Sport Committee Inquiry into medical recruitment November 2016 National Assembly for Wales Health, Social Care and Sport Committee Pack Page 1 The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. -

2 BBC Children in Need: the Best Bits 3 We Beat the All Blacks 4 Gower 5 Coming Home: Gethin Jones 6 Scrum V Live: Edinburgh V Ospreys 7 Pobol Y Cwm

Week/Wythnos 47 November/Tachwedd 17-23, 2012 Pages/Tudalennau: 2 BBC Children in Need: the Best Bits 3 We Beat The All Blacks 4 Gower 5 Coming Home: Gethin Jones 6 Scrum V Live: Edinburgh v Ospreys 7 Pobol y Cwm Places of interest: Anglesey 2 Barry 5 Cardiff 2 Gower 4 Llanelli 3 Pontyberem 5 Swansea 4, 6 Tonypandy 2 Follow us on Twitter to keep up with all the latest news from BBC Cymru Wales @BBCWalesPress Dilynwch ni ar Twitter am y newyddion diweddaraf gan BBC Cymru Wales @BBCWalesPress Pictures are available at www.bbcpictures.com / Lluniau ar gael yn www.bbcpictures.com NOTE TO EDITORS: All details correct at time of going to press, but programmes are liable to change. Please check with BBC Cymru Wales Communications before publishing. NODYN I OLYGYDDION: Mae’r manylion hyn yn gywir wrth fynd i’r wasg, ond mae rhaglenni yn gallu newid. Cyn cyhoeddi gwybodaeth, cysylltwch â’r Adran Gyfathrebu. BBC CHILDREN IN NEED: THE BEST BITS Saturday, November 17, BBC One Wales, 5.30pm bbc.co.uk/pudsey Welsh television personality Gethin Jones will look back at the best bits of this year’s BBC Children in Need appeal in Wales, with a highlights programme on BBC One Wales. Highlights include a performance from Tonypandy’s own West End star Sophie Evans, who will sing with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales. Sophie will perform songs including Over the Rainbow from The Wizard of Oz and Good Morning Baltimore from the musical Hairspray. The Orchestra and Sophie Evans will be joined by Côr Ieuenctid Môn (Anglesey Youth Choir), and a choir of school children from Cardiff and Tonypandy - who will link up with choirs from around the UK for a special performance. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 165 13 September 2010 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 165 13 September 2010 Contents Introduction 4 Note to Broadcasters Broadcasting Code changes: Section Ten of the Code 5 Standards cases In Breach The Jon Gaunt Show Talksport Radio, 10 October 2008 7 The Jon Gaunt Show Talksport Radio, April 2006 16 The Rundown ABS-CBN News Channel, 18 June 2010, 18:00 Balitang America ABS-CBN News Channel, 18 June 2010, 19:00 22 The Sports Bar Gold (Birmingham), 28 April 2010, 18:00 27 Apne Sitaray Venus TV, 26 May, 20:00 30 Bang Babes Tease Me, 23 July 2010, 21:45 to 22:30 Bang Babes Tease Me, 31 July 2010, 01:40 to 02:15 Bang Babes Tease Me, 6 August 2010, 22:00 to 22:25 and 00:00 to 00:45 33 Early Bird Tease Me TV (Freeview) 25 July 2010, 07:25 to 07:45 39 Resolved The Drive Time Show Buzz Asia, 5 July 2010, 16:00 42 Not in Breach An Inconvenient Truth Channel 4, 4 April 2009 21:20 (6 April 2009 on S4C) 44 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 165 13 September 2010 Advertising Scheduling cases In Breach Advertising minutage ESPN, ESPN Classic Sport UK, ESPN America, various dates between 3 and 15 June 2010, various times 56 Advertising minutage Wedding TV Asia, 3 May 2010, 20:00 58 Fairness & Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Miss Shamima Hussain Detailed Story, Channel S, 22 June 2009 59 Other programmes not in breach 64 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 165 13 September 2010 Introduction The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. -

Ysgol Evan James - Yr Awr Ddaear Medal I Eirlys

MAI 2012 Rhif 267 tafodtafod eelláiái Pris 80c Ysgol Evan James - Yr Awr Ddaear Medal i Eirlys Yn Eisteddfod Genedlaeth y Fro ym mis Awst cyflwynir Medal Goffa Syr T H Parry-Williams i Eirlys Britton o Gaerdydd. Mae Eirlys yn derbyn y Fedal am ei Cafwyd noson lwyddiannus i nodi’r Awr Ddaear. Nos Sadwrn Mawrth 31ain. gwaith diflino yn ardal Pontypridd am cynhaliwyd gweithgareddau yn Ysgol Gynradd Evan James ac yna ar yr iard bu disgyblion, rhieni, staff ac aelodau o’r gymuned yn cynnwys Maer Pontypridd, y gyfnod o dros ddeng mlynedd ar hugain. Cynghorydd Steve Carter, yn cyfri i lawr i un cyn diffodd goleuadau’r ysgol. Cariodd Yn wreiddiol o’r brifddinas, roedd Eirlys yn un o ddisgyblion cyntaf Ysgol pawb lusernau neu ganhwyllau dan gyfarwyddyd Heddlu’r Gymuned wrth gerdded Rhydfelen, Pontypridd, cyn graddio o’r iard draw i Barc Ynysangharad a daeth y noson i ben trwy ganu “Hen Wlad Fy mewn Drama yng Ngholeg y Drindod, Nhadau” yn ymyl cofgolofn Evan a James James yn y parc. Daeth gohebydd Caerfyrddin. Bu’n athrawes egnïol a newyddion BBC Radio Cymru Alun Thomas sy’n byw ym Mhontypridd i ymuno gyda ni ac ‘roedd yn braf clywed cymaint o leisiau gwahanol yn ei adroddiad ar hynod ddylanwadol yn Ysgol Heol y raglen y “Post Cyntaf”. Diolch eto i Emily Frowen am drefnu’r digwyddiad a gallwch Celyn ger Pontypridd, cyn ymuno â chast Pobol y Cwm, fel Beth Leyshon, weld uchafbwyntiau’r noson ar wefan ‘You Tube’ - http://www.youtube.com/watch? am nifer o flynyddoedd. -

EVENTS PORTFOLIO LEADERSHIP, MOTIVATIONAL, KEYNOTE & AFTER-DINNER SPEAKERS Triumph HOW CAN YOU DEFY YOUR LIMITS to TRIUMPH?

EVENTS PORTFOLIO LEADERSHIP, MOTIVATIONAL, KEYNOTE & AFTER-DINNER SPEAKERS triumph HOW CAN YOU DEFY YOUR LIMITS TO TRIUMPH? DEFY YOUR LIMITS Sir Bradley Wiggins CBE Britain’s Most Decorated Olympian HOW DO YOU MAINTAIN PEAK OVER 20 YEARS PERFORMANCE FOR OVER 20 YEARS? peak performance Dame Katherine Grainger DBE Britain’s Most Decorated Female Olympian tactics TEAM VICTORY IS STRATEGY WITHOUT TACTICS THE SLOWEST ROUTE TO TEAM VICTORY? Andrew Flintoff MBE Broadcaster and Cricketing Legend mindset and self-belief mindset BREAKING THE BARRIERS OF ADVERSITY ARE MINDSET AND SELF-BELIEF THE KEY TO SUCCESS AND BREAKING THE BARRIERS OF ADVERSITY ON AND OFF THE PITCH? Alex Scott MBE Presenter and Sports Pundit WHAT ROLE DOES family base strong A STRONG FAMILY BASE PLAY BOTH ON AND OFF THE PITCH? Harry and Jamie Redknapp ON AND OFF THE PITCH Football Icons, Father and Son Duo CONSISTENT SUCCESS collaboration and collective intelligence and collective collaboration DOES OPEN COLLABORATION AND COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE LEAD TO CONSISTENT SUCCESS? Sir Matthew Pinsent CBE Broadcaster and Gold Medal Winning Rower WHAT DIFFERENCES GROWTH CULTURE AND MINDSET ADVANTAGE CAN GROWTH CULTURE performance AND MINDSET ADVANTAGE MAKE TO PERFORMANCE? Matthew Syed Journalist, Author & Broadcaster HOW TO BECOME BRITAIN’S YOUNGEST EVER EUROPEAN professional ever tour youngest TOUR PROFESSIONAL TURNED LEADING GOLFTV PRESENTER? GOLFTV PRESENTER Henni Zuël GOLFTV Presenter and Former Ladies European Tour Professional ACHIEVE YOUR ‘IMPOSSIBLE DREAM’ organisational harmony,