Would You Agree That Terence O Neill and /Or Brian Faulkner Failed As a Political Leader? Argue Your Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Previous Attempts to Bring Peace to Northern Ireland Have Failed. What Problems Need to Be Overcome So Devolution and Peace Can Succeed in Northern Ireland?

Previous attempts to bring peace to Northern Ireland have failed. What problems need to be overcome so devolution and peace can succeed in Northern Ireland? So what are the problems? Paramilitaries – Loyalist and Republican terrorists are fighting a war against each other. Unionist and Nationalist politicians find it hard to discuss peace when the other side is killing their people. Partition – Both sides want different things. Nationalists want a Free and independent Ireland. Unionists want Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK. British and Irish governments – There was a great deal of mistrust between Dublin and London until 1985. Distrust – Unionists/Protestants and Nationalists/Catholics do not trust each other. Economic and Social problems. Poor schooling, housing and amenities need investment. Who gets the investment first. High Unemployment is caused by lack of companies and businesses willing to invest in Northern Ireland whilst the Troubles continue. America was funding the IRA and Sinn Fein. Weapon decommissioning and the end of violence. The arrest and detainment of innocent Catholics. Orange Marches and RUC seen as offensive to Nationalists. Civil Rights. Different opinions amongst the Unionists and Nationalists. DUP vs UUP. Sinn Fein vs SDLP. Obstacles to Peace - Politics During the Troubles, the media reports of bombs and shootings gave people outside Northern Ireland the impression that Northern Ireland was a war zone. It seemed to have no normal life and no normal politics either. This was not the case. There were 'normal' political parties in Northern Ireland, and most people supported them. All the parties had views and policies relating to a wide range of 'normal' issues such as education, health care and housing. -

5.IRL Politics and Society in Northern Ireland |Sample Answer Would You Agree That Terence O'neill And/Or Brian Faulkner Failed As a Political Leader?

5.IRL Politics and Society in Northern Ireland | Sample answer Would you agree that Terence O’Neill and/or Brian Faulkner failed as a political leader? Argue your case. (2018) Brian Faulkner became Prime Minister of Northern Ireland in March 1971 after Chichester-Clarke’s resignation. During his time as Prime Minister the IRA intensified their campaign. In an effort to stem the violence, Faulkner introduced internment in April 1971. The policy was a disaster. It increased nationalist grievances and won support for the republican cause. After Bloody Sunday, 30th January 1972, the British government lost faith in Faulkner’s ability to restore order in Northern Ireland and introduced direct rule, suspending the Stormont Government. This essay aims to examine how Brian Faulkner failed as a political leader. Brian Faulkner was born in Co. Down in 1921. He was elected to Stormont as MP for East Down in 1949; he was appointed Minister for Health Affairs in 1959. Following the resignation of Lord Brookeborough as Prime Minister in 1963, Faulkner was seen as a likely candidate to succeed him. However, he lost out to Terence O’Neill. Faulkner served under O’Neill as Minister for Commerce and excelled in stimulating economic growth. Faulkner resigned from the cabinet in January 1969 in protest of O’Neill’s intention to reform local government, particularly the one man one vote. He finally became Prime Minister in March 1971. While his career ended in failure, Faulkner’s strengths saw him successfully manoeuvre between demands from Unionists and Nationalists. He worked efficiently to strike a balance between the demands of ordinary unionists and the demands of the British for concessions to nationalists. -

From Deference to Defiance: Popular Unionism and the Decline of Elite Accommodation in Northern Ireland

From Deference to Defiance: Popular Unionism and the Decline of Elite Accommodation in Northern Ireland Introduction On 29 November, 2003, The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), the party that had governed Northern Ireland from Partition in 1921 to the imposition of Direct Rule by Ted Heath in 1972, lost its primary position as the leading Unionist party in the N.I. Assembly to the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Reverend Ian Paisley. On 5 May, 2005, the electoral revolution was completed when the DUP trounced the UUP in the Westminster elections, netting twice the UUP's popular vote, ousting David Trimble and reducing the UUP to just one Westminster seat. In March, 2005, the Orange Order, which had helped to found the UUP exactly a century before, cut its links to this ailing party. What explains this political earthquake? The press and most Northern Ireland watchers place a large amount of stress on short-term policy shifts and events. The failure of the IRA to show 'final acts' of decommissioning of weapons is fingered as the main stumbling block which prevented a re-establishment of the Northern Ireland Assembly and, with it, the credibility of David Trimble and his pro-Agreement wing of the UUP. This was accompanied by a series of incidents which demonstrated that the IRA, while it my have given up on the ‘armed struggle’ against the security forces, was still involved in intelligence gathering, the violent suppression of its opponents and a range of sophisticated criminal activities culminating in the robbery of £26 million from the Northern Bank in Belfast in December 2004. -

New Prime Minister 1969

Author: Anne-Marie Ryan Curriculum links: Politics and society in Northern Ireland, 1949-1993 - civil rights movement RTÉ Archives, Online exhibition: Violence in Northern Ireland 1969 - New prime minister, 1969 Access the online exhibition here. Terence O’Neill resigned as leader of the Unionist Party and prime minister of Northern Ireland in April 1969. On 1 May 1969, O’Neill’s cousin, James Chichester- Clarke, was elected as leader of the Unionist Party and became prime minister. Activity 1 Watch the video clip ‘Chichester-Clarke, New Prime Minister’ (1969) and answer the following discussion questions: • Chichester-Clarke was elected by a margin of how many votes? What does this result tell you about the state of the Unionist Party in 1969? • In general, those who had supported Terence O’Neill voted for Chichester-Clarke and those who had opposed him voted for Brian Faulkner. What does this tell you about the type of prime minister Chichester-Clarke was likely to be? Activity 2 Listen to the clip, ‘Reaction from Derry on Chichester-Clarke’ where residents of the Catholic Bogside and Protestant Fountain Street areas of Derry give their views on the election of James Chichester-Clarke as prime minister of Northern Ireland. Make notes on their views in the boxes below: Catholics from the Bogside Author: Anne-Marie Ryan Protestants from Fountain Street Based on the views expressed by the people in this audio clip, do you think that James Chichester- Clarke will be an effective prime minister of Northern Ireland? Why/why not?. -

The Sunningdale Agreement and Power Sharing Executive, 1973

History Support Service Supporting Leaving Certificate History www.hist.ie Later Modern Ireland Topic 5, Politics and society in Northern Ireland, 1949-1993 Documents for case study: The Sunningdale Agreement and the power-sharing executive, 1973-1974 Contents Preface page 2 Introduction to the case study page 3 Biographical notes page 4 Glossary of key terms page 8 List of documents page 12 The documents page 13 This material is intended for educational/classroom use only and is not to be reproduced in any medium or forum without permission. Efforts have been made to trace and acknowledge copyright holders. In cases where a copyright has been inadvertently overlooked, the copyright holders are requested to contact the History Support Service administrator, Angela Thompson, at [email protected] ©2009 History Support Service, County Wexford Education Centre, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford. Ph. 353 53 923 9121, Fax 353 53 923 9132, Email [email protected], Website www.hist.ie PREFACE The topic, Politics and society in Northern Ireland, 1949-1993, is prescribed by the State Examinations Commission (SEC) for the documents-based study for the 2010 and 2011 Leaving Certificate examinations. The case studies for the topic are: • The Coleraine University controversy • The Sunningdale Agreement and the power-sharing executive, 1973-1974 • The Apprentice Boys of Derry The set of documents selected for each of the case studies, and presented herein, is varied in nature and represents varying points of view, enabling students to look at the case study from different perspectives. Each set of documents is accompanied by an introduction which gives an outline of the case study and the relevance of each of the documents to the different aspects of the case study. -

The Troubles in Northern Ireland in the Late 1960S

DEMOCRATIC AND POPULAR REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA MINISTARY OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNIVERLSITY OF ORAN ES- SENIA Faculty of Letters, Languages, & Arts Department Of Anglo- Saxon Languages, Section Of English Magister Dissertation in British Civilization The Troubles in Northern Ireland in the Late 1960s Presented by : Supervised by : Mrs. DARRAB. LAHOUARIA Dr. BOUHADIBA. ZOULIKHA The members of the Jury : Chairperson: Dr. Belmekki Belkacem Supervisor: Dr. Bouhadiba Zoulikha Examiner: Dr. Moulfi Leila Academic Year 2011-2012 E.D 2007-2008 THE TROUBLES IN NORTHERN IRELAND IN THE LATE 1960S CONTENTS Dedication ..................................................................................................................... I Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................II Abstract ........................................................................................................................III List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................IV List of Maps ..................................................................................................................V List of Tables ................................................................................................................VI General Introduction ...................................................................................................1 CHAPTER ONE: Ireland from the Norman Invasion to the -

NATIONAL ARCHIVES IRELAND Reference Code: 2002/8/77 Title: Statement by Brian Faulkner on His Election As Leader of the Ulste

TSCH/3: Central registry records Department of the Taoiseach NATIONAL ARCHIVES IRELAND Reference Code: 2002/8/77 Title: Statement by Brian Faulkner on his election as leader of the Ulster Unionist Party. Creation Date(s): 23 March, 1971 Level of description: Item Extent and medium: 3 pages Creator(s): Department of the Taoiseach Access Conditions: Open Copyright: National Archives, Ireland. May only be reproduced with the written permission of the Director of the National Archives. © National Archives, Ireland St atement by lvlr $ Brian Faulkner on his election as l eader of the Unionist Party 23 March, 1971 Gentlemen:- I'd like just to say a wor'd or two to you and then briefly, as I understand time is limited , I 'll answer a question or two but I ' m TSCH/3: Centralafraid registry recordsit will have to be brief. And I hope Departmentthat through of the you Taoiseach I am perhaps speaking to a l arger outside world. I regard it as my most important single aim to restore confidence to the entire co ~n unity in No rthern Ireland, because I am utterly convinced that without that r estoration of confidence all else i s futileo The keTnel of our immediate problems in Ulster is the l aw and order situation. Here we don 't need new principles, wh at we need are practical results on the ground, practical results in the elimi nation of terrorism, in the elimination of sabotage and in the ending of riots and disorders. The basic pri nc i ple must be t ha t the rule of law will operate in all parts of Northern Ireland, so that the security wh ich goes with the rule of law can be enjoyed quite l iterally by all our citizens. -

The Real Lessons of Ulster by Dean Godson

Issue 140, November 2007 The real lessons of Ulster by Dean Godson The Northern Ireland conflict is now fought over the lessons of the Troubles. One apparent lesson is that only extremists can make deals stick. But perhaps the real conclusion is that the late-colonial British did not properly study their own history Dean Godson is research director of Policy Exchange and a contributing editor to Prospect. His biography of David Trimble, Himself Alone, is published by HarperCollins Why should anyone still care about the Ulster Unionist party, the Orange Order or, for that matter, Northern Ireland itself? The UUP, the ruling party for the first half century of Northern Ireland's existence, from 1921 to 1972, is about as healthy as Ariel Sharon--nominally alive but, to all intents and purposes, a goner. The Orange Order seems destined to enter one of its extended periods of quiescence, such as it went through in the 19th century. Even the novelty of Ian Paisley's danse macabre with Martin McGuinness has attracted less attention in Britain than might have been expected. The reasons for this apparent indifference to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact by the Lagan aren't hard to fathom. Northern Ireland isn't news any more because the second IRA ceasefire is now a decade old. And many in Northern Ireland believed all along that mainland opinion only ever cared about the ending of full-scale violence. With vast amounts of British taxpayer and EU money still flooding into the place, Ulster seems to have reverted into its complacent, parochial, pre-Troubles self. -

Burroughs 1 the Republican Threat

Burroughs 1 The Republican Threat: How Protestant Anxieties and Republican Plotting Destabilized Northern Ireland By Kimberly Burroughs Advised by Professor Harland-Jacobs April 16, 2012 Burroughs 2 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Republican Conspiracy 5 Chapter 2: The Civil Rights Movement Begins 13 Chapter 3: A Turn to Mass Demonstration 20 Chapter 4: The Real Republican Threat 29 Chapter 5: Internment 41 Conclusion 51 Burroughs 3 I would like to thank Professor Jessica Harland-Jacobs for her invaluable guidance and support throughout this project. I would also like to thank my family for always encouraging me to pursue my passions. Burroughs 4 Introduction The British occupation of Ireland began in the twelfth century and persisted until 1921. Over eight hundred years of British rule, imperial policies segmented the island into distinct cultural regions. The residents of the northern Ulster province strongly identified with British culture (and Protestantism), while southern Irish Catholics, exploited economically by centuries of British rule, rejected the Empire. By the early twentieth century the regions had established imagined communities based on these opposing ideologies. Southern nationalists (frequently Catholic) increasingly agitated for Irish independence, while Northern Protestants desperately clung to union with Britain, fearing absorption into an alienating Catholic state. Tensions between Unionists (who wanted to remain within the British Empire) and Nationalists would prompt violence as these two communities, feeling intrinsically at odds with each other, clashed over the future of Ireland. In 1916 a small band of Irish nationalists in the city of Dublin launched an uprising now known as the Easter Rising. Aware of the high-likelihood of failure, the revolutionaries martyred themselves in an effort to galvanize Irish Nationalists into revolution. -

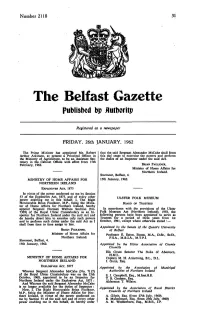

The Belfast Gazette Published Dp Flutboritp

Number 2118 31 The Belfast Gazette Published Dp flutboritp Registered as a newspaper FRIDAY, 26th JANUARY, 1962 The Prime Minister has appointed Mr. Robert that the, said Sergeant Alexander McCabe shall from Arthur Atkinson, at present a Principal Officer in this day cease to excercise the powers and perform the Ministry of Agriculture, to be an Assistant Sec- the duties of an Inspector under the said Act. retary in the Cabinet Offices with effect from 15th February, 1962. BRIAN FAULKNER, Minister of Home Affairs for Northern Ireland. Stormont, Belfast, 4. MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS FOR 15th January, 1962. NORTHERN IRELAND EXPLOSIVES ACT, 1875 In virtue of the power conferred on me by Section 53 of the Explosives Act, 1875, and of every other ULSTER FOLK MUSEUM power enabling me in this behalf, I, The Right Honourable Brian Faulkner, M.P., being the Minis- BOARD OF TRUSTEES ter of Home Affairs for Northern Ireland, hereby appoint Sergeant Norman Wallace Scullion (No. In accordance with the provisions of the Ulster 7309) of the Royal Ulster Constabulary as an In- Folk Museum Act (Northern Ireland), 1958, the spector for Northern Ireland under the said Act and following persons have been appointed to serve as do hereby direct him to exercise only such powers Trustees for a period of three years from 1st and to perform such duties under the said Act as I October, 1961, except where otherwise stated :— shall from time to time assign to him. Appointed by the Senate of the Queen's University BRIAN FAULKNER, of Belfast Minister of Home Affairs for Professor E. -

The Troubles in Northern Ireland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Spring 2002 Thesis for the Cand.Polit degree in Political Science The Troubles in Northern Ireland. A Civil War in the United Kingdom – against all odds? Ingegerd Skogen Sulutvedt Department of Political Science University of Oslo Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 4 MAP OF UNITED KINGDOM 6 MAP OF NORTHERN IRELAND 6 1. INTRODUCTION 7 1.1. THE PROBLEM 9 1.2. METHOD 10 1.2.1. WHY NORTHERN IRELAND IS A SPECIAL CASE STUDY 10 1.2.2. NORTHERN IRELAND: A CASE STUDY 12 1.2.3. CASE STUDIES: LIMITATIONS 13 1.2.4. DATA AND RELIABILITY 14 2. CAUSES OF ARMED CONFLICTS 16 2.1. ARMED CONFLICTS, REGIME TYPES, AND DIFFERENT PARTS OF THE WORLD DEFINED 17 2.2. THEORIES ABOUT ARMED CONFLICTS 20 2.2.1. REGIME TYPE AND ARMED CONFLICTS 20 2.2.1.1. Consociational Democracy 24 2.2.2. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND ARMED CONFLICTS 29 2.3. THE HYPOTHESIS OF AN INVERTED U-CURVE 32 2.4. WHAT TYPES OF ARMED CONFLICTS ARISE? 35 2.5. THE THEORY OF RELATIVE DEPRIVATION 37 2.5.1. RELATIVE DEPRIVATION DEFINED 37 2.5.2. VIOLENCE: WHO AND WHY? 39 3. IRISH HISTORY 40 3.1. ISLANDS AT WAR 40 3.2. FROM THE NORMAN INVASION TO THE BATTLE OF BOYNE 41 3.3. IRELAND: A PART OF GREAT BRITAIN 45 3.4. THE BIRTH OF NORTHERN IRELAND 51 3.5. NORTHERN IRELAND 1921-1960S 54 3.5.1. -

Civil Rights and Civil Responsibilities

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives CIVIL RIGHTS AND CIVIL RESPONSIBILITIES HOW THE UNIONIST PARTY PERCEIVED AND RESPONDED TO THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT IN NORTHERN IRELAND 19681968----19721972 Master thesis in historhistoryy submitted at the UniversityUniversity of Bergen May 2010 His 350 Eirik Søreide Klepaker DDDepartmentDepartment of archaeoloarchaeology,gy, history, cultural studies and religion Front picture found at: http://www.nicivilrights.org/wp- content/uploads/2008/12/burntollet20march.jpg ii Thanks to Sissel Rosland, for giving me assistance and motivation when it was exceedingly needed. My Mum and Dad My fellow students iii iv Contents List of abbreviations...............................................................................................................vii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 Subject outline and previous research................................................................................ 1 Main questions ................................................................................................................... 4 Political and religious labels .............................................................................................. 4 Sources ............................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter outline ..................................................................................................................