Race and Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soh6.6.11Newreleaseb

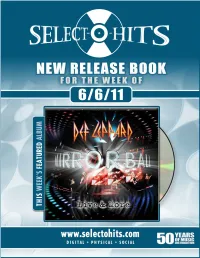

RETURNS WITH A THREE LP COLLECTION! MMMIIIRRRRRROOORRR BBBAAALLLLLL::: LLLIIIVVVEEE &&& MMMOOORRREEE This is the ULTIMATE live set! All of Def Leppard’s hits, recorded live for the first time ever, are on this 180 gram virgin vinyl, 3 LP collection. FOUR NEW SONGS ARE FEATURED, INCLUDING “UNDEFEATED,” THE CURRENT #1 SINGLE AT CLASSIC ROCK RADIO. TITLE: MIRROR BALL ‐ LIVE & MORE RELEASE DATE: 7/5/11 LABEL: MAILBOAT RECORDS UPC: 698268952003 CATALOG #: MBR 9520 CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO THE #1 SONG “UNDEFEATED” LP 1 LP 3 Rock! Rock (‘Til You Drop) Rock of Ages SUMMER TOUR DATES WITH SPECIAL GUEST HEART Rocket Let’s Get Rocked Animal June 15 West Palm Beach, FL July 23 New Orleans, LA Bonus Live: June 17 Tampa, FL July 24 San Antonio, TX C’mon C’mon Action June 18 Atlanta, GA August 8 Sturgis, SD Make Love Like A Man Bad Actress June 19 Orange Beach, AL August 10 St. Louis, MO Too Late For Love Undefeated June 22 Charlotte, NC August 13 Des Moines, IA Foolin’ June 24 Raleigh, NC August 16 Toronto, CAN Kings of the World June 25 Virginia Beach, VA August 17 Detroit, MI Nine Lives New Songs: June 26 Philadelphia, PA August 19 Louisville, KY Love Bites Undefeated June 29 Scranton, PA August 20 Pittsburgh, PA Kings of the World June 30 Boston, MA August 21 Buffalo, NY July 2 Uncasville, CT August 24 Cleveland, OH LP 2 It’s All About Believin’ July 3 Hershey, PA August 26 St. Paul, MN Rock On July 5 Milwaukee, WI August 27 Kansas City, MO Two Steps Behind July 7 Cincinnati, OH August 29 Denver, CO Bringin’ on the Heartbreak July 9 Washington, DC -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

The Titles Below Are Being Released for Record Store

THE TITLES BELOW ARE BEING RELEASED FOR RECORD STORE DAY (v.2.2 updated 4-01) ARTISTA TITOLO FORMATO LABEL LA DONNA IL SOGNO & IL GRANDE ¢ 883 2LP PICTURE WARNER INCUBO ¢ ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO LP SPACE AGE ¢ AL GREEN GREEN IS BLUES LP FAT POSSUM ¢ ALESSANDRO ALESSANDRONI RITMO DELL’INDUSTRIA N°2 LP BTF ¢ ALFREDO LINARES Y SU SONORA YO TRAIGO BOOGALOO LP VAMPISOUL LIVE FROM THE APOLLO THEATRE ¢ ALICE COOPER 2LP WARNER GLASGOW, FEB 19, 1982 SOUNDS LIKE A MELODY (GRANT & KELLY ¢ ALPHAVILLE REMIX BY BLANK & JONES X GOLD & 12" WARNER LLOYD) HERITAGE II:DEMOS ALTERNATIVE TAKES ¢ AMERICA LP WARNER 1971-1976 ¢ ANDREA SENATORE HÉRITAGE LP ONDE / ITER-RESEARCH ¢ ANDREW GOLD SOMETHING NEW: UNREALISED GOLD LP WARNER ¢ ANNIHILATOR TRIPLE THREAT UNPLUGGED LP WARNER ¢ ANOUSHKA SHANKAR LOVE LETTERS LP UNIVERSAL ¢ ARCHERS OF LOAF RALEIGH DAYS 7" MERGE ¢ ARTICOLO 31 LA RICONQUISTA DEL FORUM 2LP COLORATO BMG ¢ ASHA PUTHLI ASHA PUTHLI LP MR. BONGO ¢ AWESOME DRE YOU CAN'T HOLD ME BACK LP BLOCGLOBAL ¢ BAIN REMIXES 12'' PICTURE CIMBARECORD ¢ BAND OF PAIN A CLOCKWORK ORANGE LP DIRTER ¢ BARDO POND ON THE ELLIPSE LP FIRE ¢ BARRY DRANSFIELD BARRY DRANSFIELD LP GLASS MODERN ¢ BARRY HAY & JB MEIJERS THE ARTONE SESSION 10" MUSIC ON VINYL ¢ BASTILLE ALL THIS BAD BLOOD 2LP UNIVERSAL ¢ BATMOBILE BIG BAT A GO-GO 7'' COLORATO MUSIC ON VINYL I MISTICI DELL'OCCIDENTE (10° ¢ BAUSTELLE LP WARNER ANNIVERSARIO) ¢ BECK UNEVENTFUL DAYS (ST. VINCENT REMIX) 7" UNIVERSAL GRANDPAW WOULD (25TH ANNIVERSARY ¢ BEN LEE 2LP COLORATO LIGHTNING ROD DELUXE) ¢ BEN WATT WITH ROBERT WYATT SUMMER INTO WINTER 12'' CHERRY RED ¢ BERT JANSCH LIVE IN ITALY LP EARTH ¢ BIFFY CLYRO MODERNS 7'' COLORATO WARNER ¢ BLACK ARK PLAYERS GUIDANCE 12'' PICTURE VP GOOD TO GO ¢ BLACK LIPS FEAT. -

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

L the Charlatans UK the Charlatans UK Vs. the Chemical Brothers

These titles will be released on the dates stated below at physical record stores in the US. The RSD website does NOT sell them. Key: E = Exclusive Release L = Limited Run / Regional Focus Release F = RSD First Release THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE AUGUST 29TH ARTIST TITLE LABEL FORMAT QTY Sounds Like A Melody (Grant & Kelly E Alphaville Rhino Atlantic 12" Vinyl 3500 Remix by Blank & Jones x Gold & Lloyd) F America Heritage II: Demos Omnivore RecordingsLP 1700 E And Also The Trees And Also The Trees Terror Vision Records2 x LP 2000 E Archers of Loaf "Raleigh Days"/"Street Fighting Man" Merge Records 7" Vinyl 1200 L August Burns Red Bones Fearless 7" Vinyl 1000 F Buju Banton Trust & Steppa Roc Nation 10" Vinyl 2500 E Bastille All This Bad Blood Capitol 2 x LP 1500 E Black Keys Let's Rock (45 RPM Edition) Nonesuch 2 x LP 5000 They's A Person Of The World (featuring L Black Lips Fire Records 7" Vinyl 750 Kesha) F Black Crowes Lions eOne Music 2 x LP 3000 F Tommy Bolin Tommy Bolin Lives! Friday Music EP 1000 F Bone Thugs-N-Harmony Creepin' On Ah Come Up Ruthless RecordsLP 3000 E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone LP E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone CD E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone 2 x LP E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone CD E Marion Brown Porto Novo ORG Music LP 1500 F Nicole Bus Live in NYC Roc Nation LP 2500 E Canned Heat/John Lee Hooker Hooker 'N Heat Culture Factory2 x LP 2000 F Ron Carter Foursight: Stockholm IN+OUT Records2 x LP 650 F Ted Cassidy The Lurch Jackpot Records7" Vinyl 1000 The Charlatans UK vs. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

PDF (1.41 Mib)

B2 ARCADE WWW.THEHULLABALOO.COM THREE 6 MAFIA, 15 YEARS· LATER: .. :r '» THE INFLUENCE OF MYSTIC STYLEZ f t' BY ZACH YANOWITZ rel couldn't tell you half about this antichrist/Look into my eyes ASSISTANT ARCADE EDITOR tell me what you see/1he demonic man about s 」 。 イ ・ 」 イ ッ キ ゥ ウ ュ セ The J vast majority of Mystic Stylez is far too offensive for publication: • i.i There's something intrinsically off about a white boy from the These guys (and singular gal) were not messing around. Massachusetts suburbs reviewing what might be the hardest rap Despite the shocking lyrics and underground production, Tri- h'lbum of all time, but I'm going to give it a shot ple-6 made the most of its low budget 'lhe eerie minimalist beats _.. ,: The members of 'lhree 6 Mafia had a long journey before they sample church bells and graveyard ・ ヲ ヲ ・ 」 セ N producing sounds that '&gan winning Academy Awards and hanging out with Andy could be the score to a horror movie. Chopped-and-screwed vocals Milonakis. Brothers DJ Paul and Juicy J formed the group, which and minor piano chords emphasize the rising tension throughout %iginally included Lord Infamous (Da Scarecrow), Gangsta Boo, the album that settles with laidback '90s hoodrat tunes such as 't<oopsta Knicca and Crunchy Black Since then, they've lost all "Da Summa," a song about the simple yet still explicit pleasures of 1nembers but Paul and J - and most of their street creel, too - Memphis life. Call-and-response choruses and the high-cadence 'lfiut their early music is a very· different creature. -

Three 6 Mafia, We 'Bout to Ride

Three 6 Mafia, We 'Bout To Ride [DJ Paul: talking] yeah nigga the mother fuckin two time two time motherfuckin champions in this bitch I got another motherfuckin gold plaque on the wall now nigga now tell me what you think about that look me in my eyes and tell me nigga bitch bitch bitch bitch hoe hoe hoe nigga [Juicy J] (background mixed through various parts of whole song) drop em in the trunk lock em in trunk real fast you'll be flying [Crunchy Black] we bout to ride on these fools cock these nines on these fools [x2] [DJ Paul] like thisssssssssss now in my city its so real in my city its so fake got some niggas that's gone play got some niggas that gone hate got some niggas that's gone dis the treal niggas on the tape but them the ones who want the streets so they start to evaporate that's why them niggas ain't around no more cause them niggas could sell no more without the Hypnotize or the Prophet nigga you is no more got plaques up on my walls got twenties on my cars keep coming like you coming and I'm gonna show you I ain't fucked up bout no charge nigga [Juicy J] can you niggas feel my pain catch me standing in the rain holding on a rusty 2 bout to act a fuckin fool is the 6 the devil though make you wanna powder your nose have you smoking hydro weed satisfaction guaranteed bucking wild and throwing signs knowing these niggas done loss they minds blame it on Coriddy and Ooh when we cock them thangs and shoot thinking somebody had seen my face now I'm gonna catch a murder case just gonna beat him round for round and leave him in -

Three 6 Mafia Most Known Unknown Mp3, Flac, Wma

Three 6 Mafia Most Known Unknown mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Most Known Unknown Country: US Released: 2006 Style: Gangsta MP3 version RAR size: 1630 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1361 mb WMA version RAR size: 1969 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 588 Other Formats: TTA AA AIFF ASF MIDI WAV AUD Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Most Known Unknown Hits Stay Fly 2 Featuring – Eightball & MJG*, Young Buck Roll WIth It 3 Featuring – Project Pat Don't Violate 4 Featuring – Frayser Boy Swervin' 5 Featuring – Mike Jones , Paul Wall Knock The Black Off Yo Ass 6 Featuring – Project Pat Poppin' My Collar 7 Featuring – Project Pat Hard Hittaz 8 Featuring – Boogiemane Side 2 Side 9 Featuring – Kanye West, Project Pat 10 Half On A Sack 11 Skit When I Pull Up At The Club 12 Featuring – Paul Wall Pussy Got Ya Hooked 13 Featuring – Remy Ma* Don't Cha Get Mad 14 Featuring – Lil' Flip Body Parts 3 15 Featuring – Boogiemane, Chrome , Crunchy Black, D.J. Paul*, Frayser Boy, Grandaddy Souf, Juicy "J"*, Lil' Wyte, Project Pat Hard Out Here For A Pimp 16 Featuring – Paula Campbell Stay Fly (Still Fly Remix) 17 Featuring – Project Pat, Slim Thug, Trick Daddy 18 Outro Bonus Tracks: Got It 4 Sale 19 Featuring – Chrome 20 Let's Plan A Robbery Side 2 Side 21 Featuring – Bow Wow, Project Pat 22 Ain't Got Time For Gamez Companies, etc. Pressed By – Sonopress Arvato, USA – F702501 Credits A&R – Dino G. DelVaille* Mastered By – James Cruz Producer, Executive-Producer, Recorded By, Mixed By, Programmed By – D.J. -

3 6 Mafia Side 2 Side Mp3 Download

3 6 mafia side 2 side mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Three 6 Mafia – Side 2 Side. Artist: Three 6 Mafia, Song: Side 2 Side, Duration: , File type: mp3. №renuzap.podarokideal.ru More popular Three 6 Mafia mp3 songs include: Stay Fly Lyrics, Side 2 Side Lyrics, Sippin On Some Syrup Lyrics, Poppin' My Collar Lyrics, Who Run It Lyrics, Skit Lyrics, Knock tha Black off Yo Ass Lyrics, Hard out Here for a Pimp Lyrics, When I Pull Up At the Club Lyrics, Pussy Got Ya Hooked Lyrics, Tongue Ring Lyrics, Ain't Got Time for Gamez renuzap.podarokideal.ru Stream Most Known Unknowns (Instrumentals) Mixtape by Three 6 Mafia. Most Known Unknowns (Instrumentals) Mixtape by Three 6 Mafia Three 6 Mafia ; ,; Stream. Download. Added: 06/07/ 58,; 10,; Rating Failed. Favorite; Share; Like; Dislike; Short URL: Embed Wide Player: - 09 - Side 2 Side. Three 6 Mafia (Instrumental renuzap.podarokideal.ru Three 6 Mafia, originally known as Backyard Posse and Triple 6 Mafia, is an incredibly influential hardcore rap group from Memphis, Tennessee. Started in by Juicy J, D.J. Paulrenuzap.podarokideal.ru The free three 6 mafia loops, samples and sounds listed here have been kindly uploaded by other users. If you use any of these three 6 mafia loops please leave your comments. Read the loops section of the help area and our terms and conditions for more information on how you can use the renuzap.podarokideal.ru://renuzap.podarokideal.ru Buy Three 6 Mafia Most Known Hits Mp3 Download.. Preview full album. ; Track title Duration Bitrate. -

Rap Vocality and the Construction of Identity

RAP VOCALITY AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF IDENTITY by Alyssa S. Woods A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Theory) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Nadine M. Hubbs, Chair Professor Marion A. Guck Professor Andrew W. Mead Assistant Professor Lori Brooks Assistant Professor Charles H. Garrett © Alyssa S. Woods __________________________________________ 2009 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people. I would like to thank my advisor, Nadine Hubbs, for guiding me through this process. Her support and mentorship has been invaluable. I would also like to thank my committee members; Charles Garrett, Lori Brooks, and particularly Marion Guck and Andrew Mead for supporting me throughout my entire doctoral degree. I would like to thank my colleagues at the University of Michigan for their friendship and encouragement, particularly Rene Daley, Daniel Stevens, Phil Duker, and Steve Reale. I would like to thank Lori Burns, Murray Dineen, Roxanne Prevost, and John Armstrong for their continued support throughout the years. I owe my sincerest gratitude to my friends who assisted with editorial comments: Karen Huang and Rajiv Bhola. I would also like to thank Lisa Miller for her assistance with musical examples. Thank you to my friends and family in Ottawa who have been a stronghold for me, both during my time in Michigan, as well as upon my return to Ottawa. And finally, I would like to thank my husband Rob for his patience, advice, and encouragement. I would not have completed this without you. -

1 University of Mississippi American Music Archives Field

University of Mississippi American Music Archives Field School Document Type: Tape Log of interview with Delmar “Mr. Del” Lawrence Field Worker: Cathryn Stout Coworker: Jonathan Dial Location: Business office of DMG record label. 8620 Trinity Road, Suite 206, Cordova, Tenn. Begin Date: Monday, May 17, 2010 End Date: Monday, May 17, 2010 Elapsed Time: 44 minutes and 10 seconds Notation: CS refers to Cathryn Stout, DL refers to Mr. Del and JD refers to Jonathan Dial. In 2000, Delmar “Mr. Del” Lawrence’s secular single “Ass and Titties” went gold and Mr. Del was a member of the Memphis rap group Three 6 Mafia. But shortly after that success, he had a conversion experience and dedicated his career to holy hip-hop music. I met Mr. Del at the office of his record label, Dedicated Music Group, to discuss his crossover from secular to Christian music, his background growing up in Memphis and his latest projects. 00:50 DL says that he was born in the Whitehaven neighborhood of Memphis, Tenn. and later moved to Cordova. He says that he never had a relationship with his father, but his mother was an entrepreneur who owned a daycare, a hair salon and real estate. He has a younger brother and two older sisters and describes himself as “the only musical person” in his family. 01:50 DL recalls beating on pots and pans as a child and calls himself a born drummer. He later studied percussion in school. He also grew up writing poetry and says that he got introduced to hip-hop music at the age of 7.