Georgia's Runoff Election System Has Run Its Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Ernest Vandiver, Jr

OH Vandiver 01C Samuel Ernest Vandiver, Jr. interviewed by Mel Steeley and Ted Fitzsimmons Date: 6/25/86 Cassettes #439 (56 minutes) COPY OF ORIGINAL INTERVIEW ORIGINAL AT WEST GEORGIA UNIVERSITY Side One Fitzsimmons: Governor, we were talking about the integration of the university, and you said in making a decision you talked to a number of people, and among them Senator [Richard Brevard, Jr.] Russell. What was his advice? Vandiver: Well, I think you probably know what his situation was. He had fought these battles in the Senate for many, many years. And, of course, he knew from his practice of law and his familiarity with the law that I had no choice except to follow the law. That I couldn't, if I had defied the court, then I had no choice except to try to get the state of Georgia to secede again from the Union. And we'd tried that once and hadn't done too well that time. And so he knew that I had no choice. One thing that Betty [Sybil Elizabeth] Vandiver and I have talked about a great deal was her father was a federal judge; he was a judge of the northern district of Georgia. And he never had to deal with this situation. He knew it was probably coming, but he became ill with cancer, and he died in 1955 before this situation ever came before his court. And we've thought about it many times, that the Lord was kind to him. He would have had to rule in such a way that it would have been extremely difficult for him. -

Hugh M. Gillis Papers

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Finding Aids 1995 Hugh M. Gillis papers Zach S. Henderson Library. Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/finding-aids Part of the American Politics Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Zach S. Henderson Library. Georgia Southern University, "Hugh M. Gillis papers" (1995). Finding Aids. 10. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/finding-aids/10 This finding aid is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUGH M. GILLIS PAPERS FINDING AID OVERVIEW OF COLLECTION Title: Hugh M. Gillis papers Date: 1957-1995 Extent: 1 Box Creator: Gillis, Hugh M., 1918-2013 Language: English Repository: Zach S. Henderson Library Special Collections, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA. [email protected]. 912-478-7819. library.georgiasouthern.edu. Processing Note: Finding aid revised in 2020. INFORMATION FOR USE OF COLLECTION Conditions Governing Access: The collection is open for research use. Physical Access: Materials must be viewed in the Special Collections Reading Room under the supervision of Special Collections staff. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use: In order to protect the materials from inadvertent damage, all reproduction services are performed by the Special Collections staff. All requests for reproduction must be submitted using the Reproduction Request Form. Requests to publish from the collection must be submitted using the Publication Request Form. Special Collections does not claim to control the rights to all materials in its collection. -

Social Media Use in Georgia Gubernatorial Elections

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Honors College Theses 2021 The New Open Forum: Social Media Use in Georgia Gubernatorial Elections John Mack Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the American Politics Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Mack, John, "The New Open Forum: Social Media Use in Georgia Gubernatorial Elections" (2021). Honors College Theses. 615. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/615 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The New Open Forum: Social Media Use in Georgia Gubernatorial Elections An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Political Science and International Studies By: John Mack Under the mentorship of Dr. Patrick Novotny ABSTRACT In 2018, Georgia saw one of the most contested elections in recent memory with Brian Kemp narrowly defeating Stacey Abrams. As a part of that election, social media would play a critical role in how campaigns are run. This thesis takes a look at previous literature on voter turnout and social media. This thesis asks: How did the campaigns use social media to spread their message, and in what stage of the election was social media most effective? To answer that question this thesis features a content analysis of Facebook posts and Tweets from the 2018 elections compared to posts in the 2014 elections to answer my question and to see how campaigning on social media has evolved since 2014. -

2017 Spring Commencement

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Commencement Programs Office of Student Affairs Spring 2017 2017 Spring Commencement Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/commencement- programs Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "2017 Spring Commencement" (2017). Commencement Programs. 3. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/commencement-programs/3 This brochure is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Student Affairs at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EIGHTY-NINTH ANNUAL Spring Commencement GRADUATE UNDERGRADUATE Friday, May 5, 2017 Saturday, May 6, 2017 1:00 P.M. 9:00 A.M. Hanner Fieldhouse Paulson Stadium 590 Herty Drive 203 Lanier Drive Statesboro, Georgia Statesboro, Georgia Georgia Southern University 1 GRADUATE CEREMONY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS FACULTY MARSHALS Jack N. Averitt College of Graduate Studies JAMES M. LOBUE, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Chemistry and Biochemistry DEBORAH M. THOMAS, Ph.D., Associate Dean of Undergraduate Teacher Education, College of Education and Associate Professor, Teaching and Learning College of Business Administration EDDIE METREJEAN, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Accountancy L. DWIGHT SNEATHEN, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Accountancy College of Education MISSY BENNETT, Ed.D., Professor, Teaching and Learning ANTONIO PARTIDA GUTIERREZ DE BLUME, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Curriculum, Foundations and Reading Allen E. Paulson College of Engineering and ANDREW A. ALLEN, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Computer Sciences Information Technology CHRISTOPHER A. KADLEC, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Information Technology College of Health and Human Sciences LI LI, Ph.D., Professor, Health and Kinesiology MARIAN M. -

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr

Harold Paulk (Hal) Henderson, Sr. Oral History Collection Series I: Ellis Arnall OH ARN 02 S. Ernest Vandiver, Jr. Interviewed by Harold Paulk (Hal) Henderson, Sr. Date: May 23, 1981 CD: OH ARN 02, Tracks 1-6; 0:53:23 minutes Cassette: OH ARN 02, 0:53:23 minutes (Sides 1 and 2) [CD: Track 1] [Cassette: Side 1] HENDERSON: Governor, let me begin by asking you: when did you decide to enter the 1966 gubernatorial campaign? VANDIVER: When did I decide to end it? HENDERSON: Enter it. Get into it. VANDIVER: Oh, enter it. HENDERSON: Yes. VANDIVER: Oh, well, I left office in 1963, and I think I left office in good political shape. We endured some pretty hard times—it was during the period of the first integration of the schools. But I think there was general approval of the way that we handled the situation. I still had a lot of strong political ties, and I felt like that I’d have a real good chance of winning the gubernatorial race in 1966. At that time, of course, we were limited to one term. And it later changed to two terms by constitutional amendment. I kept up on political associations during 2 this period. I had suffered a heart attack during my term in office, in 1960. I had some residual angina, but as long as I was able to set my own pace, I pretty well got along all right. As the gubernatorial campaign concourse[?] grew closer, I got into a position where I was not able to control my diet. -

AFY 2018 Governor's Budget Report

THE GOVERNOR’S BUDGET REPORT Amended Fiscal Year 2018 Governor Nathan Deal THE GOVERNOR’S BUDGET REPORT ___________________________________________________ AMENDED FISCAL YEAR 2018 NATHAN DEAL, GOVERNOR STATE OF GEORGIA TERESA A. MACCARTNEY DIRECTOR OFFICE OF PLANNING AND BUDGET You may visit our website for additional information and copies of this document. opb.georgia.gov Table of Contents Introduction Department of Behavioral Health and Governor’s Letter . 1 Developmental Disabilities . 57 Budget Highlights . 5 Department of Community Affairs. 62 Department of Community Health . 67 Financial Summaries Department of Community Supervision . 73 Georgia Estimated State Revenues Amended FY Department of Corrections. 77 2018 . 9 Department of Defense . 79 Georgia Revenues: FY 2015 - FY 2017 and Department of Driver Services. 81 Estimated FY 2018. 10 Department of Early Care and Learning . 83 Georgia Estimated Revenues. 12 Department of Economic Development . 85 Summary of Appropriations . 13 Department of Education . 88 Summary of Appropriations: By Policy Area . 15 Employees' Retirement System of Georgia . 95 State Funds by Policy Area. 18 State Forestry Commission . 97 Lottery Funds . 19 Office of the Governor . 99 Tobacco Settlement Funds. 20 Department of Human Services . 102 Transportation Funds . 21 Commissioner of Insurance. 111 Summary of Statewide Budget Changes. 22 Georgia Bureau of Investigation . 114 Department of Juvenile Justice . 117 Department Summaries Department of Labor. 119 Legislative Department of Law . 121 Georgia Senate . 26 Department of Natural Resources . 123 Georgia House of Representatives. 28 State Board of Pardons and Paroles . 127 General Assembly . 30 State Properties Commission . 129 Department of Audits and Accounts . 32 Georgia Public Defender Council . 131 Judicial Department of Public Health . -

Fork in the Road

Sunday Edition July 22, 2018 BARTOW COUNTY’S ONLY DAILY NEWSPAPER $1.50 New GDOT headquarters on Cartersville pace for January completion Council BY JAMES SWIFT The roughly 30,000-square-foot building is postpones [email protected] being constructed in the Highland 75 industrial park, right in front of the voestalpine Automotive Brunch Bill Substantial progress is being made on the new Components facility. Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) GDOT broke ground on the new district office District 6 headquarters in White, which is expected in March. The facility is about eight miles north of referendum to be finished in about six months. the current GDOT District 6 office, which is lo- “We have already erected the steel structure,” cated slightly south of Cartersville at 500 Joe JAMES SWIFT/DAILY TRIBUNE NEWS for a year Construction is ongoing for the $6 million GDOT District 6 said GDOT District 6 Communications Coordina- Frank Harris Parkway. headquarters in White; officials say the facility will be finished by tor Mohamed Arafa. “The project is on schedule SEE GDOT, PAGE 7A BY NEIL B. MCGAHEE early 2019. to be entirely completed around January of 2019.” [email protected] The Cartersville City Council took action Thursday to correct an error that came down from At- Hebert to lanta. In February, the Georgia Gen- eral Assembly passed a law com- present FORK IN THE ROAD monly known as the Brunch Bill, which gave local municipalities that already have Sunday alcohol ‘Bartow sales the option to decide through a ballot referendum if they would like to roll back Sunday on- County’s premise consumption sale hours from 12:30 p.m. -

Election Summary

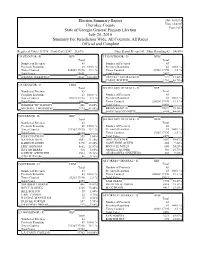

Election Summary Report Date:01/02/18 Cherokee County Time:14:42:07 Page:1 of 4 State of Georgia General Primary Election July 20, 2010 Summary For Jurisdiction Wide, All Counters, All Races Official and Complete Registered Voters 117196 - Cards Cast 25347 21.63% Num. Report Precinct 43 - Num. Reporting 43 100.00% US SENATOR - R REP LT GOVERNOR - D DEM Total Total Number of Precincts 43 Number of Precincts 43 Precincts Reporting 43 100.0 % Precincts Reporting 43 100.0 % Times Counted 22420/117196 19.1 % Times Counted 2926/117196 2.5 % Total Votes 18651 Total Votes 2487 JOHNNY ISAKSON (I) 18651 100.00% TRICIA C. MCCRACKEN 777 31.24% CAROL PORTER 1710 68.76% US SENATOR - D DEM Total SECRETARY OF STATE - R REP Number of Precincts 43 Total Precincts Reporting 43 100.0 % Number of Precincts 43 Times Counted 2927/117196 2.5 % Precincts Reporting 43 100.0 % Total Votes 2593 Times Counted 22420/117196 19.1 % RAKEIM "RJ" HADLEY 468 18.05% Total Votes 19856 MICHAEL THURMOND 2125 81.95% BRIAN KEMP (I) 10992 55.36% DOUG MACGINNITIE 8864 44.64% GOVERNOR - R REP Total SECRETARY OF STATE - D DEM Number of Precincts 43 Total Precincts Reporting 43 100.0 % Number of Precincts 43 Times Counted 22420/117196 19.1 % Precincts Reporting 43 100.0 % Total Votes 22130 Times Counted 2926/117196 2.5 % JEFF CHAPMAN 355 1.60% Total Votes 2479 NATHAN DEAL 4692 21.20% GAIL BUCKNER 1007 40.62% KAREN HANDEL 8198 37.04% GARY HORLACHER 244 9.84% ERIC JOHNSON 4862 21.97% MICHAEL MILLS 600 24.20% RAY MCBERRY 410 1.85% ANGELA MOORE 390 15.73% JOHN W. -

Maintaining Judicial Independence in Drug Courts

Er!'Wyr "Iir & Maintaining Judicial Independence in Drug Courts 06-08GBJ_Cover.indd 1 5/22/2008 9:12:32 AM ( 3 3 44 ) 1 ? 4 1, 0 ( .3 ' 37 $ 1 0 [ 3A ! 37 $ 3@ 4 [ 4 ( 4 4 5 4 6 4 5 [ 3 4 5 0 - 1 A " 37 $ = 1 3A 0 1 3 B 4C : + D 1 1 E 0 0 [ 3 6 7 4 4 4 4 0 50 C : 4 0 5 $ [ 3 3 4 6 4 $3 0 $ 0 $ 4 7 E 3 J '&&K 5 5 5 5 5 7 5 @ 4 3 43 1 . $$ 43 1 . $ 4 @ 4 5 = 5 = 1 4 6 50 33 / . $$ 33 / . $ 4 33 )(, 1 50 @ @ 4 3= 43 6 /E (3 5 F G 9 3 3 4 (3 1 3 6 3 5 @ 7 @ ( 5 F 6 3 5 ( @ D 0 D 5 33 5 . $ 4 ;6 4 5 /7 . 5 3 /7 . < / 3 4 0 4 @ 7 ) 4 4 . \ 4 4 51, 4 9 I1 . $$ I1 . $ 4 $$ ) @ , 7 < . 33 . 4 1 43 . 4 6 4 . 8 /E 8 4 8= 3 . $$ 8= 3 . $ 4 0 ( 4 3 ( 4 6 3 14 / 3 @ 4 7 3 3 1 4 4 7 6 / $ 1 1 3 : 43 4 : ; 4 ( 3 5 $ 3 8= 5 )0 0 $ 1, ( 3 )< 76 4 , ( ( 3 ) 1, 8//9'!&+>"!&+ 0 1 $ [ 3 0 4 4 1 $ 1 4 5 ) $ 6 7 , 6 5 31 7 74 1 73 4 $ $ 8 8 9 33 3 1 # # !"!# # $ !%%&' # ( )*+", -!-.%%%! / '.***.+#+.'%-% 06-08GBJ_Cover.indd 2 5/22/2008 9:12:38 AM 06-08gbj.qxp 5/22/2008 12:40 PM Page 1 June 2008 Volume 13 Number 7 GBJ Legals 42 14 Law Day Rules 14 Maintaining Judicial in Glynn County! Independence in Drug Courts by Linda T. -

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr. Oral History Collection OH Vandiver 22 George Thornewell Smith Interviewed by Dr. Harold Paulk Henderson Date: 03-23-94 Cassette #473 (44 Minutes) EDITED BY DR. HENDERSON Side One Henderson: This is an interview with former Lieutenant Governor George T. [Thornewell] Smith in his law office in Marietta, Georgia. The date is March 23, 1994, and I am Dr. Hal Henderson. Good morning, Governor Smith. Smith: Good morning, Dr. Henderson. Henderson: Thank you for granting me this interview. Smith: It's my pleasure, sir. Henderson: You served in the state House of Representatives during the [Marvin] Griffin administration . Smith: Not during the Griffin administration. Henderson: Not during the Griffin administration? Smith: No, I started--my first year in the House of Representatives was 1959, the first year of Governor [Samuel Ernest] Vandiver's [Jr.] term as governor. Henderson: Okay. All right. Did you support Ernest Vandiver in his race for lieutenant governor in 1954? Smith: Yes, I did. Henderson: How actively did you support him? Smith: I wasn't active. I voted for him. That was probably all that I did in 1954. 2 Henderson: Why did you support him in that campaign? Smith: I thought he was the best man in the race. Henderson: He is lieutenant governor at a time when [Samuel] Marvin Griffin [Sr.] was governor. What are your recollections of the Marvin Griffin administration? Smith: Well, the recollection was subsequent to his administration rather than during his administration because all of the scandal came out after the four years was over with. -

George T. Smith Has Grown Accustomed to Standing out in A

has grown accustomed to standing out in a crowd By Janet Jones Kendall t the age of 13, Smith’s father, on 125 acres of sand land in southwest George Cleveland Smith, became Georgia, there wasn’t much of a future. I A seriously ill, making it necessary noticed the lawyers in Camilla had the for the then seventh grader to drop out of best cars and were the best dressed and school to work on the farm and help sup- when I realized that I said, ‘I want to be a port his family. Under those circumstances, lawyer.’ From then on, I wanted to go to Smith notes, most teens during that time law school. But I had no idea I’d actually would have never gone back to school. be able to go. It was a dream come true However, thanks to his mother Rosa Gray for me that I did." Smith, who was "bound and determined Not only did Smith become a lawyer, that I was going back," Smith re-entered graduating from the University of Georgia school, starting the eighth grade at the age School of Law in 1948, he went on to of 18. And, despite being taunted by his make Georgia history by becoming the younger classmates (who referred to him as George T. Smith in front of his portrait hanging in only person to win contested elections in "Grandpa"), Smith did indeed get his high the State Capitol in Atlanta. Photo courtesy of all three branches of state government. school diploma when he graduated at the Laura Heath Photography. -

Interview with George T. Smith August 19, 1992 & August 20, 1992

Georgia Government Documentation Project Series B: Public Figures Interview with George T. Smith August 19, 1992 & August 20, 1992 Copyright Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library DISCLAIMER: Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account. It reflects personal opinion offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. RIGHTS: Unless otherwise noted, all property and copyrights, including the right to publish or quote, are held by Georgia State University (a unit of the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia). This transcript is being provided solely for the purpose of teaching or research. Any other use--including commercial reuse, mounting on other systems, or other forms of redistribution--requires permission of the appropriate office at Georgia State University. In addition, no part of the transcript may be quoted for publication without written permission. To quote in print, or otherwise reproduce in whole or in part in any publication, including on the Worldwide Web, any material from this collection, the researcher must obtain permission from (1) the owner of the physical property and (2) the holder of the copyright. Persons wishing to quote from this collection should consult the reference archivist to determine copyright holders for information in this collection.