Nantwich 1644

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A500 Dualling) (Classified Road) (Side Roads) Order 2020

THE CHESHIRE EAST BOROUGH COUNCIL (A500 DUALLING) (CLASSIFIED ROAD) (SIDE ROADS) ORDER 2020 AND THE CHESHIRE EAST BOROUGH COUNCIL (A500 DUALLING) COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 2020 COMBINED STATEMENT OF REASONS [Page left blank intentionally] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of Statement ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Statutory powers ............................................................................................................... 2 2 BACKGROUND AND SCHEME DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................... 3 2.1 Regional Growth ................................................................................................................ 3 2.2 Local Context ..................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Scheme History .................................................................................................................. 5 3 EXISTING AND FUTURE CONDITIONS ........................................................................................ 6 3.1 Local Network Description ................................................................................................ 6 3.2 Travel Patterns ............................................................................................................... -

Che:3Hire. Lis~Ard

DIR~CTvRY.] CHE:3HIRE. LIS~ARD. 417 enlarged in 1913: an ancient alt.ar cros3, hammered in who by will, dated 1736, in the event of the death of John err.bossed brass, was the gift of Edward Henry Loyd i Harrison, an infant, without issue, left his estate to Mrs. esq. Col. C. H. France-Hayhurst, ef Eostock Hall, a~d I Ann Smith, of Berkeley square, London: according t.o their wives, in 1904: the church affords 230 sittings. Ormerod, the historian of Cheshire, this lady bequeathed The register dates from the year 1849. The living is p. the estate to William Pulteney, Earl of Bath, whose heir vicarage, net yelTly value £202, with residence, in the and brother, Lieut.-General Henry Pulteney, died in 1767, gift of the Bishop of Chester, and held since 1902 by leaving the Bradford estates to his oousin Frances Pulteney, th~ Rev. Robert James Douglas Keith-Chalmers B.A. wife of William Johnstone esq. who thereupon took the of the University of London; the vicarage, adjoining the name of Pulteney, and succeeding his brother in 1794 in church, is a building in the Elizabethan style. The soil the baronetcy of Johnstone, of Westerhall, became Sir is principally clay, also the subsoil. Nearly all the land William Johnstone-Pulteney bart.: on his death, in 1805, is pasture, and cheese is made about here. The area is Minshull Vernon passed to William Henry (Vane) grd Earl 3,903 acres; the population of the ecclesiastical parish of Darlington,and in 1812 his lordship sold the manor,with in 1911 was 424. -

Hurleston Business Park, Hurlestson, Nantwich, Cheshire

INDUSTRIAL • • WORKSHOP/STORAGE/OFFICE SECURE SITE • • HARDSTANDING PROMINENT ROAD SIDE FRONTAGE • • 27,729 SQ FT ON A SITE OF 5.5 ACRES EA LICENSED (MAY SUBDIVIDE) Hurleston Business Park, Hurlestson, Nantwich, Cheshire. CW5 6BU LOCATION ACCOMMODATION SCHEDULE Hurleston Business Park is located between the M6 and North Wales and just 2 miles from Cheshire’s newest major industrial Park at Cheshire Green. DESCRIPTION SQ FT SQ FT EAVES • 3 miles to Nantwich Two storey workshop/storage 5,693 528.90 6.0 • 6 miles to Crewe • 17 miles to Chester Workshop 696 64.70 3.0 • 11 miles to Junction 16 of the M6 Workshop 5,560 516.60 5.5 DESCRIPTION Open Sided Storage 3,877 360.2 3.5 The site comprises a combination of workshop, storage and office accommodation surrounded by concrete hardstanding with a low site density of only 11.5% Storage 2,897 269.20 3.5 The site also benefits from excellent road frontage and secure perimeter fencing and has previously been used for retail vehicles and recycling. Open Sided Storage 998 92.80 2.5 Sub division of the site may be considered Mess/Staff Room 399 37.10 TERMS Price upon application Workshop 3,055 283.80 2.2 Workshop 1,013 94.20 3.0 ENERGY PERFORMANCE CERTIFICATE The premises have an EPC rating of Office 1,825 169.60 UTILTIES Two Storey Office 1,716 159.5 The site is connected to private drainage and three phase electricity TOTAL GIA 27,729 2576.60 PLANS/PHOTOGRAPHS Site Area 5.5 acres 2.2 hectares Any plans or photographs that are forming part of these particulars were correct at the time of preparation and it is expressly stated that they are for reference rather than fact. -

A Walk from Church Minshull

A Walk to Church Minshull Aqueduct Marina photo courtesy of Bernie Stafford Aqueduct Marina, the starting point for this walk, was opened in February 2009. The marina has 147 berths, a shop and a café set in beautiful Cheshire countryside. With comprehensive facilities for moorers, visiting boaters and anyone needing to do, or have done, any work on their boat, the marina is an excellent starting point for exploring the Cheshire canal system. Starting and finishing at Church Minshull Aqueduct Marina, this walk takes in some of the prettiest local countryside as well as the picturesque village of Church Minshull and the Middlewich Branch of the Shropshire Union Canal. Some alternative routes are also included at the end to add variation to the walk which is about five or six miles, depending on the exact route taken. Built to join the Trent and Mersey Canal with the Chester Canal, the Middlewich Branch carried mainly coal, salt and goods to and from the potteries. Built quite late in the canal building era, like so many other canals, this canal wasn’t as successful as predicted. Today, however, it is a very busy canal providing an essential link between the Trent and Mersey Canal at Middlewich and the Llangollen Canal as well as being part of the Four Counties Ring and linking to the popular Cheshire Ring boating route. The Route Leaving the marina, walk to the end of the drive and turn north (right) onto the B5074 Church Minshull road and walk to the canal bridge. Cross the canal and turn down the steps on the right onto the towpath, then walk back under the bridge, with the canal on your left. -

The Story of the 1986 Domesday Project

The Story of the 1986 Domesday Project In 1986, 900 years after William the Conqueror’s original Domesday Book, the BBC published the Domesday Project . The project was probably the most ambitious attempt ever to capture the essence of life in the United Kingdom. Over a million people contributed to this digital snapshot of the country. People were asked to record what they thought would be of interest in another 1000 years. The whole of the UK was divided into 23,000 4x3km areas called Domesday Squares or “D- Blocks”. Church Minshull was d-block 364000-360000. Schools and community groups surveyed over 108,000 square km of the UK and submitted more than 147,819 pages of text articles and 23,225 amateur photos, cataloguing what it was like to live, work and play in their community. Website address: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/domesday/dblock/GB-364000-360000 The project was about documenting everyday life - the ordinary, rather than the extraordinary and residents of Church Minshull in 1986, responded with their written accounts… The categories below contain the Church Minshull snapshot of life in 1986… The Village Church Minshull is a village situated at a bend in the R. Weaver. It was called Maneshale (Old English = nook or corner) in the first Domesday book. The village is the centre of the area in which agriculture, mainly dairy farming, is the principle industry. There are 286 people on the electoral role, the main centres of population being the village and the mobile home site at Lea Green. So far, there are not too many commuters living here, but there has been a noticeable increase in the turn-over of property in the last five years. -

24047-Slipways-In-Llangollen-Canal

Trailable and Portable boat launching locations North Wales & Borders Llangollen Canal Author: Derek Smith We would like to thank Derek for kindly putting this information together for waterway visitors As the information was provided by a third party we cannot guarantee or warrant its completeness or accuracy and accordingly the Trust does not accept any liability for any inaccuracy or omission in the information provided Launching Place Grades Slipways & Access (Blue numbers: - For large boats on trailers that need slipways) 1. Excellent. For 2.3 Mts and wider trailers. Slipways1.2+ Mts deep at the wet end. 2. Good. For 2.3 Mts wide trailers. Slipways 60 cm to 1 Mtr deep at the wet end. 3. Adequate. For 2.3 Mts wide trailers. The slipway has features requiring very skilful reverse driving, or could have severe launching or retrieving difficulties. 4. Poor. Narrow slipway or shallow at the end. For trailers less than 2.3 Mts wide; or less than 60 cm deep at the wet end. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Landing Places & Access (Green numbers: - For boats on roof-racks or trailers that don’t need slipways) 1. Excellent. For launching all types of portable boats from Kayaks to RIB’s with strong crews. 2. Good. For launching kayaks, canoes, small inflatables and sometimes very small dinghies. 3. Adequate. For launching kayaks and canoes. 4. Poor. For launching kayaks only. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Parking (Blue or green letters: - For cars, minibuses & trailers) a. Excellent. Mainly long term booked car parking for vehicles & trailers. Normally has good supervision and spare space. Enclosed and has gates or a barrier and is very secure. -

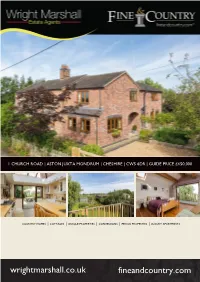

Wrightmarshall.Co.Uk Fineandcountry.Com

1 CHURCH ROAD | ASTON JUXTA MONDRUM | CHESHIRE | CW5 6DR | GUIDE PRICE £450,000 COUNTRY HOMES │ COTTAGES │ UNIQUE PROPERTIES │ CONVERSIONS │ PERIOD PROPERTIES │ LUXURY APARTMENTS wrightmarshall.co.uk fineandcountry.com 1 Church Road, Aston Juxta Mondrum, Cheshire, CW5 6DR A beautifully presented four bedroom, three bathroom semi detached country cottage, substantially extended (approx 1856 sq ft N.I.) and tastefully restored and modernised. The property occupies a convenient position in a rural location, along a country lane and enjoys idyllic views to the front and rear. Briefly comprising: Open Porch, Reception Hall, Living Dining Room with fireplace, Kitchen/Breakfast Room with Atrium roof light, Morning/Laundry Room, Shower/WC. First Floor Landing, Master Bedroom One with external Balcony and Ensuite Bathroom, Bedroom Two, Bedroom Three, Bedroom Four, Family Bathroom. Delightful herbaceous cottage style landscaped gardens with Indian stone hard landscaping and driveway/parking. DIRECTIONS NANTWICH (3 MILES) Proceed from the Agent's Nantwich Office along Hospital Street to the Nantwich is a charming market town set beside the River Weaver with mini roundabout. Continue to the next roundabout (Church Mansion) a rich history, a wide range of speciality shops and 4 supermarkets. and turn left. Proceed over onto Millstone Lane to the traffic lights. Nantwich in Bloom in November 2015 was delighted to have once Continue onto Barony Road passing 'Hobsons Choice'. Go straight again scooped the prestigious Gold award from the Britain in Bloom ahead at the traffic lights. When you reach the roundabout take the competition. In Cheshire, Nantwich is second only to Chester in its 2nd exit (signed B5074) to Worleston Village. -

Prime Accommodation Land Chester Road, Hurleston

LAND FOR SALE PRIME ACCOMMODATION LAND At CHESTER ROAD, HURLESTON, NANTWICH, CW5 6BU. Extending to 1.432 Acres For Sale by Private Treaty Guide Price: £20,000 Plus Auctioneers: Solicitors: Wright Marshall Hibberts LLP Beeston Castle Auction 25 Barker Street Whitchurch Road, Beeston Nantwich Tarporley CW6 9NZ CW5 5EN Tel: 01829 262 132 Tel: 01270 624 225 Location: The land is located on the A51 Trunk Road at Hurleston, Chester Side of the Waterworks. See Location Plan foe exact position or the Sale Board. Description: A small parcel of grassland extending to 1.432 Acres formed when the A51 Road Improvement Scheme was implemented some years ago. It was originally part of Yew Tree Farm, (Now the Equestrian Vets) on the opposite side of the road. It has a medium loam soil, is in grass and being used currently as a Pony Paddock. The Horse Shelter and Horse Fencing are specifically EXCLUDED from the sale. There is a 14 foot gate into the field from the original A51 carriageway adjacent to the drive end to Hill Farm. The boundaries comprise a thick tall mature hedge against the old main road, now a private lane and a post and rail fence along the current road. A metered mains water is supplied to a drinking trough. See photograph. Title: The field has registered Freehold Title. Tenure: Vacant Possession available on completion. The Horse Grazier being a friend of the Vendor will vacate when requested. Basic Payment Scheme: No B.P.S. Entitlements included with the sale of the land. Local Authorities: Cheshire West & Chester Council, 58 Nicholas Street, Chester, CH1 2NP. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No.391 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No.391 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Nicholas Morrison KCB DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin MEMBERS Lady Bowden Mr J T Brockbank Mr R R Thornton CBE. DL Mr D P Harrison Professor G E Cherry To the Rt Hon William Whitelaw, CH MC MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR THE FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COUNTY OF CHESHIRE 1. The last Order under Section 51 of the Local Government Act 1972 in relation to the electoral arrangements for the districts in the County of Cheshire was made on 28 September 1978. As required by Section 63 and Schedule 9 of the Act we have now reviewed the electoral arrangements for that county, using the procedures we had set out in our Report No 6. 2. We informed the Cheshire County Council in a consultation letter dated 12 January 1979 that we proposed to conduct the review, and sent copies of the letter to the district councils, parish councils and parish meetings in the county, to the Members of Parliament representing the constituencies concerned, to the headquarters of the main political parties and to the editors both of » local newspapers circulating in the county and of the local government press. Notices in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies. 3» On 1 August 1979 the County Council submitted to us a draft scheme in which they suggested 71 electoral divisions for the County, each returning one member in accordance with Section 6(2)(a) of the Act. -

A500 Dualling Draft Final – with Cover

A500, M6 to A5020 DfT Large Local Major Transport Schemes Funding Bid B1832076/OD/013 Revision 0 July 2016 A500, M6 to A5020 Project No: B1832076 Document Title: DfT Large Local Major Transport Schemes Funding Bid Document No.: B1832076-OD-13 Revision: R0 Date: July 2016 Client name: Cheshire East Council Project manager: Dan Teasdale Author: Rob Minton File name: Large Local Transport Schemes_A500 Dualling_Draft Final – with cover Jacobs U.K. Limited © Copyright 2016 Jacobs U.K. Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This report has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ Client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the Client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this report by any third party. Document history and status Rev Date Description By Review Approved R0 27/07/16 For submission R Minton A Curley D Teasdale Large Local Major Transport Schemes Application for Scheme Development Costs – Main Round Scheme Name A500 Dualling Lead LEP Cheshire and Warrington Local Enterprise Partnership Other supporting LEPs Stoke and Staffordshire Local Enterprise Partnership (if applicable - see 2.4 below) Promoting Authority Cheshire East Council Is this an update of a bid No that was unsuccessful in the fast track round 1. Introduction 1.1 Description Please describe the scheme (and attach a map if available) The A500 dualling scheme will upgrade a 3.2km section of the A500 from single carriageway to dual carriageway standard along with associated works to increase the capacity of the A500 / A531 / B5742 junction to the west. -

CHESHIRE. FAR 753 Barber William, Astbury, Congleton Barratt .Ambrose, Brookhouse Green, Ibay!Ey :Mrs

TRADES DlliECTORY. J CHESHIRE. FAR 753 Barber William, Astbury, Congleton Barratt .Ambrose, Brookhouse green, IBay!ey :Mrs. Mary Ann, The Warren, Barber William, Applet-on, Warrington Smallwo'Jd, Stoke-·on-Trent Gawsworth, Macclesfield Barber William, Buxton stoops. BarraH Clement, Brookhouse green, Beach J. Stockton Heath, Warrington Rainow, Macolesfield Sr.aallwood, Stoke-on-Trent Bean William, Acton, Northwich Barber W. Cheadle Hulme, Stockport Barratt Daniel. Brookhouse green, Beard· Misses Catherine & Ann, Pott; Bard'sley D. Hough hill, Dukinfield Smallwood, Stoke-on-Trent • Shrigley, Macclesfield Bardsley G. Oheadle Hulme, Stockprt Bal"''att J. Bolt's grn.Betchton,Sndbch Beard J. Harrop fold, Harrop,Mcclsfld Bardsley Jas, Heat<m Moor, Stockport Barratt Jn. Lindow common, :Marley, Beard James, Upper end, LymeHand- Bardsley Ralph, Stocks, :Kettleshulme, Wilmslow, Manchester ley, Stockport Macclesfield Barratt J. Love la. Betchton,Sand'bch Beard James, Wrights, Kettleshulme, Bardsley T. Range road, Stalybrid•ge Barratt T.Love la. Betchton, Sandb~h Macclesfield Bardsley W. Cheadle Hulme, Stckpri Barrow Mrs. A. Appleton, Warrington Beard James, jun. Lowe!l" end, Lyme Barff Arthnr, Warburton, Wa"flringtn Barrow Jn.Broom gn. Marthall,Kntsfd Handley, Stockport Barker E. Ivy mnt. Spurstow,Tarprly Ball'row Jonathan, BroadJ lane, Grap- Beard J.Beacon, Compstall, Stockport Barker M~. G. Brereton, Sandbach penhall, Warrington Beard R. Black HI. G~. Tascal,Stckpr1i Barker Henry, Wardle, Nantwich Barrow J. Styal, Handforth, )I'chestr Beard Samuel, High lane, StockpGri Barker Jas. Alsager, Stoke-upon-Trnt Barton Alfred, Roundy lane, .Adling- Be<bbington E. & Son, Olucastle, Malps Barker John, Byley, :Middlewich ton, :Macclesfield Bebbington Oha.rles, Tarporley Barker John, Rushton, Tall'porley Barton C.Brown ho. -

From Easter to Pentecost the Cross Country Parishes of Acton, Church Minshull, Wettenhall & Worleston

ST DAVID’S WETTENHALL & ST OSWALD’S WORLESTON MAY 2016 FROM EASTER TO PENTECOST THE CROSS COUNTRY PARISHES OF ACTON, CHURCH MINSHULL, WETTENHALL & WORLESTON ascended into A letter from the Ann heaven: 'Therefore go Dear Friends, and make disciples of all This month sees the 150th nations, anniversary of Reader Ministry. Back baptising them in 1866 Bishops gathered at in the name of Lambeth Palace on Ascension Day the Father and to create a body of ministers who of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and could make connections between a teaching them to obey everything I rapidly secularizing society and the have commanded you. And surely I Church. They were to form a bridge am with you always, to the very end between the clergy and the people. of the age.' These were the first Lay Readers. Obviously, of course, they were all Jesus' wonderful last words don't male. It wasn't until the 1960's that just apply to Readers however, or the first women were licensed to even clergy! They apply to everyone office. Now there are over 10,000 who believes in Him. Everyone can men and women exercising this play a part in bringing this about. Lay ministry throughout the Anglican ministry takes many different forms. Church. There are just under 500 We are so fortunate in our parishes Readers in Chester Diocese, one of to have people willing to put flowers the highest figures for a Diocese in in church, dust & polish, make tea, the Church of England. supply biscuits, provide cakes & sweets, clean gutters & grids, take So what is a Reader? Readers are out wheelie bins, cut grass, change licensed to preach, teach and lead altar frontals, act as Treasurers, worship.