Oral History Interview with Eli Broad, 2012 Jan. 30-April 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leonard Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts

LEONARD FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC BERNSTEIN FESTIVAL OF APRIL 7-14, 2019 THE CREATIVE ARTS The Festival of the Creative Arts was founded in 1952 by the brilliant composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein. Each spring, Brandeis cele- brates the abundant creativity of its students, faculty, staff and alumni, joined by professional artists from around the country. Festival events are free and open to the public unless otherwise noted. For schedule updates, visit brandeis.edu/arts/festival. LEONARD BERNSTEIN Leonard Bernstein (1918-90) was one of the great American he conducted concerts on both sides of the wall. In the early artists of the 20th century. A composer, conductor, pianist, days of AIDS research, Bernstein raised the first million dol- teacher, thinker and adventurous spirit, he transformed the lars for a community-based clinical trials program run by the way we hear music and experience the arts. American Foundation for AIDS Research. Bernstein’s successes ranged from the Broadway stage Bernstein was a member of the Brandeis music department (“West Side Story,” “Candide,” “On the Town”) to television faculty from 1951-56. He received an honorary doctorate from and film, to international concert halls. His major concert Brandeis in 1959 and served as a University Fellow from 1958- works, including the symphony “Kaddish” and the choral 76 and on the university’s board of trustees from 1976-81. He works “Mass” and “Chichester Psalms,” are studied and was a trustee emeritus until his death in 1990. performed around the world. He was a dynamic leader of the world’s greatest orchestras, including the New York For the university’s first commencement, in 1952, Bernstein Philharmonic (1958-69). -

Michigan State University Eli Broad Graduate School of Management

Michigan State University Eli Broad Graduate School of Management *The information provided in this profile has been written using public information on the Michigan State University, Eli Broad Graduate School of Management, and was not created by Michigan State University for specific use in this publication. RECRUITMENT AND SCHOLARSHIPS/FELLOWSHIPS What programs and initiatives has your school found successful in the recruitment of minority and/or female students? The Michigan State MBA program makes a special effort to recruit talented potential managers from historically underrepresented groups—African- American, Latino(a)/Chicano(a), Asian/Pacific Islander and Native American (ALANA). It does so through a variety of programs and events both on and off campus, including: Multicultural Business Program (MBP) The purpose of the Multicultural Business Program is to improve the recruitment, retention and graduation rate of multicultural students by providing opportunities for them to develop full academic and career potentials. Its programs promote a success philosophy by fostering a positive awareness of personality, gender, physical and cultural differences. The MBP office works with students to identify individual strengths, values, interests and goals. Women in Business Conference The Women in Business Conference, held annually, is co-sponsored by the MBA program’s Graduate Women in Business student association. During the evening conference, we hope to give prospective female MBAs insight into the many career and growth opportunities available after graduate school. Activities include a panel of current women MBA students and recent Broad MBA alumni sharing why they decided to leave the work force to pursue an MBA full time. In addition, they will also address a variety of issues including how to balance their work, school and family priorities; tips for being successful in school and on the job; the benefit of networking with other women; and career opportunities for newly minted MBA graduates. -

Summary Vita Of

Curriculum Vita of SANJAY GUPTA The Eli & Edythe L. Broad Dean Eli Broad College of Business, Michigan State University N520 Business College Complex, 632 Bogue Street, East Lansing, Michigan 48824-1122 Email: [email protected]; Tel: 517-355-8377; Fax: 517-353-6395 December 2019 Sanjay Gupta is the Eli & Edythe L. Broad Dean, the 11th dean of the Eli Broad College of Business at Michigan State University. Prior to his current role, he was the Russell Palmer Endowed Professor in Accounting and held positions as the Acting Dean, the Associate Dean for MBA and Professional Masters programs, and Chairperson of the Accounting and Information Systems Department in the Broad College. Prior to returning to MSU in 2007, he received tenure and held several positions in the W. P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University over a 17-year period, including the first Henry & Horne Professorship in Accountancy, Dean’s Council of 100 Distinguished Scholar, and Faculty Director of the Master of Accountancy & Information Systems and the Masters of Taxation programs. Professor Gupta was selected by the Broad College’s Executive MBA Class of 2010 for the Faculty Excellence Award awarded to one faculty each year, and by the Arizona Society of CPAs with the Accounting Education Innovation Award and the Outstanding Educator Award for significant contributions to curricular and co-curricular innovation and development. He was chosen by MSU for the Committee on Institutional Cooperation’s (CIC) Academic Leaders Program and the CIC’s Department Executive Officers’ Seminar. Professor Gupta’s research focuses on corporate and individual tax policy issues. -

Rose Art Museum's Sam Hunter Emerging Artists Fund Committee

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Nina J. Berger, [email protected] 617.543.1595 High-resolution images available on request ROSE ART MUSEUM’S SAM HUNTER EMERGING ARTISTS FUND COMMITTEE SELECTS TWO WORKS BY B. INGRID OLSON TO ENTER THE COLLECTION (Waltham, MA) –The Rose Art Museum has announced that work by B. Ingrid Olson has been selected for acquisition by the Sam Hunter Emerging Artists Acquisition Fund Committee. Inspired by the legacy of the Rose’s founding director, Sam Hunter, the fund is generated annually and administered by a committee that aims to collect the work of promising artists on the cusp of recognition. Two works by Chicago-based Olson–Arched fold, bent of another movement, 2017 and Firing distance, scission, 2017–have been acquired for the Rose Art Museum’s collection. Straddling sculpture and photography, Olson’s work plays fascinating games with perception and vision. Olson was recently featured in a two-person exhibition at The Renaissance Society in Chicago, and her first solo museum show will open at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in March 2018. Her work will also be included in Being: New Photography 2018, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (March 2018) and in a group show at the MCA Chicago, Picture Fiction: Kenneth Josephson and Contemporary Photography (April 28– December 30, 2018). “Ingrid is an extraordinary photographer, pushing the bounds of the medium while engaging with pressing issues of gender identity and representation,” say Leslie Aronzon, a member of this year’s committee. “Her work fits in well with the Rose collection, and we are so excited to add her impressive and fresh works to our permanent collection.” Joining Aronzon on this year’s committee are Kim Allen-Niesen, Steven Bunson, Tory Fair, Betsy Pfau, and Lisa Wyett. -

Framework for the Future

THE FRAMEWORK FOR THE FUTURE FINAL REPORT January 2020 The Framework for the Future: Prefatory Remarks Brandeis University is at an important crossroads in its 72-year history. Founded by the American Jewish community on the principles of academic excellence and openness in hiring and admissions practices, Brandeis has achieved an inspiring degree of success — not just as a young university committed to educating undergraduates in the liberal arts but also as a major research institution. The Framework for the Future provides a scaffolding for the university’s coming decades. It is rooted in the institution’s history and builds upon its unique place in higher education. The Framework is the synthesis of more than three years of broad consultations with focus groups, including prospective students, current students, alumni, faculty, staff, trustees, friends, and parents. It is also based on responses from multiple alumni surveys; information gleaned from 30 “self-reflection” documents written by faculty and administrators; and the work of four task forces, composed of 11 working groups, which forwarded for consideration more than 250 recommendations. The synthesis of these sources does not include many of the recommendations that came out of the task force reports. Rather, it offers some overarching themes that require our attention most urgently as we seek to plan and advance Brandeis’ future. And while the Framework provides guideposts within which we will pursue many initiatives, its purpose is not to identify all the university’s plans, strengths, and achievements. Instead, it outlines a series of strategic initiatives and investments, especially in areas where we have over the years underinvested, which will allow us to build a stronger Brandeis over the next several years. -

To Download a PDF of an Interview with Eli Broad, Founder, the Broad

Building a Broad Legacy An Interview with Eli Broad, Founder, The Broad Foundations EDITORS’ NOTE After working for arts, what made you decide to When you had the vision for the museum, two years as an accountant, Eli focus on those areas, and are they could you have anticipated this type of Broad founded a home-building interrelated? reception? company with Donald Kaufman. In They are separate focuses, but there No. The attendance is almost three times what 1971, the Kaufman and Broad Home is some relationship among them. we expected, and we have in a way reinvented the Corporation acquired a small life In terms of scientific and medi- American museum. insurance company for $52.1 million cal research, the Broad Institute partners It is very friendly. The building is by Diller that Broad eventually transformed with Harvard and MIT, and it’s our Scofidio + Renfro, who did the High Line New into a retirement savings empire. biggest investment – $700 million and York, re-did Lincoln Center, and are doing an addi- With the merger of SunAmerica into it’s 14 years old; it has 2,500 people and tion to MOMA. It’s a very innovative building. AIG in 1999, Broad stepped down as a $450 million annual research budget. We also don’t have security guards – we have CEO and turned his full-time attention They’ve done wonders there. It’s number visitor service associates. These are young people to philanthropy. Broad is the found- Eli Broad one in the world now in genomics, so we who we give 50 hours of training to, and while ing Chairman and Life Trustee of The feel good about that, and that will be a they ensure the art is protected, they engage the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and great part of our legacy. -

Lisa Russell CV 2018

Lisa Russell EDUCATION MFA School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Tufts University, Boston MA BFA Massachusetts College of Art, Boston MA SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2018 Here and Now, Dolby Chadwick Gallery, San Francisco, CA Nature, Attleboro Museum, Attleboro MA Still-life: Captured Moments, University Place Gallery, Cambridge MA 2018 Exhibition, Artist of the Year Award, University Place Gallery, Cambridge MA 5th Monotype/Monoprint, Art Complex Museum, Duxbury MA CAA Fall Salon, Katheryn Schultz Gallery, Cambridge MA Pressing Matters, Monotype Guild, Lynn Arts, MA 2017 Catamount Film and Arts, Arts Connect Catamount Arts, Johnsbury, VT Juror: Andrea Rosen, Curator Fleming Museum of Art, Burlington, VT Flower, Attleboro Museum, Attleboro, MA Small Wonders, Monotype Guild of New England , Hopkinton Center for the Art, Hopkinton, MA 2-D Works, Bannister Gallery, Rhode Island College, Providence RI Mary Schein Fall Salon , Kathryn Schultz Gallery, Cambridge MA Salon Des Refuses, Galleries at Kimball Jenkins Estate, Concord, NH 2016 Painterly Interplay: Perception and Reality, Kathryn Schultz Gallery, Cambridge, MA Lisa Russell, Edwina Rissland, Roz Sommer Blue, University Place Gallery, Cambridge MA Fourth, Monotype Guild of NENG, Attleboro Museum, Attleboro, MA Winter Break, University Place Gallery, Cambridge, MA Salon, Kathryn Schultz Gallery, Cambridge, MA Red Biennial, CAA, Cambridge, MA 2015 14th National Kathryn Schultz Gallery, Cambridge, MA Juror: Caitilin Doherty, Curator and Deputy Director Curatorial Affairs, Eli & Edythe Broad Art Museum, -

The Rose Art Museum

The Rose Art Museum “The Rose at Brandeis: Works from the Collection” Curated by Adelina Jedrzejczak and Roy Dawes Oct. 28, 2009 – May 23, 2010 The Rose Art Museum Brandeis University Fall exhibition, special catalogue will mark celebration of The Rose Art Museum’s permanent collection WALTHAM, Mass.— In fall 2009, The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University will feature its renowned collection, which includes modern and contemporary masterworks by some of the 20th century’s most revered artists, in an historic exhibition and catalogue. The wide-ranging show entitled, “The Rose at Brandeis: Works from the Collection” opens on Oct. 28th and will present the breadth of the collection by including pieces from dozens of artists who represent different historical periods, from Willem de Kooning, to Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Morris Louis, Andy Warhol, Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler, Max Weber, Cindy Sherman, Kiki Smith, Larry Rivers, Philip Guston, Frank Stella, Jennifer Bartlett, Hans Hoffman, Louise Nevelson and Elsworth Kelley, among others. The exhibition will also explore the depth of The Rose’s holdings by focusing on groupings of artworks by several artists, to expose both artistic development and the process of collecting. “The length of the exhibition, running from October through May 23, 2010, will allow students and the public unprecedented access to some of the key artworks in the collection,” said show co-curator and Director of Museum Operations Roy Dawes. “It will allow museum visitors time to properly see, contemplate, study, revisit and gain perspective on this stupendous collection.” “The Rose at Brandeis” coincides with the Oct.1 publication of the first comprehensive catalogue of the museum’s collection. -

Every Rose Has Its Thorn: a New Approach to Deaccession Andrew W

Hastings Business Law Journal Volume 6 Article 4 Number 2 Summer 2010 Summer 1-1-2010 Every Rose Has Its Thorn: A New Approach to Deaccession Andrew W. Eklund Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_business_law_journal Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew W. Eklund, Every Rose Has Its Thorn: A New Approach to Deaccession, 6 Hastings Bus. L.J. 467 (2010). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_business_law_journal/vol6/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Business Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVERY ROSE HAS ITS THORN: A NEW APPROACH TO DEACCESSION Andrew W. Eklund* INTRODUCTION In 1961, Edgar and Bertha Rose donated $1 million to Brandeis University to form the Rose Art Museum ("the Rose").' Initially, the Rose had no acquisition budget, so the now-7000-piece collection was built on gifts.2 Focused on twentieth-century art, the collection includes a strong selection of post-war artists like Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Roy Lichtenstein,3 many of which were acquired through the initial gifts to the museum.4 In the face of the financial crisis and reduced donations due to the Bernard Madoff scandal, Brandeis University's board of trustees voted unanimously to close the Rose and sell the entire collection on January 26, 2009.5 Valued at approximately $350 million, the Rose was targeted to help deal with Brandeis' budget deficit, alleged to be as much as $10 million,6 as well as a decline in the University's endowment, from $712 million to $549 million, or twenty-three percent, since the financial crisis began. -

Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and the Broad Art Founda- Tion, Have Assets of $2.7 Billion

ELI BROAD is a renowned business Eli and leader who built two Fortune 500 companies Edythe from the ground up over a five-decade Broad career in business. He is the founder-chairman Founders of of both SunAmerica Inc. and KB Home (formerly Kaufman and Broad Home The Broad Foundations Corporation). Founding partners Today, Eli Broad and his wife, Edythe, are devoted to philanthropy as founders of the Broad Institute of The Broad Foundations, which they established to advance entrepreneurship of MIT and Harvard for the public good in education, science, and the arts. The Broad Foundations, which include The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and The Broad Art Founda- tion, have assets of $2.7 billion. The Broads’ investments in scientific and medical research are focused on three areas: human genomics, stem cell research, and inflammatory bowel disease. In an unprecedented partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technol- ogy, Harvard University, and the Whitehead Institute, the Broads in June 2003 announced the $100 million founding gift to create The Eli and Edythe Broad Institute for biomedical research. The institute’s aim is to realize the promise of the human genome to revolutionize clinical medicine and to make knowledge freely available to scientists around the world. They gave a second $100 million gift to the Broad Institute in 2005, and in 2008, with the Broad Institute firmly established as the world’s leading genomics and biomedical research institute, they gave $400 million to create an endowment that will make the institute permanent. In 2013, they gave another $100 million, bringing their total investment in the Broad Institute to $800 million. -

Bcam at Lacma

BCAM AT LACMA The Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM), opening February 16, 2008, is the centerpiece of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s (LACMA) Transformation—an ambitious program of expansion and renovation. Designed by Renzo Piano, founder, Renzo Piano Building Workshop, BCAM has been made possible thanks to a $60 million donation from Eli and Edythe Broad, including $50 million to the museum’s capital campaign and a pledge to cover the cost of the building over $50 million. The remaining $10 million was donated to fund acquisitions and was used in part in 2007 to purchase Richard Serra’s monumental sculpture Band (2006). Mr. Broad is a longtime LACMA Trustee, and he and Mrs. Broad are among the world’s most generous philanthropists, with interests that include the arts, education, and science. The three-story BCAM includes 60,000 square feet of exhibition space—one of the largest column-free art spaces in the United States— designed specifically for The Broad Contemporary Art Museum at LACMA the display of contemporary art. Included in the initial installation are some 160 works from the renowned collection of The Broad Art Foundation and the Broads’ personal collection, as well as forty works from LACMA’s own holdings in contemporary art and from other lenders. LACMA Director Michael Govan states, “The creation of BCAM greatly expands LACMA’s contemporary art program, both enriching the experience of its historical collections and placing LACMA in a position of prominence in the area of contemporary art among encyclopedic museums. We are additionally pleased that BCAM will enable us to show the work of several key artists in great depth, providing an exceptionally rewarding experience for visitors. -

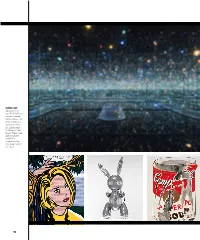

On the Scene at Coachella 2016 ICONIC ART (Clockwise from Top

ICONIC ART (Clockwise from top) You’ll find Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrored Room - The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away,” Roy Lichtenstein’s “I...I’m Sorry!,” Jeff Koons’ “Rabbit” and Andy Warhold’s “Small Torn Campbell’s Soup Can (Pepper Pot) at The Broad. Mark On the scene at Coachella 2016 98 Making a THESE FOUR GREAT SHAPERS EXPLAIN HOW THEY ARE PROGRESSING THE ART SCENE IN LOS ANGELES, THE CITY OF CONTINUOUS YOUTH AND ADAPTATION MaBY MARINE TANGUY rk There is no question that the current art world is evolving. From the rise of startups challenging the existing gallery model to a possible regulation of the market, we are entering a new era in the field. As always, with change, there are those who embrace it and those who fear it. But while the renowned art scenes of London and New York struggle to break their tradition and pre-establishment, L.A. is stepping up and becoming a lab for innovation and experimentation. Here’s to the bold and the visionaries—we have a lot to learn from them. PHOTOS COURTESY OF YAYOI KUSAMA/DAVID ZWIRNER, ROY LICHTENSTEIN/ ZWIRNER, ROY KUSAMA/DAVID OF YAYOI COURTESY PHOTOS STUDIO AND M. PARKER JEFF KOONS/DOUGLAS STUDIO, DOUGLAS M. PARKER INC./ ARTS, THE VISUAL FOR FOUNDATION WARHOL ANDY WARHOL/THE ANDY CAMPBELL TRADEMARKS USED WITH PERMISSION OF ARIST RIGHTS SOCIETY, CAMPBELL SOUP COMPANY 99 THE LOS ANGELES ART COLLECTORS ing ones, Edythe responds, “We have a long cessible to the public, so we decided to build ELI AND EDYTHE BROAD history of supporting public museums—Eli The Broad, endow it, fill it with our collection The Broads have about 2,000 works in was the founding chairman of MOCA and a and offer free general admission as a gift to their collection, one of the most prominent life trustee of MOCA, LACMA, MOMA.