Retrospective Adjustment of Alcohol Consumption Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

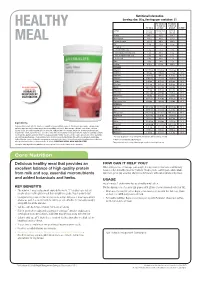

Formula 1 Factsheet

Title: Herbalife Products Made Simple FactSheets 2013 ID: MA790 HL 2013 PMS-Fact Sheets-Core Nutrition_UK-EI (1 of 5) Proof No: B Date: 23/07/13 Nutritional Information Serving size: 26 g, Servings per container: 21 Per 100 ml of Per 250 ml of made up of made up HEALTHY Per 100 g product* product* % RDA** Energy 375 kcal 88 kcal (370 221 kcal - (1579 kJ) kJ) (925 kJ) Protein 34.6 g 7.0 g 17.4 g - Carbohydrate 34.6 g 8.6 g 21.4 g - MEAL of which: sugars 32.7 g 8.4 g 20.9 g - Fat 8.8 g 2.6 g 6.4 g - of which: saturated fatty acids 1.9 g 1.1 g 2.8 g - mono-unsaturated fatty acids 1.2 g 0.6 g 1.4 g - poly-unsaturated fatty acids 5.8 g 0.6 g 1.6 g - linoleic acid 3.9 g 0.4 g 1.1 g - Fibre 9.6 g 1.0 g 2.5 g - Sodium 0.52 g 0.10 g 0.26 g - VITAMINS Vitamin A 1211.54 µg 139.39 µg 348.48 µg 44 % Vitamin D 9.62 µg 1.00 µg 2.50 µg 50 % Vitamin E 19.23 mg 2.04 mg 5.10 mg 42 % Vitamin C 57.69 mg 7.75 mg 19.38 mg 24 % Thiamin 1.08 mg 0.15 mg 0.38 mg 34 % Riboflavin 1.62 mg 0.35 mg 0.88 mg 63 % EXCLUSIVELY AVAILABLE Niacin 20.77 mg 2.25 mg 5.63 mg 35 % THROUGH YOUR Vitamin B6 1.92 mg 0.25 mg 0.62 mg 44 % HERBALIFE Folic Acid 230.77 µg 28.64 µg 71.59 µg 36 % INDEPENDENT Vitamin B12 1.92 µg 0.63 µg 1.58 µg 63 % DISTRIBUTOR Biotin 96.15 µg 13.60 µg 34.01 µg 68 % Pantothenic Acid 6.54 mg 1.00 mg 2.50 mg 42 % MINERALS Calcium 384.62 mg 161.54 mg 403.85 mg 50 % Iron 20.00 mg 2.13 mg 5.32 mg 38 % Phosphorous 657.69 mg 162.13 mg 405.33 mg 58 % Magnesium 92.31 mg 21.96 mg 54.90 mg 15 % Zinc 14.23 mg 1.86 mg 4.65 mg 47 % Iodine 153.85 µg 19.40 µg 48.50 µg 32 % -

Know Your Serving Size.Pub

KNOW YOUR SERVING SIZE Servings in restaurants, coffee shops and Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide supermarkets are getting larger and larger. identifies what a healthy serving size is It is no wonder why so many people are making it is easy to plan meals. confused about what a healthy serving size is. We are continuously bombarded with Figuring out the Food Guide servings will extra large servings such as super-size or take time. Measuring food is more accurate biggie size which appear to save us money. but is not always convenient. Estimating a However, in the long run, our bodies are Food Guide serving can be as simple as paying for it. As serving sizes grow so do using visual aides like the palm of your our waist lines! Knowing what a healthy hand, a tennis ball or golf ball. The serving serving size looks like will help you put an size guide will help you visualize a serving end to portion distortion. size. What more can I do? You don’t have to “clean your plate”... Also consider: Eating just so your plate is clean is an idea • Purchasing single portion snacks to that you should try to abandon. Start avoid eating more than one with smaller portions, pace yourself and • Eating snacks from a bowl instead of enjoy the taste of your food. Listen to out of a bag your body and stop when you feel • Having clean, cut up fruits or vegetables satisfied. Save the leftovers for the next ready in your fridge for snacking or day when you can enjoy the same great meals taste all over again. -

Food Label Tip: Watch Your Calories and Serving Sizes

Food Label Tip: Watch Your Calories and Serving Sizes It is important to watch your calories for weight control. To do this, you need to know how calories and serving size are related. This will help you choose foods and decide what amounts to eat or drink to keep a healthy weight. Learn about calories and serving size by looking at these food labels: Nutrition Facts Nutrition Facts Serving Size 1/2 cup (110g) Serving Size 1/2 cup (110g) Servings Per Container 3.5 Servings Per Container 3.5 Amount Per Serving Amount Per Serving Calories 50 Calories from Fat 0 Calories 100 Calories from Fat 0 % Daily Value* % Daily Value* Total Fat 0g 0% Total Fat 0g 0% Saturated Fat 0g 0% Saturated Fat 0g 0% In Fruit Juice Trans Fat 0g Trans Fat 0g In Heavy Syrup Cholesterol 0mg 0% Cholesterol 0mg 0% Sodium 25mg 1% Sodium 10mg 0% Total Carbohydrate 13g 4% Total Carbohydrate 24g 8% Dietary Fiber 1g 4% Dietary Fiber 1g 4% Sugars 9g Sugars 23g Protein less than 1g Protein 0g * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000 calorie diet. Vitamin A 8% Vitamin C 2% Vitamin A 2% Vitamin C 2% Your Daily Values may be higher or lower depending on Calcium 0% Iron 0% Calcium 0% Iron 0% your calorie needs. This is where you find the Here is where you find calories on a food label. There are “Serving Size” on a food label. 50 calories in 1 serving (1/2 cup) of canned peaches in The Serving Size for both types fruit juice. -

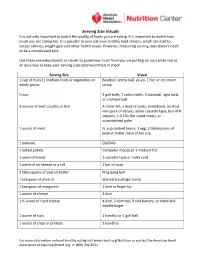

Serving Size Visuals It Is Not Only Important to Watch the Quality of Foods You Are Eating, It Is Important to Watch How Much You Are Eating Too

Serving Size Visuals It is not only important to watch the quality of foods you are eating, it is important to watch how much you are eating too. It is possible to over-eat even healthy food choices, which can lead to excess calories, weight gain and other health issues. However, measuring serving sizes doesn’t need to be a complicated task. Use these everyday objects as visuals to guide how much food you are putting on your plate and as an easy way to keep your serving sizes (and waistline!) in check. Serving Size Visual 1 cup of fruits (1 medium fruit) or vegetables or Baseball, tennis ball, yo-yo, 1 fist, or ice cream whole grains scoop ½ cup 2 golf balls, 7 cotton balls, ½ baseball, light bulb, or a billiard ball 3 ounces of beef, poultry or fish A dollar bill, a deck of cards, checkbook, an iPod, mini pack of tissues, audio cassette tape, box of 8 crayons, 2-3 CDs (for sliced meat), or outstretched palm 1 ounce of meat ½ cup cooked beans, 1 egg, 2 tablespoons of peanut butter, base of tea cup 1 pancake CD/DVD 1 baked potato Computer mouse or 1 medium fist 1 piece of bread 1 cassette tape or index card 1 piece of cornbread or a roll 1 bar of soap 2 tablespoons of peanut butter Ping pong ball 1 teaspoon of olive oil Standard postage stamp 1 teaspoon of margarine 1 dice or finger tip 1 ounce of cheese 3 dice 1 ½ ounce of hard cheese 4 dice, 3 dominos, 9 volt battery, or index and middle finger 1 ounce of nuts 1 handful or 1 golf ball 1 ounce of chips or pretzels 2 handfuls For more information on heart-healthy eating visit www.Heart.org/Nutrition or contact the American Heart Association at [email protected] or (800) 242-8721. -

Portion Distortion Written by Joseph Ewing, RD, LDN

Portion Distortion Written by Joseph Ewing, RD, LDN Over the past several years, portion sizes have increased significantly! With this increase in portion sizes, there has been a noticeable increase in obesity in people of all ages and ethnicities. Portion distortion refers to what “we” feel is a “normal” portion size versus what is actually being served. For example, a standard portion of steak is 3 ounces… Have you ever gone to a restaurant and ordered a 3 ounce steak? No, because it is not available. Most times when order a steak they come in 8 ounces, 12 ounces, 24 ounces or more! That’s incredible! We’re talking about an astronomical calorie difference. The recommended 3oz Filet Mignon has 130 calories vs. an 8 ounce filet mignon with 301 calories (served at Outback Steakhouse (www.caloriecount.com)). Portion vs. Serving Image: milesforthought.wordpress.com According to the National Institutes of Health, a “portion” is how much food you choose to eat at one time, whether it is at home, in a restaurant, prepackaged or homemade. A “serving” size is a specific amount of food or beverage such as 1 cup of pudding or 1 slice of bread. Sometimes when you are eating a “portion” of food, it matches the serving size, but many times it does not. In order to explain this concept, let’s look at a can of Campbell’s Condensed Tomato Soup. Serving size is ½ cup Servings per container are about 2.5. This means if you eat this whole can of soup you would be consuming 2.5 servings of soup! If you consumed 1 (1/2 cup) portion of this soup, you would consume 480mg of If you consumed the sodium. -

Meeting the NSLP New Meal Pattern

We Can Do This: Advice and Resources for Meeting the NSLP New Meal Pattern as of December 2012 Purpose: School Nutrition Professionals are in the process of implementing the new USDA Meal Pattern and have asked for SNA to provide easy- to-find answers to their Meal Pattern questions as well as sample menus and tools from States and local school districts that will help others not have to “reinvent the wheel.” For the entire “We Can Do This: Advice and Resources for Meeting NSLP New Meal Pattern,” visit www.schoolnutrition.org/mealpattern. Contents: This Resource Guide will be updated as new guidance and additional examples become available. USDA Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ’s) are incorporated in the appropriate chapter(s). This Guide covers Lunch Programs only. Ad Hoc Committee: Colleen Fillmore, SNS Pat McCoy, SNS U.S. Department of Agriculture Director of Child Nutrition Vice President, Field Sales Washington, DC/Alexandria, VA Idaho Department of Education Schwan’s Food Service, Inc. Boise, ID Marshall, MN Project Consultant: Wanda Grant, SNS Katie Millett George Sneller (retired) Child Nutrition Director Director Jacksonville, FL Palm Springs Unified School District MA Department of Elementary and Secondary Former Child Nutrition Director Palm Springs, CA Education Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Abington, MA Washington State Catherine Digilio Grimes, SNS State Director, School Nutrition Programs Jean Ronnei, SNS SNA Staff: Virginia Department of Education Director, Nutrition & Custodial Services Cathy Schuchart -

Freezing Convenience Foods Include: • You Prepare Food When You Have Time

FreezingFreezing convenienceconvenience foodsfoods that you’ve prepared at home PNW 296 By C. Raab and N. Oehler our freezer can help you prepare for busy days • You can save money by making convenience foods ahead, parties, or unexpected company. By yourself. planning a steady flow of main dishes, baked Y On the other hand: goods, desserts, and other foods, you can make good • Freezing is expensive when you total the cost of use of your freezer and your time. packaging, energy use, and the freezer itself. Benefits of freezing convenience foods include: • You prepare food when you have time. • You use more energy to cook, freeze, and reheat a dish than you would use to cook it for immediate • You use your oven more efficiently by baking more consumption. than one dish at a time. • Prepared foods have a relatively short storage life • You avoid waste by freezing leftovers to use as compared to the storage life of their ingredients “planned overs.” (such as frozen fruits, vegetables, and meat). • You can prepare special diet foods and baby foods in • Unless you have a microwave, you must allow quantity and freeze them in single portions. plenty of time for thawing. • You save time by doubling or tripling recipes and • Some products don’t freeze well. Others don’t justify freezing the extra food. the labor and expense of freezing. • If you normally cook for just one or two, you can freeze individual portions of an ordinary recipe for later use. A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication Oregon State University • Washington State University • University of Idaho Contents • Use moisture-vapor-resistant packaging such as plas- Preparing foods for freezing .......................................2 tic containers, freezer bags, heavy-duty aluminum Freezer storage ............................................................2 foil, and coated freezer paper to preserve the quality From the freezer to the table .......................................3 of frozen food. -

Food Portions and Serving Sizes in Diabetes Meal Plans

Food Portions and Serving Sizes in Diabetes Meal Plans This slide show explains: • Difference between a serving and a portion • Where to find serving sizes on food labels • Serving sizes for meats, fruits, vegetables • Using your hand to estimate portions Pia has a Bachelors Degree in Clinical Nutrition from Cornell University and a Masters of Science in Nutrition from New York University. She completed a dietetic internship at the Bronx Veterans Medical Center in order to become a registered dietitian. Prior to joining BD, Pia educated people with diabetes about medical nutrition therapy in a private physicians office, an outpatient clinic at a hospital and a nursing home where she counseled patients one-on-one and in group classes. Next slide The difference between a serving size and a portion of food A "serving size" is the amount of food that is used to calculate the nutritional values on a food label. For example, a serving size might be 1 cookie, or ½ cup of cereal. A "portion" is the actual amount of a food that you choose to eat. A portion might consist of several “servings”. Example 1 Example 2 A serving of unsweetened applesauce is ½ cup, Your diabetes meal plan may say that you should eat and it has 14 grams of carbohydrate. 3 fruit servings per day. You like bananas, but a serving of banana is either ½ of a large banana or However, you may choose to eat a 1 cup portion one small banana (less than 6 inches long). of applesauce. That equals 2 servings of applesauce, totaling 28 grams of carbohydrate. -

Predicting Real-Life Eating Behaviours Using Single School Lunches in Adolescents

nutrients Article Predicting Real-Life Eating Behaviours Using Single School Lunches in Adolescents Billy Langlet 1,* , Petter Fagerberg 1 , Anastasios Delopoulos 2 , Vasileios Papapanagiotou 2, Christos Diou 2 , Christos Maramis 3 , Nikolaos Maglaveras 3, Anna Anvret 4 and Ioannis Ioakimidis 1 1 Innovative Use of Mobile Phones to Promote Physical Activity and Nutrition across the Lifespan (the IMPACT) Research Group, Department of Biosciences and Nutrition, Karolinska Institutet, 14152 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] (P.F.); [email protected] (I.I.) 2 Multimedia Understanding Group, School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] (A.D.); [email protected] (V.P.); [email protected] (C.D.) 3 Laboratory of Medical Informatics, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54636 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (N.M.) 4 Mandometer Clinics, 14104 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +00462033996 Received: 30 January 2019; Accepted: 13 March 2019; Published: 20 March 2019 Abstract: Large portion sizes and a high eating rate are associated with high energy intake and obesity. Most individuals maintain their food intake weight (g) and eating rate (g/min) rank in relation to their peers, despite food and environmental manipulations. Single meal measures may enable identification of “large portion eaters” and “fast eaters,” finding individuals at risk of developing obesity. The aim of this study was to predict real-life food intake weight and eating rate based on one school lunch. Twenty-four high-school students with a mean (±SD) age of 16.8 yr (±0.7) and body mass index of 21.9 (±4.1) were recruited, using no exclusion criteria. -

Appendix B -1 B Appendix

B Appendix Using Column 6 of the Food Buying Guide Yield Tables Column 6 of the Food Buying Guide (FBG) Yield Tables provide information to help you plan menus, make purchasing decisions, and ensure prepared meals meet Child Nutrition Programs meal pattern requirements. Below are practical ways the information in Column 6 can be utilized. A. Determine the amount of food to purchase. Column 6 provides the quantity of ready-to-cook or cooked food provided in the “As Purchased” (AP) form of the food. This information is used to calculate the amount of food the Child Nutrition Program operator needs to purchase and/or prepare based on specifc yield information. See the examples below: EXAMPLE: A recipe contains 2 pounds of fresh, diced watermelon. Use the information in Column 6 to determine the amount of fresh, whole watermelon to purchase, as follows: Section 3 - Fruits 1. Food As 2. Purchase 3. Servings 4. Serving Size 5. Purchase 6. Additional Information Purchased, AP Unit per per Meal Units for Purchase Contribution 100 Unit, EP Servings WATERMELON Watermelon, fresh3 Pound 6.10 1/4 cup diced fruit 16.40 1 lb AP= 0.61 lb (about 1-1/2 Whole without rind cups) ready-to-serve raw, 1/2- inch diced watermelon without rind The information in Column 6 indicates 1 lb of whole, fresh watermelon as purchased yields 0.61 lb ready-to-serve, raw, 1/2 inch pieces, diced, without rind. Divide 2 lb by 0.61 lb 2 0.61 = 3.28 lb To ensure enough food is purchased, round up to 3.5 lb. -

Convenience Foods Comparisons

CONVENIENCE FOODS COMPARISONS TOPICS IN ADVANCE • Comparing food labels 1. If possible, choose a label set that relates to recipe being used that day • Identifying healthy or in a previous class options when eating out DURING CLASS • Comparing Unit Price 1. ASK: What information on the food label do you use now? How do you ESTIMATED TIME use it? 10 minutes 2. Pass around convenience labels. Explain that there is a mix of packaged, frozen, and restaurant versions of the same food item as well MATERIALS • Nutrition labels for as the Cooking Matters recipe restaurant, store- 3. ASK: When comparing this food item, what nutrients may you want to bought, and homemade versions of: pay particular attention to? Review “Reading Food Labels” • Pizza 4. Have participants share the percent daily values or grams/milligrams for • French Fries the relevant nutrients (for example: fat, sugar, salt, or fiber) • Chicken • Mac & Cheese 5. Consider filling out a chart to help participants compare and review the • Tacos different options. Example for pizzas: Cooking Take-out VARIATIONS Take-out Matters Frozen Thin Crust Pizza Three Cheese • During the third lesson, The Works Cheese Pizza Margherita Pizza ask participants why Pizza Pizza they might choose the Serving Size 190g 133g 128g 85g convenience item over (1 slice) homemade, and how Saturated Fat 3g 3.5g 5.5g 4g they could make it healthier when they do. Sugar 5g 4g 3g 6g • Convenience food labels may also be Fiber 3g 2g 2g 2g used in the “Line Them Cost per Up” Activity $1.41 $0.67 $1.54 $2.25 Serving • Compare unit pricing to discuss the cost benefits of making food at home 6. -

Menu Generator & Drop Table

Menu Generator & Drop Table Sample file Suitable for use with any Fantasy RPG Introduction: While my original intention was just to put out a “quick” drop table for generating decent enough menus that your players might encounter at a local establishment, it occurred to me that what one GM might find useful, the next would find abhorrently complex and the next not nearly complex enough. I like the idea of giving GM useful tools that can flex to meet their needs. To this end the drop table is a bit multi-purpose and if you would rather not print the table, a series of printer-friendly tables are included as part of this product. I’ve also added some blank space at the end of each table so you can feel free to add your own entries. If your players are adventuring in an area with a certain set of specialties, why wouldn’t the local menus reflect this? When possible I tried to use more modern equivalents for certain items, but there is a richness in the old names for some dishes I couldn’t mess with. So things make sense I’ve also included a small list of definitions to help you explain the food to your players. In case you happen to be interested, some of these dishes can be made in the modern era. If you want to try this I can recommend three sites for medieval recipes: The Gode Cookery, Medieval Cookery, and Celtnet. Sample file -Christopher Stogdill AKA the Frugal GM Directions for Use: Drop Table: Either roll a 1d20 to indicate a pre-made menu, or roll five different-sized dice.