Selling Location: Illinois Town Advertisements, 1835-1837

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amphibian and Reptile Surveys in the Kaskaskia River Drainage of Illinois During 1997 and 1998

Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS Volume 107 Number 3-4 Article 27 2000 Amphibian and Reptile Surveys in the Kaskaskia River Drainage of Illinois During 1997 and 1998 Allan K. Wilson Southern Illinois University at Carbondale Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright © Copyright 2000 by the Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias Part of the Anthropology Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Allan K. (2000) "Amphibian and Reptile Surveys in the Kaskaskia River Drainage of Illinois During 1997 and 1998," Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS, 107(3-4), 203-205. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias/vol107/iss3/27 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jour. Iowa Acad. Sci. 107(3):203-205, 2000 Amphibian and Reptile Surveys in the Kaskaskia River Drainage of Illinois During 1997 and 1998 ALLAN K. WILSON Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Carbondale, Illinois 62901-6501 Email: [email protected] Currently there is little doubt among the scientific community of Interstate 64 and lay within the largest unfragmented forest tract in the decline of amphibians on an international scale (Berger et al. Illinois. -

2012 Newsletter.Pub

September 21, 2012 marked the 75th anniversary of the laying of the Physical Science Build- ing cornerstone. University Archives. Physical Science Building cornerstone ceremony with Annie Weller, 1937. University Archives 3 Message from the Chair Dear Alumni, I’d like to take this opportunity to pass along my greetings and to give you a taste of what’s been happening in the Geology/Geography Department over the past year. From a personnel standpoint, there are no major changes to report: we have no retirements or new tenure-track hires to announce. We do, however, have a new face in the department for this academic year. I’m pleased to introduce Dr. Elisabet Head (Ph.D. in Geology-Michigan Tech University, 2012), who will serve as a one- year sabbatical replacement for Dr. Craig Chesner. Craig will use the sabbatical to concentrate on research related to the Lake Toba region in Sumatra, Indonesia. Welcome, Elisabet! Among other changes at EIU, we have a new Dean of the College of Sciences, Dr. Harold Ornes. Dean Ornes comes to us from Winona State University Mike Cornebise, Ph.D., Associate Profes- in Minnesota. Welcome Dean Ornes! The sor of Geography, and Chair G/G faculty continue to remain active on many different fronts. You can read about their individual achievements in this newsletter. Beginning in spring semester of last year, we kicked off a new multi-disciplinary Professional Science Master’s program in Geographic Information Sciences. As the name suggests, the goal of the program is to allow students to enhance skills in the geographic techniques areas and to foster professional development. -

Interview with Dawn Clark Netsch # ISL-A-L-2010-013.07 Interview # 7: September 17, 2010 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Dawn Clark Netsch # ISL-A-L-2010-013.07 Interview # 7: September 17, 2010 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Friday, September 17, 2010 in the afternoon. I’m sitting in an office located in the library at Northwestern University Law School with Senator Dawn Clark Netsch. Good afternoon, Senator. Netsch: Good afternoon. (laughs) DePue: You’ve had a busy day already, haven’t you? Netsch: Wow, yes. (laughs) And there’s more to come. DePue: Why don’t you tell us quickly what you just came from? Netsch: It was not a debate, but it was a forum for the two lieutenant governor candidates sponsored by the group that represents or brings together the association for the people who are in the public relations business. -

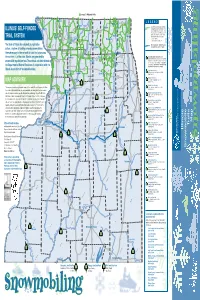

Illinois Snowmobile Trails

Connects To Wisconsin Trails East g g Dubuque g Warren L E G E N D 26 Richmond 173 78 Durand E State Grant Assisted Snowmobile Trails N Harvard O Galena O on private lands, open to the public. For B ILLINOIS’ SELF-FUNDED 75 E K detailed information on these trails, contact: A 173 L n 20 Capron n Illinois Association of Snowmobile Clubs, Inc. n P.O. Box 265 • Marseilles, IL 61341-0265 N O O P G e A McHenry Gurnee S c er B (815) 795-2021 • Fax (815) 795-6507 TRAIL SYSTEM Stockton N at iv E E onica R N H N Y e-mail: [email protected] P I R i i E W Woodstock N i T E S H website: www.ilsnowmobile.com C Freeport 20 M S S The State of Illinois has adopted, by legislative E Rockford Illinois Department of Natural Resources I 84 l V l A l D r Snowmobile Trails open to the public. e Belvidere JO v action, a system of funding whereby snowmobilers i R 90 k i i c Algonquin i themselves pay for the network of trails that criss-cross Ro 72 the northern 1/3 of the state. Monies are generated by Savanna Forreston Genoa 72 Illinois Department of Natural Resources 72 Snowmobile Trail Sites. See other side for detailed L L information on these trails. An advance call to the site 64 O Monroe snowmobile registration fees. These funds are administered by R 26 R E A L is recommended for trail conditions and suitability for C G O Center Elgin b b the Department of Natural Resources in cooperation with the snowmobile use. -

The History of Economic Inequality in Illinois

The History of Economic Inequality in Illinois 1850 – 2014 March 4, 2016 Frank Manzo IV, M.P.P. Policy Director Illinois Economic Policy Institute www.illinoisepi.org The History of Economic Inequality in Illinois EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Illinois Economic Policy Institute study is the first ever historical analysis of economic inequality in Illinois. Illinois blossomed from a small agricultural economy into the transportation, manufacturing, and financial hub of the Midwest. Illinois has had a history of sustained population growth. Since 2000, the state’s population has grown by over 460,000 individuals. As of 2014, 63 percent of Illinois’ population resides in a metropolitan area and 24 percent have a bachelor’s degree or more – both historical highs. The share of Illinois’ population that is working has increased over time. Today, 66 percent of Illinois’ residents are in the labor force, up from 57 percent just five decades ago. Employment in Illinois has shifted, however, to a service economy. While one-third of the state’s workforce was in manufacturing in 1950, the industry only employs one-in-ten Illinois workers today. As manufacturing has declined, so too has the state’s labor movement: Illinois’ union coverage rate has fallen by 0.3 percentage points per year since 1983. The decade with the lowest property wealth inequality and lowest income inequality in Illinois was generally the 1960s. In these years, the Top 1 Percent of homes were 2.2 times as valuable as the median home and the Top 1 Percent of workers earned at least 3.4 times as much as the median worker. -

Community Context: Influence and Implications for School Leadership Preparation

School Leadership Review Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 3 2019 Community Context: Influence and Implications for School Leadership Preparation Tamara Lipke State University of New York at Oswego, [email protected] Holly Manaseri University of Rochester, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Educational Leadership Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Lipke, Tamara and Manaseri, Holly (2019) "Community Context: Influence and Implications for School Leadership Preparation," School Leadership Review: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol14/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in School Leadership Review by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lipke and Manaseri: Community Context Community Context: Influence and Implications for School Leadership Preparation Tamara Lipke State University of New York at Oswego Holly Manaseri University of Rochester Introduction Research on school leadership shows that principals can significantly impact student achievement by influencing classroom instruction, organizational conditions, community support and setting the teaching and learning conditions in schools (Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2004). Moreover, strong principals provide a multiplier effect that enables improvement initiatives to succeed (Manna, 2015). Yet each year, as many as 22% of current principals retire or leave their schools or the profession (U.S. Department of Education, 2014) requiring districts to either promote or hire new principals to fill vacancies (School Leaders Network, 2014). -

THE ECONOMY of CANADA in the NINETEENTH CENTURY Marvin Mcinnis

2 THE ECONOMY OF CANADA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY marvin mcinnis FOUNDATIONS OF THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY CANADIAN ECONOMY For the economy of Canada it can be said that the nineteenth century came to an end in the mid-1890s. There is wide agreement among observers that a fundamental break occurred at about that time and that in the years thereafter Canadian economic development, industrialization, population growth, and territorial expansion quickened markedly. This has led economic historians to put a special emphasis on the particularly rapid economic expansion that occurred in the years after about 1896. That emphasis has been deceptive and has generated a perception that little of consequence was happening before 1896. W. W. Rostow was only reflecting a reasonable reading of what had been written about Canadian economic history when he declared the “take-off” in Canada to have occurred in the years between 1896 and 1913. That was undoubtedly a period of rapid growth and great transformation in the Canadian economy and is best considered as part of the twentieth-century experience. The break is usually thought to have occurred in the mid-1890s, but the most indicative data concerning the end of this period are drawn from the 1891 decennial census. By the time of the next census in 1901, major changes had begun to occur. It fits the available evidence best, then, to think of an early 1890s end to the nineteenth century. Some guidance to our reconsideration of Canadian economic devel- opment prior to the big discontinuity of the 1890s may be given by a brief review of what had been accomplished by the early years of that decade. -

2013 Candidates for the Presidential

Candidates for the Presidential Scholars Program January 2013 [*] An asterisk indicates a Candidate for Presidential Scholar in the Arts. Candidates are grouped by their legal place of residence; the state abbreviation listed, if different, may indicate where the candidate attends school. Alabama AL ‐ Alabaster ‐ Casey R. Crownhart, Jefferson County International Baccalaureate School AL ‐ Alabaster ‐ Ellis A. Powell, The Altamont School AL ‐ Auburn ‐ Harrison R. Burch, Auburn High School AL ‐ Auburn ‐ Nancy Z. Fang, Auburn High School AL ‐ Auburn ‐ Irene J. Lee, Auburn High School AL ‐ Auburn ‐ Kaiyi Shen, Auburn High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Deanna M. Abrams, Alabama School of Fine Arts AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Emily K. Causey, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Robert C. Crumbaugh, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Emma C. Jones, Jefferson County International Baccalaureate School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Frances A. Jones, Jefferson County International Baccalaureate School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Benjamin R. Kraft, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Amy X. Li, Vestavia Hills High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Botong Ma, Vestavia Hills High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Alexander C. Mccullumsmith, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Alexander S. Oser, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Ann A. Sisson, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Thomas M. Sisson, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Supraja R. Sridhar, Jefferson County International Baccalaureate School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Paul J. Styslinger, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Meredith E. Thomley, Vestavia Hills High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Sarah Grace M. Tucker, Mountain Brook High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Jacob D. Van Geffen, Oak Mountain High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Kevin D. Yang, Spain Park High School AL ‐ Birmingham ‐ Irene P. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Former Governors of Illinois

FORMER GOVERNORS OF ILLINOIS Shadrach Bond (D-R*) — 1818-1822 Illinois’ first Governor was born in Maryland and moved to the North - west Territory in 1794 in present-day Monroe County. Bond helped organize the Illinois Territory in 1809, represented Illinois in Congress and was elected Governor without opposition in 1818. He was an advo- cate for a canal connecting Lake Michigan and the Illinois River, as well as for state education. A year after Bond became Gov ernor, the state capital moved from Kaskaskia to Vandalia. The first Illinois Constitution prohibited a Governor from serving two terms, so Bond did not seek reelection. Bond County was named in his honor. He is buried in Chester. (1773- 1832) Edward Coles (D-R*) — 1822-1826 The second Illinois Governor was born in Virginia and attended William and Mary College. Coles inherited a large plantation with slaves but did not support slavery so he moved to a free state. He served as private secretary under President Madison for six years, during which he worked with Thomas Jefferson to promote the eman- cipation of slaves. He settled in Edwardsville in 1818, where he helped free the slaves in the area. As Governor, Coles advocated the Illinois- Michigan Canal, prohibition of slavery and reorganization of the state’s judiciary. Coles County was named in his honor. He is buried in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1786-1868) Ninian Edwards (D-R*) — 1826-1830 Before becoming Governor, Edwards was appointed the first Governor of the Illinois Territory by President Madison, serving from 1809 to 1818. Born in Maryland, he attended college in Pennsylvania, where he studied law, and then served in a variety of judgeships in Kentucky. -

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois 1492 - The first Europeans come to North America. 1600 - The land that is to become Illinois encompasses 21 million acres of prairie and 14 million acres of forest. 1680 - Fort Crevecoeur is constructed by René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and his men on the bluffs above the Illinois River near Peoria. A few months later, the fort is destroyed. You can read more about the fort at http://www.ftcrevecoeur.org/history.html. 1682 - René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and Henri de Tonti reach the mouth of the Mississippi River. Later, they build Fort St. Louis atop Starved Rock along the Illinois River. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://more.pjstar.com/peoria-history/ 1699 - A Catholic mission is established at Cahokia. 1703 - Kaskaskia is established by the French in southwestern Illinois. The site was originally host to many Native American villages. Kaskaskia became an important regional center. The Illinois Country, including Kaskaskia, came under British control in 1765, after the French and Indian War. Kaskaskia was taken from the British by the Virginia militia in the Revolutionary War. In 1818, Kaskaskia was named the first capital of the new state of Illinois. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/kaskaskia.html 1717 - The original French settlements in Illinois are placed under the government of Louisiana. 1723 - Prairie du Rocher is settled. http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/prairie-du-rocher.html 1723 - Fort de Chartres is constructed. -

The Driftless Area – a Physiographic Setting (Dale K

A Look Back at Driftless Area Science to Plan for Resiliency in an Uncertain Future th Special Publication of the 11 Annual Driftless Area Symposium 1 A Look Back at Driftless Area Science to Plan for Resiliency in an Uncertain Future Special Publication of the 11th Annual Driftless Area Symposium Radisson Hotel, La Crosse, Wisconsin February 5th-6th, 2019 Table of Contents: Preface: A Look Back at Driftless Area Science to Plan for Resiliency in an Uncertain Future (Daniel C. Dauwalter, Jeff Hastings, Marty Melchior, and J. “Duke” Welter) ........................................... 1 The Driftless Area – A Physiographic Setting (Dale K. Splinter) .......................................................... 5 Driftless Area Land Cover and Land Use (Bruce Vondracek)................................................................ 8 Hydrology of the Driftless Area (Kenneth W. Potter) ........................................................................... 15 Geology and Geomorphology of the Driftless Area (Marty Melchior) .............................................. 20 Stream Habitat Needs for Brown Trout and Brook Trout in the Driftless Area (Douglas J. Dieterman and Matthew G. Mitro) ............................................................................................................ 29 Non-Game Species and Their Habitat Needs in the Driftless Area (Jeff Hastings and Bob Hay) .... 45 Climate Change, Recent Floods, and an Uncertain Future (Daniel C. Dauwalter and Matthew G. Mitro) .........................................................................................................................................................