(Bio)Sensors for Pesticides Detection Using Screen-Printed Electrodes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid IUPAC (2,4-dichlorophenoxy)acetic acid name 2,4-D Other hedonal names trinoxol Identifiers CAS [94-75-7] number SMILES OC(COC1=CC=C(Cl)C=C1Cl)=O ChemSpider 1441 ID Properties Molecular C H Cl O formula 8 6 2 3 Molar mass 221.04 g mol−1 Appearance white to yellow powder Melting point 140.5 °C (413.5 K) Boiling 160 °C (0.4 mm Hg) point Solubility in 900 mg/L (25 °C) water Related compounds Related 2,4,5-T, Dichlorprop compounds Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) is a common systemic herbicide used in the control of broadleaf weeds. It is the most widely used herbicide in the world, and the third most commonly used in North America.[1] 2,4-D is also an important synthetic auxin, often used in laboratories for plant research and as a supplement in plant cell culture media such as MS medium. History 2,4-D was developed during World War II by a British team at Rothamsted Experimental Station, under the leadership of Judah Hirsch Quastel, aiming to increase crop yields for a nation at war.[citation needed] When it was commercially released in 1946, it became the first successful selective herbicide and allowed for greatly enhanced weed control in wheat, maize (corn), rice, and similar cereal grass crop, because it only kills dicots, leaving behind monocots. Mechanism of herbicide action 2,4-D is a synthetic auxin, which is a class of plant growth regulators. -

WO 2012/125779 Al 20 September 2012 (20.09.2012) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/125779 Al 20 September 2012 (20.09.2012) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, A01N 43/90 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, (21) International Application Number: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, PCT/US20 12/029 153 MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (22) International Filing Date: OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, 15 March 2012 (15.03.2012) SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (30) Priority Data: GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, 61/453,202 16 March 201 1 (16.03.201 1) US UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US) : DOW DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, AGROSCIENCES LLC [US/US]; 9330 Zionsville Road, LV, MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, Indianapolis, IN 46268 (US). -

Solventless Formulation of Triclopyr Butoxyethyl

(19) & (11) EP 1 983 829 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A01N 43/40 (2006.01) A01N 25/30 (2006.01) 13.01.2010 Bulletin 2010/02 A01N 25/04 (2006.01) A01P 13/00 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 06837962.7 (86) International application number: PCT/US2006/044751 (22) Date of filing: 17.11.2006 (87) International publication number: WO 2007/094836 (23.08.2007 Gazette 2007/34) (54) SOLVENTLESS FORMULATION OF TRICLOPYR BUTOXYETHYL ESTER LÖSUNGSMITTELFREIE FORMULIERUNG VON TRICLOPYR-BUTOXYETHYLESTER FORMULE SANS SOLVANT D’ESTER DE BUTOXYETHYLE DU TRICYCLOPYR (84) Designated Contracting States: • POMPEO, Michael, P. DE ES FR GB IT Sumter, SC 29150 (US) (30) Priority: 15.02.2006 US 773417 P (74) Representative: Weiss, Wolfgang Weickmann & Weickmann (43) Date of publication of application: Patentanwälte 29.10.2008 Bulletin 2008/44 Postfach 86 08 20 81635 München (DE) (73) Proprietors: • Dow AgroSciences LLC (56) References cited: Indianapolis, WO-A-96/28027 WO-A-2004/093546 Indiana 46268-1054 (US) US-A1- 5 466 659 • Jensen, Jeffrey, Lee Brownsburg IN 46112 (US) • BOVEY RODNEY W ET AL: "Honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) control by synergistic (72) Inventors: action of clopyralid: Triclopyr mixtures" WEED • JENSEN, Jeffrey, Lee SCIENCE, vol. 40, no. 4, 1992, pages 563-567, Brownsburg, IN 46112 (US) XP009080681 ISSN: 0043-1745 • KLINE, William, N., III • BEBAWI F F ET AL: "Impact of foliar herbicides Duluth, GA 30096 (US) on pod and seed behaviour of rust-infected • BURCH, Patrick, L. rubber vine (Cryptostegia grandiflora) plants" Christiansburg, VA 24073 (US) PLANT PROTECTION QUARTERLY, vol. -

162 Part 175—Indirect Food Addi

§ 174.6 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–19 Edition) (c) The existence in this subchapter B Subpart B—Substances for Use Only as of a regulation prescribing safe condi- Components of Adhesives tions for the use of a substance as an Sec. article or component of articles that 175.105 Adhesives. contact food shall not be construed as 175.125 Pressure-sensitive adhesives. implying that such substance may be safely used as a direct additive in food. Subpart C—Substances for Use as (d) Substances that under conditions Components of Coatings of good manufacturing practice may be 175.210 Acrylate ester copolymer coating. safely used as components of articles 175.230 Hot-melt strippable food coatings. that contact food include the fol- 175.250 Paraffin (synthetic). lowing, subject to any prescribed limi- 175.260 Partial phosphoric acid esters of pol- yester resins. tations: 175.270 Poly(vinyl fluoride) resins. (1) Substances generally recognized 175.300 Resinous and polymeric coatings. as safe in or on food. 175.320 Resinous and polymeric coatings for (2) Substances generally recognized polyolefin films. as safe for their intended use in food 175.350 Vinyl acetate/crotonic acid copoly- mer. packaging. 175.360 Vinylidene chloride copolymer coat- (3) Substances used in accordance ings for nylon film. with a prior sanction or approval. 175.365 Vinylidene chloride copolymer coat- (4) Substances permitted for use by ings for polycarbonate film. 175.380 Xylene-formaldehyde resins con- regulations in this part and parts 175, densed with 4,4′-isopropylidenediphenol- 176, 177, 178 and § 179.45 of this chapter. -

Delayed Fluorescence Imaging of Photosynthesis Inhibitor and Heavy Metal Induced Stress in Potato

Cent. Eur. J. Biol. • 7(3) • 2012 • 531-541 DOI: 10.2478/s11535-012-0038-z Central European Journal of Biology Delayed fluorescence imaging of photosynthesis inhibitor and heavy metal induced stress in potato Research Article Jaka Razinger1,*, Luka Drinovec2, Maja Berden-Zrimec3 1Agricultural Institute of Slovenia, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia 2Aerosol d.o.o., 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia 3Institute of Physical Biology, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia Received 09 November 2011; Accepted 13 March 2012 Abstract: Early chemical-induced stress in Solanum tuberosum leaves was visualized using delayed fluorescence (DF) imaging. The ability to detect spatially heterogeneous responses of plant leaves exposed to several toxicants using delayed fluorescence was compared to prompt fluorescence (PF) imaging and the standard maximum fluorescence yield of PSII measurements (Fv/Fm). The toxicants used in the study were two photosynthesis inhibitors (herbicides), 100 μM methyl viologen (MV) and 140 μM diuron (DCMU), and two heavy metals, 100 μM cadmium and 100 μM copper. The exposure times were 5 and 72 h. Significant photosynthesis-inhibitor effects were already visualized after 5 h. In addition, a significant reduction in the DF/PF index was measured in DCMU- and MV-treated leaves after 5 h. In contrast, only DCMU-treated leaves exhibited a significant decrease in Fv/Fm after 5 h. All treatments resulted in a significant decrease in the DF/PF parameter after 72 h of exposure, when only MV and Cd treatment resulted in visible symptoms. Our study highlights the power of delayed fluorescence imaging. Abundant quantifiable spatial information was obtained with the instrumental setup. Delayed fluorescence imaging has been confirmed as a very responsive and useful technique for detecting stress induced by photosynthesis inhibitors or heavy metals. -

Evidence for Different Binding Sites on the 33-Kda Protein for DCMU, Atrazine and QB

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Volume 167, number 2 FEBS 1259 February 1984 Evidence for different binding sites on the 33-kDa protein for DCMU, atrazine and QB Chantal Astier, Alain Boussac and Anne-Lise Etienne Laboratoire de PhotosynthPse, CNRS, BP I, 91190 Gifsur-Yvette, France Received 21 November 1983; revised version received 4 January 1984 Two DCMU-resistant strains of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6714 were used to analyse the binding sites of DCMU, atrazine and QB. DCMU’-11~was DCMU and atrazine resistant; it presented an impaired electron flow and its 33-kDa protein was weakly attached to the membrane. DCMU’-IIB, derived from the former, simultaneously regained atrazine sensitivity, normal electron flow and a tight linkage of the 33-kDa protein to the membrane. This mutant shows that loss of DCMU binding does not necessarily affect the binding of either atrazine or QB. The role of the 33-kDa protein is discussed. Cyanobacteria Mutant Herbicide Photosynthesis Photosystem ZZ 1. INTRODUCTION that a specific attack of lysine residues resulted also in a partial release of inhibition by SN58132, Electron transfer on the acceptor side of a DCMU-type inhibitor [17]. Photosystem II occurs through a primary acceptor Radioactivity labelling experiments were used to QA [l] (a particular plastoquinone of the general demonstrate a competition between DCMU and pool [2] closely associated with the chlorophyll atrazine [6,18-201. A similar competition was pro- center), a secondary acceptor Qn [3] bound to its posed in [l l] between DCMU and QB. -

Interactions of Paraquat and Nitrodiphenylether Herbicides with the Chloroplast Photosynthetic Electron Transport in the Activation of Toxic Oxygen Species

INTERACTIONS OF PARAQUAT AND NITRODIPHENYLETHER HERBICIDES WITH THE CHLOROPLAST PHOTOSYNTHETIC ELECTRON TRANSPORT IN THE ACTIVATION OF TOXIC OXYGEN SPECIES by Brad Luther Upham Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Plant Physiology APPROVED: Kriton K. Hatzios, Chairman -----..------,,...-r---~---------J ohn L. Hess Joyce G. Foster Laurence D. Moore David M. Orcutt William E. Winner INTERACTIONS OF PARAQUAT AND.NITRODIPHENYLETHER HERBICIDES WITH THE PHOTOSYNTHETIC ELECTRON TRANSPORT IN THE ACTIVATION OF TOXIC OXYGEN SPECIES by Brad Luther Upham Kriton K. Hatzios, Chairman Plant Physiology (ABSTRACT) The interactions of paraquat (methylviologen) and diphenylether her- bicides with the Mehler reaction as investigated. Sera from two differ- ent rabbits (RSl & RS2) were examined for their patterns of inhibition of the photosynthetic electron transport (PET) system. Serum from RS2 was greatly hemolyzed. Fifty ul of RSI serum were required for 100% inhibi- tion of a 1120 --> methylviologen(MV)/02 reaction, whereas only 10 µl of a 1:10 dilution of RS2 were needed for 100% inhibition. The ~-globulin fraction from purified rabbit serum (RSl) did not inhibit PET, indicat- ing that the antibody fraction of the rabbit serum does not contain the inhibitor. It appears that the inhibitor is from the hemolyzed red blood cells. Rabbit sera, added to chloroplast preparations prior illu- mination, caused no inhibition of a 1120 --> MV/02 reaction while addi- tion of rabbit sera during illumination inhibited the 1120 --> MV/02 reaction within 1-3 s. Various Hill reactions were used to determine the site of inhibition. -

DCMU) Or Paraquat-Treated Euglena Gracilis Cells Erich F

Chlorophyll Photobleaching and Ethane Production in Dichlorophenyldimethylurea- (DCMU) or Paraquat-Treated Euglena gracilis Cells Erich F. Elstner and W. Osswald Institut für Botanik und Mikrobiologie, Technische Universität München, Arcisstr. 21, D-8000 München 2 Z. Naturforsch. 35 c, 129-135 (1980); received August 20/September 28, 1979 Chlorophyll Bleaching, Herbicides, Euglena gracilis, Ethane, Fat Oxidation Light dependent (35 Klux) chlorophyll bleaching in autotrophically grown Euglena gracilis cells at slightly acidic pH (6.5 —5.4) is stimulated by the photosystem II blockers DCMU and DBMIB (both 10~ 5 m) as well as by the autooxidizable photosystem I electron acceptor, paraquat (1 0 -3 m ). Chlorophyll photobleaching is accompanied by the formation of thiobarbituric acid — sensitive material (“malondialdehyde”) and ethane. Both chlorophyll photobleaching and light dependent ethane formation are partially prevented by higher concentrations (10~* m ) of the autooxidizable photosystem II electron acceptor DBMIB or by sodium bicarbonate (25 mM). In vitro studies with cell free extracts (homogenates) from E. gracilis suggest that a-linolenic acid oxidation by excited (reaction center II) chlorophyll represents the driving force for both ethane formation and chlorophyll bleaching. Ethane formation thus appears to be a sensitive and non-destructive “in vivo’’ marker for both restricted energy dissipation in photosystem II and, conditions yielding reactive oxygen species at the reducing side o f photosystem I. Introduction quent lipid attack and membrane destruction in the case of low potential photosystem I electron ac Chlorophyll bleaching is one of the characteristic ceptors as paraquat and other bipyridylium salts symptoms for plant diseases introduced by infec [4, 5, 9], tions, certain physical parameters or by chemicals. -

Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 2019 Theinternational Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) Was Established in 1980

The WHO Recommended Classi cation of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classi cation 2019 cation Hazard of Pesticides by and Guidelines to Classi The WHO Recommended Classi The WHO Recommended Classi cation of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classi cation 2019 The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 2019 TheInternational Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) was established in 1980. The overall objectives of the IPCS are to establish the scientific basis for assessment of the risk to human health and the environment from exposure to chemicals, through international peer review processes, as a prerequisite for the promotion of chemical safety, and to provide technical assistance in strengthening national capacities for the sound management of chemicals. This publication was developed in the IOMC context. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views or stated policies of individual IOMC Participating Organizations. The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC) was established in 1995 following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development to strengthen cooperation and increase international coordination in the field of chemical safety. The Participating Organizations are: FAO, ILO, UNDP, UNEP, UNIDO, UNITAR, WHO, World Bank and OECD. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the environment. WHO recommended classification of pesticides by hazard and guidelines to classification, 2019 edition ISBN 978-92-4-000566-2 (electronic version) ISBN 978-92-4-000567-9 (print version) ISSN 1684-1042 © World Health Organization 2020 Some rights reserved. -

Pesticide Residues : Maximum Residue Limits

THAI AGRICULTURAL STANDARD TAS 9002-2013 PESTICIDE RESIDUES : MAXIMUM RESIDUE LIMITS National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives ICS 67.040 ISBN UNOFFICAL TRANSLATION THAI AGRICULTURAL STANDARD TAS 9002-2013 PESTICIDE RESIDUES : MAXIMUM RESIDUE LIMITS National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives 50 Phaholyothin Road, Ladyao, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900 Telephone (662) 561 2277 Fascimile: (662) 561 3357 www.acfs.go.th Published in the Royal Gazette, Announcement and General Publication Volume 131, Special Section 32ง (Ngo), Dated 13 February B.E. 2557 (2014) (2) Technical Committee on the Elaboration of the Thai Agricultural Standard on Maximum Residue Limits for Pesticide 1. Mrs. Manthana Milne Chairperson Department of Agriculture 2. Mrs. Thanida Harintharanon Member Department of Livestock Development 3. Mrs. Kanokporn Atisook Member Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health 4. Mrs. Chuensuke Methakulawat Member Office of the Consumer Protection Board, The Prime Minister’s Office 5. Ms. Warunee Sensupa Member Food and Drug Administration, Ministry of Public Health 6. Mr. Thammanoon Kaewkhongkha Member Office of Agricultural Regulation, Department of Agriculture 7. Mr. Pisan Pongsapitch Member National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards 8. Ms. Wipa Thangnipon Member Office of Agricultural Production Science Research and Development, Department of Agriculture 9. Ms. Pojjanee Paniangvait Member Board of Trade of Thailand 10. Mr. Charoen Kaowsuksai Member Food Processing Industry Club, Federation of Thai Industries 11. Ms. Natchaya Chumsawat Member Thai Agro Business Association 12. Mr. Sinchai Swasdichai Member Thai Crop Protection Association 13. Mrs. Nuansri Tayaputch Member Expert on Method of Analysis 14. -

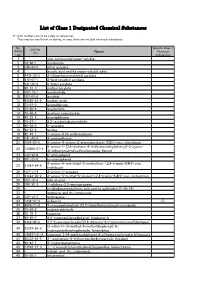

List of Class 1 Designated Chemical Substances

List of Class 1 Designated Chemical Substances *1:CAS numbers are to be solely as references. They may be insufficient or lacking, in case there are multiple chemical substances. No. Specific Class 1 CAS No. (PRTR Chemical (*1) Name Law) Substances 1 - zinc compounds(water-soluble) 2 79-06-1 acrylamide 3 140-88-5 ethyl acrylate 4 - acrylic acid and its water-soluble salts 5 2439-35-2 2-(dimethylamino)ethyl acrylate 6 818-61-1 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate 7 141-32-2 n-butyl acrylate 8 96-33-3 methyl acrylate 9 107-13-1 acrylonitrile 10 107-02-8 acrolein 11 26628-22-8 sodium azide 12 75-07-0 acetaldehyde 13 75-05-8 acetonitrile 14 75-86-5 acetone cyanohydrin 15 83-32-9 acenaphthene 16 78-67-1 2,2'-azobisisobutyronitrile 17 90-04-0 o-anisidine 18 62-53-3 aniline 19 82-45-1 1-amino-9,10-anthraquinone 20 141-43-5 2-aminoethanol 21 1698-60-8 5-amino-4-chloro-2-phenylpyridazin-3(2H)-one; chloridazon 5-amino-1-[2,6-dichloro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-cyano- 22 120068-37-3 4[(trifluoromethyl)sulfinyl]pyrazole; fipronil 23 123-30-8 p-aminophenol 24 591-27-5 m-aminophenol 4-amino-6-tert-butyl-3-methylthio-1,2,4-triazin-5(4H)-one; 25 21087-64-9 metribuzin 26 107-11-9 3-amino-1-propene 27 41394-05-2 4-amino-3-methyl-6-phenyl-1,2,4-triazin-5(4H)-one; metamitron 28 107-18-6 allyl alcohol 29 106-92-3 1-allyloxy-2,3-epoxypropane 30 - n-alkylbenzenesulfonic acid and its salts(alkyl C=10-14) 31 - antimony and its compounds 32 120-12-7 anthracene 33 1332-21-4 asbestos ○ 34 4098-71-9 3-isocyanatomethyl-3,5,5-trimethylcyclohexyl isocyanate 35 78-84-2 isobutyraldehyde -

20210311 IAEG AD-DSL V5.0 for Pdf.Xlsx

IAEGTM AD-DSL Release Version 4.1 12-30-2020 Authority: IAEG Identity: AD-DSL Version number: 4.1 Issue Date: 2020-12-30 Key Yellow shading indicates AD-DSL family group entries, which can be expanded to display a non-exhaustive list of secondary CAS numbers belonging to the family group Substance Identification Change Log IAEG Regulatory Date First Parent Group IAEG ID CAS EC Name Synonyms Revision Date ECHA ID Entry Type Criteria Added IAEG ID IAEG000001 1327-53-3 215-481-4 Diarsenic trioxide Arsenic trioxide R1;R2;D1 2015-03-17 2015-03-17 100.014.075 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000002 1303-28-2 215-116-9 Diarsenic pentaoxide Arsenic pentoxide; Arsenic oxide R1;R2;D1 2015-03-17 2015-03-17 100.013.743 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000003 15606-95-8 427-700-2 Triethyl arsenate R1;R2;D1 2015-03-17 2017-08-14 100.102.611 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000004 7778-39-4 231-901-9 Arsenic acid R1;R2;D1 2015-03-17 2015-03-17 100.029.001 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000005 3687-31-8 222-979-5 Trilead diarsenate R1;R2;D1 2015-03-17 2017-08-14 100.020.890 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000006 7778-44-1 231-904-5 Calcium arsenate R1;R2;D1 2015-03-17 2017-08-14 100.029.003 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000009 12006-15-4 234-484-1 Cadmium arsenide Tricadmium diarsenide R1;R2;D1 2017-08-14 2017-08-14 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000021 7440-41-7 231-150-7 Beryllium (Be) R2 2015-03-17 2019-01-24 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000022 1306-19-0 215-146-2 Cadmium oxide R1;R2;D1 2015-03-17 2017-08-14 100.013.770 Substance Direct Entry IAEG000023 10108-64-2 233-296-7 Cadmium