Sanitation, Sand & Shells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number of Soldiers That Joined the Army from Registered Address in Scotland for Financial Years 2014 to 2017

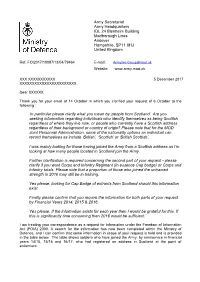

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: FOI2017/10087/13/04/79464 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk XXX XXXXXXXXXXX 5 December 2017 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Dear XXXXXX, Thank you for your email of 14 October in which you clarified your request of 6 October to the following : ‘In particular please clarify what you mean by ‘people from Scotland’. Are you seeking information regarding individuals who identify themselves as being Scottish regardless of where they live now, or people who currently have a Scottish address regardless of their background or country of origin? Please note that for the MOD Joint Personnel Administration, some of the nationality options an individual can record themselves as include ‘British’, ‘Scottish’ or ‘British Scottish’. I was mainly looking for those having joined the Army from a Scottish address as I’m looking at how many people located in Scotland join the Army. Further clarification is required concerning the second part of your request - please clarify if you want Corps and Infantry Regiment (In essence Cap badge) or Corps and Infantry totals. Please note that a proportion of those who joined the untrained strength in 2016 may still be in training. Yes please, looking for Cap Badge of entrants from Scotland should this information exist. Finally please confirm that you require the information for both parts of your request by Financial Years 2014, 2015 & 2016. Yes please, If the information exists for each year then I would be grateful for this. If this is significantly time consuming then 2016 would be sufficient.’ I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. -

Royal Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-22-02-21 on 1 February 1914. Downloaded from JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. <torps mews. FEBRUARY, 1914. HONOURS. The King has been graciously pleased to confer the honour of Knighthood upon Protected by copyright. Surgeon-General Arthur Thomas Sloggett, C.B., C.M.G., K.H.S., Director Medical Services in India. The King has been graciously pleased to give orders for the following appointment to the Most Honourable Order of the Bath: To be Ordinary Member of the Military Division, or Companion of the said Most Honourable Order: Surgeon;General Harold George Hathaway, Deputy Director of Medical Services, India. ESTABLISHMENTS. Royal Hospital, Chelsea: Lieutenant-Colonel George A. T. Bray, Royal Army Medical Corps, to be Deputy Surgeon, vice Lieutimant-Colonel H. E. Winter, who has vacated the appointment, dated January 20, 1914. ARMY MEDICAL SERYICE. Surgeon-General Owen E. P. Lloyd, V.C., C.B., is placed on retired pay, dated January 1, 1914. Colonel Waiter G. A. Bedford, C.M.G., to be Surgeon-General, vice O. E. P. Lloyd, V.C., C.B., dated January 1, 19]4. http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ Colonel Alexander F. Russell, C.M.G., M.B., is placed on retired pay, dated December 21, 1913. Colonel Thomas J. R. Lucas, C.B., M.B., on completion of four years' service in his rank, retires on retired pay. dated January 2, 1914. Colonel Robert Porter, M.B., on completion of four years' service in his rank, is placed on the half-pay list, dated January 14, 1914. -

Royal Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-16-01-16 on 1 January 1911. Downloaded from JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. (torps 1Rews. JANUARY, 1911. ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. The King has been pleased to give and grant unto Captain Howard Ensor, D.S.O., Royal Army Medical Corps, His Majesty's Royal licence and authority to accept and Protected by copyright. wear the Imperial Ottoman Order of the Osmanieh, Fourth Class, which has been conferred upon him by His Highness the Khedive of Egypt; authorised by His Imperial Majesty the Sultan of Turkey, in recognition of valuable services rendered by him. REGULAR FORCES. ESTABLISHMENTS. Royal Army Medical Corps School of Instruction.-Major Claude K. Morgan, M.B. R.A.M.C., to be an Instructor, vice Major C. C. Fleming, D.S.O., who has vacated that appointment. Dated October 29, 1910. CAVALRY. 1st Life Guards.-Surgeon·Captain Alfred C. Lupton, M.B., is placed temporarily on the half-pay list on accoun't of ill-health. Dated November, 22, 1910. ARMY MEDICAL SERVICE. Royal Army Medical Corps.-The undermentioned officers, from the seconded list, are restored to the Establishment, dated November 18, 1910 :-Captain William M. B. http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ Sparkes. Lieutenant Harold T. Treves. Captain Edward Gibbon, M.B., is seconded for service with the Egyptian Army. Dated November 13, 1910. ARRIVALS HOME FOR DUTY.-From India: On November 24, Lieutenant Colonel T. B. Winter; Captains C. H. Turner, J. P. Lynch, and E. G. R. Lithgow. From Straits Settlements: On November 29, Major I. -

Royal Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-07-01-23 on 1 July 1906. Downloaded from JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. (torp£; 'lRew£;. JULY, 1906. Protected by copyright. ARMY MEDICAL SERYICE.-GAZETTE NOTIFICATIONS. Lieutenant-Colonel James M. Irwin, lVLB., Royal Army Medical Corps, to be Assistant Director-General, vice Lieutenant-Colonel W. Babtie, V.O., O.M_G., M.B., Royal Army Medical Corps, whose tenure of that appointment has expired, dated June 1, 1906. ROYAL ARMY ME DICAL CORPS. The undermentioned Lieutenants to be Captains, dated March 1, 1906: Arthur B. Smallman, M.B., Went worth F. Tyndale, C.M.G., M.B.. Percival Davidson, D.S.O., M.B., William F. Ellis, John McKenzie, M.B., Norman D. Walker, M.B., Arthur H. Hayes, Henry J. Crossley, Ralph B. Ainsworth, Charles A. J. A. Balck, M.B., Reginald Storrs, Raymond L. V. Foster, 1ILB., Frederick A. H. Olarke, George A. K. H. Reed, John W. S. Seccombe, John 11£' H. Conway, Sydney M. W. Meadows, Herbert V. Bagshawe, DudleyS. Skelton, Oharles V. B. Stanley, M.D., Hugh G. S. Webb, William http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ W. Browne, Richard Rutherford, lILB., William D. ·C. Kelly, lILB., Norman E. J. Harding, M.B., Robert J. Franklin. Lieutenant Leonard Bousfield, lILB., is seconded for service with the Egyptian Army, dated April 30, 1906. Lieutenant Francis liT. IiI. Ommanney, from the seconded list, to be ·Lieutenant, dated May 14, 1906. Lieutenant Cuthbert G. Browne, from the seconded list, to be Lieutenant, dated June 1, 1906. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas H. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 13 December, 1945 6059

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13 DECEMBER, 1945 6059 Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Graham Alexander Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Alfred John ODLING- NORRIS (122649), Royal Electrical and Mechanical . SMEE (34483). The Royal Sussex Regiment (Kings- Engineers. boidge). Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) John O'DWYER Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Bernard Basil SMITH (31586), Corps of Royal Engineers (Newcastle-on- (47140), Corps of Royal Engineers. Tyne). Lieutenant Colonel Eric Bindloss SMITH (18074), Colonel (acting) Oswald James Ritchie OKR (31587), Royal Regiment of Artillery (Wantage). Corps of Royal Engineers (Sittingboume). Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) John Stuart Pope Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Sidney Walter OWEN SMITH (114966), Pioneer Coups (Leeds). (193970), Royal Army Ordnance Corps (Brighton Lieutenant Colonel (acting) Francis Joseph SODEN 6)- (133827), Royal Army Service Corps (E.F.I.).' Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Lionel Alfred Brading (Hinchley Wood, Surrey). PATEN (23680), Corps of Royal Engineers (Peter- Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Archibald Richard borough). Charles SOUTHBY (50234), The Rifle Brigade Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Gordon Oliver (Prince Consort's Own) (Andover). PEAKE (111907), Royal Army Service Corps (Wey- Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) James Eustace. bridge). SPEDDING (26887), Royal Regiment of Artillery Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Herbert Stanley (Keswick). PEARCE (59620), Pioneer Corps. The Reverend George Archibald Douglas SPENCE, Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Ralph Whitin PETERS M.C. (3422), Chaplain to the Forces, Second Class, (LA. 389), Indian Armoured Corps. New Zealand Military Forces. Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) John PETTIGREW Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Charles Richard (89927), Corps of Royal Engineers (Edinburgh). SPENCER (49923), i2th Royal Lancers (Prince of Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Robert Thomas Wales's), Koyal Armoured Corps (Yelverton). PRIEST, M.B.E. (39354), Royal Regiment of Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Henry Sydney Oh'ver Artillery. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 9Th May 1995 O.B.E

6612 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 9TH MAY 1995 O.B.E. in Despatches, Commended for Bravery or Commended for Valuable Service in recognition of gallant and distinguished services To be Ordinary Officers of the Military Division of the said Most in the former Republic of Yugoslavia during the period May to Excellent Order: November 1994: Lieutenant Colonel David Robin BURNS, M.B.E. (500341), Corps of Royal Engineers. Lieutenant Colonel (now Acting Colonel) James Averell DANIELL (487268), The Royal Green Jackets. ARMY Mention in Despatches M.B.E. To be Ordinary Members of the Military Division of the said Most Major Nicholas George BORWELL (504429), The Duke of Excellent Order: Wellington's Regiment. Major Duncan Scott BRUCE (509494), The Duke of Wellington's 2464S210 Corporal Stephen LISTER, The Royal Logistic Corps. Regiment. The Reverend Duncan James Morrison POLLOCK, Q.G.M., 24631429 Sergeant Sean CAINE, The Duke of Wellington's Chaplain to , the Forces 3rd Class (497489), Royal Army Regiment. Chaplains' Department. 24764103 Lance Corporal Carl CHAMBERS, The Duke of 24349345 Warrant Officer Class I (now Acting Captain) Ian Wellington's Regiment. SINCLAIR, Corps of Royal Engineers. 24748686 Lance Corporal (now Acting Corporal) Neil Robert 24682621 Corporal (now Sergeant) Nigel Edwin TULLY, Corps of FARRELL, Royal Army Medical Corps. Royal Engineers. Lieutenant Colonel (now Acting Colonel) John Chalmers McCoLL, Major Alasdair John Campbell WILD (514042), The Royal O.B.E., (495202), The Royal Anglian Regiment. Anglian Regiment. 24852063 Private (now Lance Corporal) Liam Patrick SEVIOUR, The Duke of Wellington's Regiment. ROYAL AIR FORCE O.B.E. Queen's Commendation for Bravery To be an Ordinary Officer of the Military Division of the said Most Excellent Order: 24652732 Corporal Mark David HUGHES, The Duke of Wing Commander (now Group Captain) Andrew David SWEETMAN Wellington's Regiment. -

TWICE a CITIZEN Celebrating a Century of Service by the Territorial Army in London

TWICE A CITIZEN Celebrating a century of service by the Territorial Army in London www.TA100.co.uk The Reserve Forces’ and Cadets’ Association for Greater London Twice a Citizen “Every Territorial is twice a citizen, once when he does his ordinary job and the second time when he dons his uniform and plays his part in defence.” This booklet has been produced as a souvenir of the celebrations for the Centenary of the Territorial Field Marshal William Joseph Slim, Army in London. It should be remembered that at the time of the formation of the Rifle Volunteers 1st Viscount Slim, KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC in 1859, there was no County of London, only the City. Surrey and Kent extended to the south bank of the Thames, Middlesex lay on the north bank and Essex bordered the City on the east. Consequently, units raised in what later became the County of London bore their old county names. Readers will learn that Londoners have much to be proud of in their long history of volunteer service to the nation in its hours of need. From the Boer War in South Africa and two World Wars to the various conflicts in more recent times in The Balkans, Iraq and Afghanistan, London Volunteers and Territorials have stood together and fought alongside their Regular comrades. Some have won Britain’s highest award for valour - the Victoria Cross - and countless others have won gallantry awards and many have made the ultimate sacrifice in serving their country. This booklet may be recognised as a tribute to all London Territorials who have served in the past, to those who are currently serving and to those who will no doubt serve in the years to come. -

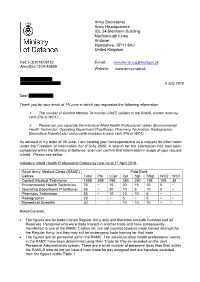

Numbers of Service Personnel in Royal Army Medical Corps at 1

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: FOI2018/08152 E-mail: [email protected] ArmySec/13/04/80609 Website: www.army.mod.uk XXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX 5 July 2018 Dear XXXXXXXXXX, Thank you for your email of 19 June in which you requested the following information: 1. The number of Combat Medical Technician (CMT) soldiers in the RAMC, broken down by rank (Pte to WO1). 2. Please can you separate the individual Allied Health Professional cadres (Environmental Health Technician, Operating Department Practitioner, Pharmacy Technician, Radiographer, Biomedical Scientist etc) and provide numbers in each rank (Pte to WO1). As advised in my letter of 25 June, I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm that information in scope of your request is held. Please see below: Individual Allied Health Professional Cadres by rank as at 1st April 2018. Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) Paid Rank Cadres Total Pte LCpl Cpl Sgt SSgt WO2 WO1 Combat Medical Technician 1895 395 495 380 290 195 105 35 Environmental Health Technician 75 ~ 15 20 15 10 5 ~ Operating Department Practitioner 55 ~ 20 10 5 10 5 ~ Pharmacy Technician 35 ~ 10 10 10 5 ~ - Radiographer 20 - ~ 5 ~ 5 ~ ~ Biomedical Scientist 30 - - 10 10 10 ~ - Notes/Caveats: • The figures are for trade trained Regular Army only and therefore exclude Gurkhas and all Reserves. Personnel who were trade trained in another trade and have subsequently transferred to one of the RAMC Cadres list, are still counted towards trade trained strength for the Regular Army, but they may still be undergoing trade training for that trade. -

Royal ,Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-10-06-22 on 1 June 1908. Downloaded from JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ,ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. (torps 1Aews. JUNE, 1908. ARMY MEDICAL SERYIOE.-GAZETTE NOTIFICATIONS. Surgeon-General William J. Charlton is placed on retired pay, dated April 11, 1908. He entered the Service April 1, 1871 ; was promoted Surgeon, Army Medical Depart ment, March 1, 1873; Surgeon-Major, April 1, 1883; Surgeon-Lieutenant-Colonel, Protected by copyright. April 1, 1891; Brigade-Surgeon-Lieutenant-Colonel, Army Medical Service, May 2, 1895; Colonel, Royal Army Medical Corps, July 1, 1899; Surgeon-General, Army Medical Staff, August 11, 1903. Colonel John C. Dorman, C.M.G., M.B., to be Surgeon-General, vice W. J.Charlton, dated April 11, 1908 Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Peterkin" M.B.; from the Royal Army Medical Corps, to be Colonel, vice J.' C. Dorman, C.M.G., M.B., dated April 11, 1908. Colonel Charles Seymour, M.B., is placed on retired pay, dated April 12, 1908. He entered the Service April 4, 1878; was promoted Surgeon-Major, August 4, 1890; Lieu tenant-Colonel, Royal Army Medical Corps, August 4, 1898; Lieutenant-Colonel, Royal Army Medical Corps, under Art. 365, Pay Warrant, December 26, 1901; seconded for service whilst holding the appointment of Physician and Surgeon at the Royal Hos pital, Chelsea" June 3,1904; Colonel, Army Medical Service, June 21, 1905. His war services are as follows: Soudan Expedition, 1885; Suakin, Medal with clasp, bronze star; Sudan, 1885-6; Frontier Field Force, Action of Giniss. http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. -

Royal Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-21-01-17 on 1 July 1913. Downloaded from JOURNAL OF.THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. / / <!orpa news. JULY, 1913. HONOURS. THE KING has been' graciously pleased, on the occasion of His Majesty's birthday, to give orders for the following appointments :-'--- To be Ordinary Member of the Military Division' of the Third Class, or Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, Surgeon-General Louis Edward Anderson, Deputy Director of Medical Services, Ireland. To be a Companion of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire: Major copyright. Robert James Blackham, R.A.M.C., commanding the Station Hospital, Jutogh. His Majesty has been further pleased to confer the honour of Knighthood upon Major Edward Scott Worthington, M.V.O., R.A.M.C. CAYALRY-1st LIFE GUARDS.-Surgeon-Lieutenant Hubert C. G. Pedler resigns his commission, dated May 28, 1913. _Ernest Deane Anderson to 'be Surgeon. Lieutenant, vice H. C. G. Pedler, resigned, dated June 4, 1918. ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas E. Noding is placed on retired pay, dated May 25, 1913. http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ Lieutenant-Colonel Noding entered the Service as a Surgeon, Army Medical Depart ment, July 30, 1881; became Surgeon-Major, Army Medical Staff, July 30, 1893; Lieutenant·Colonel; Royal Army Medical Oorps, July 30, 1901; Lieutenant·Colonel with increased pay, April 19,1907. His war service is: Egyptian Expedition, 1882. Medal; bronze star. Waziristan Expedition, 1894·95. Medal with clasp. The undermentioned Majors to be Lieutenant·Colonels: Charles Dalton vice J. -

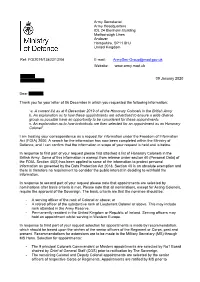

Information Regarding the Appointment of All Honorary Colonels in the British Army

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: FOI2019/13423/13/04 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk XXXXXX 09 January 2020 xxxxxxxxxxxxx Dear XXXXXX, Thank you for your letter of 06 December in which you requested the following information: “a. A current list as at 6 December 2019 of all the Honorary Colonels in the British Army b. An explanation as to how these appointments are advertised to ensure a wide diverse group as possible have an opportunity to be considered for these appointments c. An explanation as to how individuals are then selected for an appointment as an Honorary Colonel” I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm that the information in scope of your request is held and is below. In response to first part of your request please find attached a list of Honorary Colonels in the British Army. Some of this information is exempt from release under section 40 (Personal Data) of the FOIA. Section 40(2) has been applied to some of the information to protect personal information as governed by the Data Protection Act 2018. Section 40 is an absolute exemption and there is therefore no requirement to consider the public interest in deciding to withhold the information. In response to second part of your request please note that appointments are selected by nominations after basic criteria is met. -

2846 Supplement to the London Gazette, 15Th March 1966

2846 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 15TH MARCH 1966 ROYAL CORPS OF TRANSPORT LIGHT INFANTRY BRIGADE Maj. R. G. PLAISTER, T.D. (339198). Hereford LJ. ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS Capt. (A/Maj.) J. W. de M. JEFFREY (438550). Bt. Maj. J. KILSHAW, M.B.E., T.D. (386089). YORKSHIRE BRIGADE WOMEN'S ROYAL ARMY CORPS F. & L. Maj. C. T. DYER, T.D. (388243). Capt. R. F. W. BAKER (422242). MERCIAN BRIGADE The QUEEN has been graciously pleased to confer Cheshire the award of the Territorial Efficiency Decoration Maj. M. G. HOLLOWAY (440626). upon the following officers: NORTH IRISH BRIGADE ROYAL ARMOURED CORPS R.U.R. SJI.Y. Capt. (A/Maj.) I. B. GAILEY (439851). Maj. R. E. BANKS (445319). HIGHLAND BRIGADE K C L Y A. & SJI. 'Capt. (A/Maj.) C. D. VOELCKER (422358). Maj. F. S. SMITH (425463). N.I.H. Maj. W. ALLEN (379304). ROYAL ARMY CHAPLAINS' DEPARTMENT Capt. P. F. S. CLEMENTS (435880). Rev. A. C. V. MENZIES (205975) (C.F. 3rd. Cl.). Capt. J. M. LANGHAM (435888). ROYAL ARMY SERVICE CORPS ROYAL REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY Lt. (Hon. Capt.) B. H. EDWARDS (76029) now Lt.-Col. J. FRENCH (166316). T.A.R.O. Maj. C. C. MARSHALL (436173). ROYAL CORPS OF TRANSPORT Maj. (Hon. Lt.-Col.) E. R. ORME (27489). Lt.-Col. J. D. MORRISON (160634). Maj. T. THOMPSON (411842). Capt. C. J. LAST (425183). Capt. (Hon. Maj.) H. BAKER (57396) retired. Capt. (A/Maj.) A. W. BARDSLEY (416222). ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS Capt. (Hon. Maj.) S. A. LIVITT (70921) retired. Lt.-Col. O. H. BLACKLAY, M.B.