University of Birmingham "Like a Dog": Remaking the Irish Law Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

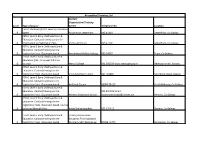

Accredited Training List Contact Organisation/Training Level Type of Course Centre Telephone No

Accredited Training List Contact Organisation/Training Level Type of Course Centre Telephone No. Location FETAC Childcare (NCVA Level 5) Classroom 5 based Youthreach Letterfrack 095 41893 Letterfrack, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre for 5 information on registration fees. VTOS Letterfrack 095 41302 Letterfrack, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Archbishop McHale College 093 24237 Tuam, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education (PLC - One year full time 5 course) Mercy College 091 566595 www.mercygalway.ie Newtownsmith, Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. VTOS Merchants Road 091 566885 Merchants Road, Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Ard Scoil Chuain 09096 78127 Castleblakeney, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 091 844159 Email: 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Athenry Vocational School [email protected] Athenry, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - registration fees. Classroom based. Course 5 delivered through Irish. Ionad Breisoideachais 091 574411 Rosmuc, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Galway Roscommon Education. Contact training centre - Education Training Board 5 registration fees. Classroom based. (formerly VEC) Ballinasloe 09096 43479 Ballinasloe, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Galway Roscommon Education. Contact training centre - Education Training Board 5 registration fees. Classroom based. (formerly VEC) Oughterard 091 866912 Oughterard, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. -

Crystal Reports

Bonneagar Iompair Éireann Transport Infrastructure Ireland 2020 National Roads Allocations Galway County Council Total of All Allocations: €28,848,266 Improvement National Primary Route Name Allocation 2020 HD15 and HD17 Minor Works 17 N17GY_098 Claretuam, Tuam 5,000 Total National Primary - HD15 and HD17 Minor Works: €5,000 Major Scheme 6 Galway City By-Pass 2,000,000 Total National Primary - Major Scheme: €2,000,000 Minor Works 17 N17 Milltown to Gortnagunnad Realignment (Minor 2016) 600,000 Total National Primary - Minor Works: €600,000 National Secondary Route Name Allocation 2020 HD15 and HD17 Minor Works 59 N59GY_295 Kentfield 100,000 63 N63GY RSI Implementation 100,000 65 N65GY RSI Implementation 50,000 67 N67GY RSI Implementation 50,000 83 N83GY RSI Implementation 50,000 83 N83GY_010 Carrowmunnigh Road Widening 650,000 84 N84GY RSI Implementation 50,000 Total National Secondary - HD15 and HD17 Minor Works: €1,050,000 Major Scheme 59 Clifden to Oughterard 1,000,000 59 Moycullen Bypass 1,000,000 Total National Secondary - Major Scheme: €2,000,000 Minor Works 59 N59 Maam Cross to Bunnakill 10,000,000 59 N59 West of Letterfrack Widening (Minor 2016) 1,300,000 63 N63 Abbeyknockmoy to Annagh (Part of Gort/Tuam Residual Network) 600,000 63 N63 Liss to Abbey Realignment (Minor 2016) 250,000 65 N65 Kilmeen Cross 50,000 67 Ballinderreen to Kinvara Realignment Phase 2 4,000,000 84 Luimnagh Realignment Scheme 50,000 84 N84 Galway to Curraghmore 50,000 Total National Secondary - Minor Works: €16,300,000 Pavement HD28 NS Pavement Renewals 2020 -

FORUM Connemara CLG End of Year Report 2018

FORUM Connemara CLG End of Year Report 2018 1 FORUM CONNEMARA CLG END OF YEAR REPORT January –December 2018. Introduction From January December 2018, Forum staff implemented actions under a number of programmes; The Rural Development Programme (Leader), The Adolescent Support Programme, the Rural Recreation Programme (RRP), the Rural Social Scheme, and Labour Activation Programmes Tus, Job Initiative, and Community Employment. There were difficulties in filling Tus places and in April the Department proposed a cutback to our allocation from 80 to 40 places. Forum meet with the Department in October .The Department confirmed our allocation of 40 places on Tus and 36 on RSS .The company lost two TUS supervisors but gained an additional supervisor for the RSS programme. Forum were allocated an additional 12 places on the RSS programme. These places are filling slowly, There are currently 31 places filled with 5 places remaining to be filled .. There will be a further review of places on both schemes scheme at the end of April 2019. During the year various staff gave comprehensive presentations on their work to the Board of Directors. This included work undertaken by the Rural Recreation Officer and the Adolescent Support Coordinator. The Adolescent Support Programme had a very successful 20th birthday celebration in May and there was also a presentation of the programmes activities to the GRETB Board who part fund the programme. The company’s finances are in a healthy state as at the end of December . Minister Ring’s Mediator/Facilitator: Representatives from Forum meet with Tom Barry facilitator on Wednesday 28th March 2018. -

Thatchers in Ireland (21.07.2016)

Thatchers in Ireland (21.07.2016) Name Address Telephone E-mail/Web Gerry Agnew 23 Drumrammer Road, 028 2587 82 41 Aghoghill, County Antrim, BT42 2RD Gavin Ball Kilbarron Thatching Company, 061 924 265 Kilbarron, Feakle, County Clare Susanne Bojkovsky The Cottage, 086 279 91 09 Carrowmore, County Sligo John & Christopher Brereton Brereton Family Thatchers, 045 860 303 Moods, Robertstown, County Kildare Liam Broderick 12 Woodview, 024 954 50 Killeagh, County Cork Brondak Thatchers Suncroft, 087 294 45 22 Curragh, 087 985 21 72 County Kildare 045 860 303 Peter Brugge Master Thatchers (North) Limited, 00 44 (0) 161 941 19 86 [email protected] 5 Pines Park, www.thatching.net Lurgan, Craigavon, BT66 7BP Jim Burke Ballysheehan, Carne, Broadway, County Wexford Brian Byrne 6 McNally Park, 028 8467 04 79 Castlederg, County Tyrone, BT81 7UW Peter Childs 27 Ardara Wood, 087 286 36 02 Tullyallen, Drogheda, County Louth Gay Clarke Cuckoo's Nest, Barna, County Galway Ernie Clyde Clyde & Reilly, 028 7772 21 66 The Hermitage, Roemill Road, Limavady, County Derry Stephen Coady Irish Master Thatchers Limited, 01 849 42 52 64 Shenick Road, Skerries, County Dublin Murty Coinyn Derrin Park, Enniskillen, County Fermanagh John Conlin Mucknagh, 090 285 784 Glassan, Athlone, County Westmeath Seamus Conroy Clonaslee, 0502 481 56 County Laois Simon Cracknell; Cool Mountain Thatchers, 086 349 05 91 Michael Curtis Cool Mountain West, Dunmanaway, County Cork Craigmor Thatching Services Tullyavin, 086 393 93 60 Redcastle, County Donegal John Cunningham Carrick, -

(M3/Day) Type of Treatment Galway County

Volume Supplied Organisation Name Scheme Code Scheme Name Supply Type Population Served (m3/day) Type Of Treatment Occassional pre-chlorination to remove iron and manganese, rapid Galway County Council 1200PUB1001 Ahascragh PWS PWS 810 859 gravity filters, UV and chlorination with sodium hypochlorite. Dosing with aluminium sulphate and polyelectrolyte, clarification, Galway County Council 1200PUB1004 Ballinasloe Public Supply PWS 8525 3995 pressure filtration, chlorination with Chlorine gas Pressure filters containing granular activated carbon media, UV, Galway County Council 1200PUB1005 Ballyconneely PWS PWS 133 511 chlorination with sodium hypochlorite solution Pre-chlorination as required to removed iron and manganese; rapid gravity filter with silica sand and manganese dioxide, duty/standby UV Galway County Council 1200PUB1006 Ballygar PWS PWS 1037 316 and chlorination with sodium hydroxide Pre-chlorination with sodium hypochlorite and sodium hydroxide as required to remove iron and manganese; Rapid gravity filter with silica sand and manganese dioxide; duty/standby UV and chlorination with Galway County Council 1200PUB1007 Ballymoe PWS PWS 706 438 sodium hydroxide. Chemical clarification, ph correction, coagulation, floculation, Galway County Council 1200PUB1008 Carna/Kilkieran RWSS PWS 2617 1711 settlement tanks, rapid gravity filters, post chlorination Galway County Council 1200PUB1009 Carraroe PWS PWS 3414 1766 Chlorination Galway County Council 1200PUB1011 Cleggan/Claddaghduff PWS 565 162 chemical coagulation, filtration, UV -

Galway County Development Board - Priority Actions 2009-2012

Galway CDB Strategy 2009-2012, May 2009 Galway County Development Board - Priority Actions 2009-2012 Table of Contents Galway County Development Board ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Priority Actions 2009-2012.............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Galway County Development Board........................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Format of Report.............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Section 1: Priority Strategy - Summary....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Section 2 - Detailed Action Programme..................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Tracing Your Roots in North-West Connemara

Tracing eour Roots in NORTHWEST CONNEMARA Compiled by Steven Nee This project is supported by The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development - Europe investing in rural areas. C O N T E N T S Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... Page 4 Initial Research (Where to begin) ............................................................................................................... Page 5 Administrative Divisions ............................................................................................................................... Page 6 Useful Resources Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. Page 8 Census 1901/1911 ......................................................................................................................................... Page 8 Civil/State Records .................................................................................................................................... Page 10 National Repositories ................................................................................................................................. Page 10 Griffiths Valuation ........................................................................................................................................ Page 14 Church Records ......................................................................................................................................... -

MAPPED a Study of Planned Irish Villages.Pdf

m a p p d m a p p d 1 m a p p d m a p p d m a p p d 2 3 m a p p d a study of planned irish villages 4 5 Published by Dublin School of Architecture Dublin Institute of Technology (DIT) Dublin June 2017 ISBN No. 978-0-9932912-4-1 Editor: Miriam Delaney Contact: [email protected] Dublin School of Architecture DIT Produced by: Cian Burke, Dimitri Cusnir, Jason Ladrigan, David McCarthy Cillian McGrath, Michael Weir With Support from: © Dublin School of Architecture Press All rights reserved All information presented in this publications deemed to be the copyright of the Dublin School of Architecture creator of the Dublin School of Architecture, unless stated otherwise. Fair Dealing Notice: This Publication contains some copyrighted material whose use has not been authorised by the copyright owner. We believe that this non-for-profit, educational publication constitutes a fair dealing of the copyrighted material. Lagan Cement Printed by Anglo Printers, Drogheda, Ireland dublin school of architecture press All our generous sponsors on ‘Fundit’ from 2015- 2017 6 Contents: 7 9 ........................................... Acknowledgements 11 ........................................... Introduction 12 ........................................... Mountbellew ............................................. Non-Conformity-The Bellew Family ............................................. Cillian McGrath 98 .......................................... Portlaw ..................................................... The Portlaw Roof Truss: A Historic and Architectural -

1. Major Samuel Perry, Formerly of Moycullen House, Had a Sister Who

Moycullen Local History Quiz Number Thirteen– Answers We hope you enjoyed this quiz. 1. Major Samuel Perry, formerly of Moycullen House, had a sister who was the first woman in Europe to do what? Answer: In 1906, from Queen’s College Galway (now NUIG), Alice Jacqueline Perry (1885-1969) became the first woman in Europe to graduate with a degree in Engineering (first class honours degree in Civil Engineering). Following her father James’ death the same year, she succeeded him temporarily as County Surveyor for Galway County Council - a post he had held since before her birth. Alice was an unsuccessful candidate when the permanent appointment was made. She still remains the only woman to have served as a County Surveyor (County Engineer) in Ireland. She died in Boston, USA, where she had been working within the Christian Science movement as a poetry editor and practitioner. In 2017 NUIG named their Engineering building in her honour. (Major Samuel Perry [1879-1945] was the only brother of Alice and her four sisters, Molly, Nettie, Agnes and Martha) 2. Where in Moycullen would you find Hangman’s Hill? Answer: The hill just behind Tullokyne school, along the esker road, is known as Cnoch an Crocadóir or Hangman’s Hill or also as Cnochán an Chrochta, the Hill of the Hanging. Local lore refers to a soldier being hung on the site. 3. David Davies OBE, retired BBC TV host and former Executive Director of the English Football Association (FA) had a Moycullen born mother, what was her name? Answer: Margaret (Madge) Morrison (1913-1999), born on the Kylebroughlan corner of the village crossroads. -

Kate Aughey 2014

THE ZIBBY GARNETT TRAVELLING FELLOWSHIP Report by Kate Aughey Furniture Conservation At Conservation Letterfrack, Ireland 05 April – 19 April, 2014 1 Table of Contents Introduction: …………………………………………………………………3 Study Trip………………………………………………………………………4 Financial Costs………………………………………………………………....5 Report: Destination…………………………………………………………………….6 Surrounding Area………………………………………………………….…..7 Conservation Letterfrack……………………………………………………10 The Project…………………………………………………………………...10 Conclusions…………………………………………………………………14 Appendix 1: Treatment report for conservation work undertaken during placement. 2 Introduction Name: Kate Joanne Aughey Date of Birth: 10-02-1984 Age: 30 Nationality: British I am a Postgraduate student currently in my second and final year at West Dean College, West Sussex, where I study the Conservation of Furniture and Related Objects. I am also working towards a Master’s degree in Conservation Studies, which I hope to complete in the summer of 2015. At present, the scope of my study in the furniture department at West Dean is very general with all areas in the treatment of historic furniture undertaken. This includes working with metal ware such as locks and castors and decorative surfaces such as gilding. Upon completion of the Postgraduate Diploma, in July 2014, I plan to seek work in a larger scale furniture conservation / restoration workshop in or around London. It is my hope that by working alongside established practitioners, dealing with a wide range of furniture, I can continue to build on the training I have received at West Dean. The treatment of decorative elements such as carving and marquetry are particular interests of mine and so I intend to pursue these areas and perhaps specialize in the future. I recently completed work on one of a pair of 18th Century Italian gilt pier tables for The Wallace Collection, London. -

Mass Grave at Irish Orphanage May Hold 800 Children's Remains

Mass grave at Irish orphanage may hold 800 children's remains SHAWN POGATCHNIK Associated Press Seattle Times 4 June 2014 Anyone looking for more information or to donate to the fund can contact Corless via email: [email protected] DUBLIN. The Catholic Church in Ireland is facing fresh accusations of child neglect after a researcher found records for 796 young children believed to be buried in a mass grave beside a former orphanage for the children of unwed mothers. The Catholic Church in Ireland is facing fresh accusations of child neglect after a researcher found records for 796 young children believed to be buried in a mass grave beside a former orphanage for the children of unwed mothers. The researcher, Catherine Corless, says her discovery of child death records at the Catholic nun-run home in Tuam, County Galway, suggests that a former septic tank filled with bones is the final resting place for most, if not all, of the children. Church leaders in Galway, western Ireland, said they had no idea so many children who died at the orphanage had been buried there, and said they would support local efforts to mark the spot with a plaque listing all 796 children. County Galway death records showed that the children, mostly babies and toddlers, died often of sickness or disease in the orphanage during the 35 years it operated from 1926 to 1961. The building, which had previously been a workhouse for homeless adults, was torn down decades ago to make way for new houses. A 1944 government inspection recorded evidence of malnutrition among some of the 271 children then living in the Tuam orphanage alongside 61 unwed mothers. -

Report of the Inter-Departmental Group on Mother and Baby Homes

Report of the Inter-Departmental Group on Mother and Baby Homes Department of Children and Youth Affairs July 2014 I. Introduction The Inter Departmental Group was set up in response to revelations and public controversy regarding conditions in Mother and Baby Homes. This controversy originally centred on the high rate of deaths at the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Co. Galway. A local historian, Ms Catherine Corless, sourced details from public records of 796 child deaths, very many of them infants, in this home in the period from 1925 to 1961. There was also considerable anxiety and questions as to the burial arrangements for these infants. Notwithstanding that Tuam was the original focus of this controversy, related issues of death rates, burial arrangements and general conditions have also been raised with regard to Mother and Baby Homes in other locations. Shortly after the Inter-Departmental Group was established, Dáil Eireann passed a motion, following a Government sponsored amendment, on 11th June 2014 as follows: “That Dáil Éireann: acknowledges the need to establish the facts regarding the deaths of almost 800 children at the Bon Secours Sisters institution in Tuam, County Galway between 1925 and 1961, including arrangements for the burial of these children; acknowledges that there is also a need to examine other "mother and baby homes" operational in the State in that era; recognises the plight of the mothers and children who were in these homes as a consequence of the failure of religious institutions, the State,