Andrew Jackson and the War of 1812

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of the Indiana Lenape

IN SEARCH OF THE INDIANA LENAPE: A PREDICTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE LENAPE LIVING ALONG THE WHITE RIVER IN INDIANA FROM 1790 - 1821 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY JESSICA L. YANN DR. RONALD HICKS, CHAIR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 Table of Contents Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Research Goals ............................................................................................................................ 1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 2: Theory and Methods ................................................................................................. 6 Explaining Contact and Its Material Remains ............................................................................. 6 Predicting the Intensity of Change and its Effects on Identity................................................... 14 Change and the Lenape .............................................................................................................. 16 Methods .................................................................................................................................... -

Junaluska, the Cherokee Who Saved Andrew Jackson's Life and Made Him a National Hero, Lived to Regret It

Junaluska, the Cherokee who saved Andrew Jackson’s life and made him a national hero, lived to regret it. Born in the North Carolina mountains around 1776, he made his name and his fame among his own people in the War of 1812 when the mighty tribe of Creek Indians allied themselves with the British against the United States. At the start of the Creek War, Junaluska recruited some 800 Cherokee warriors to go to the aid of Andrew Jackson in northern Alabama. Joined by reinforcements from Tennessee, including more Cherokee, the Cherokee spent the early months of 1814 performing duties in the rear, while Jackson and his Tennessee militia moved like a scythe through the Creek towns. However, that March word came that the Creek Indians were massed behind fortifications at Horseshoe Bend. Jackson, with an army of 2,000 men, including 500 Cherokee led by Junaluska, set out for the Bend, 70 miles away. There, the Tallapoosa River made a bend that enclosed 100 acres in a narrow peninsula opening to the north. On the lower side was an island in the river. Across the neck of the peninsula the Creek had built a strong breastwork of logs and hidden dozens of canoes for use if retreat became necessary. Storming The Fort: The fort was defended by 1,000 warriors. There also were 300 women and children. As cannon fire bombarded the fort, the Cherokee crossed the river three miles below and surrounded the bend to block the Creek escape route. They took position where the Creek fort was separated from them by water. -

River Raisin National Battlefield Park Lesson Plan Template

River Raisin National Battlefield Park 3rd to 5th Grade Lesson Plans Unit Title: “It’s Not My Fault”: Engaging Point of View and Historical Perspective through Social Media – The War of 1812 Battles of the River Raisin Overview: This collection of four lessons engage students in learning about the War of 1812. Students will use point of view and historical perspective to make connections to American history and geography in the Old Northwest Territory. Students will learn about the War of 1812 and study personal stories of the Battles of the River Raisin. Students will read and analyze informational texts and explore maps as they organize information. A culminating project will include students making a fake social networking page where personalities from the Battles will interact with one another as the students apply their learning in fun and engaging ways. Topic or Era: War of 1812 and Battles of River Raisin, United States History Standard Era 3, 1754-1820 Curriculum Fit: Social Studies and English Language Arts Grade Level: 3rd to 5th Grade (can be used for lower graded gifted and talented students) Time Required: Four to Eight Class Periods (3 to 6 hours) Lessons: 1. “It’s Not My Fault”: Point of View and Historical Perspective 2. “It’s Not My Fault”: Battle Perspectives 3. “It’s Not My Fault”: Character Analysis and Jigsaw 4. “It’s Not My Fault”: Historical Conversations Using Social Media Lesson One “It’s Not My Fault!”: Point of View and Historical Perspective Overview: This lesson provides students with background information on point of view and perspective. -

WEB Warof1812booklet.Pdf

1. Blount Mansion War of 1812 in Tennessee: 200 W. Hill Avenue, Knoxville A Driving Tour Governor Willie Blount, who served from 1809 to 1815, led Tennessee during the War of 1812. He lived in this sponsored and developed by the Center for Historic historic structure, originally the home of U.S. territorial Preservation, Middle Tennessee State University, Mur- freesboro Two hundred years ago, an international war raged across the United States of America. Thousands of American soldiers died in the conflict; the nation’s capital city was invaded, leaving both the White House and the U.S. Capitol in near ruins. An American invasion of Canada ended in failure. Defeat appeared to be certain—leaving the nation’s future in doubt—but down on the southern frontier Tennesseans fought and won major battles that turned the tide and made the reputation of a future U.S. president, Andrew Jackson. This conflict between the United States, Great Britain, governor William Blount (Willie’s older half-brother), Canada, and a score of sovereign Indian nations was called throughout the war. In 1813, Governor Blount raised the War of 1812 because the United States declared war over $37,000 and 2,000 volunteer soldiers to fight the on England in June of that year. Thousands of Tennesseans Creeks. Blount Mansion, built between 1792 and c.1830, fought with distinction in three southern campaigns: the is Knoxville’s only National Historic Landmark. 1813 Natchez campaign, the 1813–14 Creek War, and the campaign against the British in New Orleans in 1814–15. There were additional companies of Tennesseans and others 2. -

War of 1812 Primary Source Packet Madison

War of 1812 Primary Source Packet Madison Becomes President Digital History ID 211 Author: John Adams Date:1809 Annotation: Distressed by the embargo's failure, Jefferson looked forward to his retirement from the presidency. "Never," he wrote, "did a prisoner, released from his chains, feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power." The problem of American neutrality now fell to Jefferson's hand-picked successor, James Madison. A quiet and scholarly man, who secretly suffered from epilepsy, "the Father of the Constitution" brought a keen intellect and wealth of experience to the presidency. As Jefferson's Secretary of State, he had kept the United States out of the Napoleonic wars and was committed to using economic coercion to force Britain and France to respect America's neutral rights. In this letter, former President Adams notes Madison's ascension to the presidency. Document: Jefferson expired and Madison came to Life last night...I pity poor Madison. He comes to the helm in such a storm as I have seen in the Gul[f] Stream, or rather such as I had to encounter in the Government in 1797. Mine was the worst however, because he has a great Majority of the officers and Men attached to him Survival Strategies Digital History ID 662 Author: Tecumseh Date:1810 Annotation: Told by Governor Harrison to place his faith in the good intentions of the United States, Tecumseh offers a bitter retort. He calls on Native Americans to revitalize their societies so that they can regain life as a unified people and put an end to legalized land grabs. -

The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730--1795

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795 Richard S. Grimes West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grimes, Richard S., "The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4150. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4150 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730-1795 Richard S. Grimes Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth A. -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error. -

LENAPE VILLAGES of DELAWARE COUNTY By: Chris Flook

LENAPE VILLAGES OF DELAWARE COUNTY By: Chris Flook After the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, many bands of Lenape (Delaware) Native Americans found themselves without a place to live. During the previous 200 years, the Lenape had been pushed west from their ancestral homelands in what we now call the Hudson and Delaware river valleys first into the Pennsylvania Colony in the mid1700s and then into the Ohio Country around the time of the American Revolution. After the Revolution, many Natives living in what the new American government quickly carved out to be the Northwest Territory, were alarmed of the growing encroachment from white settlers. In response, numerous Native groups across the territory formed the pantribal Western Confederacy in an attempt to block white settlement and to retain Native territory. The Western Confederacy consisted of warriors from approximately forty different tribes, although in many cases, an entire tribe wasn’t involved, demonstrating the complexity and decentralized nature of Native American political alliances at this time. Several war chiefs led the Western Confederacy’s military efforts including the Miami chief Mihšihkinaahkwa (Little Turtle), the Shawnee chief Weyapiersenwah (Blue Jacket), the Ottawa chief Egushawa, and the Lenape chief Buckongahelas. The Western Confederacy delivered a series of stunning victories over American forces in 1790 and 1791 including the defeat of Colonel Hardin’s forces at the Battle of Heller’s Corner on October 19, 1790; Hartshorn’s Defeat on the following day; and the Battle of Pumpkin Fields on October 21. On November 4 1791, the forces of the territorial governor General Arthur St. -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

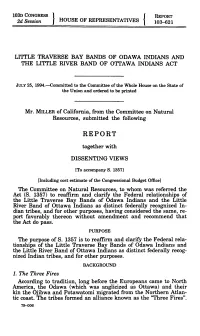

REPORT 2D Session HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES 103-621

103D CONGRESS } { REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 103-621 LITTLE TRAVERSE BAY BANDS OF ODAWA INDIANS AND THE LITTLE RIVER BAND OF OTrAWA INDIANS ACT JULY 25, 1994.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. MILLER of California, from the Committee on Natural Resources, submitted the following REPORT together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany S. 13571 [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Natural Resources, to whom was referred the Act (S.1357) to reaffirm and clarify the Federal relationships of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians as distinct federally recognized In- dian tribes, and for other purposes, having considered the same, re- port favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the Act do pass. PURPOSE The purpose of S. 1357 is to reaffirm and clarify the Federal rela- tionships of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians as distinct federally recog- nized Indian tribes, and for other purposes. BACKGROUND 1. The Three Fires According to tradition, long before the Europeans came to North America, the Odawa (which was anglicized as Ottawa) and their kin the Ojibwa and Potawatomi migrated from the Northern Atlan- tic coast. The tribes formed an alliance known as the "Three Fires". 79-006 The Ottawa/Odawa settled on the eastern shore of Lake Huron at what are now called the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island. In 1615, the Ottawa/Odawa formed a fur trading alliance with the French. -

Tennessee State Library and Archives WINCHESTER, JAMES

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 WINCHESTER, JAMES (1752-1856) PAPERS, 1787-1953 Processed by: Manuscript Division Archival Technical Services Accession Number: THS 27 Date Completed: October 11, 1967 Location: I-D-3 Microfilm Accession Number: 794 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION These papers for the years 1787-1953, relating primarily to the career and activities of General James Winchester, U.S. Army, were given to the Tennessee Historical Society by Mr. George Wynne, Castalian Springs, Tennessee. The materials in this collection measure 1.68 linear feet. There are no restrictions on the materials. Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the James Winchester Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research. SCOPE AND CONTENT The papers of General James Winchester, numbering approximately 1,100 items and two volumes, contain accounts (bills, notes, receipts), personal and military; correspondence; land records including claims, records, deeds, grants, papers dealing with Memphis land surveys and commissions, court minutes, summonses, etc. Correspondence, mainly James Winchester’s incoming (1793-1825) and outgoing (1796-1826), comprises about half the collection. In addition to the military correspondence, a great portion deals with land speculation. The largest number of letters from any one man to Winchester is that of Judge John Overton, who, apart from being Winchester’s confidant and friend, was his partner in land dealings. There are 116 pieces of correspondence with Overton, and these are primarily on the subject of Memphis lands as Winchester, Overton, and Andrew Jackson were extensively involved in the establishment and early growth of the community. -

THE WAR of 1812 in CLAY COUNTY, ALABAMA by Don C. East

THE WAR OF 1812 IN CLAY COUNTY, ALABAMA By Don C. East BACKGROUND The War of 1812 is often referred to as the “Forgotten War.” This conflict was overshadowed by the grand scale of the American Revolutionary War before it and the American Civil War afterwards. We Americans fought two wars with England: the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Put simply, the first of these was a war for our political freedom, while the second was a war for our economic freedom. However, it was a bit more complex than that. In 1812, the British were still smarting from the defeat of their forces and the loss of their colonies to the upstart Americans. Beyond that, the major causes of the war of 1812 were the illegal impressments of our ships’ crewmen on the high seas by the British Navy, Great Britain’s interference with our trade and other trade issues, and the British incitement of the Native Americans to hostilities against the Americans along the western and southeast American frontiers. Another, often overlooked cause of this war was it provided America a timely excuse to eliminate American Indian tribes on their frontiers so that further westward expansion could occur. This was especially true in the case of the Creek Nation in Alabama so that expansion of the American colonies/states could move westward into the Mississippi Territories in the wake of the elimination of the French influence there with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, and the Spanish influence, with the Pinckney Treaty of 1796. Now the British and the Creek Nation were the only ones standing in the way of America’s destiny of moving the country westward into the Mississippi Territories.