1 of 21 Revealing Nakedness and Concealing Homosexual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminist Sexual Ethics Project

Feminist Sexual Ethics Project Same-Sex Marriage Gail Labovitz Senior Research Analyst, Feminist Sexual Ethics Project There are several rabbinic passages which take up, or very likely take up, the subject of same-sex marital unions – always negatively. In each case, homosexual marriage (particularly male homosexual marriage) is rhetorically stigmatized as the practice of non-Jewish (or pre-Israelite) societies, and is presented as an outstanding marker of the depravity of those societies; homosexual marriage is thus clearly associated with the Other. The first three of the four rabbinic texts presented here also associate homosexual marriage with bestiality. These texts also employ a rhetoric of fear: societal recognition of such homosexual relationships will bring upon that society extreme forms of Divine punishment – the destruction of the generation of the Flood, the utter defeat of the Egyptians at the Exodus, the wiping out of native Canaanite peoples in favor of the Israelites. The earliest source on this topic is in the tannaitic midrash to the book of Leviticus. Like a number of passages in Leviticus, including chapter 18 to which it is a commentary, the midrashic passage links sexual sin and idolatry to the Egyptians (whom the Israelites defeated in the Exodus) and the Canaanites (whom the Israelites will displace when they come into their land). The idea that among the sins of these peoples was the recognition of same-sex marriages is not found in the biblical text, but is read in by the rabbis: Sifra Acharei Mot, parashah 9:8 “According to the doings of the Land of Egypt…and the doings of the Land of Canaan…you shall not do” (Leviticus 18:3): Can it be (that it means) don’t build buildings, and don’t plant plantings? Thus it (the verse) teaches (further), “And you shall not walk in their statutes.” I say (that the prohibition of the verse applies) only to (their) statutes – the statutes which are theirs and their fathers and their fathers’ fathers. -

Acharei Mot (After the Death)

An Introduction to the Parashat HaShavuah (Weekly Torah Portion) Understanding the Torah From a Thematic Perspective Acharei Mot (After the Death) By Tony Robinson Copyright © 2003 (5764) by Tony Robinson, Restoration of Torah Ministries. All rights reserved. —The Family House of Study— Examining the Parashat HaShavuah by Thematic Analysis Welcome to Mishpachah Beit Midrash, the Family House of Study. Each Shabbat1 we gather in our home and study the Scriptures, specifically the Torah.2 It’s a fun time of receiving revelation from the Ruach HaKodesh3. Everyone joins in—adults and children—as we follow the Parashat HaShavuah4 schedule. We devote ourselves to studying the Torah because the Torah is the foundation for all of Scripture. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the Torah will help us more fully understand the rest of the Tanakh5 and the Brit Chadasha.6 Furthermore, as Yeshua stated Himself, the Torah teaches about Him. So we study the Torah in order to be drawn closer to Yeshua, the goal of the Torah. As believers in the Messiah we have discovered the richness of the wisdom of the sages of Israel. These men, who devoted themselves to the study of the Torah, have left us a rich heritage. Part of that heritage is a unique method of learning and interpreting the Scriptures. It’s called thematic analysis. In thematic analysis we search for the underlying theme/topic of each passage of Scripture. By studying Scriptures related by a common theme, line upon line and precept upon precept, the Scriptures open up to us in a unique manner that is clearly inspired by the Ruach HaKodesh. -

1 PARASHAH: Acharei Mot (After the Death) ADDRESS: Vayikra

PARASHAH: Acharei Mot (After the death) ADDRESS: Vayikra (Leviticus) 16:1-18:30 READING DATE: Shabbat AUTHOR: Torah Teacher Ariel ben-Lyman *Updated: March 20, 2007 (Note: all quotations are taken from the Complete Jewish Bible, translation by David H. Stern, Jewish New Testament Publications, Inc., unless otherwise noted) Let’s begin with the opening blessing for the Torah: “Baruch atah YHVH, Eloheynu, Melech ha-‘Olam, asher bachar banu m’kol ha-amim, v’natan lanu eht Torah-to. Baruch atah YHVH, noteyn ha-Torah. Ameyn." (Blessed are you, O’ LORD, our God, King of the Universe, you have selected us from among all the peoples, and have given us your Torah. Blessed are you, LORD, giver of the Torah. Ameyn.) Welcome to Parashat Acharei Mot. This particular commentary will represent the longest, most comprehensive article on the weekly portions that I have written to date. Be prepared for a long read! The following topics will be examined: • Kippur • Apologetics Part One • Apologetics Part Two • Yeshua’s Bloody Sacrifice • There’s Power in the Blood! • Do the Torah • Conclusions This particular parashah contains within it some of the single most impacting verses in the Torah. In theological studies, we call these passages "chair passages" as they have the power to change an entire theological argument, like a judge passing a sentence. In other words, sometimes a single passage can decide which direction in the proverbial fork in the road we should embark down! A significant quote from my opening teachings on Leviticus is surely in order before we get too far: Kippur 1 God's system of animal sacrifices, with their ability to cleanse or “wash” the flesh, was never intended to be a permanent one. -

Parashat Acharei Mot-Kedoshim

In the Bible there are other similar verses with the same meaning, for e idea is that nothing can break through these boundaries, this is a Being a Good A Very Rich Torah Portion example: Can’t I Just be a Good Person? legalistic approach. In this portion we also learn about the concept of holiness. e following One of the questions that always arises in every religious discussion is the e second way is to understand that life is the goal behind them. God Person is Only famous saying appears in our parasha: “I gave them my decrees and made known to them my laws, by following: If there's a person who does good, who seeks to help people, isn't presents us with the formula for a good, healthy, ecient, and correct life. If which the person who obeys them will live.” - Ezekiel 20:11 that enough? e answer is simple - he only fullls half of the work. Half of the Job “…Be holy because I, the Lord your God, am holy.” - Leviticus a person lives according to the way God presents, he will be considered a [NIV] good person. 19:2b [NIV] He keeps the laws, but what about the decrees that sanctify people and bring them closer to God? You cannot separate the two, the decrees and Parashat Today, I want to discuss two questions: What are the decrees and laws that If there are commandments or situations that clash with morality, courtesy, laws go together. Acharei Mot-Kedoshim As a result of this holy requirement, we have a rather immense collection of we are to keep and obey? Second, what does it truly meant to live and abide life, or the value of life. -

Source Sheet Israel & Achrei Mot Leviticus 18:24-28 Do

Achrei Mot 2020: Source Sheet Israel & Achrei Mot Leviticus 18:24-28 Do not defile yourselves in any of those ways, for it is by such that the nations that I am casting out before you defiled themselves. Thus the land became defiled; and I called it to account for its iniquity, and the land spewed out its inhabitants. But you must keep My laws and My rules, and you must not do any of those abhorrent things, neither the citizen nor the stranger who resides among you; for all those abhorrent things were done by the people who were in the land before you, and the land became defiled. So let not the land spew you out for defiling it, as it spewed out the nation that came before you. All who do any of those abhorrent things—such persons shall be cut off from their people. THEORY 1: Holiness is a byproduct of human behavior - the people are holy, therefore the land is: Menachem Kellner: Maimonides Confrontation with Mysticism According to [Maimonides'] view, holiness cannot be characterized as [existential] and essentialist. Holy places, persons, times, and objects are in no objective way distinct from profane places, persons, times, and objects. Holiness is the name given to a certain class of people, objects, times, and places which the Torah marks off. According to this view holiness is a status, NOT a quality of existence. It is a challenge, not a given... Yishayahu Leibowitz: Judaism, Human Values, and the Jewish State The land of Israel is the Holy Land and the Temple Mount is a holy place only by virtue of the Mitzvot linked to these locations. -

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5782 – 5784

Calendar of Torah and Haftarah Readings 5782 – 5784 2021 – 2024 Notes: The Calendar of Torah readings follows a triennial cycle whereby in the first year of the cycle the reading is selected from the first part of the parashah, in the second year from the middle, and in the third year from the last part. Alternative selections are offered each Shabbat: a shorter reading (around twenty verses) and a longer one (around thirty verses). The readings are a guide and congregations may choose to read more or less from within that part of the parashah. On certain special Shabbatot, a special second (or exceptionally, third) scroll reading is read in addition to the week’s portion. Haftarah readings are chosen to parallel key elements in the section of the Torah being read and therefore vary from one year in the triennial cycle to the next. Some of the suggested haftarot are from taken from k’tuvim (Writings) rather than n’vi’ivm (Prophets). When this is the case the appropriate, adapted blessings can be found on page 245 of the RJ siddur, Seder Ha-t’fillot. This calendar follows the Biblical definition of the length of festivals. Outside Israel, Orthodox communities add a second day to some festivals and this means that for a few weeks their readings may be out of step with Reform/Liberal communities and all those in Israel. The anticipatory blessing for the new month and observance of Rosh Chodesh (with hallel and a second scroll reading) are given for the first day of the Hebrew month. -

When the Law Is Unjust: Reconciling Leviticus 18:22 with Being a Jew A

When the Law is Unjust: Reconciling Leviticus 18:22 with Being a Jew A few weeks ago, in the New York Times Sunday Review, there was a short column entitled “Justice at the Opera.” The column was about a talk given by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg at the Glimmerglass opera festival in Cooperstown N.Y. At the festival, Justice Ginsburg discussed an aria called “I Accept Their Verdict” from “Billy Budd,” the opera based on Herman Melville’s novella. Budd is a sailor who is sentenced to death after killing an officer on his ship who had falsely accused him of organizing a mutiny. The aria is sung by CaptainVere who believes he must uphold the sentence as lawful since he must follow the letter of the law. Justice Ginsburg noted that Melville based the character of Vere on his own father- in-law, a Massachusetts judge who had ordered that an escaped slave be returned to his owner. The judge, Ginsburg said, opposed slavery but was obliged by his oath to uphold the law. Justice Ginsburg was discussing this in the context of, as she put it” the “conflict between law and justice.” 1 A member of the audience asked Justice Ginsburg whether the Supreme Court was either art or theater. “It’s both,” she responded, “with a healthy dose of real life mixed in.” This story and Justice Ginsburg’s comments about the conflict between law and justice helped me in thinking about how to approach my d’var this afternoon about sentence 22 in Leviticus18 that we read today. -

A Text-Critical Analysis of the Lamentations Manuscripts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository AText-criticalAnalysisoftheLamentationsManuscripts fromQumran(3QLam,4QLam,5QLam aand5QLam b) EstablishingthecontentofanOldTestamentbookaccordingtoits textualwitnessesamongtheDeadSeascrolls by GideonR.Kotzé DissertationpresentedinfulfilmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeDoctorofTheology(Old Testament)attheUniversityofStellenbosch Promoters: Prof.LouisJonker FacultyofTheology DiscplineGroupOldandNewTestament Prof.JohannCook FacultyofArtsandSocialSciences DeptofAncientStudies March2011 Declaration Bysubmittingthisdissertationelectronically, I declarethattheentirety ofthework contained thereinismyown,originalwork, thatIamthesoleauthorthereof(savetotheextentexplicitly otherwisestated),thatreproductionandpublicationthereofbyStellenboschUniversitywillnot infringeanythirdpartyrightsandthatIhavenotpreviouslyinitsentiretyorinpartsubmittedit forobtaininganyqualification. Date:15February2011 Copyright©2011StellenboschUniversity Allrightsreserved ii Summary This study takes as its point of departure the contributions of the Dead Sea scrolls to the disciplineofOldTestamenttextualcriticism.Itdealswithaparticularapproachtothisdiscipline and its application to the four Lamentations manuscripts from Qumran (3QLam, 4QLam, 5QLam aand5QLam b).TheapproachtoOldTestamenttextualcriticismfollowedinthestudy treatstheQumranmanuscriptsofLamentations,theMasoretictextandtheancienttranslationsas witnessestothecontentofthebookandnotmerelyaswitnessestoearlierformsofitsHebrew -

Parashat Kedoshim

Parashat Kedoshim Leviticus 19:1–20:27 April 30, 2011 / 26 Nisan 5771 This week's commentary was written by Dr. Judith Hauptman, E. Billi Ivry Professor of Talmud and Rabbinic Culture, JTS. Kedoshim in Context Chapter 19 of Parashat Kedoshim contains some of the loftiest statements in the entire Torah. Consider, for example, "Love your neighbor as yourself" (verse 18) and "Light up the faces of the old" (verse 32). It is strange that this high-minded set of directives finds itself sandwiched between two chapters that focus on forbidden sexual liaisons: chapter 18 lists the bans and chapter 20 the punishments. The women forbidden to men on the list in chapter 18 include a mother, stepmother, sister, granddaughter, aunt, daughter-in-law, and so on. If we recognize that in a patriarchal society sexual relationships are more likely to be initiated by men than women, the sense of these verses is that men should not impose themselves on female relatives. It is difficult to imagine a scenario in which sex with one's granddaughter would be fully consensual. To this day, we speak in one breath of abortion following rape or incest, implying that both are acts against a woman's will. Later in the same chapter, we find a ban on giving one's seed to Molekh (verse 21), an act that would be against the child's will. It therefore stands to reason that the very next verse—"do not make a man lie with you as one lies with a woman"—is yet another instance of forced submission (verse 22). -

Parasha Emor May 1, 2021 Torah

Parasha Emor May 1, 2021 Torah: Leviticus 21:1-24:3 Haftarah: Ezekiel 44:15-31 Ketuvim Sh’lichim: 1Peter 2:4-10 Shabbat shalom mishpacha! Our parasha today is Emor, which means “speak.” 1 Then Adonai said to Moses, “Speak to the kohanim, the sons of Aaron, and say to them,..(etc.)” (Leviticus 21:1a TLV). Leviticus chapters 21 and 22 are directions for the kohanim, the priests. These mitzvot are all about their holiness, separating themselves for ADONAI from unclean things. It was also a very practical thing. A kohen who had become unclean could not serve and their purpose was to serve ADONAI in ministry to Israel. There are some of us in Messianic Judaism today who are kohanim, descendants of Aaron, but these mitzvot are not applicable to them because there is no established Levitical priesthood and no Temple in which to minister. Possibly one day some of our Messianic kohanim will minister in a future Temple. But for us today, all of us, kohen, Levite, Israelite and Gentile, the concept of separating ourselves from unclean things has spiritual application, although not the specific things in this parasha. We are called to be clean because we, as Yeshua’s followers, are kohanim. Each of us is called to be a priest before ADONAI under our High Priest Yeshua. That is our objective for today and we can establish it with just four Scriptures. ADONAI charged Israel as they were about to approach Mount Sinai by saying to Moses: 6 “So as for you, you will be to Me a kingdom of kohanim and a holy nation.’ These are the words which you are to speak to Bnei-Yisrael” (Exodus 19:6 TLV). -

Challenge 2014: Bible in a Year Week 5: Exodus 39 — Leviticus 18 (January 26 — February 1)

Challenge 2014: Bible in a Year Week 5: Exodus 39 — Leviticus 18 (January 26 — February 1) Summary: forbidding Aaron to grieve the loss of his two sons. Once again, a Exodus comes to a close with the making and consecrating reminder of the weight God places on his proper worship. of the priestly garments and then the official raising of the Tabernacle. All are washed and presented at the court of the Tabernacle and God's Chapters 11-15 enter into a series of cleanliness codes: what Glory Cloud descended into the Tabernacle. This cloud not only led to eat, what to wear, etc... It is here that the Kosher laws come from the people through the wilderness, more importantly, it was a symbol and it is from here that we will learn more about leprosy, nocturnal that the presence of God, though veiled because of man's sin, was discharges, and female cleansing after childbirth than any of us with them. When John will introduce his Gospel, he will intentionally probably wants to know. Yet, these were part of the life of the people use similar language to point out that Jesus is the greater Tabernacle of Israel (as they are still today) and God saw fit to address them. and the Greater Temple — no longer a symbol of God's presence with Chapter 16 deals with the Day of Atonement in detail and us, but God in the flesh in our presence (John 1:14). chapters 17-18 begin the Holiness Code, what it means (ethically) to In Genesis 2 we found God dwelling with man in perfect be set apart from the nations. -

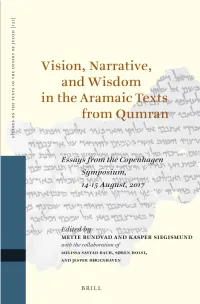

Dead Sea Scrolls—Criticism, Interpretation, Etc.—Congresses

Vision, Narrative, and Wisdom in the Aramaic Texts from Qumran Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah Edited by George J. Brooke Associate Editors Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar Jonathan Ben-Dov Alison Schofield volume 131 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/stdj Vision, Narrative, and Wisdom in the Aramaic Texts from Qumran Essays from the Copenhagen Symposium, 14–15 August, 2017 Edited by Mette Bundvad Kasper Siegismund With the collaboration of Melissa Sayyad Bach Søren Holst Jesper Høgenhaven LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: International Symposium on Vision, Narrative, and Wisdom in the Aramaic Texts from Qumran (2017 : Copenhagen, Denmark) | Bundvad, Mette, 1982– editor. | Siegismund, Kasper, editor. | Bach, Melissa Sayyad, contributor. | Holst, Søren, contributor. | Høgenhaven, Jesper, contributor. Title: Vision, narrative, and wisdom in the Aramaic texts from Qumran : essays from the Copenhagen Symposium, 14–15 August, 2017 / edited by Mette Bundvad, Kasper Siegismund ; with the collaboration of Melissa Sayyad Bach, Søren Holst, Jesper Høgenhaven. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2020] | Series: Studies on the texts of the desert of Judah, 0169-9962 ; volume 131 | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019029284 | ISBN 9789004413702 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004413733 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Dead Sea scrolls—Criticism, interpretation, etc.—Congresses. | Dead Sea scrolls—Relation to the Old Testament—Congresses. | Manuscripts, Aramaic—West Bank—Qumran Site—Congresses. Classification: LCC BM487 .I58 2017 | DDC 296.1/55—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019029284 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”.