Exploring Students' Knowledge of And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISTRICTS Peter Calamari Asst

DISTRICTS Peter Calamari Asst. Vice President Facilities Operations and Development 614.292.3377 Facilities Operations Functional Org Chart Administration Remi Timmons June 22, 2021 Office Admin. Associate 614.247.4094 Zone 1 Buildings 18th Avenue Library, 209 W. 18th, Baker Systems, Bricker Hall, Caldwell Laboratory, Central Service Building, Cockins Hall, Denney Hall, Derby Zone 1 Hall, Dreese Laboratories, Dulles Hall, Enarson Classroom, French Field House, Hayes Hall, Hopkins Hall, Ice Rink, Independence Hall, Jesse Karen Crabbe Owens North, Journalism Building, Maintenance Building, Math Building, Math Tower, McCorkle Aquatic Pavilion, McCracken Power Plant, Zone Leader Northwood-High Building, Ohio Stadium, Physical Activity & Education Services, Recreation & Physical Activity Center, St. John Arena, Stillman 614.688.8264 Hall, University Hall, Wilce Student Health Center, Women’s Field House Academic District 3,513,341 Sq Ft (Services All Campus) Zone 2 Buildings Kenny King 140 W. 19th, Arps Hall, Bolz Hall, Celeste Laboratory, Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering, Chemical Engineering Storage, Converse Hall, Evans Zone 2 Laboratory, Fisher Hall, Fontana Laboratories, Gerlach Hall, Hitchcock Hall, Hughes Hall, Knowlton Hall, Koffolt Laboratories, MacQuigg Laboratory, Leader Jim Wright Mason Hall, McPherson Chemical Laboratory, Mershon Auditorium, Newman & Wolfrom Laboratory, Page Hall, Pfahl Hall, Physics Research 614.688.8632 Zone Leader (Interim) Building, Ramseyer Hall, Smith Laboratory, Schoenbaum Hall, Scott Laboratory, Student Academic Service Building, Sullivant Hall, Tuttle Park 614.292.9844 Place Garage Retail Space, Watts Hall, Weigel Hall, Wexner Center for the Arts 3,694,839 Sq Ft Administration Zone 3 Buildings Kathy Snoke Atwell Hall, BRT, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Davis Heart & Lung Research Institute, Evans Hall, Graves Hall, Hamilton Hall, Meiling Hall, Office Admin. -

NN Aug 2013.Indd

NOUVELLES THE O HIO S TATE U NIVERSITY AUGUST 2013 AND D IRECTORY NOUVELLES CENTER FOR M EDIEVAL & R ENAISSANCE S TUDIES CALENDAR AUTUMN 2013 30 AugustA t 2013 15 October 2013 CMRS Lecture Series CMRS Film Series: The Conquerer Worm (1968) Christina Normore, Northwestern University Directed by Michael Reeves Between the Dishes and What Courtiers Found There Starring: Vincent Price, Ian Ogilvy, and Rupert Davies 3:00 PM, 090 18th Avenue Library 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall 26 October 2013 Ohio Medieval Colloquium Heidelberg University 3 September 2013 Tiffi n, OH CMRS Film Series: Kirikou and the Sorceress (1998) Directed by Michael Ocelot 29 October 2013 Starring: Doudou Gueye Thiaw, Miamouna N’Diaye CMRS Film Series: The Wicker Man (1973) and Awa Sene Directed by Robin Hardy 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall Starring: Edward Woodward, Christopher Lee, and Diane Cilento 17 September 2013 7:30 PM,M, 455B Hagerty ge y Hall CMRS Film Series: Spirited Away (2001) Directed by Hayao Miyazaki Starring: Daveigh Chase, Suzanne Pleshette, and Susan Egan 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall 8 November 2013 27 September 2013 CMRS Lecture Series: MRGSA Lecture CMRS Lecture Series: Francis Lee Utley Lecture Co-Sponsored by the Medieval and Renaissance Graduate Co-Sponsored by the Center for Folklore Studies Student Association Luisa Del Giudice, UCLA Christopher Dyer, University of Leicester Mountains of Cheese, Rivers of Wine: Paesi di Cuccagna Diets of the Poor in Medieval England and Other Gastronomic Utopias 3:00 PM, 090 18th Avenue Library 3:00 PM, 090 18th Avenue -

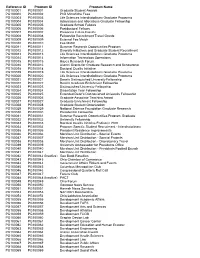

Program FDM Values

Reference ID Program ID Program Name PG100001 PG100001 Graduate Student Awards PG100002 PG100002 PhD Microfiche Fees PG100003 PG100003 Life Sciences Interdisciplinary Graduate Programs PG100004 PG100004 Admissions and Allocations Graduate Fellowship PG100005 PG100005 Graduate School Fellows PG100006 PG100006 Postdoctoral Fellows PG100007 PG100007 Preparing Future Faculty PG100008 PG100008 Fellowship Recruitment Travel Grants PG100009 PG100009 External Fee Match PG100010 PG100010 Fee Match PG100011 PG100011 Summer Research Opportunities Program PG100012 PG100012 Diversity Initiatives and Graduate Student Recruitment PG100013 PG100013 Life Sciences Interdisciplinary Graduate Programs PG100014 PG100014 Information Technology Operations PG100015 PG100015 Hayes Research Forum PG100016 PG100016 Alumni Grants for Graduate Research and Scholarship PG100018 PG100018 Doctoral Quality Initiative PG100019 PG100019 Life Sciences Interdisciplinary Graduate Programs PG100020 PG100020 Life Sciences Interdisciplinary Graduate Programs PG100021 PG100021 Dean's Distinguished University Fellowship PG100022 PG100022 Dean's Graduate Enrichment Fellowship PG100023 PG100023 Distinguished University Fellowship PG100024 PG100024 Dissertation Year Fellowship PG100025 PG100025 Extended Dean's Distinguished University Fellowship PG100026 PG100026 Graduate Associate Teaching Award PG100027 PG100027 Graduate Enrichment Fellowship PG100028 PG100028 Graduate Student Organization PG100029 PG100029 National Science Foundation Graduate Research PG100030 PG100030 Presidential -

Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance

INAUGURAL CONFERENCE Transmissions and Traces: Rendering Dance Oct. 19-22, 2017 HOSTED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF DANCE Sel Fou! (2016) by Bebe Miller i MAKE YOUR MOVE GET YOUR MFA IN DANCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN We encourage deep engagement through the transformative experiences of dancing and dance making. Hone your creative voice and benefit from an extraordinary breadth of resources at a leading research university. Two-year MFA includes full tuition coverage, health insurance, and stipend. smtd.umich.edu/dance CORD program 2017.indd 1 ii 7/27/17 1:33 PM DEPARTMENT OF DANCE dance.osu.edu | (614) 292-7977 | NASD Accredited Congratulations CORD+SDHS on the merger into DSA PhD in Dance Studies MFA in Dance Emerging scholars motivated to Dance artists eager to commit to a study critical theory, history, and rigorous three-year program literature in dance THINKING BODIES / AGILE MINDS PhD, MFA, BFA, Minor Faculty Movement Practice, Performance, Improvisation Susan Hadley, Chair • Harmony Bench • Ann Sofie Choreography, Dance Film, Creative Technologies Clemmensen • Dave Covey • Melanye White Dixon Pedagogy, Movement Analysis Karen Eliot • Hannah Kosstrin • Crystal Michelle History, Theory, Literature Perkins • Susan Van Pelt Petry • Daniel Roberts Music, Production, Lighting Mitchell Rose • Eddie Taketa • Valarie Williams Norah Zuniga Shaw Application Deadline: November 15, 2017 iii DANCE STUDIES ASSOCIATION Thank You Dance Studies Association (DSA) We thank Hughes, Hubbard & Reed LLP would like to thank Volunteer for the professional and generous legal Lawyers for the Arts (NY) for the support they contributed to the merger of important services they provide to the Congress on Research in Dance and the artists and arts organizations. -

SEPTEMBER 2015 CALENDAR Autumn 2015

NOUVELLES NOUVELLES SEPTEMBER 2015 CALENDAR AUTUMN 2015 30-31 October Texts and Contexts 2 September Sponsored by the Center for Epigraphical & CMRS Film Series Palaeographical Studies Kirikou and the Sorceress (1998) Virginia Brown Memorial Lecture delivered by Directed by Michel Ocelot Erika Kihlman, University of Stockholm 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall 11 September CMRS Lecture Series Frances Dolan (University of California, Davis) “Compost/Compositions” 4 PM, 18th Avenue Library, Room 090 4 November CMRS Film Series 16 September The Wicker Man (1973) CMRS Film Series Directed by Robin Hardy Spirited Away (2001) 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall Directed by Hayao Miyazaki 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall 5 November CMRS 50th Anniversary Celebration 30 September co-sponsored by MRGSA CMRS Film Series The Name of the Rose (1986) 18 November Directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud CMRS Film Series 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall The Witches of Eastwick (1987) Directed by George Miller 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall 20 November 2 October CMRS Lecture Series: Annual MRGSA Lecture CMRS Lecture Series Jane Hwang Degenhardt (U. Massachusetts Amherst) Andrew Hicks (Cornell University) “The Rise and Fall of Fortune: Commerce and Inter- “Like an Elephant’s Recollection of India: Imperial World History in Doctor Faustus & Friar Philosophies of Audition in Medieval Persian Sufism” Bacon and Friar Bungay” 4 PM, 18th Avenue Library, Room 090 4 PM, 18th Avenue Library, Room 090 8 October CMRS Special Lunchtime Event Ann Blair (Harvard University) “Hidden Hands: Amanuenses and Authorship in Early 4 December Modern Europe” CMRS Lecture Series 12:30 PM, Location TBA Florence Eliza Glaze (Coastal Carolina University) “Bodies, Wounds, and Balance in the History of 21 October Medieval Health and Disease” CMRS Film Series 4 PM, 18th Avenue Library, Room 090 The Conqueror Worm (1968) Directed by Michael Reeves Keep your eyes open in mid-December 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall CMRS Shakespeare Bash Gateway Theatre (Ticketed Event) 23-24 October Details forthcoming.. -

Self-Guided Walking Tour a Self-Guided Walking Tour

visit.osu.edu Self-Guided Walking Tour A self-guided walking tour of the central Columbus campus COVID-19 note: Be aware that some facilities may be closed or Ohio State boasts some of the nation's finest facilities for students, and we encourage have altered hours. Please adhere you to explore them. Join the many students, faculty and staff who crisscross campus to Ohio State's campus visit every day. Please don't enter residence halls or classrooms in session. You can guidelines, found at undergrad. complete this tour in about an hour and a half. Enjoy your visit! osu.edu/visit/guidelines. 1 The Ohio Union is the heart of 4 Mendenhall Laboratory first 8 The Oval, the open grassy area student life, featuring support for more opened in 1905 and is the current stretching from Thompson Library to than 1,000 student organizations, an home of the Department of Geological College Road, has symbolized Ohio instructional kitchen, the Archie M. Griffin Sciences. Check out the "fossil-like" State to students and visitors for Grand Ballroom, meeting rooms and event design of the floor in the main lobby. generations. At the heart of campus, spaces, Sloopy's Diner and other eating This building also houses the Writing the Oval is a favorite place for reading, options, a retail shop, and places to study Center, where the university community relaxing and meeting friends. Legend and relax. Also located at the Ohio Union: gets help with research papers, lab has it that if you take the "Long Walk" the Undergraduate Admissions Welcome reports, dissertations and resumes. -

NN Nov 2013.Indd

NOUVELLES THE O HIO S TATE U NIVERSITY NOVEMBER 2013 NOUVELLES CENTER FOR M EDIEVAL & R ENAISSANCE S TUDIES CALENDAR FALL 2013 8 November 2013 CMRS Lecture Series: Annual MRGSA Lecture Co-Sponsored by the Medieval and Renaissance Graduate Student Association Christopher Dyer, University of Leicester Diets of the Poor in Medieval England 3:00 PM, 090 18th Avenue Library 12 November 2013 CMRS Film Series: The Witches of Eastwick (1987) Directed by George Miller Starring: Jack Nicholson, Cher, and Susan Sarandon 7:30 PM, 455B Hagerty Hall 15-16 November 2013 Texts and Contexts: Center for Epigraphical and Palaeographical Studies Conference Virginia Brown Memorial Lecture Julia Haig Gaisser, Eugenia Chase Guild Professor Emeritus in the Humanities, Bryn Mawr College Excuses, Excuses: Racy Poetry from Catullus to Joannes Secundus 22 November 2013 CMRS Lecture Series Derek Pearsall, Harvard University Feasting and Fun in Langland’s Piers Plowman 3:00 PM, 090 18th Avenue Library 2 December 2013 Holiday Party Hosted by: Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies, Center for the Study of Religion, Center for Folklore Studies, Dversity and Identity Studies Collective at OSU, and American Sign Language Program 4:30-6:30 PM, 455 Hagerty Hall CONTENTS ¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¥ ¤ ¦ ¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¥ ¤ ¦ § ¨ © ¨ © ¨ ! " # $ % $ $ & ' ( ( ) * ¨ ¨ # , - # " / $ + ( ) ) ' . ( 0 ) * © ¨ ¨ ¨ - # 4 , 4 6 § 1 2 ( 3 5 1 . 3 1 ! * ¨ $ # " 6 8 # , " 6 ( 7 0 3 1 2 # 9 $ $ , $ 1 : ; ) 4 4 - $ , $ < = > ? @ A A @ B < = > ? @ A A @ B 1 5 . 7 3 1 : ; 1 2 4 $ % $ 4 , $ " , - $ $ , $ " C " $ $ 9 # # 3 0 7 0 ) ( : 1 3 ) : $ # 4 4 # $ , $ 4 ) 1 ) 2 . : 1 & - 4 # , 4 # 9 # # $ # C C " E D 1 5 . 7 3 1 2 1 ( ) 1 1 3 7 3 1 ) & 5 : ( % # , # , - , , % " 4 4 $ 8 $ # 4 $ E 5 FG G 2 &( . -

Self-Guided Walking Tour a Self-Guided Walking Tour of the Central Columbus Campus

visit.osu.edu Self-Guided Walking Tour A Self-Guided Walking Tour of the central Columbus campus Ohio State boasts some of the nation’s finest facilities for students, and we encourage you to explore them. Join the many students, faculty and staff who crisscross campus every day, and feel free to enter any building that interests you. Please don’t enter classrooms if a class is in session, however. You can complete this tour in about an hour and a half. Enjoy your visit! 1 The Ohio Union is the heart of 4 Mendenhall Laboratory first 8 The Oval, the open grassy area student life, featuring support for more opened in 1905 and is the current stretching from Thompson Library to than 1,200 student organizations, an home of the Department of Geological College Road, has symbolized Ohio instructional kitchen, the Archie M. Griffin Sciences. Check out the “fossil-like” State to students and visitors for Grand Ballroom, meeting rooms and event design of the floor in the main lobby. generations. At the heart of campus, spaces, Sloopy’s Diner and other eating This building also houses the Writing the Oval is a favorite place for reading, options, a retail shop, and places to study Center, where the university community relaxing and meeting friends. Legend and relax. Also located at the Ohio Union: gets help with research papers, lab has it that if you take the “Long Walk” Undergraduate Admissions Visits and reports, dissertations and resumes. from the seal at the east end to the Events, Student Life Multicultural Center, William Oxley Thompson statue on the satellite office for the alumni association 5 Hagerty Hall, home of the World west end while holding hands with your and Student Life Off-Campus and Media and Culture Center, houses loved one, you’ll be together forever. -

Beyond the Classroom

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM College life isn’t all about lecture halls and note-taking. From hanging out in residence halls to exploring downtown Columbus, and from getting involved in student organizations to taking advantage of health and wellness resources, Ohio State students have hundreds of opportunities beyond the classroom to learn, get involved and just have fun. University Housing tivities, residence halls encourage students to find their fit at Ohio State. Students can also consider joining MUNDO housing.osu.edu (Multicultural Understanding through Nontraditional Discovery Residence halls are “home,” places to study and students’ Opportunities), the Residence Halls Advisory Council (RHAC), the springboards for involvement at the university. Students living Black Student Association (BSA) or Allies for Diversity. in residence halls have opportunities to create friendships and University Housing and University Dining Services are two of the participate in all that Ohio State has to offer. Living in residence largest employers of undergraduate students on campus. halls also helps make a large university feel smaller. Students are able to arrange their work schedule around classes and enjoy the advantages of working where they live or dine. Learning communities Housing contracts Learning communities provide students with a friendly, sup- portive and challenging environment within the larger campus Upon signing their housing contracts, students commit them- community. These communities are designed with learning— selves to one academic year, from autumn semester through and fun—in mind. While living with others who share similar spring semester. Summer contracts are issued separately. academic, cultural or lifestyle interests, students collaboratively Students should become familiar with the provisions of the extend learning beyond the classroom through hands-on housing contract, the regulations that pertain to living units and experiences and by participating in structured programs that general housing policies. -

A Survey of Aed Locations at the Columbus Campus of the Ohio State University

2013 The Ohio State University Report prepared by Dana Keester, Graduate Student in Integrated Systems Engineering Report prepared for and edited by Dr. Carolyn Sommerich, Integrated Systems Engineering December 2013 A SURVEY OF AED LOCATIONS AT THE COLUMBUS CAMPUS OF THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Disclaimer: This report reflects the opinions of the authors and does not reflect opinions or policy of Ohio State University’s Department of Public Safety. 0 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Background Information .................................................................................................................................................... 2 State of the Program at the Ohio State University .................................................................................................................. 3 How many are there? ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Where are they? ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Opportunities for improvement ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Mounting locations ....................................................................................................................................................... -

An Encyclopedia of Pathbreaking Women at the Ohio State University

An Encyclopedia of Pathbreaking Women at The Ohio State University Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................... 1 An Encyclopedia of Pathbreaking Women at The Ohio State University ........................... 6 Background of Project and Request for Assistance ......................................................................... 6 An Encyclopedia of Pathbreaking Women at The Ohio State University ........................... 8 Women are People, Too: The Early Years at The Ohio State University, 1873-1912 .... 8 President Canfield ................................................................................................................................................... 9 William Oxley Thompson ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Pathbreakers ................................................................................................................................................. 11 Alice and Harriet Townshend ............................................................................................................................. 11 Miss Powers and the “Gab Room” Women .................................................................................................... 11 “Eve” ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

OSUL Folio Fall-2014.Pdf (3.301Mb)

olio University Libraries fall 2014 f Engaging with the Future Fall semester is an exciting time at The to support the inventive and unique Ohio State University. From the first day programs we offer today. Your gift can of classes, our libraries are filled with support the creation of new, dynamic new and returning students diligently library services in the 21st century and conducting research and taking full beyond. advantage of our digital resources, distinctive collections and traditional print We continue to enhance our role as materials. Our librarians and staff not only an “intellectual crossroads,” using our respond to basic reference questions, but spaces and collection to foster lifelong also engage in research consultations as learning. Two very different exhibitions information needs become more complex currently on display at the Thompson and require greater levels of expertise. Library Gallery and the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum mark the 50th We are moving forward with marketing anniversary of the signing of the Civil a suite of services that will eventually be Rights Act and the story of the movement integrated into our Research Commons, throughout our history. opening in the 18th Avenue Library in early 2016. Interdisciplinary collaboration is I want to congratulate my colleagues critically important as the university seeks who are highlighted in this issue as we transformative solutions to the Discovery recognize career milestones as they Themes being addressed across campus— are promoted, awarded tenure, and energy and environment, food production recognized by their peers for a wide and security, and health and wellness. The range of accomplishments.