Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Granite Mansion: Georgia's Governor's Mansion 1924-1967

The Granite Mansion: Georgia’s Governor’s Mansion 1924-1967 Documentation for the proposed Georgia Historical Marker to be installed on the north side of the road by the site of the former 205 The Prado, Ansley Park, Atlanta, Georgia June 2, 2016 Atlanta Preservation & Planning Services, LLC Georgia Historical Marker Documentation Page 1. Proposed marker text 3 2. History 4 3. Appendices 10 4. Bibliography 25 5. Supporting images 29 6. Atlanta map section and photos of proposed marker site 31 2 Proposed marker text: The Granite Governor’s Mansion The Granite Mansion served as Georgia’s third Executive Mansion from 1924-1967. Designed by architect A. Ten Eyck Brown, the house at 205 The Prado was built in 1910 from locally- quarried granite in the Italian Renaissance Revival style. It was first home to real estate developer Edwin P. Ansley, founder of Ansley Park, Atlanta’s first automobile suburb. Ellis Arnall, one of the state’s most progressive governors, resided there (1943-47). He was a disputant in the infamous “three governors controversy.” For forty-three years, the mansion was home to twelve governors, until poor maintenance made it nearly uninhabitable. A new governor’s mansion was constructed on West Paces Ferry Road. The granite mansion was razed in 1969, but its garage was converted to a residence. 3 Historical Documentation of the Granite Mansion Edwin P. Ansley Edwin Percival Ansley (see Appendix 1) was born in Augusta, GA, on March 30, 1866. In 1871, the family moved to the Atlanta area. Edwin studied law at the University of Georgia, and was an attorney in the Atlanta law firm Calhoun, King & Spalding. -

Samuel Ernest Vandiver, Jr

OH Vandiver 01C Samuel Ernest Vandiver, Jr. interviewed by Mel Steeley and Ted Fitzsimmons Date: 6/25/86 Cassettes #439 (56 minutes) COPY OF ORIGINAL INTERVIEW ORIGINAL AT WEST GEORGIA UNIVERSITY Side One Fitzsimmons: Governor, we were talking about the integration of the university, and you said in making a decision you talked to a number of people, and among them Senator [Richard Brevard, Jr.] Russell. What was his advice? Vandiver: Well, I think you probably know what his situation was. He had fought these battles in the Senate for many, many years. And, of course, he knew from his practice of law and his familiarity with the law that I had no choice except to follow the law. That I couldn't, if I had defied the court, then I had no choice except to try to get the state of Georgia to secede again from the Union. And we'd tried that once and hadn't done too well that time. And so he knew that I had no choice. One thing that Betty [Sybil Elizabeth] Vandiver and I have talked about a great deal was her father was a federal judge; he was a judge of the northern district of Georgia. And he never had to deal with this situation. He knew it was probably coming, but he became ill with cancer, and he died in 1955 before this situation ever came before his court. And we've thought about it many times, that the Lord was kind to him. He would have had to rule in such a way that it would have been extremely difficult for him. -

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr. Oral History Collection OH Vandiver 23 George Dekle Busbee Interviewed by Dr. Harold Paulk Henderson Date: 03-17-94 Cassette # 474 (26 Minutes, Side One Only) EDITED BY DR. HENDERSON Side One Henderson: This is an interview with former Governor George D. [Dekle] Busbee in his law office in Atlanta. The date is March 17, 1994. I am Dr. Hal Henderson. Good afternoon, Governor Busbee. Busbee: Good day. Henderson: Thank you very much for granting me this interview. Busbee: I'm delighted. Henderson: You served in the state House of Representatives the last two years of the [Samuel] Marvin Griffin [Sr.] administration and you served all four years of [Samuel] Ernest Vandiver's [Jr.] administration. Let me begin by asking you: what was your impression of the Marvin Griffin administration? Busbee: Well, of course, if you had to choose sides Marvin wouldn't have said that I was in his camp. I will say, however, that I was reminiscing with some people that served in the legislature with me back then and have served since I was governor, and we don't think it's as much fun as it used to be. I think he was a very colorful character and we had a great time, but I think that was former days for Georgia; that's not the era that we're in now. Henderson: Okay. How would you describe the relationship between Lieutenant Governor Vandiver and Governor Marvin Griffin? 2 Busbee: Well, the first real bitter fight that I became engaged in as a legislator was during the time that I was there [and] Marvin Griffin was governor, and we had the rural roads fight. -

Hugh M. Gillis Papers

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Finding Aids 1995 Hugh M. Gillis papers Zach S. Henderson Library. Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/finding-aids Part of the American Politics Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Zach S. Henderson Library. Georgia Southern University, "Hugh M. Gillis papers" (1995). Finding Aids. 10. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/finding-aids/10 This finding aid is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUGH M. GILLIS PAPERS FINDING AID OVERVIEW OF COLLECTION Title: Hugh M. Gillis papers Date: 1957-1995 Extent: 1 Box Creator: Gillis, Hugh M., 1918-2013 Language: English Repository: Zach S. Henderson Library Special Collections, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA. [email protected]. 912-478-7819. library.georgiasouthern.edu. Processing Note: Finding aid revised in 2020. INFORMATION FOR USE OF COLLECTION Conditions Governing Access: The collection is open for research use. Physical Access: Materials must be viewed in the Special Collections Reading Room under the supervision of Special Collections staff. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use: In order to protect the materials from inadvertent damage, all reproduction services are performed by the Special Collections staff. All requests for reproduction must be submitted using the Reproduction Request Form. Requests to publish from the collection must be submitted using the Publication Request Form. Special Collections does not claim to control the rights to all materials in its collection. -

January 11, 1955: Marvin Griffin Sworn in As Governor Learn More

January 11, 1955: Marvin Griffin Sworn In as Governor Learn More Suggested Readings Scott E. Buchanan, Some of the People Who Ate My Barbecue Didn't Vote for Me (Nashville, Tenn.: Vanderbilt University Press, 2011). James F. Cook, The Governors of Georgia, 1754-2004, 3d ed. (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 2005). Harold P. Henderson and Gary L. Roberts, eds., Georgia Governors in an Age of Change: From Ellis Arnall to George Busbee (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988). “Marvin Griffin (1907-1982).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-827&sug=y National Governor’s Association: http://www.nga.org/cms/home/governors/past-governors- bios/page_georgia/col2-content/main-content-list/title_griffin_samuel.html Georgia Busbee: Marvin Griffin 1987 interview http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Multimedia.jsp?id=m-2034 www.todayingeorgiahistory.org January 11, 1955: Marvin Griffin Sworn in as Governor Learn More Image Credits Ag Hill Scene with buildings and students Image courtesy of UGA Photographic Services, photographer Andrew Davis Tucker Brown v. Board document, 301669 National Archives and Records Administration, Accessed through archives.gov Camden County Training School Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia Collection, cam032 Carving with Trees Courtesy of the Stone Mountain Press Office Floyd County classroom, 1950s Courtesy of Georgia Archives, Vanishing Georgia Collection, flo154 www.todayingeorgiahistory.org Governor Griffin addresses GA Assembly Courtesy of Georgia -

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr

Harold Paulk (Hal) Henderson, Sr. Oral History Collection Series I: Ellis Arnall OH ARN 02 S. Ernest Vandiver, Jr. Interviewed by Harold Paulk (Hal) Henderson, Sr. Date: May 23, 1981 CD: OH ARN 02, Tracks 1-6; 0:53:23 minutes Cassette: OH ARN 02, 0:53:23 minutes (Sides 1 and 2) [CD: Track 1] [Cassette: Side 1] HENDERSON: Governor, let me begin by asking you: when did you decide to enter the 1966 gubernatorial campaign? VANDIVER: When did I decide to end it? HENDERSON: Enter it. Get into it. VANDIVER: Oh, enter it. HENDERSON: Yes. VANDIVER: Oh, well, I left office in 1963, and I think I left office in good political shape. We endured some pretty hard times—it was during the period of the first integration of the schools. But I think there was general approval of the way that we handled the situation. I still had a lot of strong political ties, and I felt like that I’d have a real good chance of winning the gubernatorial race in 1966. At that time, of course, we were limited to one term. And it later changed to two terms by constitutional amendment. I kept up on political associations during 2 this period. I had suffered a heart attack during my term in office, in 1960. I had some residual angina, but as long as I was able to set my own pace, I pretty well got along all right. As the gubernatorial campaign concourse[?] grew closer, I got into a position where I was not able to control my diet. -

The State Flag of Georgia: the 1956 Change in Its Historical Context

The State Senate Senate Research Office Bill Littlefield 204 Legislative Office Building Telephone Managing Director 18 Capitol Square 404/ 656 0015 Atlanta, Georgia 30334 Martha Wigton Fax Director 404/ 657 0929 The State Flag of Georgia: The 1956 Change In Its Historical Context Prepared by: Alexander J. Azarian and Eden Fesshazion Senate Research Office August 2000 Table of Contents Preface.....................................................................................i I. Introduction: National Flags of the Confederacy and the Evolution of the State Flag of Georgia.................................1 II. The Confederate Battle Flag.................................................6 III. The 1956 Legislative Session: Preserving segregation...........................................................9 IV. The 1956 Flag Change.........................................................18 V. John Sammons Bell.............................................................23 VI. Conclusion............................................................................27 Works Consulted..................................................................29 Preface This paper is a study of the redesigning of Georgia’s present state flag during the 1956 session of the General Assembly as well as a general review of the evolution of the pre-1956 state flag. No attempt will be made in this paper to argue that the state flag is controversial simply because it incorporates the Confederate battle flag or that it represents the Confederacy itself. Rather, this paper will focus on the flag as it has become associated, since the 1956 session, with preserving segregation, resisting the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, and maintaining white supremacy in Georgia. A careful examination of the history of Georgia’s state flag, the 1956 session of the General Assembly, the designer of the present state flag – John Sammons Bell, the legislation redesigning the 1956 flag, and the status of segregation at that time, will all be addressed in this study. -

George T. Smith Has Grown Accustomed to Standing out in A

has grown accustomed to standing out in a crowd By Janet Jones Kendall t the age of 13, Smith’s father, on 125 acres of sand land in southwest George Cleveland Smith, became Georgia, there wasn’t much of a future. I A seriously ill, making it necessary noticed the lawyers in Camilla had the for the then seventh grader to drop out of best cars and were the best dressed and school to work on the farm and help sup- when I realized that I said, ‘I want to be a port his family. Under those circumstances, lawyer.’ From then on, I wanted to go to Smith notes, most teens during that time law school. But I had no idea I’d actually would have never gone back to school. be able to go. It was a dream come true However, thanks to his mother Rosa Gray for me that I did." Smith, who was "bound and determined Not only did Smith become a lawyer, that I was going back," Smith re-entered graduating from the University of Georgia school, starting the eighth grade at the age School of Law in 1948, he went on to of 18. And, despite being taunted by his make Georgia history by becoming the younger classmates (who referred to him as George T. Smith in front of his portrait hanging in only person to win contested elections in "Grandpa"), Smith did indeed get his high the State Capitol in Atlanta. Photo courtesy of all three branches of state government. school diploma when he graduated at the Laura Heath Photography. -

A Condensed History of the Stone Mountain Carving

A Condensed History of the Stone Mountain Carving Copyright © 2017 Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. Atlanta History Center 130 West Paces Ferry Road NW Atlanta, Georgia, 30305. www.atlantahistorycenter.com Executive Summary: Condensed History of the Stone Mountain Carving The carving on the side of Stone Mountain has a controversial history that involves strong connections to white supremacy, Confederate Lost Cause mythology, and anti-Civil Rights sentiments. From the beginning of efforts to create the carving in 1914, early proponents of the carving had strong connections to the Ku Klux Klan and openly supported Klan politics. Helen Plane, leader of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and credited with beginning efforts to create the initial carving, openly praised the Klan and even proposed Klansmen be incorporated in the carving. Sam Venable, owner of Stone Mountain, sanctioned Klan meetings on the mountain and remained highly involved with the group for many years. These are just a two of the early carving proponents involved with the white supremacist organization- the carver, Gutzon Borglum, and others were also involved. Given the influence of white supremacists, the Stone Mountain carving effort carried with it Confederate Lost Cause sentiments from its beginning. Efforts at rewriting Confederate history as a moral victory and pining for the supposedly morally superior society of the romanticized Old South were at the center of the motivations behind the carving. Although the carving was not again pursued after the collapse of the initial effort until half a century after it was begun, Lost Cause sentiments remained. Governor Marvin Griffin, an overt supporter of segregation, promised to resume the carving if elected during his campaign for governor. -

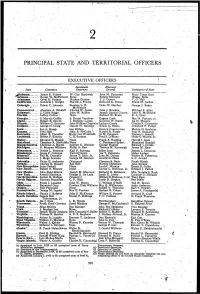

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

Georgia's Runoff Election System Has Run Its Course

GEORGIA’S RUNOFF ELECTION SYSTEM HAS RUN ITS COURSE Graham Paul Goldberg Georgia requires candidates to earn a majority of votes in their party’s primary to win elected office. The majority-vote requirement—passed by the General Assembly in 1964—is stained by racially-fraught politics of the era, and even its alleged “good government” goals are now antiquated. This Note explores the history of Georgia’s majority-vote requirement, examines two legal challenges to the law, and analyzes its flaws and virtues. Finally, this Note demonstrates that more appealing alternatives to the majority-vote requirement exist and recommends that Georgia replace its current runoff election system with either ranked choice voting or a forty-percent threshold-vote requirement. J.D. Candidate, 2020, University of Georgia School of Law; B.S.B.A., B.S.P.P., 2014, Georgia Institute of Technology. I would like to thank Professor Lori Ringhand for gifting me this Note topic. I would also like to thank Michael Ackerman, Alex Weathersby, Caroline Harvey (my ENE partner-in-crime), Amy Elizabeth Shehan, and the Volume 54 Editorial Board for their invaluable support throughout the editing process. And last but not least, thank you Mom and Dad for everything. 1063 1064 GEORGIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 54:1063 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION.........................................................................1065 II. HISTORY OF GEORGIA’S MAJORITY-VOTE REQUIREMENT .......1069 III. PAST CHALLENGES TO GEORGIA’S PRIMARY RUNOFF SYSTEM .............................................................................1073 A. BROOKS CHALLENGE .....................................................1073 B. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE CHALLENGE ..........................1079 IV. THE FLAWS AND VIRTUES OF THE MAJORITY-VOTE REQUIREMENT ..................................................................1081 V. ALTERNATIVES TO THE MAJORITY-VOTE REQUIREMENT ........1084 A. -

Interview with George T. Smith August 19, 1992 & August 20, 1992

Georgia Government Documentation Project Series B: Public Figures Interview with George T. Smith August 19, 1992 & August 20, 1992 Copyright Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library DISCLAIMER: Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account. It reflects personal opinion offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. RIGHTS: Unless otherwise noted, all property and copyrights, including the right to publish or quote, are held by Georgia State University (a unit of the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia). This transcript is being provided solely for the purpose of teaching or research. Any other use--including commercial reuse, mounting on other systems, or other forms of redistribution--requires permission of the appropriate office at Georgia State University. In addition, no part of the transcript may be quoted for publication without written permission. To quote in print, or otherwise reproduce in whole or in part in any publication, including on the Worldwide Web, any material from this collection, the researcher must obtain permission from (1) the owner of the physical property and (2) the holder of the copyright. Persons wishing to quote from this collection should consult the reference archivist to determine copyright holders for information in this collection.