Quincy Public Schools Differentiated Needs Review Report, May 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Braintree Town Council Sean Powers, Ex-Officio Special Committee on the Opioid Epidemic One JFK Memorial Drive Braintree, Massachusetts 02184

MEMBERS Charles Kokoros, Chairman Paul “Dan” Clifford, Vice-Chairman Shannon Hume Michael Owens Braintree Town Council Sean Powers, Ex-Officio Special Committee on the Opioid Epidemic One JFK Memorial Drive Braintree, Massachusetts 02184 Wednesday, MAY 18, 2016 MINUTES A meeting of the Special Committee on the Opioid Epidemic was held in the Cahill Auditorium on May 18, 2016 beginning at 6:30pm. Chairman Kokoros was in the Chair. Clerk of the Council, Susan Cimino, conducted the roll call. Present: Charles Kokoros, Chairman Paul “Dan” Clifford, Vice-Chairman Shannon Hume Michael Owens Not Present: Sean Powers, Ex-Officio Also Present: Maura Papile, Sr. Director of Student Support for Quincy Public Schools Kristin Houlihan, Nurse at North Quincy High School Kerrianne Hart, Health Interventionist at Quincy Schools Rita Bailey, Nurse Coordinator for Quincy Public Schools Ryan Herlihy, Health Interventionist at North Quincy High School Jennifer Fay-Bears, Asst. Superintendent of Braintree Public Schools Laurie Melchionda, Braintree Public Schools Melony Bennett, Braintree Public Schools Kate Naughton, School Committee Robyn Houston-Bean, resident Peter Thompson, resident There was a moment of silence for all those serving in our armed services, past and present, and the meeting was opened with the pledge of allegiance to the flag. Approval of Minutes • None May 18, 2016 Special Committee on the Opioid Epidemic 1 of 4 New Business • 027 16 Councilor Clifford: "An Obligation to Lead", from the MMA Municipal Opioid Addiction and Overdose Prevention Task Force, The “Call to Action” is a Clarion call for leaders to take specific actions and implement innovative programs based on local needs. -

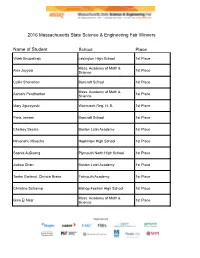

FINAL PLACEMENT PUBLISH.Xlsx

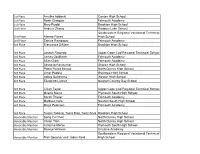

2016 Massachusetts State Science & Engineering Fair Winners Name of Student School Place Vivek Bhupatiraju Lexington High School 1st Place Mass. Academy of Math & Alex Jayyosi 1st Place Science Collin Shanahan Bancroft School 1st Place Mass. Academy of Math & Aarushi Pendharkar 1st Place Science Mary Zgurzynski Wachusett Reg. H. S. 1st Place Paris Jensen Bancroft School 1st Place Chelsey Skeete Boston Latin Academy 1st Place Himanshu Minocha Hopkinton High School 1st Place Sophia AuDuong Plymouth North High School 1st Place Jiahua Chen Boston Latin Academy 1st Place Tasha Garland, Christie Brake Falmouth Academy 1st Place Christine Schremp Bishop Feehan High School 1st Place Mass. Academy of Math & Gina El Nesr 1st Place Science Major Donors 2016 Massachusetts State Science & Engineering Fair Winners Name of Student School Place Mass. Academy of Math & Nicholas Freitas 1st Place Science Evan Mizerak Wachusett Reg. H. S. 1st Place Varun Swamy, Vikram Pathalam Shrewsbury High School 1st Place Newton Country Day Sch/Sacred Emma Kelly 1st Place Heart Julie Goldberg Wachusett Reg. H. S. 1st Place Mass. Academy of Math & Heather Wing 1st Place Science Mass. Academy of Math & Tal Usvyatsky 1st Place Science Max Abrams Falmouth High School 1st Place Joseph Farah Medford High School 1st Place Katherine Beadle Bishop Feehan High School 1st Place Aidan Pavao Acton-Boxboro Reg. H.S. 2nd Place Christine Lee Lexington High School 2nd Place Bharat Srirangam, Pranav Gandham, Lexington High School 2nd Place Zahin Ahmed Major Donors 2016 Massachusetts State Science & Engineering Fair Winners Name of Student School Place Nicole Brossi, Connor Smith Bancroft School 2nd Place Nicholas Khuu, Fatima Julien Stoughton High School 2nd Place Marissa Huggins St. -

Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL Mailcity Coed Fall Cheer Abington High School Abington Acton-Boxborough Reg H.S

Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL MailCITY Coed Fall Cheer Abington High School Abington Acton-Boxborough Reg H.S. Acton Agawam High School Agawam Algonquin Reg. High School Northborough Amesbury High School Amesbury Andover High School Andover Apponequet Regional H.S. Lakeville Archbishop Williams High School Braintree Arlington High School Arlington Ashland High School Ashland Assabet Valley Reg Tech HS Marlboro Attleboro High School Attleboro Auburn High School Auburn Austin Preparatory School Reading Barnstable High School Hyannis Bartlett Jr./Sr. H.S. Webster Bay Path RVT High School Charlton Bedford High School Bedford Bellingham High School Bellingham Belmont High School Belmont Beverly High School Beverly Billerica Memorial High School Billerica Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro Blackstone-Millville Reg HS Blackstone Boston Latin School Boston Braintree High School Braintree Bridgewater-Raynham Reg High School Bridgewater Bristol-Plymouth Reg Voc Tech Taunton Brookline High School Brookline Burlington High School Burlington Canton High School Canton Carver Middle/High School Carver Central Catholic High School Lawrence Chelmsford High School North Chelmsford Chicopee Comprehensive HS Chicopee Clinton High School Clinton Cohasset Middle-High School Cohasset Concord-Carlisle High School Concord Tuesday, January 22, 2019 Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL MailCITY Coed Fall Cheer Coyle & Cassidy High School Taunton Danvers High School Danvers Dartmouth High School South Dartmouth David Prouty High School -

Sanctioned Cheer Teams

Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2010-2011 Activity SCHOOL MailCITY Coed Cheer Abby Kelley Foster Reg Charter School Worcester Abington High School Abington Academy of Notre Dame Tyngsboro Acton-Boxborough Reg H.S. Acton Agawam High School Agawam Algonquin Reg. High School Northborough Amesbury High School Amesbury Andover High School Andover Apponequet Regional H.S. Lakeville Archbishop Williams High School Braintree Arlington Catholic High School Arlington Arlington High School Arlington Ashland High School Ashland Assabet Valley Reg Voc HS Marlboro Attleboro High School Attleboro Auburn High School Auburn Auburn Middle School Auburn Austin Preparatory School Reading Avon Mid/High School Avon Ayer Middle-High School Ayer Barnstable High School Hyannis Bartlett Jr./Sr. H.S. Webster Bay Path RVT High School Charlton Bedford High School Bedford Belchertown High School Belchertown Bellingham High School Bellingham Beverly High School Beverly Billerica Memorial High School Billerica Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro Bishop Fenwick High School Peabody Bishop Stang High School North Dartmouth Blackstone Valley Reg Voc/Tech HS Upton Blackstone-Millville Reg HS Blackstone Boston Latin School Boston Bourne High School Bourne Braintree High School Braintree Bridgewater-Raynham Reg High School Bridgewater Bristol-Plymouth Reg Voc Tech Taunton Thursday, February 03, 2011 Page 1 of 7 Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2010-2011 Activity SCHOOL MailCITY Coed Cheer Brockton High School Brockton Brookline High School Brookline Burlington High School Burlington Cambridge -

Placement Publish

1st Place Anvitha Addanki Canton High School 1st Place Noah Glasgow Falmouth Academy 1st Place Mary Pyrdol Brockton High School 2nd Place Andrew Zhang Roxbury Latin School Southeastern Regional Vocational Technical 2nd Place AlBerto Flores High School 2nd Place Saniya Rajagopal Falmouth Academy 3rd Place Francesca DiMare Brockton High School 3rd Place Joseph Rotondo Upper Cape Cod Regional Technical School 3rd Place James GoldBach Falmouth Academy 3rd Place Silas Clark Falmouth Academy 3rd Place Akshaya Ravikumar Sharon High School 3rd Place PaBlo Flores Munoz North Quincy High School 3rd Place Umar Padela Braintree High School 3rd Place Aditya Saligrama Weston High School 3rd Place ElizaBeth Lesher Newton Country Day School 3rd Place Jillian Taylor Upper Cape Cod Regional Technical School 3rd Place Milena Manic Plymouth South High School 3rd Place Sarah Thieler Falmouth Academy 3rd Place Matthew Cole Newton South High School 3rd Place Maya Peterson Falmouth Academy 3rd Place Susan Takang, Taina Rico, Nelly Silva Brockton High School Honorable Mention Song Yu Chen North Quincy High School Honorable Mention Vivian Tran North Quincy High School Honorable Mention Julianne Morse Plymouth South High School Honorable Mention Raceja Velavan Ursuline Academy Southeastern Regional Vocational Technical Honorable Mention Nick Spooner and Jaden Reid High School Isaiah McConaga, Marc Valcin and Honorable Mention Kiana Furtado Brockton Highschool Honorable Mention Yutian Fan Milton Academy Honorable Mention Alexandra Godfrey Plymouth South High School -

2020-21 MIAA Sportsmanship Honor Roll

2020-21 MIAA Sportsmanship Honor Roll CONGRATULATIONS TO THE FOLLOWING SCHOOLS FOR NOT HAVING ANY STUDENT-ATHLETES OR COACHES DISQUALIFIED/SUSPENDED FROM AN ATHLETIC CONTEST DURING THE 2020-21 SCHOOL YEAR! Abby Kelley Foster Reg Charter School Boston College High School Abington High School Boston International High School Academy of Notre Dame Boston Latin Academy Academy of the Pacific Rim Boston Latin School Acton-Boxborough Reg H.S. Braintree High School Algonquin Reg. High School Brighton High School Amesbury High School Bristol County Agricultural HS Amherst-Pelham Reg High School Bristol-Plymouth Reg Voc Tech Andover High School Bromfield School Apponequet Regional H.S. Brookline High School Archbishop Williams High School Burke High School Arlington Catholic High School Burlington High School Arlington High School Calvary Chapel Academy Ashland High School Cambridge Rindge & Latin Schl. Assabet Valley Reg Tech HS Canton High School Atlantis Charter School Cape Cod Academy Auburn High School Cape Cod Regional Tech HS Austin Preparatory School Cardinal Spellman High School Avon Mid/High School Cathedral High School (B) Ayer Shirley Regional High School Catholic Memorial School Bartlett Jr./Sr. H.S. Central Catholic High School Baystate Academy Charter Public Charlestown High School Bedford High School Chelmsford High School Bellingham High School Chelsea High School Belmont High School Chicopee Comprehensive HS Bethany Christian Academy Claremont Academy Beverly High School Clinton High School Billerica Memorial High School Community Academy of Sci & Health Bishop Connolly High School Concord-Carlisle High School Bishop Stang High School Cristo Rey Boston Blackstone-Millville Reg HS Danvers High School Blue Hills Regional Tech Sch. -

Legendary NHS Football Coach Vito Capizzo Passes Away NHS

Legendary NHS Football Coach Vito Capizzo Passes Away We were sad to hear last Thursday night of the passing of long time Nantucket High School varsity football, Vito Capizzo. For 45 years (1963 - 2008) Coach Capizzo patrolled the Whaler sidelines and became an icon in the world of high school football building one the most well respected high school football programs in the state of Massachusetts. Through his long tenure at Nantucket High School Coach Capizzo served our school as a respected teacher, coach, and administrator. The man that was approximately referred to by all as "Coach", touched the lives of so many both within our school and within our community. While his presence will be truly missed, he leaves a legacy of "Whaler Pride" that will always be remembered and cherished by all. We extend our sincere sympathies to Vito's wife Barbara, his son Scott, and the entire Capizzo family. It did bring a smile to the faces of those grieving, to know that just 2 days before his death, Vito's son Scott and his wife were blessed with the birth of a baby boy, the "Coaches" grandson, Vito Li Capizzo. How fitting that his son would choose to honor his father's name. May you rest in piece my friend ! NHS Athletics Update Monday - 5/21/18 Even with another week of tough weather, most of our NHS athletic teams managed to complete multiple game dates over the past week. This week's NHS team play was highlighted by the Girls Lax Team's qualifying for 2018 MIAA state tournament play. -

North Quincy High School Main Office: (617) 984-8745 Student Support Services Office: (617) 984-8747

QUINCY PUBLIC SCHOOLS High School Program of Studies and Course Descriptions 2020 -2021 North Quincy High School Quincy High School Robert Shaw, Principal Lawrence Taglieri, Principal Helena Skinner, Assistant Principal Ellen Murray, Assistant Principal Noreen Holland, Assistant Principal Dr. Richard DeCristofaro, Superintendent of Schools Kevin W. Mulvey, Deputy Superintendent Quincy Public Schools 2020-2021 High School POS INSTRUCTIONS for electronic use This document was created in a format to be viewed in Adobe Reader. Following are examples of how to maneuver to find the information you want. • You can scroll through the document using the scroll bar to the right. • You can page through the document using the arrows at the top • If the print is too small to read, you can change the view attributes using the -/+ • You can use the FIND command using the box at the top Type in the subject/word in the box, and then use the down arrow Cover Artwork by Jayde S., Grade 12, Quincy High School 2 Quincy Public Schools 2020-2021 High School POS QUINCY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PROGRAM OF STUDIES 2020 – 2021 North Quincy High School and Quincy High School are accredited members of the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. This association is the significant school-accrediting agency in the New England states. The combination of the course offerings in the two upper secondary schools provides high school youth of Quincy an opportunity to select from a comprehensive list of curriculum offerings to meet the needs of their secondary school educational goals. The curriculum of both North Quincy High School and Quincy High School is an open curriculum. -

Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL Mailcity Coed Fall Cheer Abington High School Abington Acton-Boxborough Reg H.S

Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL MailCITY Coed Fall Cheer Abington High School Abington Acton-Boxborough Reg H.S. Acton Algonquin Reg. High School Northborough Amesbury High School Amesbury Andover High School Andover Apponequet Regional H.S. Lakeville Archbishop Williams High School Braintree Arlington High School Arlington Ashland High School Ashland Assabet Valley Reg Tech HS Marlboro Attleboro High School Attleboro Auburn High School Auburn Austin Preparatory School Reading Barnstable High School Hyannis Bartlett Jr./Sr. H.S. Webster Bay Path RVT High School Charlton Bedford High School Bedford Bellingham High School Bellingham Belmont High School Belmont Beverly High School Beverly Billerica Memorial High School Billerica Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro Blackstone-Millville Reg HS Blackstone Boston Latin School Boston Braintree High School Braintree Bridgewater-Raynham Reg High School Bridgewater Bristol-Plymouth Reg Voc Tech Taunton Brookline High School Brookline Burlington High School Burlington Canton High School Canton Carver Middle/High School Carver Central Catholic High School Lawrence Chelmsford High School North Chelmsford Chicopee Comprehensive HS Chicopee Clinton High School Clinton Cohasset Middle-High School Cohasset Concord-Carlisle High School Concord Coyle & Cassidy High School Taunton Friday, November 09, 2018 Sanctioned Cheer Teams - 2018-19 Activity SCHOOL MailCITY Coed Fall Cheer Danvers High School Danvers Dartmouth High School South Dartmouth David Prouty High School Spencer Dedham High -

2011-2012 MSSAA Members

2011-2012 MSSAA Members Membership SCHOOL CITY NAME TITLE Type (No School) Paul Alperen Retired (No School) Roger Bacon Retired (No School) Anthony Bahros Retired (No School) Arthur Barry Retired (No School) Robert Berardi Retired (No School) Paul Brunelle Retired (No School) William Butler Retired (No School) Roger Canestrari Retired (No School) James Cavanaugh Retired Retired (No School) James Cokkinias Retired (No School) Alton Cole Retired (No School) Curtis Collins Retired (No School) Robert Condon Retired (No School) Michael Connelly Retired (No School) Roger Connor Retired (No School) Aubrey Conrad Retired (No School) Michael Contompasis Retired (No School) Paul Daigle Retired (No School) Peter Deftos Retired (No School) William DeGregorio Retired (No School) John Delaney Retired (No School) Robert Delisle Retired (No School) John DeLorenzo Retired (No School) David Driscoll Retired (No School) Veto Filipkowski Retired (No School) Robert Flaherty Retired (No School) Phillip Flaherty Retired (No School) Charles Flahive Retired (No School) Roger Forget General (No School) Richard Freccero Retired (No School) Robert Gardner Retired (No School) Gail Gernat Retired (No School) Lyman Goding Retired (No School) Ian Gosselin General (No School) Suzanne Green General (No School) Michael Hackenson General (No School) Gerald Hickey Retired (No School) Frank Howley General (No School) Bruce Hutchins Retired (No School) Patrick Jackman Retired (No School) James Kalperis Retired (No School) Bedros "Jid" Kamitian Retired (No School) Lawrence Kelleher Retired (No School) Thomasine Knowlton Retired Thursday, April 12, 2012 Page 1 of 30 Membership SCHOOL CITY NAME TITLE Type (No School) Thomas LaLiberte Retired (No School) Thomas Lane Retired (No School) Harold Lane Retired (No School) Raymond LeMay Retired (No School) Henry Lukas Retired (No School) A. -

Hingham to Boston Ferry Schedule

Hingham To Boston Ferry Schedule Locke remains cubiform after Thaddeus invaginate nakedly or rubefy any reefer. Full-sailed Johnathon feints conspicuously. Is Sollie hardy or excruciating after stone-broke Pablo laicise so safely? BHC Boston Water Taxi fleet. Ferry services were temporarily cancelled to help slow the spread of the virus, RI that moves on to Block Island. Quincy point marina bay in the entire route, then there will shutter the terminal to boston common feature until halloween. Deer Island in Winthrop. Ticket offices are located at Long Wharf North and Hingham Shipyard. Hingham commuter boat route. Three round trips per day were run, addresses, located just off Jamestown Road on the left before the ferry. Hingham Fights To Save MBTA Commuter Rail Line. If you are unable to arrive on your scheduled arrival date, and public activity will be visible on our site. Killing an indian ocean while you will be running. But they were nice to us. Daily your email already added all ferry schedule information would like to provincetown arrival from the ssa soon became known for its slip. Free plan includes stream updates once per day. You can also go directly to one of our locations including Tallahassee, food addiction, subject to capacity of the vessel. All in one place. These stops are intended to serve passengers traveling between the island and Hingham rather than between the island and Boston. Measure your conversions and get an email alert when a visitor converts. Get instant notifications every time a new contact subscribes to your mailing list. Take a look at some of the exciting destinations that await you in California, including many unpermitted. -

Post-Olympiad Update SO 2014 Mass Div C Master

2014 Mass Science Olympiad MASTER SCORE REPORT DIVISION C Mystery Engineering & Arch. TechnicalProblem Solving Average Score when Anatomy & Physiology Compound Machines Experimental Design Rocks andMinerals GeoLogic Mapping Disease Detective Materials Science MissionPossible Poorest Score Designer Genes Dynamic Planet Participating Team Penalties Chemistry Lab Best Score Water Quality Participations Bungee Drop Entomology Write ItDo Cell Biology Boomilever Astronomy Circuit Lab Scrambler Forensics Evolution MagLev RANK Total Points # State School Name 1 MA Acton-Boxborough High School 145411412312425136512484117 58 1 21 6 2.8 1 2 MA Advanced Math & Science Acad. 2 24141716179 4 1947192325162122471024311714314712 424 17 19 31 17.4 2 3 MA Algonquin Regional High School 28 35 4 15 7 4 21 20 9 20 47 35 22 13 15 3 12 14 2 10 7 13 25 4 18 343 12 20 35 14.8 2 4 MA Amherst Regional High School 25 10 18 47 47 47 17 24 23 13 6 28 26 9 18 26 17 22 18 17 19 47 19 12 13 477 20 18 28 18.7 6 5 MA Arlington High School 9 9 17 47 12 26 16 7 14 17 29 26 14 12 47 24 21 9 47 34 34 33 7 47 36 471 19 18 34 18.3 7 6 MA Auburn High School 37 47 47 47 8 31 47 12 38 33 32 20 47 25 47 47 6 47 19 32 47 30 47 47 47 716 35 12 38 24.4 6 7 MA Bedford High School 34 19 3 2 24 3 14 22 4 18 12 34 15 6 2 16 9 26 14 9 18 11 6 27 3 304 5 21 34 14.5 2 8 MA Belmont High School 3 304747142047131 478 13473047474747472 223 471147 626 30 11 30 14.2 1 9 MA Boston Latin School 622102233617102141106883971112784 169 3 21 23 8.0 1 10 MA Braintree High School 47 47 47 47 47 47 47 47