The Paramountcy of Multidimensional Moral Hierarchy in the System of a Down Discography Jesse A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside This Week

Thu'rsday A Student Publication November I, too? Volume 52 Issue 8 UNIVERSITY 0 F WISCONSIN-STEVENS PO INT Locked and loaded: UW-SP PrQ.tective Services to introduce armed police officers t·o campus Sara Suchy police on campus 24 hours a an increasing number of peo "Our number one concern consult SCA before making THE POINTER day, seven days a week. ple who are hostile towards has always been the safety the decision to arm police offi [email protected] .EDU "Currently we are the only them. Most of these people of our students; we take that cers. campus in the UW-System to are not students, but it is not very, very seriously." "Some students are con not already have armed police fair to our officers to put them Student Government cerned that having guns on Students at the University officers," said Bob Tomlinson, campus will provoke violence. of Wisconsin-Stevens Point Vice Chancellor of Student Some students actually feel might be seeing more armed Affairs. unsafe having guns around police officers patrolling cam Chancellor Linda Bunnell campus," said Goldowski. pus in the near future after a is also expected to mandate Tomlinson views the ini committee organized by the that the UW-SP campus have tiative as a means of prevent Board of Regents to evalu armed police officers before ing a tragedy like Virginia Tech ate security of uw campus the entire UW-System requires from happening at UW-SP. es presents their report next it. "If something like Virginia week. Currently, there are three Tech happened here, the first "Immediately following full-fledged police officers on thing people would say is we the Virginia Tech shooting last campus and that number is need to have armed police on spring, President Kevin Reilly expected to climb to seven in campus to keep the students [president of the University the near future. -

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Download System of a Down Steal This Album Rar

Download system of a down steal this album rar CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Listen free to System of a Down – Steal This Album! (Chic 'N' Stu, Innervision and more). 16 tracks (). is the third album by System of a Down. Produced by Rick Rubin and Daron Malakian, Steal This Album! was recorded in mid and released on November 26, by American Recordings. The album reached No. 15 in the Billboard Top System Of A Down-System Of A renuzap.podarokideal.ru 0; Size 38 MB; Fast download for credit 37 sekund - 0,01 € Slow download for free System Of A Down-Steal This renuzap.podarokideal.ru 41 MB; 0. Korpiklanni-Voice Of Wilderness rar. 59 MB; 0. Harlej - Čtyři z punku a renuzap.podarokideal.ru 58 MB; 0. Fast download for credit 38 sekund - 0,01 System of a Down - Steal this renuzap.podarokideal.ru 52 MB +1. System Of A Down - renuzap.podarokideal.ru 41 MB; 0. Iron Maiden - Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son ().rar. 42 MB +1. Wanastowi Vjecy - Lži,sex a renuzap.podarokideal.ru Steal This Album! System Of A Down. 16 tracks. Released in Tracklist. Listen free to System of a Down – Steal This Album. Incorrect tagging this album is called Steal This Album! Please correct your tags Discover more music, concerts, videos, and pictures with the largest catalogue online at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Studio Album (7) - Single (1) About six months after Mezmerize, System Of A Down released its direct follow-up, Hypnotize. Steal This Album! is the third studio album by System of a Down, released on November 26, , on American renuzap.podarokideal.rued by Rick Rubin and Daron Malakian, and reached #15 in the Billboard Top Both Serj Tankian and John Dolmayan have called Steal This Album! their favorite System of a Down Genre: Alternative metal. -

THE ARMENIAN Mirrorc SPECTATOR Since 1932

THE ARMENIAN MIRRORc SPECTATOR Since 1932 Volume LXXXXI, NO. 42, Issue 4684 MAY 8, 2021 $2.00 Rep. Kazarian Is Artsakh Toun Proposes Housing Solution Passionate about For 2020 Artsakh War Refugees Public Service By Harry Kezelian By Aram Arkun Mirror-Spectator Staff Mirror-Spectator Staff EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I. — BRUSSELS — One of the major results Katherine Kazarian was elected of the Artsakh War of 2020, along with the Majority Whip of the Rhode Island loss of territory in Artsakh, is the dislocation State House in January, but she’s no of tens of thousands of Armenians who have stranger to politics. The 30-year-old lost their homes. Their ability to remain in Rhode Island native was first elected Artsakh is in question and the time remain- to the legislative body 8 years ago ing to solve this problem is limited. Artsakh straight out of college at age 22. Toun is a project which offers a solution. Kazarian is a fighter for her home- The approach was developed by four peo- town of East Providence and her Ar- ple, architects and menian community in Rhode Island urban planners and around the world. And despite Movses Der Kev- the partisan rancor of the last several orkian and Sevag years, she still loves politics. Asryan, project “It’s awesome, it’s a lot of work, manager and co- but I do love the job. And we have ordinator Grego- a great new leadership team at the ry Guerguerian, in urban planning, architecture, renovation Khanumyan estimated that there are State House.” and businessman and construction site management in Arme- around 40,000 displaced people willing to Kazarian was unanimously elect- and philanthropist nia, Belgium and Lebanon. -

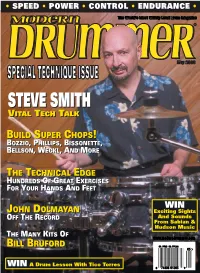

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

Balakian Finds His Place in Dual Cultural Identity

NOVEMBER 21, 2015 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVI, NO. 19, Issue 4413 $ 2.00 NEWS INBRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Philanthropist Pledges ADL, Tekeyan $1 million for Telethon YEREVAN — The Hayastan All-Armenian Fund Members announces that Russian-Armenian industrialist and benefactor Samvel Karapetyan has pledged to con- tribute $1 million to the fund’s upcoming Convene in Thanksgiving Day Telethon. The telethon’s primary goal this year is to raise funds for the construction of single-family homes Armenia for families in Nagorno Karabagh who have five or YEREVAN — On November 2, members more children and lack adequate housing. Thanks and leaders of the Armenian Democratic to Karapetyan’s donation, some 115 children and Liberal Party (ADL) from several countries their parents will be provided with comfortable, assembled at the entrance of Building No. fully furnished homes. 47 of Yerevan’s Republic Street (formerly “We are grateful to our friend Samvel known as Alaverdian Street) to attend the Karapetyan, who for years has generously support- dedication of the ADL premises. ed our projects,” said Ara Vardanyan, executive The building, which houses the offices of director of the Hayastan All-Armenian Fund, and the ADL-Armenia, the editorial offices of added, “I’m confident that many of our compatriots Azg newspaper, the library, and the meeting will follow in his footsteps.” halls, has been fully renovated and refur- The telethon will air for 12 hours on bished by ADL friend and well-known phil- Thanksgiving Day, November 26, beginning at 10 anthropist from New Jersey, Nazar a.m. -

System Sugar

FENDER PLAYERS CLUB SYSTEM OF A DOWN From the book: Best of Aggro-Metal Signature Licks by Troy Stetina #HL 695592. Book/CD $19.95 (US). AUDIO CLIP AUDIO CLIP - Slow Read more... SUGAR - Chorus (Guitar) Words and music by Daron Malakian, Serj Tankian, Shavo Odadjian, and John Dolmayan Copyright©1998 Sony/ATV Tunes LLC and Ddevil Music All Rights Administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 327203 International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved System of a Down is the collaboration of four musicians from L.A. that share one relatively unusual characteristic—they are all of Armenian heritage. Serj Tankian (vocals) and Daron Malakian (guitar) met in 1993 as their two bands shared the same rehearsal studio. Shortly thereafter, they united under the name Soil. After several lineup changes, including the addition of Shavo Odadjian (bass) and John Dolmayan (drums), System of a Down was finally born in 1995. Amid lyrical assaults ranging from the personal to aggressive political and social indictments, SOAD draws upon an unusually wide range of stylistic influences including rap, jazz, hardcore, goth, Middle-Eastern, and even Armenian music. Dynamics can change on a dime. Vocalist/lyricist Serj explains, “We don’t just concentrate on an aggressive sound, though we have that. Anger becomes more angry when you’re quiet at first.” Nowhere is that better exemplified than in “Sugar,” the third cut from their self- titled 1998 debut. First, a word about the tone: More than any other band in this book, the guitars in “Sugar” have a pronounced lower midrange peak in the 600-800 Hz range. -

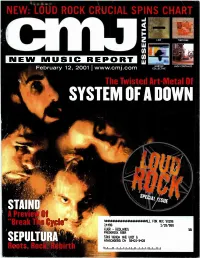

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

Nu-Metal As Reflexive Art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Porcello, Niccolo, "Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 580. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AFFECTIVE!MASCULINITES!AND!SUBURBAN!IDENTITIES:!! NU2METAL!AS!REFLEXIVE!ART! ! ! ! ! ! Niccolo&Dante&Porcello& April&25,&2016& & & & & & & Senior&Thesis& & Submitted&in&partial&fulfillment&of&the&requirements& for&the&Bachelor&of&Arts&in&Urban&Studies&& & & & & & & & _________________________________________ &&&&&&&&&Adviser,&Leonard&Nevarez& & & & & & & _________________________________________& Adviser,&Justin&Patch& Porcello 1 This thesis is dedicated to my brother, who gave me everything, and also his CD case when he left for college. Porcello 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Click Click Boom ............................................................................................. -

Acoustic Guitar

45 ACOUSTIC GUITAR THE CHRISTMAS ACOUSTIC GUITAR METHOD FROM ACOUSTIC GUITAR MAGAZINE COMPLETE SONGS FOR ACOUSTIC BEGINNING THE GUITAR GUITAR ACOUSTIC METHOD GUITAR LEARN TO PLAY 15 COMPLETE HOLIDAY CLASSICS METHOD, TO PLAY USING THE TECHNIQUES & SONGS OF by Peter Penhallow BOOK 1 AMERICAN ROOTS MUSIC Acoustic Guitar Private by David Hamburger by David Hamburger Lessons String Letter Publishing String Letter Publishing Please see the Hal Leonard We’re proud to present the Books 1, 2 and 3 in one convenient collection. Christmas Catalog for a complete description. first in a series of beginning ______00695667 Book/3-CD Pack..............$24.95 ______00699495 Book/CD Pack...................$9.95 method books that uses traditional American music to teach authentic THE ACOUSTIC EARLY JAZZ techniques and songs. From the folk, blues and old- GUITAR METHOD & SWING time music of yesterday have come the rock, country CHORD BOOK SONGS FOR and jazz of today. Now you can begin understanding, GUITAR playing and enjoying these essential traditions and LEARN TO PLAY CHORDS styles on the instrument that truly represents COMMON IN AMERICAN String Letter Publishing American music: the acoustic guitar. When you’re ROOTS MUSIC STYLES Add to your repertoire with done with this method series, you’ll know dozens of by David Hamburger this collection of early jazz the tunes that form the backbone of American music Acoustic Guitar Magazine and swing standards! The and be able to play them using a variety of flatpicking Private Lessons companion CD features a -

System of a Down Toxicity Download Zip

System Of A Down Toxicity Download Zip System Of A Down Toxicity Download Zip 1 / 3 2 / 3 Explore the largest community of artists, bands, podcasters and creators of music & audio.. System Of A Down Lyrics - Download Albums from Zortam Music. ... System Of A Down - Toxicity (UK CDS1) - Zortam Music · System Of A Down · Toxicity (UK .... A playlist featuring System Of A Down. ... SOAD Download. By Rebeca Caro. 29 songs. Play on Spotify. 1. Soldier Side - IntroSystem Of A Down • Mezmerize.. Myarcop : Download Lagu Full Album Mp3 System Of A Down ... Track Full Album System Of A Down (1995)-(2011) : .... System Of A Down - [2001] - Toxicity.. System Of A Down- Toxicity (Album Download). Tracklist: 1. Prison Song 2. Needles 3. Deer Dance 4. Jet Pilot 5. X 6. Chop Suey! 7. Bounce 8.. To listen System Of A Down music just click Play To download System Of A Down ... Music downloads System of a Down – Toxicity full album in zip or rar files.. Shimmy, 12. Toxicity, 13. Psycho, 14. Aerials. ... Toxicity. System Of A Down. 14 tracks. Released in 2001. Rock. Download album. Tracklist. 01. Prison Song. 02.. Donor challenge: For only a few more days, your donation will be matched 2-to-1. Triple your impact! To the Internet Archive Community,.. If you still have trouble downloading system of down toxicity album or any other file, post it in comments below and our support zip or a .... Mezmerize · Steal This Album - System Of A Down · Steal This Album · TOXICITY - System Of A Down · Toxicity · System Of A Down - Bonus Pack ... -

CHOP SUEY! As Recorded by System of a Down (From the 2001 Album "Toxicity")

CHOP SUEY! As recorded by System of a Down (from the 2001 Album "Toxicity") Transcribed by Idioteque0170 Words by Serj Tankian and Daron Malakian Music by Daron Malakian Arranged by Idioteque0170 A5A5 F5F5 C5C5 F/FA/A xxxx 7fr. xxxx x xxx xo x A Intro Moderately P = 128 Am Bm/A Rhy. Fig. 1 1 e 4 V V V V V V V V V V V Ie 4 V V V V V V V V V V V V V V f V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V Gtr I mf let ring T 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 4 A 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 5 B 0 0 0 0 0 0 sl. G/A F/A End Rhy. Fig. 1 3 e Ie f V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V let ring T 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 A 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 B 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 sl.