How Circus Training Can Enhance the Well-Being of Autistic Children and Their Families

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspiring Mathematical Creativity Through Juggling

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 10 | Issue 2 July 2020 Inspiring Mathematical Creativity through Juggling Ceire Monahan Montclair State University Mika Munakata Montclair State University Ashwin Vaidya Montclair State University Sean Gandini Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Monahan, C. Munakata, M. Vaidya, A. and Gandini, S. "Inspiring Mathematical Creativity through Juggling," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 10 Issue 2 (July 2020), pages 291-314. DOI: 10.5642/ jhummath.202002.14 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol10/iss2/14 ©2020 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. Inspiring Mathematical Creativity Through Juggling Ceire Monahan Department of Mathematical Sciences, Montclair State University, New Jersey, USA -

Happy Birthday!

THE THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2021 Quote of the Day “That’s what I love about dance. It makes you happy, fully happy.” Although quite popular since the ~ Debbie Reynolds 19th century, the day is not a public holiday in any country (no kidding). Happy Birthday! 1998 – Burger King published a full-page advertisement in USA Debbie Reynolds (1932–2016) was Today introducing the “Left-Handed a mega-talented American actress, Whopper.” All the condiments singer, and dancer. The acclaimed were rotated 180 degrees for the entertainer was first noticed at a benefit of left-handed customers. beauty pageant in 1948. Reynolds Thousands of customers requested was soon making movies and the burger. earned a nomination for a Golden Globe Award for Most Promising 2005 – A zoo in Tokyo announced Newcomer. She became a major force that it had discovered a remarkable in Hollywood musicals, including new species: a giant penguin called Singin’ In the Rain, Bundle of Joy, the Tonosama (Lord) penguin. With and The Unsinkable Molly Brown. much fanfare, the bird was revealed In 1969, The Debbie Reynolds Show to the public. As the cameras rolled, debuted on TV. The the other penguins lifted their beaks iconic star continued and gazed up at the purported Lord, to perform in film, but then walked away disinterested theater, and TV well when he took off his penguin mask into her 80s. Her and revealed himself to be the daughter was actress zoo director. Carrie Fisher. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) HURSDAY PRIL T , A 1, 2021 Today is April Fools’ Day, also known as April fish day in some parts of Europe. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Flips and Juggles A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Flips and Juggles ADissertationsubmittedinpartialsatisfactionofthe requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics by Jay Cummings Committee in charge: Professor Ron Graham, Chair Professor Jacques Verstra¨ete, Co-Chair Professor Fan Chung Professor Shachar Lovett Professor Je↵Remmel Professor Alexander Vardy 2016 Copyright Jay Cummings, 2016 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Jay Cummings is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on micro- film and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION To mom and dad. iv EPIGRAPH We’ve taught you that the Earth is round, That red and white make pink. But something else, that matters more – We’ve taught you how to think. — Dr. Seuss v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Epigraph ...................................... v TableofContents.................................. vi ListofFigures ................................... viii List of Tables . ix Acknowledgements ................................. x AbstractoftheDissertation . xii Chapter1 JugglingCards ........................... 1 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.1.1 Jugglingcardsequences . 3 1.2 Throwingoneballatatime . 6 1.2.1 The unrestricted case . 7 1.2.2 Throwingeachballatleastonce . 9 1.3 Throwing m 2ballsatatime. 16 1.3.1 A digraph≥ approach . 17 1.3.2 Adi↵erentialequationsapproach . 21 1.4 Throwing di↵erent numbers of balls at di↵erent times . 23 1.4.1 Boson normal ordering . 24 1.5 Preserving ordering while throwing . 27 1.6 Juggling card sequences with minimal crossings . 32 1.6.1 A reduction bijection with Dyck Paths . 36 1.6.2 A parenthesization bijection with Dyck Paths . 48 1.6.3 Non-crossingpartitions . 52 1.6.4 Counting using generating functions . -

2009–2010 Season Sponsors

2009–2010 Season Sponsors The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2009–2010 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. Benefactor Audrey and Rick Rodriguez Yvonne Cattell Renee Fallaha $50,001-$100,000 Marilynn and Art Segal Rodolfo Chacon Heather M. Ferber José Iturbi Foundation Kirsten and Craig M. Springer, Joann and George Chambers Steven Fischer Ph.D. Rodolfo Chavez The Fish Company Masaye Stafford Patron Liming Chen Elizabeth and Terry Fiskin Charles Wong $20,001-$50,000 Wanda Chen Louise Fleming and Tak Fujisaki Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Margie and Ned Cherry Jesus Fojo The Capital Group Companies Friend Drs. Frances and Philip Chinn Anne Forman Charitable Foundation $1-$1,000 Patricia Christie Dr. Susan Fox and Frank Frimodig Richard Christy National Endowment for the Arts Maureen Ahler Sharon Frank Crista Qi and Vincent Chung Eleanor and David St. -

Analysis and Visualization of Collective Motion in Football Analysis of Youth Football Using GPS and Visualization of Professional Football

UPTEC F 15068 Examensarbete 30 hp December 2015 Analysis and visualization of collective motion in football Analysis of youth football using GPS and visualization of professional football Emil Rosén Abstract Analysis and visualization of collective motion in football Emil Rosén Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten Football is one of the biggest sports in the world. Professional teams track their player's positions using GPS (Global Positioning System). This report is divided into Besöksadress: two parts, both focusing on applying collective motion to football. Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 Hus 4, Plan 0 The goal of the first part was to both see if a set of cheaper GPS units could be used to analyze the collective motion of a youth football team. 15 football players did two Postadress: experiments and played three versus three football matches against each other while Box 536 751 21 Uppsala wearing a GPS. The first experiment measured the player's ability to control the ball while the second experiment measured how well they were able to move together as Telefon: a team. Different measurements were measured from the match and Spearman 018 – 471 30 03 correlations were calculated between measurements from the experiments and Telefax: matches. Players which had good ball control also scored more goals in the match and 018 – 471 30 00 received more passes. However, they also took the middle position in the field which naturally is a position which receives more passes. Players which were correlated Hemsida: during the team experiment were also correlated with team-members in the match. http://www.teknat.uu.se/student But, this correlation was weak and the experiment should be done again with more players. -

Save the Dates! Re-Enrollment Deadline - FRIDAY

Richmond Waldorf School Newsletter Wednesday, February 12, 2014 In This Issue Save the Dates! Re-Enrollment Deadline - FRIDAY Important Financial News ___________________________ Inclement Weather Policy February 12 Extended Friday Gathering Observation Day Circus Zirkus - Part I and II 8:30 - 10:00 am Help Support the Circus! & PA Meeting Summary Wednesday Morning Parent Gathering (next to Eurythmy Room) Waldorf Guys' Night Out 8:30- 10:00 am Mason Hopkins - Artwork & Relay Foods @ RWS Basketball Game Lost and Found RWS v. Good Shepherd High School Admissions Info 4:00- 5:00 pm 1415 Grayland Avenue Richmond, VA 23220 Quick Links February 13 Waldorf Guys' Night Out 6:00 - 9:00 pm Knaup Residence 2721 East Weyburn Road Richmond, VA 23235 February 14 Noon Dismissal for all students RWS Online Calendar (After Care - regular hours) February 2014 - AWSNA Inform February 17-21 Newsletter Mid-Winter Break NO CLASSES Cars4Causes and RWS February 22 Basketball Game RWS v. St. Michael's 12:45 - 1:45 pm Singleton Campus 10510 Hobby Hill Rd Richmond, VA 23235 February 26 Wednesday Morning Parent Gathering (next to Eurythmy Room) 8:30- 10:00 am & RWS Board Meeting (in Westover Baptist Library) 5:30 - 7:00 pm Re-enrollment Deadline This Friday February 14! Don't forget to return your enrollment contract to the RWS office no later than THIS FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 14 BY 5:00 PM to avoid the $250 late fee! Extra copies of the contracts and tuition & fee schedules are available in the front hallway upstairs. Look next to the bulletin board in the wall pockets if you need one. -

View, MN Wild Iron Images, St

#32 Eileen Binkley #66 Rhonda Sebert #93 Kathleen Withers ARTISTS Eileen Binkley Art Rhonda Lynn Studio Kaity Klothes Mixed Media Painting Clothing #32 Amber Johnson #67 Randy Birocci #94 Kari Surprenant Pink Indicates Artists New to the A Johnson Art Birocci's Woodworking KS Custom Creations Brookings Summer Arts Festival Mixed Media Wood Wood BOOTH #33 Laura Jewell #68 Dennis and Twyla McElree #95 Darla Ellickson Laura Jewell Artwork Echo Valley Metalworks Ellickson Jewelry Collection #1 Charlene Norvil and Diane Doren Painting Metal Jewelry Norenwood #34 Darlene Gustafson #69 John Cartwright #96 Rebecca Schnackenberg Wood Darlene's Ceramics & Crafts John Cartwright Railroad Art Dos Gatos Designs #2 Steve Coburn Painting Graphics Metal Steve Coburn Pottery #35 Annette Moore #70 Bruce Jessen #97 Bob Holloway Pottery/Ceramic Ms. Annette & Dave’s Antique Ceiling Tins Dust and Noise Woodworking Bob Holloway Studio & Gallery #3 George H. Jones Mixed Media Wood Mixed Media Fine Art By George Jones #36 Robert and Lana Hendricks #71 Shelleen Weeks #98 Kathy Besthorn Painting Silverfish 'N' Things Do-OverS! A Light Goes On, Inc. #4 Stacy Kleymann Metal Jewelry Photography GimStonz #37 Kathy Kirchoff #72 Judith Edenstrom and #99 Mike Eilers Jewelry Recollections Collette Gesinger Born in a Barn #5 Dennis Beecroft Mixed Media Artifacts Wood JDS Gems...and More #38 Randy and Jody Feucht Mixed Media #100 Mary Ann Bergeron Leather Creative Signs N More #73 Roger Erickson Affordable Designs by Mary Ann #5 Sharon Beecroft Wood Lake Shore Creations Jewelry JDS Gems...and More #39 Chaeli Kohn Wood #101 Becky Covert Photography Shady Grove Pottery #74 Dan and Janna Kuklis Dakota Macramé #6 Elizabeth Zokaites Pottery/Ceramic Woodworks by Dan Textiles/Fibers E.A. -

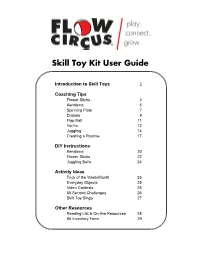

Skill Toy Kit User Guide

Skill Toy Kit User Guide Introduction to Skill Toys 2 Coaching Tips Flower Sticks 3 Kendama 5 Spinning Plate 7 Diabolo 9 Flop Ball 11 Yo-Yo 12 Juggling 14 Creating a Routine 17 DIY Instructions Kendama 20 Flower Sticks 22 Juggling Balls 24 Activity Ideas Trick of the Week/Month 25 Everyday Objects 25 Video Contests 25 60 Second Challenges 26 Skill Toy Bingo 27 Other Resources Reading List & On-line Resources 28 Kit Inventory Form 29 Introduction to Skill Toys You and your team are about to embark on a fun adventure into the world of skill toys. Each toy included in this kit has its own story, design, and body of tricks. Most of them have a lower barrier to entry than juggling, and the following lessons of good posture, mindfulness, problem solving, and goal setting apply to all. Before getting started with any of the skill toys, it is important to remember to relax. Stand with legs shoulder width apart, bend your knees, and take deep breaths. Many of them require you to absorb energy. We have found that the more stressed a player is, the more likely he/she will be to struggle. Not surprisingly, adults tend to have this problem more than kids. If you have players getting frustrated, remind them to relax. Playing should be fun! Also, remind yourself and other players that even the drops or mess-ups can give us valuable information. If they observe what is happening when they attempt to use the skill toys, they can use this information to problem solve. -

Martial Power™

Martial Power™ ROLEPLAYING GAME SUPPLEMENT Rob Heinsoo • David Noonan • Chris Sims • Robert J. Schwalb Martial Power_Ch0.indd 1 9/4/08 2:04:33 PM CREDITS Design Cover Illustration Rob Heinsoo (lead), William O’Connor David Noonan, Chris Sims, Robert J. Schwalb Graphic Designer Additional Design Emi Tanji Andy Collins, Nicolas Logue, Rodney Thompson Interior Illustrations Development Steve Belledin, Leonardo Borazio, Steve Ellis, Stephen Radney-MacFarland (lead), Wayne England, Jason A. Engle, Gonzalo Flores, Stephen Schubert, Peter Schaefer Adam Gillespie, Brian Hagan, Jeremy Jarvis, Ron Lemen, Wes Louie, Howard Lyon, Lee Moyer, Lucio Parrillo, Editing Jim Pavelec, Steve Prescott, Vincent Proce, Ron Spears, Jeremy Crawford (lead), Ron Spencer, Stephen Tappin, Mark Tedin, Beth Trott, M. Alexander Jurkat, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel Ben Wootten Managing Editing Publishing Production Specialist Kim Mohan Erin Dorries Director of R&D, Roleplaying Games/Book Publishing Prepress Manager Bill Slavicsek Jefferson Dunlap D&D Story Design and Development Manager Imaging Technician Christopher Perkins Sven Bolen D&D System Design and Development Manager Production Manager Andy Collins Cynda Callaway Art Director Game rules based on the original DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® Ryan Sansaver rules created by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, and the later editions by David “Zeb” Cook (2nd Edition); Jonathan Special thanks to Brandon Daggerhart, keeper of Shadowfell Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams, Richard Baker, and Peter Adkison (3rd Edition); and Rob Heinsoo, Andy Collins, and James Wyatt (4th Edition). 620-21789720-001 EN U.S., CANADA, ASIA, PACIFIC, EUROPEAN HEADQUARTERS WIZARDS OF THE COAST, BELGIUM 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 & LATIN AMERICA Hasbro UK Ltd ’t Hofveld 6D First Printing: October 2008 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. -

Qt4vn913nb.Pdf

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Flips and Juggles Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4vn913nb Author Cummings, Jonathan James Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Flips and Juggles A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics by Jay Cummings Committee in charge: Professor Ron Graham, Chair Professor Jacques Verstra¨ete,Co-Chair Professor Fan Chung Graham Professor Shachar Lovett Professor Jeff Remmel Professor Alexander Vardy 2016 Copyright Jay Cummings, 2016 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Jay Cummings is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on micro- film and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION To mom and dad. iv EPIGRAPH We've taught you that the Earth is round, That red and white make pink. But something else, that matters more { We've taught you how to think. | Dr. Seuss v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Epigraph . .v Table of Contents . vi List of Figures . viii List of Tables . ix Acknowledgements . .x Vita......................................... xii Abstract of the Dissertation . xiii Chapter 1 Juggling Cards . .1 1.1 Introduction . .1 1.1.1 Juggling card sequences . .3 1.2 Throwing one ball at a time . .6 1.2.1 The unrestricted case . .7 1.2.2 Throwing each ball at least once . .9 1.3 Throwing m ≥ 2 balls at a time . 16 1.3.1 A digraph approach . -

Wildfire: a Warm Welcome Home

Wildfire: A Warm Welcome Home For all the places I have traveled and the communities I have been a part of, many have come close, but none equal that of the family of Wildfire. I was a stranger in a strange world for only mere minutes. This retreat into the woods of Connecticut brings together the flow arts community of fire-breathers, fire- spinners, jugglers and other live performers from across the country to teach and learn from one another. Even more importantly, it’s a place for open-minded individuals of all ages and backgrounds to support and push each other through life. I don’t spin any fire and can barely hold my pen without dropping it. That didn’t matter to one of my best friends, Dani Rei, who has been attending this event for the past seven seasons (there are two to three retreats a year for this event). She gave me a green contact juggling ball to practice with and eventually gave me my own red one. She encouraged me to come along and experience something fresh and positive. Positive it was! One of the first people I met was a long-time attendee named Patrick. He greeted me and when he learned it was my first time, he gave me a big hug and said, “Welcome home.” Even Dani Rei had a similar experience her first time. “I was so nervous at how they would react to me. I’ve only been spinning for about year,” she said. “I remember everyone telling me, ‘Welcome home.’ Most of them were excited for me, encouraged me and offered to teach me a trick right on the spot.” Everyone camps out in tents at J.N. -

Juggling Festival July 17-23, 2006

The International Jugglers’ Association announces its 59th Annual Juggling Festival July 17-23, 2006 Oregon Convention Center, Portland, OR Register online at www.juggle.org/festival Seven days of open juggling, workshops, shows, competitions, parties, vendors, laughter, music and more...surrounded by some of the most beautiful country on the West Coast. Catch you there! the air behind him. I sat stunned as I watched 2006 GUEST ARTISTS Jérôme catch every single sheet of erratically flying paper before they hit the ground. The memory of Jérôme’s phenomenal display of superhuman reflexes stays with me to this day. If you would like to expand your awareness of juggling and performing, you owe it to yourself to attend Jérôme Thomas’ workshop.” Based in Paris, Jérôme has a long history of work in circus and cabaret, followed by a concentrated study of the intersection between Based in Olympia, WA, the Mud Bay Jugglers improvisational artistic juggling and jazz music. (Doug Martin, Alan Fitzthum and Harry Levine) In 1993, he founded ARMO (Association for recently celebrated their 25th anniversary and Research in the Manipulation of Objects)/Jérôme were featured in the Jan./Feb. issue of JUGGLE Thomas Company, producing many critically magazine. Doug’s son, Amiel, is a third of the acclaimed shows and popular workshops. He has Juggling Jollies, who will also be on hand (River taught at the Moscow Circus School. and Jules round out the trio). The Mud Bay Jérôme will lead a limited number of class Jugglers will be available during the festival for participants in an intense workshop focusing several free workshops on music, choreography on creativity and development, culminating in and their innovative technique, not to mention a performance to be featured at the festival’s autographs, long philosophical conversations, Cascade of Stars show.