MAPPED a Study of Planned Irish Villages.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

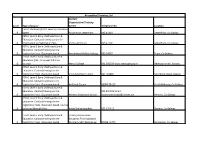

Accredited Training List Contact Organisation/Training Level Type of Course Centre Telephone No

Accredited Training List Contact Organisation/Training Level Type of Course Centre Telephone No. Location FETAC Childcare (NCVA Level 5) Classroom 5 based Youthreach Letterfrack 095 41893 Letterfrack, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre for 5 information on registration fees. VTOS Letterfrack 095 41302 Letterfrack, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Archbishop McHale College 093 24237 Tuam, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education (PLC - One year full time 5 course) Mercy College 091 566595 www.mercygalway.ie Newtownsmith, Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. VTOS Merchants Road 091 566885 Merchants Road, Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Ard Scoil Chuain 09096 78127 Castleblakeney, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - 091 844159 Email: 5 registration fees. Classroom based. Athenry Vocational School [email protected] Athenry, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. Contact training centre - registration fees. Classroom based. Course 5 delivered through Irish. Ionad Breisoideachais 091 574411 Rosmuc, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Galway Roscommon Education. Contact training centre - Education Training Board 5 registration fees. Classroom based. (formerly VEC) Ballinasloe 09096 43479 Ballinasloe, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Galway Roscommon Education. Contact training centre - Education Training Board 5 registration fees. Classroom based. (formerly VEC) Oughterard 091 866912 Oughterard, Co Galway FETAC Level 5 Early Childhood Care & Education. -

Irland 2014-Druck-Ii.Pdf

F. Higer: Nachlese der Pfarr-Reise 2014 auf die „Grüne Insel“ - - Inhalt 46 Connemara-Fotos 78 Land der Schafe 47 Lough Corrib 79 Killarney 3 Reiseprogramm 48 Croagh Patrick 80 Lady´s View 4 Irland 50 Westport 82 Adare 17 Irland - Geografie 51 Connemara 85 Rock of Cashel 21 Pale 52 Kylemore Abbey 89 Wicklow Montains 22 Röm.-kath. Kirche 56 Burren 91 Glendalough 24 Keltenkreuz 58 Polnabroune Dolmen 94 Dublin 25 Leprechaun / 60 Cliffs of Moher 100 St. Patrick´s Cathedral Rundturm 62 Limerick 103 Phoenix Park 26 Shamrock (Klee) 64 Augustiner / Limerick 104 Guinness Storehause 27 Flughafen Dublin 65 Tralee 106 St. Andrew´s Parish 28 Aer Lingus 66 Muckross Friary 107 Trinity College 31 Hotel Dublin 68 Muckross House 108 Trinity Bibliothek 32 Monasterboice 71 Star Seafood Ltd. 109 Book of Kells 34 Kilbeggan-Destillerie 72 Kenmare 111 Temple Bar 37 Clonmacnoise 73 Ring of Kerry 113 Sonderteil: Christ Church 41 Galway 75 Skellig Michael 115 Whiskey 43 Cong / Cong Abbey 77 Border Collie 118 Hl. Patrick & Hl. Kevin IRLAND-Reise der Pfar- Republik Irland - neben port, der Hl. Berg Irlands, Kerry", einer Hirtenhunde- ren Hain & Statzendorf: Dublin mit dem Book of der Croagh Patrick, Vorführung, Rock of diese führte von 24. März Kells in der Trinity- Kylemore Abbey, die Cashel, Glendalough am bis 1. April auf die "grüne Bücherei, der St. Patricks- Connemara, die Burren, Programm. Dank der guten Insel" Irland. Ohne auch nur Kathedrale und der Guin- Cliffs of Moher, Limerick, Führung, des guten Wetters einmal nass zu werden, be- ness-Brauerei, stand Monas- Muckross House und Friary und einer alles überragen- reiste die 27 Teilnehmer terboice, eine Whiskeybren- (Kloster), eine Räucherlachs den Heiterkeit war es eine umfassende Reisegruppe die nerei, Clonmacnoise, West- -Produktion, der "Ring of sehr gelungene Pfarr-Reise. -

NUI MAYNOOTH MILITARY AVIATION in IRELAND 1921- 1945 By

L.O. 4-1 ^4- NUI MAYNOOTH QllftMll II hiJfiifin Ui Mu*« MILITARY AVIATION IN IRELAND 1921- 1945 By MICHAEL O’MALLEY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller JANUARY 2007 IRISH MILITARY AVIATION 1921 - 1945 This thesis initially sets out to examine the context of the purchase of two aircraft, on the authority of Michael Collins and funded by the second Dail, during the Treaty negotiations of 1921. The subsequent development of civil aviation policy including the regulation of civil aviation, the management of a civil aerodrome and the possible start of a state sponsored civil air service to Britain or elsewhere is also explained. Michael Collins’ leading role in the establishment of a small Military Air Service in 1922 and the role of that service in the early weeks of the Civil War are examined in detail. The modest expansion in the resources and role of the Air Service following Collins’ death is examined in the context of antipathy toward the ex-RAF pilots and the general indifference of the new Army leadership to military aviation. The survival of military aviation - the Army Air Corps - will be examined in the context of the parsimony of Finance, and the administrative traumas of demobilisation, the Anny mutiny and reorganisation processes of 1923/24. The manner in which the Army leadership exercised command over, and directed aviation policy and professional standards affecting career pilots is examined in the contexts of the contrasting preparations for war of the Army and the Government. -

Congressional Record-·Senate. '

2790 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-·SENATE. JUNE 21 · ' 14-±0. By Mr. FULLER: Petition of the American Association 1464. By Mr. SINCLAIR: Petition of Ramsey County (N. of State Highway Officials, favoring Senate bill 1072; to the Dak.) Sunday. School Association, indorsing the Smith-Towner Committee on Roads. · bill; to the Committee on Education. 1441. Also, petition of the American Farm Bureau opposing ;1.465. Also, petition of ·women's Study Club and citizens of a tariff on lumber; to the Committee on Ways and Means. Wildrose, N. Dak., protesting against the pas age of legisla 1442. Also, petition of the Presbyterian Church of Grand tion granting the use of the waters of our national parks Ridge, Ill., favoring a conference of the nations to bring about for commercial purposes; to the Committee on the Public di armament; to the Committee on Foreign Affairs. Lands. 1443. By Mr. GOODYKOONTZ: Resolution of the Martins· 1466. Also, petition of Women's Nonpartisan , League Club; burg (\V. Va.) Chamber of Commerce, urging the passage of No. 18, of Donnybrook, N. Dak., urging disarmament; to the the Dowell road bill ; to the Committee on Roads. Committee on Foreign Affairs. 1.444. By l\1r. GREEN of Iowa: Petition of certain citizens of 1467. Also, petition of Women's Nonpartisan League Club, Iowa favoring recognition of the Irish republic; to the Com No. 72, of Parshall, N. Dak., urging disarmament; to the Com mittee on Foreign Affairs. mittee on Foreign Affairs. H45. By l\Jr. HERSEY: Petition of congregation of Church 1468. By 1\lr. SNYDER: Petition of :Middleville (N. -

Tipperary News Part 6

Clonmel Advertiser. 20-4-1822 We regret having to mention a cruel and barbarous murder, attended with circumstances of great audacity, that has taken place on the borders of Tipperary and Kilkenny. A farmer of the name of Morris, at Killemry, near Nine-Mile-House, having become obnoxious to the public disturbers, received a threatening notice some short time back, he having lately come to reside there. On Wednesday night last a cow of his was driven into the bog, where she perished; on Thursday morning he sent two servants, a male and female, to the bog, the male servant to skin the cow and the female to assist him; but while the woman went for a pail of water, three ruffians came, and each of them discharged their arms at him, and lodged several balls and slugs in his body, and then went off. This occurred about midday. No one dared to interfere, either for the prevention of this crime, or to follow in pursuit of the murderers. The sufferer was quite a youth, and had committed no offence, even against the banditti, but that of doing his master’s business. Clonmel Advertiser 24-8-1835 Last Saturday, being the fair day at Carrick-on-Suir, and also a holiday in the Roman Catholic Church, an immense assemblage of the peasantry poured into the town at an early hour from all directions of the surrounding country. The show of cattle was was by no means inferior-but the only disposable commodity , for which a brisk demand appeared evidently conspicuous, was for Feehans brown stout. -

Crystal Reports

Bonneagar Iompair Éireann Transport Infrastructure Ireland 2020 National Roads Allocations Galway County Council Total of All Allocations: €28,848,266 Improvement National Primary Route Name Allocation 2020 HD15 and HD17 Minor Works 17 N17GY_098 Claretuam, Tuam 5,000 Total National Primary - HD15 and HD17 Minor Works: €5,000 Major Scheme 6 Galway City By-Pass 2,000,000 Total National Primary - Major Scheme: €2,000,000 Minor Works 17 N17 Milltown to Gortnagunnad Realignment (Minor 2016) 600,000 Total National Primary - Minor Works: €600,000 National Secondary Route Name Allocation 2020 HD15 and HD17 Minor Works 59 N59GY_295 Kentfield 100,000 63 N63GY RSI Implementation 100,000 65 N65GY RSI Implementation 50,000 67 N67GY RSI Implementation 50,000 83 N83GY RSI Implementation 50,000 83 N83GY_010 Carrowmunnigh Road Widening 650,000 84 N84GY RSI Implementation 50,000 Total National Secondary - HD15 and HD17 Minor Works: €1,050,000 Major Scheme 59 Clifden to Oughterard 1,000,000 59 Moycullen Bypass 1,000,000 Total National Secondary - Major Scheme: €2,000,000 Minor Works 59 N59 Maam Cross to Bunnakill 10,000,000 59 N59 West of Letterfrack Widening (Minor 2016) 1,300,000 63 N63 Abbeyknockmoy to Annagh (Part of Gort/Tuam Residual Network) 600,000 63 N63 Liss to Abbey Realignment (Minor 2016) 250,000 65 N65 Kilmeen Cross 50,000 67 Ballinderreen to Kinvara Realignment Phase 2 4,000,000 84 Luimnagh Realignment Scheme 50,000 84 N84 Galway to Curraghmore 50,000 Total National Secondary - Minor Works: €16,300,000 Pavement HD28 NS Pavement Renewals 2020 -

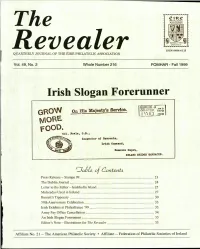

Irish Slogan Forerunner

The Revea er ISSN 0484-6125 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE EIRE PHILATELIC ASSOCIATION VoL 49, No. 2 Whole Number 216 FOMHAR - Fall 1999 Irish Slogan Forerunner GROW On His ]lajesty'sBervlce. MORE fOOD. Col. Powle, O.B., Inapector ot .Bemount., Irllh COJIIIland, Remount. Depot., ISLAlttl BRIDGE BARRACKS • . ClafrtE- of {!ontE-nt~ Press Release - Stampa 99 .. .. ... .. ... .. ... ... .. ...... ............ .. .. .. .... .. .. .. .. .... .. .... .. .. ........ .. 23 The Dublin Journal .... .. .... .. .. .. .. .... .... .. ..... .. .. .. ...... ..... .. .. ... .. ... .......... .. .... .... .. .. .. .. .. .. 24 Letter to the Editor - Inishbofin Island ........................ .. .... .. .. .............. .. ........ .... 25 Mulreadys Used in Ireland .. .......... .. .... ............... :........ .............. .. ...... .. .. .. .. .. .... .. .. 27 BasseU's Tipperary ....... ..... ..... ... ... ... ..... ......... ... .... .. .. ...... .... .... .... .... .... .... ............. 30 50th Anniversary Celebration ... .. .. .. .. ...... .. .. .. .. .... ..... .. .. ............ .. ........ .. ........... .. .. 33 Irish Exhibits at Philexfrance '99 .. .... .. ..... .. ........ .. ... .. ...... .. .... ........ .. .. .... .... .. .. ...... 33 Army Pay Office Cancellation .. .. ...... .. .. .......... .. .. .. .. ...... .. .. .......... .. .. ........ .. .. ........ 34 An Irish Slogan Forerunner .. .. .. .... .. .. .... ........ .. .. .. .. .... .. .. .. ..... .............. .. ............. .. 35 Editor's Note - Illustrations for The Revealer .. ..... -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

A Seed Is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA from the Earliest Times, The

A Seed is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA From the earliest times, the people of Ireland, as of other countries throughout the known world, played ball games'. Games played with a ball and stick can be traced back to pre-Christian times in Greece, Egypt and other countries. In Irish legend, there is a reference to a hurling game as early as the second century B.C., while the Brehon laws of the preChristian era contained a number of provisions relating to hurling. In the Tales of the Red Branch, which cover the period around the time of the birth of Christ, one of the best-known stories is that of the young Setanta, who on his way from his home in Cooley in County Louth to the palace of his uncle, King Conor Mac Nessa, at Eamhain Macha in Armagh, practised with a bronze hurley and a silver ball. On arrival at the palace, he joined the one hundred and fifty boys of noble blood who were being trained there and outhurled them all single-handed. He got his name, Cuchulainn, when he killed the great hound of Culann, which guarded the palace, by driving his hurling ball through the hound's open mouth. From the time of Cuchulainn right up to the end of the eighteenth century hurling flourished throughout the country in spite of attempts made through the Statutes of Kilkenny (1367), the Statute of Galway (1527) and the Sunday Observance Act (1695) to suppress it. Particularly in Munster and some counties of Leinster, it remained strong in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

Dáil Éireann Pursuant to Section 6 of the Above Mentioned Acts in Respect of the Registration Period 1 January, 2002 to 31 December, 2002

1 NA hACHTANNA UM EITIC IN OIFIGÍ POIBLÍ, 1995 AGUS 2001 ETHICS IN PUBLIC OFFICE ACTS, 1995 AND 2001 CLÁR LEASANNA CHOMHALTAÍ DHÁIL ÉIREANN DE BHUN ALT 6 DE NA hACHTANNA THUASLUAITE MAIDIR LEIS AN TRÉIMSHE CHLÁRÚCHÁIN 1 EANÁIR, 2002 GO DTÍ 31 NOLLAIG, 2002. REGISTER OF INTERESTS OF MEMBERS OF DÁIL ÉIREANN PURSUANT TO SECTION 6 OF THE ABOVE MENTIONED ACTS IN RESPECT OF THE REGISTRATION PERIOD 1 JANUARY, 2002 TO 31 DECEMBER, 2002. 2 AHERN, Bertie (Dublin Central) 1. Occupational Income .............. Nil 2. Shares ...................................... Nil 3. Directorships ........................... Nil 4. Land ........................................ Nil 5. Gifts......................................... (1) Honorary membership of Grange Golf Club for the year 2002: The Captain and Committee of Grange Golf Club, Rathfarnham, Dublin 16; (2) Honorary membership of Elm Park Golf Club for the year 2002: The Captain and Committee of Elm Park Golf and Sports Club Ltd., Donnybrook, Dublin 4; (3) Courtesy of Portmarnock Golf Club Course and Club House for the year 2002: The Captain and Committee of Portmarnock Golf Club, County Dublin. Other Information Provided: (1), (2) & (3) I will not realise any material benefit from these as I do not play golf. 6. Property and Service ............... See Donation Statement for 2002 under the Electoral Acts, 1997-2002. 7. Travel Facilities ...................... Return flights to Cardiff for European Rugby Cup Final (Munster v Leicester) on 25/5/02 on private aircraft; DCD Limited., St. Helen's Wood, Booterstown, Co. Dublin. Other Information Provided: The sum of €1480 has been refunded to the donor, in accordance with Government guidelines (Section 15(4) of 1995 Act). 8. -

FORUM Connemara CLG End of Year Report 2018

FORUM Connemara CLG End of Year Report 2018 1 FORUM CONNEMARA CLG END OF YEAR REPORT January –December 2018. Introduction From January December 2018, Forum staff implemented actions under a number of programmes; The Rural Development Programme (Leader), The Adolescent Support Programme, the Rural Recreation Programme (RRP), the Rural Social Scheme, and Labour Activation Programmes Tus, Job Initiative, and Community Employment. There were difficulties in filling Tus places and in April the Department proposed a cutback to our allocation from 80 to 40 places. Forum meet with the Department in October .The Department confirmed our allocation of 40 places on Tus and 36 on RSS .The company lost two TUS supervisors but gained an additional supervisor for the RSS programme. Forum were allocated an additional 12 places on the RSS programme. These places are filling slowly, There are currently 31 places filled with 5 places remaining to be filled .. There will be a further review of places on both schemes scheme at the end of April 2019. During the year various staff gave comprehensive presentations on their work to the Board of Directors. This included work undertaken by the Rural Recreation Officer and the Adolescent Support Coordinator. The Adolescent Support Programme had a very successful 20th birthday celebration in May and there was also a presentation of the programmes activities to the GRETB Board who part fund the programme. The company’s finances are in a healthy state as at the end of December . Minister Ring’s Mediator/Facilitator: Representatives from Forum meet with Tom Barry facilitator on Wednesday 28th March 2018. -

CSG Bibliog 24

CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 29 (2016) By Dr Gillian Scott with the assistance of Dr John R. Kenyon Introduction Hello and welcome to the latest edition of the CSG annual bibliography, this year containing over 150 references to keep us all busy. I must apologise for the delay in getting the bibliography to members. This volume covers publications up to mid- August of this year and is for the most part written as if to be published last year. Next year’s bibliography (No.30 2017) is already up and running. I seem to have come across several papers this year that could be viewed as on the periphery of our area of interest. For example the papers in the latest Ulster Journal of Archaeology on the forts of the Nine Years War, the various papers in the special edition of Architectural Heritage and Eric Johnson’s paper on moated sites in Medieval Archaeology. I have listed most of these even if inclusion stretches the definition of ‘Castle’ somewhat. It’s a hard thing to define anyway and I’m sure most of you will be interested in these papers. I apologise if you find my decisions regarding inclusion and non-inclusion a bit haphazard, particularly when it comes to the 17th century and so-called ‘Palace’ and ‘Fort’ sites. If these are your particular area of interest you might think that I have missed some items. If so, do let me know. In a similar vein I was contacted this year by Bruce Coplestone-Crow regarding several of his papers over the last few years that haven’t been included in the bibliography.