How Boise Might Help Save the 'Last Uni...D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Saola Or Spindlehorn Bovid Pseudoryx Nghetinhensis in Laos

ORYX VOL 29 NO 2 APRIL 1995 The saola or spindlehorn bovid Pseudoryx nghetinhensis in Laos George B. Schaller and Alan Rabinowitz In 1992 the discovery of a new bovid, Pseudoryx nghetinhensis, in Vietnam led to speculation that the species also occurred in adjacent parts of Laos. This paper describes a survey in January 1994, which confirmed the presence of P. ngethinhensis in Laos, although in low densities and with a patchy distribution. The paper also presents new information that helps clarify the phylogenetic position of the species. The low numbers and restricted range ofP. ngethinhensis mean that it must be regarded as Endangered. While some admirable moves have been made to protect the new bovid and its habitat, more needs to be done and the authors recommend further conservation action. Introduction area). Dung et al. (1994) refer to Pseudoryx as the Vu Quang ox, but, given the total range of In May 1992 Do Tuoc and John MacKinnon the animal and its evolutionary affinities (see found three sets of horns of a previously un- below), we prefer to call it by the descriptive described species of bovid in the Vu Quang local name 'saola'. Nature Reserve of west-central Vietnam The village of Nakadok, where saola horns (Stone, 1992). The discovery at the end of the were found, lies at the end of the Nakai-Nam twentieth century of a large new mammal in a Theun National Biodiversity Conservation region that had been visited repeatedly by sci- Area (NNTNBCA), which at 3500 sq km is the entific and other expeditions (Delacour and largest of 17 protected areas established by Jabouille, 1931; Legendre, 1936) aroused in- Laos in October 1993. -

I Vividly Remember Reading About the Discovery of the Saola (Pseudoryx

I vividly remember reading about the discovery of the Saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) in the BBC Wildlife Magazine whilst sitting in my traditional English school library. I was transfixed by the discovery of a distinctive, one-and-a-half-meter long, 70 kilogram ungulate with long tapered horns in the forests of Vietnam. I vowed there and then to work on and help the species however I could. Twenty-six years later I am still keeping that vow, but time is running out. It is going to take an incredible effort to stave off extinction and put the Saola on the path to recovery toward a fully functioning population. The discovery of the Saola in 1992 has been heralded as one of the most spectacular zoological discoveries of the 20th century, not only because of the size and beauty of the species, but also because of its phylogenetic distinctiveness; the Saola sits alone in a monotypic genus. Its morphological and genetic characteristics suggest it is a primitive member of the tribe Bovini, along with the cattle and buffalo, within the family Bovidae. The Saola is found in the North and Central Annamite Mountains of Vietnam and Laos where it is restricted to climatically wet evergreen, broadleaf forest habitats. These forests are subjected to an up to 10-month long rainy season, with no month receiving less than 40 mm of rain. This level of rainfall is the result of two monsoons, and determines the Saola’s distribution. The western and southern distribution of the Saola are bounded by the rain shadow of mountain chains with the western extent expanding deeper into Laos where the mountains dip, allowing deeper penetration of the northeast winter monsoon. -

242-243244-245

Index │242-243244-245 88551 White Lion Cub - Walking 089 88824 African Civet 090 88681 Spotted Seal Pup 134 88554 Red River Hog 086 88829 Père David's Deer 097 88710 South African Penguin 127 88001 Red Fox 110 88560 Brown Bear 105 88830 Common Zebra 091 88726 Blacktip Reef Shark 125 88002 Rabbit 111 88561 Brown Bear Cub 105 88831 Ring-Tailed Lemur 080 88729 Great White Shark - Open Jaw 121 88003 Barn Owl 110 88562 Waterbuck 086 88832 White-Tailed Deer 112 88761 Blainville's Beaked Whale 130 88012 Brown Hare 111 88563 Giant Eland Antelope 084 88833 Hippopotamus 087 88765 Wandering Albatross 127 88015 Eurasian Badger 111 88564 Giant Sable Antelope Male 085 88837 Musk Ox 113 88766 Dugong 126 88025 African Elephant 085 88565 Lynx 097 88844 Timber Wolf Howling 113 88788 124 88026 African Elephant Calf 085 88566 Striped Hyena 082 88845 Timber Wolf Hunting 114 88804 120 88053 Common Otter 110 88578 Giant Sable Antelope Female 084 88850 Zebra Foal 091 88806 Leopard Seal 134 88089 White Rhinoceros Calf 090 88595 Maned Wolf 116 88852 White Rhinoceros 091 88834 Blue Whale 130 88090 Hippopotamus Calf 087 88596 Baird's Tapir 116 88859 Porcupine 096 88835 Sperm Whale 130 88166 Giant Panda 104 88597 Tapir Calf 116 88865 Dama Gazelle 090 88836 Gray Whale 128 88167 Giant Panda Cub - Standing 104 88602 Przewalski Stallion 096 88866 African Leopard 090 88851 King Crab 124 88204 Baboon Male 088 88604 Dartmoor Pony Bay 110 88881 Malayan Tapir 098 88862 Minke Whale 129 88207 Flamingo 118 88607 Fennec Fox 083 88890 Black Leopard 091 88895 126 88208 Dromedary -

Appetite for Destruction (Summary Report)

APPETITE FOR DESTRUCTION SUMMARY REPORT © RUDOLF SVEN 2 APPETITE FOR DESTRUCTION S ON / WW EXECUTIVE SUMMARY F Food is at the heart of many of the issues WWF focuses on. Through our work on sustainable diets, we know a lot of people are aware of the impact a meat-based diet has on water, land and habitats, and the implications of its associated greenhouse gas emissions. But few know the largest impact comes from the crop- based feed the animals eat. In a world where more and more people adopt a Western diet – one that’s high in meat, dairy and processed food – producing crops to feed our livestock is putting an enormous strain on our natural resources and is a driving force behind wide-scale biodiversity loss. The UK food supply alone is directly linked to the extinction of an estimated 33 species at home and abroad. WWF’s vision of a future where people and nature thrive is threatened by this current food system. This report looks at the impacts our appetite for animal protein – and in particular the associated hidden impacts of animal feed – has on our planet. We focus on the production of soy as feed for chicken, pork and fish and the consequences this has for the environment. We link the increased use of feed to the reduced nutritional value of these animal products, before exploring solutions through changing diets and alternative feed production systems. THE UK FOOD SUPPLY ALONE IS DIRECTLY LINKED TO THE extinction OF AN ESTIMated 33 SPECIES at HOME AND ABROAD © ALFFOTO © T OM V 7 A N L IMPT/HOLL A ND S E HOOGTE/L FOOD, FEED AND BIODIVERSITY Rarely a week goes by without a headline about the negative effects of meat on our health or our environment. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

How Your Change, Changes the World

17 1 17 17 17 1 31 17 11 11 14 22 30 23 25 15 20 24 13 14 6 19 29 5 8 12 11 How your 2 9 13 18 28 16 change, 27 26 32 11 changes 7 4 11 4 21 3 11 the world 10 11 2011-2015 Projects Supported by Quarters for Conservation United States (1.) Sea Turtles Africa Africa (cont) 17. Snow Leopard • China, India, Central and South America University of Central Florida Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Pakistan 24. Iguanas • Honduras Butterflies 2. Chimpanzee & Western Lowland 10. Cheetah • South Africa Snow Leopard Trust International Iguana Foundation Florida Butterfly Swallow-tailed Kite Gorilla • Republic of the Congo Cheetah Outreach Monitoring Network Goualougo Triangle Ape Project Avian Research and 18. Slow Loris • Indonesia/Java 25. Guatemalan Wildlife • Guatemala Conservation Institute Little Fireface Project ARCAS Guatemala Coral 3. Cheetah • Namibia Africa/Asia Environmental Department Coral Restoration Cheetah Conservation Fund Atala Butterfly 11. Rhinoceros • Indonesia, India, 19. Sea Turtles • Sri Lanka Foundation Brevard Zoo Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa, Sri Lanka Turtle Conservation Project 26. Amphibians • Bolivia 4. African Carnivores • Botswana Swaziland, Vietnam Bolivian Amphibian Initiative Dolphin and Namibia East Coast International Rhino Foundation 20. Pangolin • Vietnam Sarasota Dolphin African Predator Conservation Diamondback Terrapin Save Vietnam’s Wildlife Pangolin 27. Giant Armadillo • Brazil Research Project Research Organization and Brevard Zoo Conservation Program Pantanal Giant Armadillo Project Cheetah Conservation Fund Asia Florida Grasshopper Sparrow Florida Scrub-Jay 28. Tapirs • Brazil Kissimmee Prairie Preserve’s 5. Western Lowland Gorillas • Brevard Zoo 12. Orangutan • Indonesia/Sumatra Australia The Lowland Tapir Conservation Citizen Support Organization Republic of Congo Rainforest Rescue 21. -

Zsl Conservation Review 2013 3 Zsl Conservation Review / Where We Work

ZSL Conservation Review Review Conservation ZSL CONSERVATION REVIEW 2013 2013 The Zoological Society of London Registered Charity in England and Wales: no 208728 zsl.org Regent’s Park London NW1 4RY and at: ZSL Whipsnade Zoo Dunstable Bedfordshire LU6 2LF For a closer look at ZSL’s work, look out for our other annual publications at zsl.org/about-us/annual-reports ZSL The Year in Review 2013 ZSL Institute of Zoology Our annual overview of the year, Review 2012/13 featuring our zoos, fieldwork, All our research activities, science, engagement activities collaborations, publications and and ways to get involved. funding in one yearly report. OUR VISION: OUR MISSION: A world where animals To promote and achieve the are valued, and their worldwide conservation of conservation assured animals and their habitats ZSL CONSERVATION REVIEW / WELCOME Welcome The President and Director General of the Zoological Society of London look back on some of 2013’s conservation highlights. As President of the Zoological Society of London Last year, ZSL was involved in several initiatives that are (ZSL), my role is to ensure that the Society is transforming the field of conservation. We continued achieving its ambitious mission: “To promote and to lead in defining the status and trends of the world’s achieve the worldwide conservation of animals and species and ecosystems through our Indicators and their habitats.” During 2013, ZSL made major progress Assessments Unit, while our conservation technology in this direction. Significant advances were achieved team is developing remote monitoring units that in monitoring the status of the planet; developing are revolutionising the way we keep track of species, new conservation technology; conserving one-of-a-kind species on conduct surveillance and communicate conservation to the public. -

The Saola's Battle for Survival on the Ho Chi Minh Trail

2013 THE SAOLA’S BAttLE FOR SURVIVAL ON THE HO CHI MINH TRAIL © David Hulse / WWF-Canon WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced independent conservation organizations, with over 5 million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s biological diversity, ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. Written and edited by Elizabeth Kemf, PhD. Published in August 2013 by WWF – World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund), Gland, Switzerland. Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © Text 2013 WWF All rights reserved. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. SAOLA SPAWNS DECADES OF SPECIES DISCOVERIES 7 3. THE BIG EIGHT OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY 9 4. THREATS: TRAPPING, ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE AND HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 11 5. TUG OF WAR ON THE HO CHI MINH TRAIL 12 6. DISCOVERIES AND EXTINCTIONS 14 7. WHAT IS BEING DONE TO SAVE THE SAOLA? 15 Forest guard training and patrols 15 Expanding and linking protected areas 16 Trans-boundary protected area project 16 The Saola Working Group (SWG) 17 Biodiversity surveys 17 Landscape scale conservation planning 17 Leeches reveal rare species survival 18 8. THE SAOLA’S TIPPING POINT 19 9. TACKLING THE ISSUES: WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE? 20 Unsustainable Hunting, Wildlife Trade And Restaurants 20 Illegal Logging And Export 22 Dams And Roads 22 10. -

Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION RECOGNITION The family Bovidae, which includes Antelopes, Cattle, Duikers, Gazelles, Goats, and Sheep, is the largest family within Artiodactyla and the most diverse family of ungulates, with more than 270 recent species. Their common characteristic is their unbranched, non-deciduous horns. Bovids are primarily Old World in their distribution, although a few species are found in North America. The name antelope is often used to describe many members of this family, but it is not a definable, taxonomically based term. Shape, size, and color: Bovids encompass an extremely wide size range, from the minuscule Royal Antelope and the Dik-diks, weighing as little as 2 kg and standing 25 to 35 cm at the shoulder, to the Asian Wild Water Buffalo, which weighs as much as 1,200 kg, and the Gaur, which measures up to 220 cm at the shoulder. Body shape varies from relatively small, slender-limbed, and thin-necked species such as the Gazelles to the massive, stocky wild cattle (fig. 1). The forequarters may be larger than the hind, or the reverse, as in smaller species inhabiting dense tropical forests (e.g., Duikers). There is also a great variety in body coloration, although most species are some shade of brown. It can consist of a solid shade, or a patterned pelage. Antelopes that rely on concealment to avoid predators are cryptically colored. The stripes and blotches seen on the hides of Bushbuck, Bongo, and Kudu also function as camouflage by helping to disrupt the animals’ outline. -

Application of Genome Assembly to Bovidae Species

Application of genome assembly to Bovidae species Tim Smith U.S. Meat Animal Research Center Clay Center, Nebraska September 20, 2018 PacBio User Group Meeting St. Louis, MO AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE is an equal opportunity provider and employer U.S. Meat Animal Research Center Clay Center, Nebraska 8 mi (11 km) Science complex 7800 breeding cows/heifers 800 swine litters/year 2000 breeding ewes The Bovinae Family Tree Branch lengths are not proportional to time (From Hernandez-Fernandez and Vrba, 2005) Nilgai (India) Four-horned antelope, Chousingha (India) Lesser kudu (Ethiopia) Nyala (South Africa) Bushbuck (Senegal) Sitatunga (Tanzania) Bongo (West Africa) Greater kudu (South Africa) Mountain Nyala (Ethiopia) Giant eland (Gambia) Common eland (South Africa) Saola (Laos) African Buffalo Domestic Water Buffalo, Bubalus Bubalis Tamaraw (Mindoren island, Phillipines) Lowland anoa (Indonesia) Mountain anoa (Phillipines) Gaur (Bangladesh) Banteng (Indonesia, Java) Kouprey (Cambodia) Progenitor of Bos taurus Yak (Boreal Asia; also Bos grunniens) American Bison (North America) Wisent (Poland) The Bovinae Family Tree Branch lengths are not proportional to time (From Hernandez-Fernandez and Vrba, 2005) Nilgai (India) Four-horned antelope, Chousingha (India) Lesser kudu (Ethiopia) Nyala (South Africa) Bushbuck (Senegal) Sitatunga (Tanzania) Bongo (West Africa) Greater kudu (South Africa) Mountain Nyala (Ethiopia) Giant eland (Gambia) Common eland (South Africa) Saola (Laos) African Buffalo Domestic Water Buffalo, Bubalus Bubalis Tamaraw (Mindoren island, Phillipines) Lowland anoa (Indonesia) Mountain anoa (Phillipines) Gaur (Bangladesh) Banteng (Indonesia, Java) Kouprey (Cambodia) Progenitor of Bos taurus Yak (Boreal Asia; also Bos grunniens) American Bison (North America) Wisent (Poland) Cave painting of Aurochs ca. 14,000 BC Aurochs drawing ca. -

ENDANGERED (EN) Yangtze River Dolphin: CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR/PE) Amazon River Dolphin: VULNERABLE (VU) Tucuxi: Data Deficient (DD) Www

www. wwfthai. Wildlife in the Tropical org Wetlands Dr. Chavalit Vidthayanon Senior Freshwater Biologist WWF Greatermekong Thailand www. wwfthai. org •Example of wetland wildlife cases • Freshwater dolphins • Dugong • Wetland dependent mammals • Amphibians • Freshwater & Sea turtles • Aquatic reptiles www. wwfthai. org Keystone-Flagship species samples Mekong basin: Giant catfish, big fishes, Irrawaddi dolphin Central plains: big fishes, stingrays, croc. Coastal : Cetacea, sharks and rays Peat swamp forests: Stenotopic fishes, croc. Seagrass beds: dugong, dolphins, fishes Lagoon and Lake: Irrawaddi dolphin, sharks and rays www. wwfthai. แหลงอาศัยของสัตวปา org Critical Species and Habitats • Endangered aquatic mammals – Irrawaddi dolphin : Mainstreams, lagoons – Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin: Coastal waters – Smooth-coated otter: forested streams – Hairy-nosed otter: peatswamps – Dugong: seagrasses • Endangered aquatic Reptiles – จระเขน้ําจืด Siamese Crocodile: flooded forests – มานลาย Giant softshell turtle: river sand dunes – เตากระอาน Batagur baska: lowland rivers, estuaries www. wwfthai. Mekong Wetlands as Bird Habitats and org Birding Sites • Over 300 species of Migratory Birds • นกใกลสูญพันธุของโลก Globally threatened waterbirds – กระเรยนี Eastern sarus crane – นางนวลแกลบทองดํา Black-bellied tern – นางนวลแกลบแมน้ํา Indian river tern – กระแตผียักษ Great thick-knee – Giant ibis – White-shouldered ibis • Endemic birds – Mekong wagtail – Mekong Bengal florican www. wwfthai. org Globally Threatened Waterbirds Wetland dependentwww. mammals wwfthai. org Flathead cat: Endangered Otter civet Baycat: Endangered Giant otter Hairy-nosed otter www. wwfthai. org Saola: EN Asian Rhinos: EN to Critical Asian Mega fauna Wild buffalos www. wwfthai. Asian Mega fauna org Eld’s deer Pere david’s deer Barasinga Asian tapir www. wwfthai. org Critically Endangered: CR Indochinese hogdeer Axis porcinus annamiticus www. wwfthai. org Neotropic Rain Forest Wetlands Congo Rain Forest Wetlands www. -

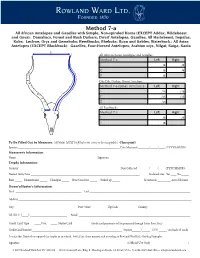

Rowland Ward Ltd. R

D WA AN RD L L W T D O . ROWLAND WARD LTD. R F 0 FOUNDED 1870 O 7 U 8 N DE D 1 Method 7-a All African Antelopes and Gazelles with Simple, Non-spiraled Horns (EXCEPT Addax, Wildebeest and Gnus): Damaliscs, Forest and Bush Duikers; Dwarf Antelopes; Gazelles; All Hartebeest; Impalas; Kobs; Lechwe; Oryx and Gemsboks; Reedbucks; Rheboks; Roan and Sables; Waterbuck.; All Asian Antelopes (EXCEPT Blackbuck): Gazelles, Four-Horned Antelopes; Arabian oryx, Nilgai; Saiga; Saola E L All African/Asian Antelopes and Gazelles Method 7-a Left Right L /8 /8 C /8 /8 E /8 Dik-Dik, Duiker, Dwarf Antelope Method 7-a (Small Antelopes) Left Right L /16 /16 C /16 /16 E /16 C All Reedbucks L Method 7-a Left Right L /8 /8 E /8 To Be Filled Out by Measurer: (All fields MUST be filled in for entry to be acceptable.) (Please print!) Species ______________________________________________________________ Date Measured _______/_____/____ (YYYY/MM/DD) Measurer’s Information: Name __________________________________________________ Signature __________________________________________________ Trophy Information: Country _______________________________________________________________ Date Collected _______/_____/____ (YYYY/MM/DD) Nearest town/Area ____________________________________________________________________ Enclosed area: Yes ____ No _____ Rifle _____ Muzzleloader _____ Handgun _____ Bow/Crossbow _____ Picked up _____ If enclosed, _________ Acres/Hectares Owner’s/Hunter’s Information: First _________________________________________ Last _______________________________________________________________